Make UK Public Transport Free

In mid-August, to uproar from the right-wing press, teen activist Greta Thunberg set sail in a zero-emissions yacht on a two-week trip across the Atlantic to reach the UN climate talks in New York. Taking her role as figurehead of the global school strikes for climate movement seriously, Greta shuns air travel for its high levels of emissions production, recently completing a tour around Europe entirely by train.

The problem Greta identifies is a real one. Flying is responsible for about 3.5 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions, and is often the cheapest and easiest option for domestic travel or short-haul to western Europe. But emissions aren’t limited to air travel. From planes to cars – which still dominate UK travel both locally and nationally – our most popular transport systems are largely carbon intensive, with one-third of the UK’s CO2 emissions coming from transport.

The problem Greta identifies is a real one. Flying is responsible for about 3.5 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions, and is often the cheapest and easiest option for domestic travel or short-haul to western Europe. But emissions aren’t limited to air travel. From planes to cars – which still dominate UK travel both locally and nationally – our most popular transport systems are largely carbon intensive, with one-third of the UK’s CO2 emissions coming from transport.

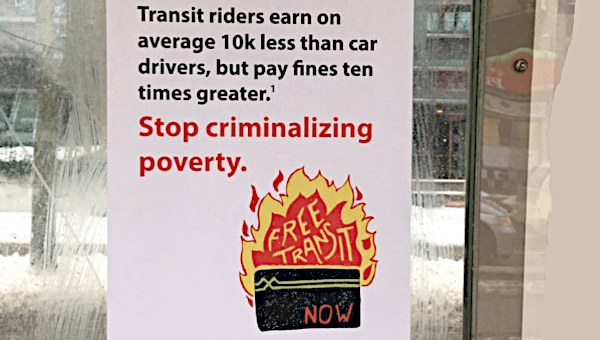

And it’s no wonder we choose these forms of transport compared to the alternatives. Public transport in the UK is expensive and inadequate. Rail fares will be hiked again in January, imposing a 2.8 per cent increase on consumers and adding over £100 to many already extortionate annual season tickets. Despite paying five times as much of our salary in the UK on rail travel compared to our European neighbors, delays and overcrowding are common. In rural areas and even cities, limited bus routes cut in half by Tories since 2010 mean irregular services and many areas not connected at all. The crisis of rural public transport has left communities cut off from the rest of society, unable to access work and vital services.

Radical Structural Alternatives

But while Greta’s journey reminds us why we can’t revolutionize our transport systems quickly enough, we can’t all simply replicate her actions. Environmentalism of personal virtue, impressive though it may be, has proven unable to deliver the change we need. For decades we’ve been trying to reduce our individual carbon footprints by flying less and cycling more – and yet we’ve only shrunk our carbon emissions by 3 per cent since 1990.

Instead, we should be building radical structural alternatives to flying and private car ownership. High-quality, zero-carbon transport should be as effortless and enjoyable a choice as possible – not one denied to all but a privileged few.

One framework for revolutionizing public transport to work for people and planet is the Green New Deal – a government-led program of investment and regulation to decarbonize society and transform the economy, popularized by US congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in the United States. Under a Green New Deal, the burden of responsibility for transport emissions reduction would fall on society as a whole, and not on individual commuters.

Campaigns in the UK such as our own Labour for a Green New Deal have called for universal basic services to help deliver this transformation. Free public transport for all, covering local, national, and international travel, should be central to what these services aim to provide.

Locally, this would mean government investment in expanding the provision of bus services across every village, town, and city. Democratic municipal planning could give residents power to ensure buses are electrified, routes and timetables meet local needs, and services are free at the point of use.

At a regional level, a Green New Deal could see investment in our railways shared equitably across regions, bringing the infrastructure of the North and Wales to parity with London and the Southeast. As well as guaranteeing free travel between towns and cities across the country, we should strive for the highest standards: the shortest possible journey times, guaranteed charging ports, free Wi-Fi, and a seat.

This comprehensive provision of free public transport lays the foundations for a necessary shift across society away from private car ownership. Cars sit unused 95 per cent of the time, and yet they dominate our society. For cases where cars are still necessary for people with disabilities or workers in certain industries, our starting point could be collectively owned fleets of electric vehicles for shared use, as well as worker-owned Uber alternatives.

With UK car manufacturers increasingly under threat, a Green New Deal could ensure electric cars for these fleets are made democratically by those already skilled workers. While electric cars are no silver bullet when it comes to the climate crisis due to their demands on energy, natural resources, and space, if commonly owned, they could nonetheless become a zero-carbon transport alternative.

The level of investment in transport infrastructure required is undoubtedly a huge undertaking and will command serious financial and human resources. This challenge provides us with the opportunity to kickstart the Green New Deal’s program of providing well-paid, unionized, green jobs while accelerating investment in the green technologies needed to transform the entire economy.

Like the Green New Deal as a whole, investment in public transport infrastructure should not be limited to national borders. It offers an opportunity to move beyond them. Beginning by expanding existing rail links across Europe, reducing journey times and slashing prices would create the conditions to fully transition out of domestic and short-haul aviation within five years. Paired with the greater leisure time of a shorter working week, a global living wage and a workers’ sabbatical, a global Green New Deal could allow anybody in the world to travel to anywhere else by public transport.

Not Just Decarbonization

Ambitions for investment in upgrading infrastructure on a global scale underlines that the Green New Deal cannot have a myopic focus on decarbonization alone. Asad Rehman writes that simply switching from fossil fuels to zero-carbon technologies does not end the unsustainable and colonial extraction of rare earth metals such as cobalt needed for electric batteries.

Our response should not be to abandon a vision of climate justice based on abundance and prosperity for the many, but to embrace what George Monbiot has termed “private sufficiency and public luxury.” The demand for free public transport for all exemplifies this. In migrating en masse to free public transport, we do forfeit some of the autonomy afforded by personal car ownership or the convenience of flying short distances very quickly. This, however, is offset by the shared social and environmental benefits of public ownership, democratic planning, and communal travel.

The plan to decarbonize, democratize, and decommodify public transport should become a flagship pillar of the Green New Deal’s early stages. Through public luxury, it will begin to reduce aggregate demand for energy and resources while eliminating emissions in the transport sector. The social and financial benefits will be enjoyed by the whole of society while we lock the economy into zero-carbon infrastructure. The Green New Deal must include free public transport for all.

This article first published on the Tribune website.