The Crisis of the Care Economy in Africa

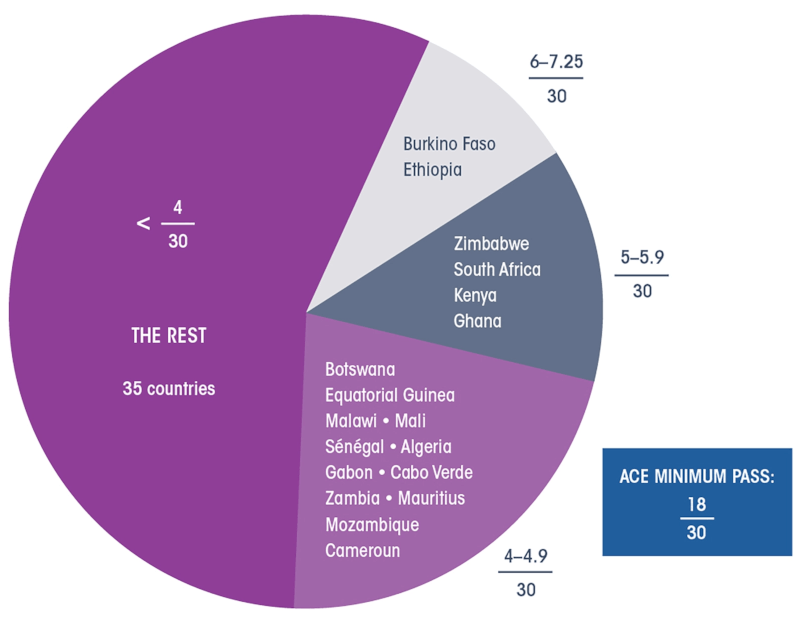

A country that attains the passing grade on the UNDP’s Africa Care Economy Index is one that has basic minimum legislation and public spend in place to ensure a population that is able to take on the challenges of development as well as manage future pandemics. But not one African country scores more than half of the passing grade.

With the rise of illness and death during the global COVID-19 pandemic, discussion about the work of caring has returned to public policy discourse around the world – but not so much in Africa. This is despite other epidemics that have hit the continent in recent decades, including Ebola and HIV/Aids.

An October 2022 post by United Africa, a Facebook group with 74,000 followers, illustrates the underrecognition of care on the continent. It features an 1899 photo of Mohamed carrying Samir on his back. Mohamed is blind and Samir is labelled “a dwarf.” The two are described as orphans who relied on each other: on the streets, Samir would give directions while Mohamed did the walking. Samir would tell stories for pennies outside a cafe, and Mohamed would listen while selling wares. Together they survived into adulthood.

What is emphasised in the United Africa post is that Mohamed and Samir coexisted even though one was Muslim and the other Christian. Nothing is said of the interdependence and care of two individuals living with what are now known as disabilities – estimated to affect up to 40% of Africa’s population. Care is both assumed and ignored.

Demand for Care

Despite the immense need for care in Africa today, little is done by states or by society at large to recognise, support and respect care. The demand for care in Africa arises from the following realities:

- The continent boasts the world’s highest birth rate, at four live births per woman;

- The bulk of food consumed is produced through subsistence farming; and

- The ill and elderly are cared for at home and in communities in contexts of war, violence and longstanding impoverishment.

Africa has been noted as the region with the “most unshared system of care,” where more than 70% of care is provided by unpaid, individual caregivers in homes and communities.

This compares with the “shared system of care” in Europe, North America, Australia and Japan, and the “semi-shared system of care” in Latin America and Asia, where the work of caring is shared collectively through public, private and community-run programmes and institutions.

In Africa, the vast majority of caring work is done by women and girls. The health of women in Africa is particularly poor. About 30% of women around the world are anaemic, for instance, and more than half of these women are in Africa.

Women and girls are “time poor” – the time they spend on housework and other caring is far greater than time spent on these tasks by boys and men. This takes away the possibility for girls and women to benefit from education and paid work.

The gap in caring work done by women and girls versus men and boys in Africa ranges from over 16 times more by women and girls in Egypt, five times more in Senegal and two times more in South Africa.

The United Nations Development Programme’s (UNDP’s) Africa Care Economy Index attempts to draw attention to this dire reality. Change is crucial to improve the wellbeing of women and girls, as per the 2007 African Feminist Charter, but also to materialise Africa’s demographic dividend into greater collective wealth.

Demographic Dividend

The demographic dividend is based on the estimate that Africa will have a larger working-age population by 2100 than all other continents combined. The numbers look something like this: Africa will have 2.1 billion people aged 15 to 64, whereas the rest of the world will only have about 2 billion people of working age.

Economists assume this will translate to massive future economic growth in Africa. They prescribe investment in healthcare and education to strengthen the capabilities of this large potential working population. Nothing is said about the caring work that underpins the effectiveness of healthcare and education to turn young people into productive workers.

Without making the political choice to recognise, respect and support care on the continent, African countries will continue to falter, regardless of the potential of a growing workforce.

The account featured at the beginning of the Africa Care Economy Index paints a vivid picture of the consequences of this.

Though exceptional in some respects, the account rings true of realities throughout the continent and demonstrates that Africa’s socioeconomic underperformance will continue if the neglect of care and caregivers is not reversed. (Names and markers have been removed to protect anonymity.)

“Jane, a licensed massage therapist in Africa, travelled overseas to support her country’s team in a world competition of mobility-impaired sports. On arrival, Jane was given the responsibility of providing medical care – something she was not trained for nor told about in advance. One player, Sylvia, suffered from recurring wounds that needed regular dressing.

“Taught from a young age to dress her own wounds by nurses over the years, Sylvia gave tips to Jane on what to do. Attempting to learn fast on the job and under pressure to assist several players, Jane supplemented Sylvia’s tips by watching YouTube videos.

“Sylvia lost a limb after enduring a burn by boiling water as an infant. Daughter of a single working mother who lacked funds for a childminder, Sylvia was in the care of two other children when the accident happened. The details of how the burn occurred were never known.

“On returning from the competition, overwhelmed by the trying experience, Jane cried for two days. Sylvia’s remaining limb was amputated as it came to be understood that the recurring infections were due to tissue that had never healed after the burn. After the amputation, Sylvia felt liberated, though she never played for the national team again.”

How the Africa Care Economy Index works

The Africa Care Economy Index (ACE) evaluates each of the continent’s 54 states in terms of how well they recognise and support caring work through legislation, policy and public spending.

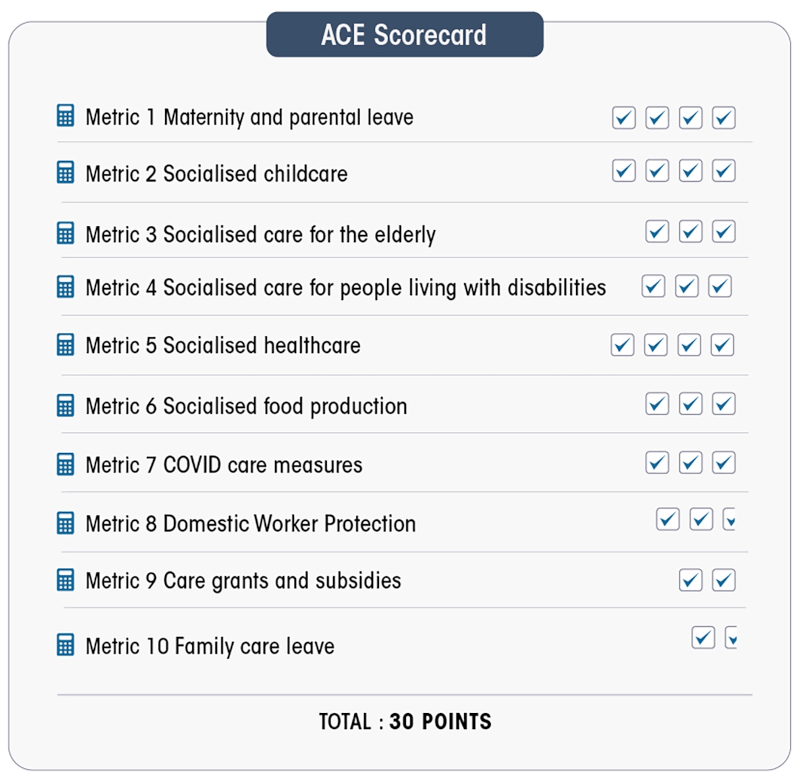

Ten categories or metrics are used. Each metric represents a different aspect of the care economy. Legislation, policy, or/and public spending related to each metric are analysed to determine how well – or how poorly – African states recognise and support care.

Each metric is worth between 1.5 and four points (see the check marks in the figure), depending on its significance and importance in the African context. Countries are graded on a total of 30 points. Full points in a metric mean that for that category of care, a country has comprehensive and inclusive legislation or acceptable public spending.

The passing grade in the ACE Index is 18/30, or full points in the following six metrics:

- Maternity/parental leave;

- Socialised childcare;

- Socialised care for the elderly;

- Socialised care for people with disabilities;

- Socialised healthcare; and

- Socialised food production.

Socialised care is care that is publicly financed and provided, in non-profit models, to all who need care, regardless of income level. Using examples from around the world, the index shows how socialised care outdoes private, paid care in terms of quality, as well as training and respect for caregivers.

A country that attains the passing grade of 18/30 is one that has the basic minimum legislation and public spending in place to ensure a healthy population that is ready and able to take on the numerous, historical challenges of development in Africa.

Full points in the first six metrics (18/30) also mean that a country is ready to face future pandemics that are predicted for Africa and the world because of the ecological destruction that has intensified over the past 70 years.

All African countries feature extremely low, scoring less than half of the passing grade. Only six countries score a total of more than five points out of 30. The rest, or 46 countries for which there is sufficient data, score 4.9 or less out of 30.

What Is To Be Done?

The ACE Index results may not be altogether surprising, but they are shocking all the same. Given the breadth of Africa and its multiplicity of political, geographic and social characteristics, in-depth, country-specific research is needed to begin undoing the neglect of care and caregivers on the continent.

For each metric, the index identifies key questions for policy research, organising and change, underlining that the forms of socialised care in African countries must be discussed and debated among each country’s multiplicity of peoples.

Rather than a top-down process geared toward emulating models of care in rich countries, socialised care in Africa must be defined at the grassroot level, as part of a larger process of democratising and decolonising economies.

Socialised elder care in African countries, for example, will surely look different than the institutionalised care typical in Europe and North America – a form of care which COVID-19 has exposed as questionable even for Europe and North America.

The culturally and socially appropriate forms of socialised elder care, childcare and other care in Africa are for each African society to define, with the goal of alleviating the weight of caring work from the shoulders of unpaid, unrecognised and predominantly female caregivers.

Far from a concern of women alone, this is a collective concern around which Africa, and beyond, must engage. A first step is to read the Africa Care Economy Index, and spread its word. •

This article first published on the Daily Maverick website.