The City Dispossessed of Its Commons

The city as a way of dwelling in the world has not always existed – quite the contrary. In fact, most of the long history of our species has taken place outside of any urban setting. The global triumph of the city in our time, paradoxically, hides its disappearance as a common space of exchange and relationships inhabited by those who freely, and autonomously, appropriate it. The empty urban landscapes of the current crisis suggest to our gaze, beyond an apocalyptic tone fueled by fear, the expectation of a “return to normal.”

Taking these urban landscapes of emptiness as a starting point, it is possible to show that their exceptional character screens the multiple links that they share with the features of urbanization achieved since the middle of the 20th century. These images of stopped cities, of deserted and silent streets, thus form part of a long-term process instead of being exceptions in urban history. To make use of the current crisis as an analytical lens to highlight not its discontinuities but, rather, its continuities with the geography and experience of the city of our time: such is the gamble of the following reflections on our urban condition today, located at the intersection of geography, history and political theory.1

Dispossession

Our experience of the city today is made of not only confinement but also of dispossession. The city as a commons, that is to say as a public space comprising exchanges, relationships and resources freely appropriated by the inhabitants of the city, has practically disappeared in the current living experience.2 This ongoing dispossession has several features that are all corollaries of the geography of the city as it emerges from the second half of the 20th century.

The current pandemic crisis, therefore, seems to have brought to their climax all the dynamics affecting the urban world in the last half-century, leading to the birth of a new centrality that one would be tempted to call “post-urban”: the home, the private residence of each inhabitant. The current confinement of half the world’s population – early April – materializes this separate existence in the same city. In this new urban experience, the common space no longer exists: mobility and flows are reduced to an absolute minimum.

The aesthetic experience of the city – its squares, its stations, its metro stations, its emblematic monuments, its public places – is mainly achieved through the mediation of screen-images. Relationships with other residents are avoided. The social relationships that structured each street, each neighborhood of the city, vanish, making the city and its buildings an empty shell, without any content, without relationships.

This absent city, made of deserted streets deserted by its inhabitants, recalls the public emptiness of the streets of Paris following the terrorist attacks of 2015. In the days following these attacks, at the time of collective stupor, the city seemed, like today, to literally hide under our feet, leaving only the private space of the apartment or house as a way of inhabiting the world. This constrained confinement, through fear and the landscapes that this produced in the city, has come back to our consciousness today.

The ‘de-confinement’ will take place sometime in the foreseeable future and we will undoubtedly return to a certain “normality” that we knew before mid-March. But the feeling of dispossession and loss of a commons that we tragically feel today is perhaps here to stay because the city-commons has been destroyed everywhere, even for as long as half a century. It’s this feeling of dispossession that resonates within us and, perhaps, makes us love the melancholy of the Rolling Stones in Living In A Ghost Town.

The post-urban centrality of the private space of the home that we live in today seems to have a bright future. Even before the current crisis, telework was a remote work arrangement that was on the rise. It is likely to become a new managerial standard to intensify the exploitation of workers in the “cognitive phase of capitalism,” using the digital panopticon.3

Environmental crises, such as the fine particle pollution peaks in winter that Western Europe has experienced recently, as well as the increasing violence of world disorder, including that of terrorism, are likely to make us go through other confinements in the time to come. The experience of the city that we undergo today, characterized by the absence of the commons, therefore, seems less exceptional than it might seem to us at first glance. It is likely to be long-term since the city-commons is threatened from all sides and since the crises accumulate and succeed each other without respite. Marx noted in The Communist Manifesto (1848) that the capitalist mode of production “cannot exist without constantly revolutionizing (…) the whole relations of society.” Among other things, this means that the crises in the world are by no means an anomaly. On the contrary, they are the norm, as Michael Hardt and Toni Negri underline in Empire, where the capitalist world-system “is defined by the crisis.”4 The repetition of crises hence feeds the disappearance of the urban commons.

This collective dispossession, however, comes from afar. It is part of the logic of urban geography of the last half-century.

Break-up

This strange daily life that we live confined in our cities today resonates with the slow corrosion of urban commons around the world. These cities look like a shadow of themselves – without monuments, without common spaces, without multifunctional central points of connection and gathering, without the diversity of the multitude. The crisis bring us all back, in unforeseen ways, to our strange daily life in our confined cities.

Henri Lefebvre is one of the first to be interested in the destructive processes threatening the urban commons. While large complexes were built in the suburbs in the 1950s and 1960s in Europe, cities experienced a process of sprawl that has continued up to now. Beyond the suburbs, vast suburban areas and housing estates embodied the bourgeois ideal of a single-family home and a nation of owners. Individual houses, cars, mass consumption and functional segregation thus became specific characteristics of a new way of dwelling in the city, which was reflected not only in the sprawl of the city but also by the break-up of the city-commons.

This longue durée process is still at work and combines with other powerful processes. Metropolitan urban areas polarizing and encompassing entire regions are echoed by the metropolization of urban networks and the intensification of flows criss-crossing the city. These processes also contribute to the destruction of the urban commons. In the new metropolis paradigm, flows and mobilities become the new political horizon of city government: to capture them, channel them, sort them, control them, emit them, attract them, to build the urban markets of capitalism. The city thus aims to be a continuous, intense and massive flow of goods, people, capital, goods services and screen-images. These tangible and intangible flows are hardly compatible with the fragile anchors of public sociability, the symbolic sedimentation of urban cultures and the strolling slowness of the inhabitants in the commons of the city. Either the flows or the commons: the city cannot belong to both at the same time.

In addition to sprawl and metropolization, social and ethnic segregation greatly contribute to breaking up the city. Paradoxically, the ultra-mobile city implies social and ethnic borders that form a barrier between the classes and the sociocultural groups living in the city. Hyper-mobility of the few, constrained sedentary lifestyle of many: the residential segregation of the inhabitants is prolonged in their mobility within the city.5 The latter, therefore, refers less and less to common and shared experiences of its inhabitants and depends increasingly, and by now overwhelmingly, in many metropolises on whether one is rich or poor, immigrant or not, young or old, man or woman, etc.

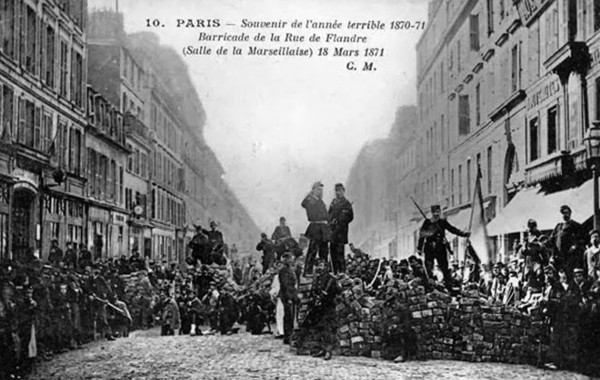

Finally, a fourth process breaks symbolically the city-commons: the questioning of urban monumentality. While the equestrian statues of the monarchs, the imperial triumphal arches and the war memorials symbolically reflected the feeling of common belonging in the cities, it is clear today that cities face great difficulty to “reinvent tradition” in their monuments. Instead of such a reinvention, we are most often witnessing a process whereby patrimony and tourism defines historic centers. The kitsch, standardized and disposable folklore of the tourism industry, seeks to attract tourist flows to the ancient centers, thus smoothing the cultural singularities of the heritage of cities in many “products” that are more or less homogeneous. The urban world, therefore, seems to be orphaned today by a symbolic and emotional commons, as if it no longer manages to display a horizon of expectations shared by its inhabitants.

The only monumentality produced by these dispossessed cities has a postmodern character: it is by definition ephemeral, itself a commodity and a brand at the same time, like the great American malls and other shopping centers, the IKEA stores or the skyscrapers of central business districts. These commodity-monuments present themselves to the eyes of the inhabitants with no past and no future: they do not convey any “field of experience” and do not project any “horizon of expectations” according to Reinhart Koselleck’s categories. Imprisoned in contemporary “presentism” (François Hartog), they, in turn, trap the gaze of the inhabitants. The merchant present is represented as a duration without origin and without end, putting an end to the different articulations of time past / present / future of modernities. The glass and steel skyscrapers thus present a transparency that seems to refer as much to the extreme plasticity of capitalism as to the collective symbolic and ideological emptiness. Dreamless cities, cities without shared horizons, fragmented and commodified cities. The conditions of possibility of “classic” or modern urban monumentality thus seem to have disappeared.

The oft-announced death of urban commons cannot, however, be written in advance. There is nothing inevitable about it. If the city-commons has been bequeathed to us as a historical construction prior to capitalism, its capture and destruction by the latter in no way prevents its post-capitalist reinvention today on new bases. The city-commons, therefore, shares the fate of other commons and, in the same manner, depends on the outcome of the ongoing struggles to rescue them.

Field of Possibilities

The breaches opened by the planetary event of the pandemic that we are experiencing today are, in this sense, breaches in the field of possibilities. “History is nothing but the succession of the separate generations,” explains the young Marx in The German Ideology (1845-1846): an open process in which politics takes precedence over history, the present over the past. Henri Lefebvre’s “right to the city” and its variations remains an actual radical political program (as with David Harvey’s call), and as activist groups against the gentrification of the world’s major cities have shown.

To defend the city-commons that is threatened today, it might be useful to draw inspiration from the defense of other commons in the world. French anthropologist Philippe Descola suggests in this sense for the commons of the Earth, such as rivers or forests, to reverse the process and to start not from the right of their inhabitants to the free use of these commons, but rather, from themselves in order to make them living environments protected by law.

“Against the idea that humans have for vocation the appropriation of the world, rights conferred on living environments – and not on nature which is a dangerous abstraction, or on predatory humans – are rights on which the humans who occupy these environments depend, and it is no longer these humans who are the source of these rights. It is a game-changer, it is humans who are appropriated by the living environment, not the other way around. It seems fundamental to me if we want to go against the centuries-old movement of devastation of the planet.”6

In this context, insisting on an urban commons becomes something of a revolutionary banner and a call to battle. •

This article is a translation of an original version that was published in French, “La ville privée des communs” in Entre-Temps, online history journal, May 4th.

Endnotes

- “The interpretation developed in this article is inspired by the architect Jean Harari, «Le capitalisme contre la ville,» Contretemps. Revue de critique communiste, no. 44, janvier 2020, pp. 8-17. He himself situates his analyses of the city today in the wake of the work of Henri Lefebvre, David Harvey and Mike Davis.

- In this way, it is possible even to view “the metropolis as a factory for the production of the common.” The human qualities of the city emerge from our practices in its diverse spaces, even as those spaces are subject to enclosure both by private and public state ownership, as well as by social control, appropriation, and countermoves to assert what Henri Lefebvre called “the right to the city” on the part of the inhabitants. Through their daily activities and struggles, individuals and social groups create the social world of the city and, in doing so, create something common as a framework within which we all can dwell. While this culturally creative common cannot be destroyed through use, it can be degraded and banalized through excessive abuse.” David Harvey, “The Future of the Commons,” Radical History Review, no. 109, winter 2011, pp. 103-04.

- Michael Hardt and Toni Negri, Empire, Paris: Exils/10-18, 2000.

- Empire, p. 465.

- John Urry, «Les systèmes de la mobilité», Cahiers internationaux de sociologie, no. 118, 2005/1, pp. 23-35.

- «L’Amazonie et les «zones à défendre». Entretien avec Philippe Descola», Contretemps. Revue de critique communiste, no. 42, juillet 2019, p. 142.