In Memory of Ernie Tate (1934-2021): A Life of Revolutionary Activism

The socialist movement lost an outstanding educator and organizer with the passing of Ernest (Ernie) Tate in Toronto on 5 February. An outstanding partisan of global anti-imperialist solidarity, Ernie also contributed, with his partner Jess MacKenzie, to building revolutionary Marxist groups and to promoting socialist unity in Canada and Britain.

Raised in an impoverished working-class community in Belfast, Ernie left school at age 14, taking a job at Belfast Mills as apprentice machine attendant. An avid reader and a rebel at heart, Ernie sympathized – unusually, given his Protestant background – with the Irish republican movement.

During a youthful jaunt through France in 1954, Ernie was deeply impressed by the mass solidarity actions celebrating the victory of Vietnamese freedom fighters in Dien Bien Phu. The following year, Ernie took the path of so many of his countrymen and emigrated, settling in Toronto.

Soon after his arrival in 1955, Ernie dropped by the Toronto Labour Bookstore, a small socialist organizing centre which he had seen mentioned in an Irish newspaper. Entering the store, he asked for the novel King Jesus by Robert Graves. Fortunately, the proprietor Ross Dowson turned out to be a socialist with a similarly broad intellectual scope. Dowson had a lot to say about Graves, a British radical poet and historical novelist but soon steered Ernie to a display of socialist newspapers and pamphlets in the back of the store.

Ernie was pleased to see the display’s pro-Soviet orientation but also noted many writings on display by Leon Trotsky, the historic antagonist of the Stalin regime in the Soviet Union. A long conversation ensued. Pro-Soviet currents were then in turmoil as a result of revelations regarding the crimes of Stalin and his regime. Dowson advocated responding through discussion and collaboration among diverse socialist currents, a process that he called “regroupment.” Ernie embraced this goal and pursued it diligently throughout 65 years of activism.

The bookstore, Ernie discovered, doubled as headquarters of a group of about fifteen socialist activists, which that year took the name Socialist Education League (SEL). Dowson introduced Ernie to other members of the group, and Ernie soon joined its ranks.

‘Awakening from a Long Sleep’

“For me as a young person,” Ernie later recalled, “joining a socialist organization, no matter how small, was like at last awakening from a long sleep. Vague ideas and feelings I had about society that I had come to by myself now began to be integrated into a systematic historical and political outlook… Above all, it gave a coherent expression to what had been a sense of injustice that I had until then been unable to articulate… To this day I have always separated those two phases of my adult life: the period before and after joining the group.”1

Ernie found his feet in the SEL; socialist activism came to him naturally. The prospect of socialist regroupment gave the Toronto group prospects far beyond its slender numbers and soon involved Ernie in a complex and important assignment. In 1957, the SEL sent Ernie to New York to help carry out a fusion of youthful socialist forces with the Socialist Workers Party, the US sister organization of the SEL. A year later, these forces joined in creating the Young Socialist Alliance, which was to play a prominent and creative role in the youth upsurge of the 1960s.

The SEL and SWP formed part, Ernie learned, of a global association of revolutionary Marxist groups called the Fourth International, which was distinguished by its alignment with Leon Trotsky in his criticisms of Stalinism and strategy for world revolution.

Mission accomplished, Ernie returned to Toronto with a partner, the New York socialist Hannah Lerner. Hannah took part in Toronto socialist activity for a time but returned to New York two years later. Meanwhile, Ernie plunged into Toronto union work and joined preparations to launch a labour-based political party – today’s NDP. His influence was felt in every work area. In the SEL, Ernie was quick to state his views and defend them, even when they ran against the grain of his consensus-oriented organization. Nonetheless, despite occasional discord, Ernie long maintained a fruitful collaboration with Ross Dowson and other SEL comrades.

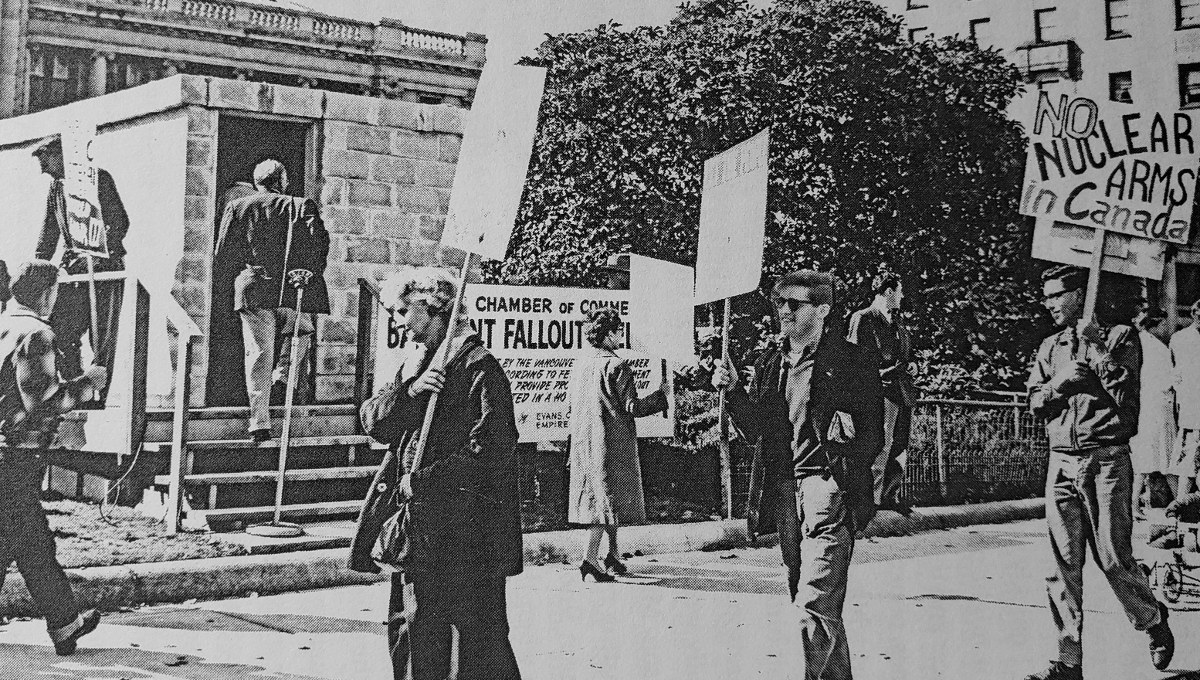

Vancouver Years

In 1962, Ernie trekked west with an SEL organizing tour to Vancouver, where he joined his partner Ruth Robertson. They had a son, Michael, in 1963; Ruth returned to Toronto the following year.

While in Vancouver, Ernie headed the local branch of the SEL, which was now known as the League for Socialist Action (LSA). He worked with some success to bring the Vancouver and Toronto LSA branches into more harmonious alignment. During these years, the LSA branches began to attract many promising student activists. With his charm, energy, generosity of spirit, and wide intellectual perspectives, Ernie won an extensive range of such youthful contacts as friends and recruited many of them to LSA membership.

Ernie had an instinctive feel for and capacity to learn from the nascent social movements in which the younger comrades were active. He was unique in his capacity to span the two generations and social milieus, and thus to facilitate their ultimate fusion into a single team.

Ernie was deeply engaged in the formation of the New Democratic Party’s youth wing and in consolidating union support for the new labour-based party. But even more than the NDP, it was the Cuban revolution that dominated the thinking of LSA members in the early 1960s. Welcoming the revolution with joy, Ernie joined in building the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, a broadly based alliance to help defend Cuba against US aggression and to convey Cuba’s message to a broad public in Canada.

Fourth International Reunification

Revolutionary socialists worldwide rallied to defend revolutionary Cuba, and this process promoted a wide-ranging rapprochement among forces in the Fourth International that had been separated by a factional breach during the 1950s. Among the first to perceive this process, Ernie was impatient with those who insisted on doctrinal differences as cause to resist unity.

“There are differences in the International,” Ernie wrote in a November 1961 letter. “But they are not of interest to the large part of our readers and appear esoteric. They will be resolved not by paper agreements but around issues and struggles. We should look at who is coming toward us and not be overly concerned with maintaining our political virginity.”2

Most of the Fourth International’s scattered sections reunified in 1963, and the small but ambitious world movement began to put on weight and muscle and gain in influence. The International had a major weak spot, however: it lacked an effective section in Britain.

As part of its commitment to Fourth International reunification, the LSA’s Canadian section, maintained a full-time representative in London, Alan Harris, aided by his wife Connie. Alan worked for several years with the International’s supporters in Britain and was now nearing the end of his assignment. Ernie, with his Northern Irish background and strong socialist credentials, was the logical replacement. In 1965, Ernie moved to London on a staff assignment from the LSA to help assure the success of the Fourth International’s reunification, particularly through establishing a viable national section in Britain.

Assignment in London 1965-69

Once in London, Ernie set up Pioneer Books to continue the distribution, started by Alan and Connie Harris, of socialist books and pamphlets, mostly published by the SWP. Ernie arranged to rent space at 8 Toynbee Street, which became a centre for Fourth International supporters. He collaborated with a group of the International’s supporters in Nottingham called the International Group (IG). Early in 1966, Pat Jordan, editor of the IG’s publication The Week moved to London, and a year later the IG members launched the International Marxist Group (IMG) as the British Section of the Fourth International.

In late 1966, Ernie formed an enduring partnership with Jess MacKenzie, a Scottish socialist, and the couple were henceforth regarded by friends and comrades alike as an effective political team.

The Pioneer Book Service flourished under Ernie’s care, providing Marxist books to a growing socialist milieu at a time when writings by Lenin, Trotsky, or Ernest Mandel were not to be found in mainstream bookshops. Ernie and Jess worked on the IMG’s political projects, and Jess was, for a time, organizer of the IMG’s small London branch.

Let’s let Phil Hearse, Jess and Ernie’s close comrade during their London years, tell about their work in Britain.

Phil Hearse on the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign

“At the 1965 World Congress of the Fourth International asked its sections to turn toward solidarity with the Vietnamese struggle. The IMG was instrumental in forming the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign (VSC), in which Ernie was a leading light. Through this, Ernie became known to wider sections of the Left, and the campaign enabled him to put his engaging personality to good political use. He and Jess embodied some of the best features of the North American Trotskyist tradition at that time – calm and reasoned judgement, together with organizational seriousness. Ernie combined that with boundless good humour, a dry wit and a winning smile.

“To build the VSC meant working with some of the well-known left wingers who supported the campaign, like engineering union executive member Ernie Roberts, Marxist academic Ralph Miliband, members of the New Left Review team like Quintin Hoare and Perry Anderson – and, crucially, Tariq Ali, former President of the Oxford University student union, a highly effective speaker and VSC’s best known figure.

“VSC revived the idea of solidarity, unconditional support for the oppressed in struggle, resuming in some ways the mood of the Left during the Spanish Civil War.

“Ernie, Jess, and Pat Jordan were all involved in organizing the VSC’s first major demonstration in October 1967, which finished with clashes outside the old American Embassy in Grosvenor Square. The National Liberation Front’s spectacular Tet Offensive at the end of January 1968 fuelled the next major demonstration in March of that year, which finished with even more violent clashes with the police defending the embassy – and the giant demonstration of 200,000 that followed in October.

“Ernie became centrally involved in a linked major initiative, the Bertrand Russell War Crimes Tribunal, which mobilised well-known figures to weigh the evidence, of which there were ample quantities, of American war crimes in Vietnam. Ernie worked with Ralph Schoenman, Bertrand Russell’s key assistant, and his work on the Tribunal brought him into contact with such figures as Jean-Paul Sartre, French writer KS Karol, Simone de Beauvoir, Scottish miners leader Lawrence Daly, and Isaac Deutscher.”

Back to Canada

Ernie and Jess had a significant impact on the political culture of revolutionary Marxism in Britain. Hearse tells us, “It was through comrades like Ernie that the far left was able to raise its sights to a new conception of internationalism and a deeper understanding of gender and racial oppression.”

Despite all these achievements, however, Jess and Ernie were never able to find adequate financial support for their British venture. Promised payments from the LSA in Canada were infrequent and inadequate. Family and personal responsibilities increasingly pressed in on them. So it was, Hearse explains, that in 1969 “they decided to go back to Canada, where they could get well-paid jobs, meet their commitments, and prepare for the future.”

Yet despite his immense reputation and record of achievement in the socialist movement, Ernie was not integrated into the LSA’s leadership in Toronto. There was a fractious debate over a terminological issue: Ernie considered it premature to affirm that the LSA was the “nucleus” of the future mass revolutionary party. Neither the terminological issue and the breach on the leadership level were resolved.

New Perspectives in Toronto

Nonetheless, Ernie and Jess continued their political and trade union work as LSA members, while setting about to rebuild their lives on a firmer foundation. Ernie upgraded his job qualifications through three years’ study at Ryerson Polytechnic Institute, winning two prizes for English writing assignments. He took engineering jobs at several industrial plants, including at Toronto Hydro from 1977 until his retirement in 1995. During his final years on the job, he led the successful campaign of the Hydro unionists against privatization in the 1990s.

After some years of preparations, Ernie and Jess acquired a house in Toronto, built a summer home on Ontario’s Bruce Peninsula, and devoted fond attention to gardening and to their forest getaway. It was a happy outcome for them both, which they shared generously through hospitality to friends, neighbours, and comrades.

Meanwhile, Ernie and Jess remained actively involved in the LSA. On three occasions, Ernie stepped forward to provide decisive help.

The first occasion occurred in the summer of 1972 when Ross Dowson resigned from his leadership post in the LSA. By this time, the LSA had several hundred members in more than a dozen branches from coast to coast. The LSA was fraught with internal tensions. Ernie stepped forward to advise and assist the team of younger, less experienced leaders in holding the League together and organizing a thorough discussion of the disputed issues.

The second occasion arose in 1977. The LSA joined with three other Fourth Internationalist groups in Canada in undertaking a complex fusion. Ernie played a central role in the joint leadership discussions, working to encourage the mutual confidence needed to carry through the merger. The fusion created a new organization, Revolutionary Workers League/Ligue Ouvrière Révolutionnaire (RWL/LOR), which briefly embraced close to 500 members – the numerical highpoint of the Fourth International’s history in Canada.

Two years later, Ernie helped the RWL carry out a campaign to vastly increase its presence in industrial trade unions, holding weekly classes to instruct members in elementary factory skills. “I thought it was a great thing,” he later commented, but the effort soon swerved sharply in an extremist and sectarian direction, colonizing workplaces where he saw little or no scope for union work. “Pure, unadulterated nonsense,” he later commented. “The ‘Turn to Industry’ destroyed the movement.” Ernie resigned from the RWL in the 1980s.

New Directions

Meanwhile, Ernie was reaching out in many new directions.

- He rallied to the protest movements against US-led wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. “His insights about his own anti-war experiences decades earlier were invaluable,” recalls these movements’ central organizer, James Clark.

- Ernie and Jess were active supporters of the Fight for $15 and Fairness minimum wage campaign, joining with hundreds to celebrate Bill 148 (later overruled) that legislated this reform.

- Ernie contributed detailed written testimony to the Undercover Policing Inquiry, an inquiry launched in 2015 into police spying in England and Wales since 1968.

- In 2019, Ernie was one of a handful of speakers from outside Latin America to speak at an international conference on Leon Trotsky and Trotskyism in Havana, Cuba.

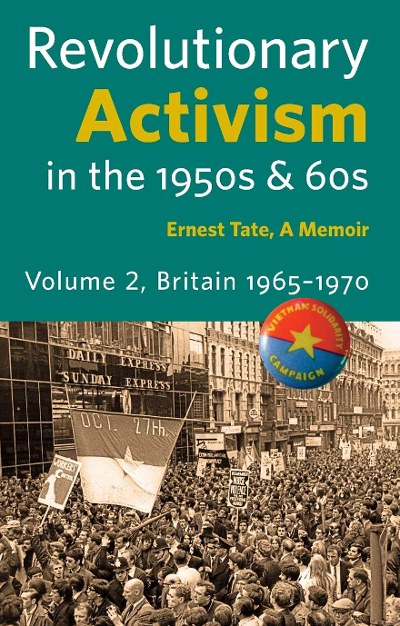

- And throughout all this, Ernie worked away on preparation of his uniquely insightful two-volume memoir, Revolutionary Activism in the 1950s and 60s. Published in 2014 by Resistance Books, the memoir provides a searching portrait of a revolutionary working-class current in Canada and Britain during its historic highpoint of militancy.

- He took part in successive socialist regroupment ventures: the New Politics Initiative, Rebuilding the Left, the Greater Toronto Workers Assembly, and Socialist Project.

Alongside his continuing activism, Ernie joined with Jess in writing a succession of thorough, probing, and thoughtful papers on major issues facing world socialism, such as the fall of the Soviet Union, epochal changes in China, the rise of the Scottish Socialist Party, and the Zapatista movement in Mexico. [Articles by Ernie Tate published by The Bullet.]

Steve Maher of Socialist Project recalls:

“Ernie came to every meeting, all the talks, taking diligent notes. He’d always speak, asking probing questions and offering rich insight – a highlight of the evening.

“Ernie always had a bright smile. Open to questions, he related to others with warmth. When he encountered disagreement, he did not shy back; he would always keep the discussion open.

“What drove him? He was just so committed to the cause of the working class.”

After his 65 years of fruitful socialist engagement and comradeship, Ernie leaves to us a wealth of gifts: the memory of his passion, his sincerity, the warmth of his smile, his welcoming inclusivity, and a rich legacy of ideas and achievements whose influence will be long felt in the socialist movement.

With thanks for editing assistance to Phil Hearse, Richard Fidler, Suzanne Weiss, and Jess MacKenzie.

Reviews of Ernie Tate’s Revolutionary Activism in the 1950s and 60s

- “Learning from our History,” by Richard Fidler.

- “Breaking a Path for the Sixties Radicalization,” by John Riddell.

- “A Tate Gallery for the New Left: Portraits, Landscapes, and Abstracts in Revolutionary Activism of the 1950s and 1960s,” by Bryan Palmer.

- Revolutionary Activism book launch (LeftStreamed, June 11 2014).

Endnotes

- Ernest Tate, Revolutionary Activism in the 1950s and 60s, London: Resistance Books, 2014, vol. 1, pp 30-31.

- Letter to John Riddell, 11 November 1961.