What Do Mine Tailings Dam Disasters Teach Us?

Brazilian mining activists invited Judith Marshall to participate in their November 5th commemorations of the anniversary of the tailings dam collapse at the Vale/BHP iron mine in Mariana, Brazil. Marshall was a founding member of the International Network of People Affected by Vale (AV) formed in 2010 while she worked in the Global Affairs Department of the Steelworkers Union. After her retirement, Marshall became an Associate of CERLAC (Centre for Latin American and Caribbean Studies) at York University where she has continued her collaboration with AV, including comparative studies of the Mariana spill with the tailings dam collapse at Mt. Polley in British Columbia. Below is her message to the event.

Further political and ecological analysis of tailings dam spills can be found here as part of the corporate mapping project.

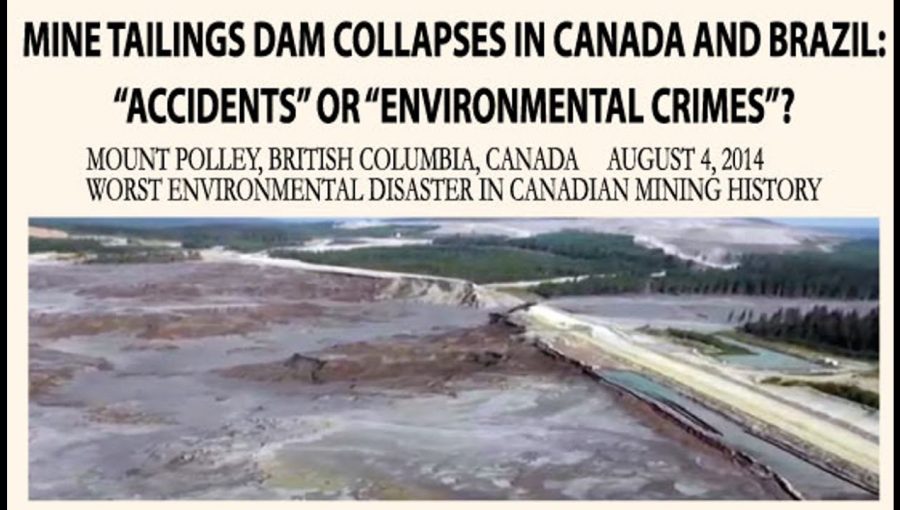

So here we are, on November 5th, commemorating the anniversary of the Mariana tailings dam collapse and dealing with the consequences of the three biggest mining catastrophes in the Americas. Just 14 months before the Mariana crime, the tailings pond collapsed at Mt. Polley, a copper/gold mine in British Columbia province, creating the largest tailings dam collapse in Canadian history. Less than four years after Mariana, Vale’s Brumadinho tailings dam collapsed, creating not only damages to nearby ecosystems but also triggering the worst industrial tragedy in Brazilian history, burying 272 people in toxic muck in a matter of minutes. What are the lessons these collapses can teach?

First, we need to learn that our governments, both in Canada and Brazil, are faithful adherents to the neoliberal world order. Our governments have adopted the mining industry narrative that a mining investment brings jobs and economic growth, that getting a country’s resources onto global markets is the highest good. Our government leaders basically understand their role to be promotion of more investments in mining rather than regulation of mining for the public good and environmental sustainability. They accept the mining industry’s claims of expertise and step back to let mining self-regulate. Our governments give mining companies tax breaks and hydro subsidies.

Mining’s Gigantic Footprint: “Environmental Dispossession”

If we hadn’t already learned how much our governments had become advocates of the mining industry before the tailings dam tragedies, we certainly learned afterwards. We watched as the companies enjoyed immunity, with little or no punishment. Sadly, we realized that we could not depend on our governments for defence of people affected by mining or defence of the environment. So, lesson one is that we are on our own, as governments basically side with the mining industry. And that has meant a huge challenge for civil society to step up and fill advocacy and service roles that should have been being filled by our governments. Congratulation to you in Brazil, in social movements like MAB, network of organization like AV, churches and universities for the creative ways you have responded.

Lesson two from the tailings dam collapses is the urgent need to broaden our understanding of mining’s footprint. We all know that a mining license for underground or open-pit extraction often means dispossessing people of their land and resettling them elsewhere. Are we sufficiently aware of the scope of a mining operation and its gigantic footprint on the surrounding ecology? The concept of “environmental dispossession” needs to enter our vocabulary. We need to understand how a mine sets in motion multiple processes of dispossession. Traditional and Aboriginal communities are faced with systematic reduction in the resources like land, forests, water ways, flora, and fauna on which they have historically depended for farming, hunting, gathering, trapping, and fishing. What diversity of traditional occupations is being suppressed as mining comes to dominate?

The footprint of a mine includes roads, rails, pipelines, and ships to get ore to global markets. It includes massive demands for water for the extractive process, and often, massive pollution by dumping water made toxic through these same processes of extraction.

Tailings dams are already a huge component of a mine’s foot print when intact, but when they collapse, the full scope of that footprint becomes visible. Hundreds of people along 650 km of the Rio Doce river system never understood themselves as “affected by mining” until they had to flee from Mariana’s toxic tsunami making its way to the Atlantic, destroying their land, their homes, and their livelihoods. And then they had to fight to be recognized as “affected” and eligible for compensation.

In Canada, the communities affected by the Mt. Polley collapse are almost entirely Indigenous, with a history of colonialism and genocide and contemporary struggles to defend their rights. A Health Impact Assessment carried out after the spill identified 46 First Nations communities in the area of the Mt. Polley spill, sprinkled throughout the Fraser River Basin, some as far as 200 km from the mine site. Environmental dispossession was strongly in evidence as mining projects like Mt. Polley affected their land use and water quality making it harder for Indigenous communities to carry out traditional occupations like hunting, gathering, and fishing. Around Mt. Polley, the Indigenous communities all live with salmon fishing as central to their lives, contributing in a major way to their nutritional needs but also the central feature of their spiritual beliefs and religious rites as caretakers of mother earth. The Mt. Polley catastrophe created major concerns about the health of the fish, with many communities putting an immediate halt to fish consumption. Health of the nearby lakes and rivers themselves is another major concern, as well as long-term health of the salmon.

Neither mining company nor government has been attentive to the impacts on these communities or their rights to compensation. Civil society organizations in Canada could be playing larger advocacy and servicing roles to make visible the grave injustice being perpetrated in these dispersed communities.

A Global Industry Driven Solely by Profit Margins

A third lesson to be learned is that the mining industry operates globally and is driven by profit margins above all else. For a big mining company like Vale, local and even national concerns are peripheral, issues to be managed rather than rights and relationships to be respected. I felt proud to still be part of the International Articulation of People Affected by Vale when I got news of the lobbying trip to Europe last year, going global in the fight against Vale, tackling the world of supply chains and global governance. The stop in Switzerland shone a light on tax evasion. The Swiss government allows Vale Switzerland to be, at least on paper, the main importer of the massive exports of iron ore from Carajas. Vale Switzerland buys from Vale Brazil at below-market prices. Vale Switzerland then turns around and re-sells this ore to China at full market price, pocketing the difference. This cheats the Brazilian government of export revenue it could have been using on important social programmes in Brazil. The stop in Switzerland also included participation in the UN process of drafting a new policy of human rights and transnational corporations. Tighter measures on the tax loopholes made available to Vale by the Swiss government are a big component of the new policy.

The Brazilian lobbyists then went to Bonn where they joined with Europe-based church and human rights organization in meetings with the German parliament. They raised issues of German government responsibility for German companies operating internationally like TUV Süd. Through its Brazilian subsidiary, TUV Süd had issued a stability declaration for Brumadinho just 4 months before it collapsed.

Best wishes for strength and courage and creativity as you carry on this fight to end corporate impunity and strengthen the capacity of people affected by mining to defend their rights. We should measure what we are doing not so much by what we are able to achieve but by what we become when we work together to care for each other and care for planet earth. A luta continua. •

| Tailings Dam Collapses in the Americas | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ownership | Imperial Metals Corporation | Vale/BHP 50/50 | Vale |

| Location | Williams Lake, BC | Mariana, Brazil | Brumadinho, Brazil |

| Products | Copper/gold | Iron | Iron |

| Operations | Open pit mine, mill, tailings dam, truck transport to port in Vancouver | 2 open pit mines, 3 processing plans, 4 pellet plants, 3 mineral pipelines, 3 tailings dams, port in Vitoria | Open pit mine, non-operational since 2015, railway lines, upstream tailings dam above admin offices and cafeteria |

| Tailings Dam Collapse | August 4, 2014 | November 5, 2015 | January 25, 2019 |

| Volume of Spill | 25 million cubic meters | 32 million cubic meters | 12 million cubic meters |

| Environmental Impact | Surrounding eco-systems damaged, salmon spawning areas destroyed | Toxic tsunami through 600 km Rio Doce river system to Atlantic Ocean destroying land, property and livelihood along route | Eco-system damages throughout the Paraopeba River system threatening urban water supply and down-river hydro-electric dams |

| Social Impact | 0 fatalities, environmental dispossession affecting more than 50 Indigenous communities in Fraser River basin | 19 fatalities in communities next to tailings dam, loss of livelihoods throughout Rio Doce basin, home to 3.2 million people | 272 fatalities, mainly Vale employees including engineers, doctors, etc. Also loss of livelihoods for affected communities on the Paraooeba River |

| Source: Compiled by Judith Marshall. | |||