A World Transformed 2025: Britain’s Left-Wing and Experiments in Democracy

The biggest left-wing event in Great Britain – The World Transformed – was held regularly under the patronage of the Labour Party from 2016 onward. Since the party under the leadership of Keir Starmer adopted far-right rhetoric, the festival organisers have distanced themselves from Labour and this year organised the event in Manchester independently, in collaboration with several independent organisations. What does the festival reveal about the future of the British and, ultimately, the global left?

In front of the Niamos cultural centre, an old theatre that transformed in the 1980s into a centre for the Black community, where Fela Kuti1 and Nina Simone once played, stands a long queue of people. I arrive at the event half-an-hour early, but even so I’ve underestimated it. The end of the queue is nowhere in sight. I walk along the patiently standing crowd, pass the entire street, turn the corner, and at the end of the alley the queue continues around another corner, and this repeats several more times. One might think that the endless crowd is waiting for some rockstar or Hollywood star. In the Niamos, however, there will only be a discussion with a group of left-wing politicians: Peter Mertens from the Workers’ Party of Belgium,2 Janis Ehling from the German Die Linke,3 Nathalie Oziol from La France Insoumise.4

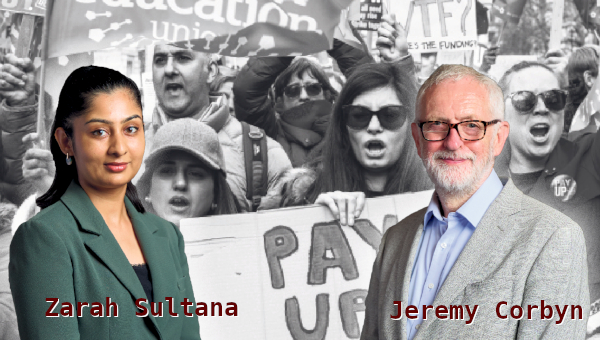

But especially: Jeremy Corbyn and Zarah Sultana from the just-emerging Your Party. It’s because of them that people are standing outside even in the damp autumnal English weather. After half an hour the queue moves, and I’m the last one they let inside. Outside remain hundreds of people who no longer fit into the theatre. Welcome to The World Transformed.

In the Sign of Gaza

Two years ago, the festival was held in Liverpool and began on 7 October, on the day of the Hamas attack on Israel. This year’s event kicked off on 9 October, on the day when a ceasefire was agreed to between Israel and Hamas (and mediated by US, Egypt, Qatar, and Turkiye), which for two years had been committing genocide in Gaza.5 The fact that the festival is framed by these two events is, whilst coincidental, very symbolic. I repeatedly hear, from festival attendees and performers, that the genocide in Palestine has fundamentally changed the British left. Words like ‘revitalised’, ‘energised’, and ‘awakened’ are used. Therefore, it’s no surprise that the festival begins with a large pro-Palestinian protest march from All Saints Park to the Hulme neighbourhood, where most of the programme takes place.

Palestine is everywhere you look. Several independent discussion panels are dedicated to it; Palestinian guests debate in many others as well. It’s almost impossible to hear a speech from any activist or politician in which support for Palestine doesn’t resound. In the stalls with left-wing literature are dozens of books about Palestine. T-shirts, badges, scarves, flags, bracelets, and bookmarks. For young English leftists, the liberation of Palestine is clearly a fundamental issue.

“Sadly, it was this terrible genocide that revitalised and awakened not only the British left but also wider British society. We witnessed a great mobilisation. In my opinion, however, a major problem for the British left and progressive forces generally is that they are very good at mobilisation – Great Britain has proven this repeatedly, whether in 2003 during the Iraq War or now, when millions of people took to the streets in support of Palestine. The problem, however, is that it can’t transform this into more lasting organisation,” Kurdish activist Elif Sarican told me. She moderated a panel at the festival on the possibilities of women’s movements in the fight against rising fascism. Sarican means organisation at the political level, but the organisation of this festival itself is already very impressive.

During three days, 120 discussions, lectures and panels took place – meaning that every hour several events were happening simultaneously. Enthusiasm for the rich programme could thus mix with an anxious feeling of FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) about what was being missed. Just for illustration: at the same time a panel on trade union organising in culture, a discussion on striking, a debate on the EU and NATO, a panel on gentrification, a discussion on socialist climate strategies, a meeting with representatives of the Palestinian diaspora, and a guided walk through Hulme were taking place. Take your pick.

The Ethos of Protest

Whatever you chose, all events enjoyed high attendance, whether they took place in the large modernist Ascension church, the Niamos theatre, or in the smaller Windrush community centre. And often you couldn’t even get into the chosen programme. The interest of (mostly) young people in left-wing and political topics was enormous, the positive energy with which they approached discussions infectious. I envied them a bit that they lack our Eastern European cynicism and skepticism.

The hopeful atmosphere was enhanced by the fact that the event took place precisely in Manchester. If you want to understand where the ethos of protest that resonated throughout the festival came from, I recommend visiting the Manchester People’s History Museum. On three floors, it presents the entire history of English protest movements – from the Chartists6 through the first trade unions, strikes, feminism, and socialism to struggles for the rights of trans people. The museum is, moreover, conceived so that it entertains children and doesn’t bore adults. So it can happen that whilst reading materials about the socialist cycling club Clarion,7 a group of small girls runs past you with period suffragette banners, shouting: “We want the vote!”

Manchester was also, in 1945, witness to the Fifth Pan-African Congress,8 which was attended by, for example, the famous American sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois and Kwame Nkrumah, later the first president of independent Ghana. At the festival, this event was commemorated with several panels and discussions, and these were among the best I saw.

The tradition of protest and civic activism is also strongly associated with the Hulme neighbourhood, where from the 1950s many battles were fought for workers’ rights, migrants’ rights, and affordable housing. And you can feel it at every turn. One of the community centres where the festival programme took place, the Kath Locke Center, is named after a prominent Black activist from this locality.9 And there are several similar centres in the neighbourhood. The large garden centre in front of the Niamos theatre, where festival attendees gathered most of the time, was until recently a car park, but residents secured its transformation into a living green community space.

A lesson for an Eastern European: civic activism isn’t born overnight, it accumulates over entire generations, it becomes an organic part of the community’s thinking and living. In Manchester, there is clearly something to build on – the foundations are there. The question of the festival, sometimes unspoken but often explicit, was how and what to build on those foundations now.

Our Party

Let’s return, however, to the packed-to-bursting Niamos theatre, where Jeremy Corbyn and Zarah Sultana appeared. When, in July, Sultana announced that she was leaving Labour and founding a new socialist party with Corbyn, left-wing circles almost immediately began placing great hopes in the party. These, however, faded just as quickly when internal party conflicts came to the surface, visible already in disagreements concerning the registration of new members. Although the party later tried to present this as merely an administrative error, it was clear that it was a deeper, ideological internal dispute. That’s also why so many people came to the Niamos theatre: they were curious how the two leaders, who until then had been sending each other messages mainly through social media, would address the resolution of disputes. And honestly, I was curious about this too.

In this respect, however, we remained disappointed. Although Corbyn and Sultana received a warm welcome and at times thunderous applause, the speeches themselves didn’t bring so much joyful response. Both emphasised that today the most important thing is to prevent an electoral victory by the far-right Reform UK.10 “We must defeat the fascists in the polling stations, but, when necessary, we must also fight them in the streets,” Sultana declared at the outset. She then mentioned several points of her agenda, among other things the struggle for trans people’s rights and the intention to sever all diplomatic ties with Israel. Her vocabulary and presentation were more radical than Corbyn’s, and it seemed that she had greater support among younger people. She speaks their language, knows how to work with an audience.

In the end, however, both remained only with more-or-less rehearsed political phrases. I had the feeling as if I were at a pre-election rally where potential new voters need to be persuaded, which certainly didn’t apply in this case. In the Niamos theatre, they were at home; everyone there was favourably disposed toward them. It seems to me that people came here for a nutritious lunch and got only a decent breakfast. After the discussion, I spoke with several participants, and a perplexed impression prevailed. “Deep disputes persist in the party, which they haven’t succeeded in resolving for a long time,” noted one party member who didn’t wish to be named. “What came to the surface is only an expression of these disagreements. And unless they resolve them, it will repeat itself, and probably it will be much worse,” he concluded.

After several days in Manchester, I had the feeling that the victor of these internal battles is Zack Polanski, the new leader of The Greens.11 He participated in several panels, is very relaxed, entertaining, self-confident. One evening he even hosted the large festival pub quiz. His party is growing in the polls. In the most recent one, it overtook Labour for the first time. It’s obvious that he has momentum, and he’s aware of it. Several people confirmed to me that after the initial fiasco of Your Party they’re considering voting Green. There’s still a long way to the elections, but it’s already clear today that one of the alternatives for left-wing voters could be some form of so-called red-green cooperation.

Experiment in Democracy

Bitterness about the manner of leading the new party is palpable even during the so-called General Assemblies. They take place every day in Ascension church, last several hours, and the interest in them is enormous. In the hall sit hundreds of people, others press against the wall or sit on the floor. Under the direction of the well-known British journalist Ash Sarkar,12 a large plenary meeting takes place, where everyone has the opportunity to speak – not only about the functioning of Your Party, but also about general questions, the future of the British left, and building a wider social movement. Many contributions are heard: some prepared, others improvised. Anyone can respond; people patiently raise their hands and wait for their turn. The organisational team records everything and always the next day publishes a bulletin summarising the main points of the assembly.

Different speeches get space: from radical to moderate, from idealistic to pragmatic. Many of them concern the leadership of Your Party – several people are dissatisfied, calling for a wider movement that wouldn’t rely only on a few elected representatives. The problem of representation is also often addressed. “What significance do the conclusions from this meeting have, which impressively fills a large hall, but is still only a few hundred people? What about people with disadvantages who couldn’t come?” one participant asks. “And are there enough trans people represented here?” another asks.

At one point, a man speaks up who introduces himself as a refugee from Syria. “There’s much talk here about the rights of migrants, refugees, or people waiting for asylum. However, it’s necessary to hear our real voice. But how many of us are at this assembly today?” From the hundreds of people, one shy hand is raised. I have a hunch that if someone asked about the representation of working-class people, the answer would be similar.

Despite these shortcomings, which probably no large assembly can avoid, it’s fascinating to watch the entire process. Communication takes place very politely, mostly also constructively. And above all you can see that people are genuinely interested in this social dialogue. They listen attentively. They learn to formulate their thoughts and receive feedback. I try to imagine something similar, on this scale, in Slovakia, but I don’t succeed very well.

Calm on the Eastern Front?

Discussions follow one another, many topics are opened, support for Palestine is constantly accentuated. One topic, however, is completely absent: the war in Ukraine. Together with my Eastern European journalist colleagues, I’m at first uncertain, later annoyed and disappointed. At no event, however large, is it, of course, possible to discuss all topics. The war in Ukraine, however, is still such a fundamental conflict with its global implications that its absence is striking. And reveals much. No Ukrainian guests, no panels, zero support.

It’s as if Ukraine in the environment of the British left simply doesn’t exist. What is heard often, however, is withdrawal from NATO. Magdalena Dušková from Alarm (a Czech left-wing magazine) told me about her experience. “The entire event spoke a lot about imperialism and the fight against fascism. In this context, however, nowhere was it mentioned that besides Western imperialism there exists Eastern imperialism and fascism. The kind that attacked Ukraine and against which it’s necessary to defend. In discussions about demilitarisation there wasn’t a single person who knew the context of Eastern Europe. Everyone spoke about how important it is to demilitarise. However, no one thought to talk about what this means for our friends in Ukraine. A guest at one panel even implied that Ukraine is to blame for being attacked because it was arming itself, which was the moment when I left the hall.”

The World Transformed is a good litmus test of the contemporary Western left, for good and ill. It shows its hopes, disappointments, small victories, and failures. From the perspective of an Eastern European, it’s a strangely bittersweet experience: in many ways inspiring but often pointing to the limits of international solidarity. “A new world is not only possible, it’s already coming. Perhaps many of us won’t greet it, but on a quiet day, when I try very hard, I can hear its breath,” writes Arundhati Roy13 in the essay Capitalism: A Ghost Story. The tremors of this new world could be heard in October this year in Manchester as well. And although I didn’t agree with everything I heard, it’s always better than deafening silence. •

This article first published in Slovak on the Kapital website, and English on the Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières website.

Endnotes

- Nigerian musician, political activist and Afrobeat pioneer (1938-1997).

- The Workers’ Party of Belgium (Partij van de Arbeid van België/Parti du Travail de Belgique) is a Marxist political party founded in 1979.

- Linke (The Left) is a democratic socialist political party in Germany formed in 2007.

- France Insoumise (France Unbowed) is a left-wing political party in France founded in 2016 by Jean-Luc Mélenchon.

- A ceasefire agreement between Israel and Hamas was announced on 8-9 October 2025, brokered by the United States with mediation from Egypt, Qatar, and Turkiye. The deal included the release of all remaining Israeli hostages in exchange for Palestinian prisoners.

- The Chartists were a working-class movement for political reform in Britain between 1838 and 1857 that sought universal male suffrage and other democratic reforms.

- The Clarion Cycling Club was founded in 1894 as part of the socialist Clarion movement, combining recreational cycling with political activism.

- The 1945 Pan-African Congress in Manchester brought together anti-colonial activists including Kwame Nkrumah and W.E.B. Du Bois to demand African independence.

- Kath Locke was a Black community activist and youth worker in Manchester who fought for racial equality and community development.

- Reform UK is a right-wing populist political party led by Nigel Farage.

- The Green Party of England and Wales is a left-leaning political party focused on environmentalism and social justice.

- Ash Sarkar is a British journalist, political commentator and contributing editor at Novara Media.

- Arundhati Roy is an Indian novelist, essayist and political activist, author of The God of Small Things.