‘The Canary in the Coal Mine’: Sri Lanka’s Crisis is a Chronicle Foretold

Sri Lanka’s acute economic crisis and sovereign debt default, along with its people’s uprising in 2022, has drawn attention across the world. It is described as the ‘canary in the coal mine’, that is, a harbinger of the likely future for other global south countries. Eric Toussaint, spokesperson for the Committee for the Abolition of Illegitimate Debt (CADTM) interviewed via email Colombo-based Balasingham Skanthakumar of the Social Scientists’ Association of Sri Lanka and the CADTM’s South Asia network. The responses in draft were improved by Amali Wedagedera’s review and finalized on 5th August.

Eric Toussaint (ET): What was the cause in Sri Lanka for the people’s uprising in 2022?

Balasingham Skanthakumar (BS): Sri Lanka ran out of foreign exchange in the first quarter of 2022. It exhausted its reserves, already depleted from defending the value of the Lankan Rupee (LKR), having serviced a $500-million (US) International Sovereign Bond that matured in January. New inflows to renew reserves, confidently assured by the Central Bank Governor on behalf of the Gotabaya Rajapaksa administration, did not materialize.

For decades, there has been a chronic balance of payments shortfall, such that import expenditure raced ahead of export revenue, two-to-one. This deficit has been financed by foreign borrowings (initially bilateral and multilateral loans, but increasingly the international money market from 2007 during the Mahinda Rajapaksa presidency). In fact, the so-called foreign reserves were almost entirely foreign loans and not national income. To maintain the LKR at an artificially high value for almost a year, the Central Bank drew down on its dollar holdings. Once the reserves were exhausted, the rupee went into freefall in March 2022. It lost 44% of its value against the US dollar, and around 40% against other convertible currencies between January and May 2022 alone. Presently the US dollar trades at LKR361, whereas in June 2021 it was LKR200.

Without foreign exchange, highly import-dependent Sri Lanka could not afford to purchase fuel (petrol, diesel, coal, kerosene, LP gas), food, and medicines. The shortages of fuel affected not only transport but also the generation of electricity, making previously rare power cuts a daily and prolonged occurrence from February up to the present. With shortages of food and other essentials in the market, queues of people formed everywhere. The price of everything rose sharply. By July, headline inflation surged over 60% – food having skyrocketed by 90% and non-food items by 46%. One in three persons is food-insecure: without adequate access to food or reducing the number of meals, the portion sizes, quality, and variety. Community kitchens have begun in Colombo with crowd-sourced funding to provide at least one meal a day in low-income areas, along with ad-hoc distribution of cooked food parcels.

Fuel shortages and power cuts also debilitate the productive sectors of the economy spanning farming, fishing, and factories. The livelihoods of daily-wage earners and urban poor households are devastated. The crisis has decimated the incomes of low-paid gig workers who run taxis and deliver food. The savings and retirement benefits of the middle and working classes have more than halved following devaluation of the rupee. Those on fixed incomes are losing ground to inflationary price hikes propelled by profiteering, without compensatory wage increase. Tens of thousands of mainly young people throng the passport office, their first step to find jobs abroad. Several hundreds have been intercepted at sea, trying to escape in unsafe and overcrowded fishing boats to India or Australia.

Public discontent over the brewing crisis was evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, with farmers, schoolteachers, garment, and plantation workers’ protesting in 2021, as did women victims of microfinance loans in 2020. There were set-piece anti-government demonstrations and rallies by opposition political parties but only mobilising the faithful. Meanwhile the government kept downplaying the seriousness of the economic problems. People across classes were disenchanted by a government that was indifferent to their pain and inactive even as they suffered.1

The Rajapaksa family that has dominated Sri Lankan politics since 2005 has been the object of both adoration and fear within society, depending on one’s ethnicity and political views. For the first time in a generalized way, stories of their abuse of power, attachment to astrologers, and unexplained wealth, became openly ridiculed. The demand for President Gotabaya Rajapaksa to “Go Home!” included the rest of his family too. This slogan was joined by another, “Give us our stolen money back!” Even though cross-class grievances indicate a systemic crisis, the citizens’ movement that emerged in 2022 was largely framed by the middle-class belief that the mismanagement of the economy derives from grand corruption among politicians and bureaucrats.

This people’s uprising is heterogeneous, without structure or leaders. It defies neat class labels. Its origin from within that inexact category of the “middle class” has shaped its character and consciousness. However, along the way it has become more diverse, receiving support from university students, daily waged workers, the urban poor, pensioners, people with disabilities, trade unionists, the clergy, and the LGBTQI community. Still, the active participation of the working class, farmers’, fishers’, and plantation workers, is minimal. Even the left-wing representatives of dominated classes who participate in it, have not been able to transcend the general demand within the citizens’ movement for short-term economic relief; nor advance an agenda beyond regime-change and liberal democratic and constitutional reform.2 The left has neither programme nor strategy for the socio-economic transformation of society and working peoples’ power.

ET: What were the stages of the mobilizations of the last months?

BS: In an organic way, handfuls of middle-class citizens began organizing neighbourhood protests in the largest city Colombo and its suburbs.3 As the crisis gathered pace, so did the numbers and the spread of the movement. There was a qualitative turn on 31 March when youth were violently attacked during a confrontation with security forces guarding Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s private residence. Thereafter the protests, including outside of Colombo, grew in leaps and bounds. Some organizers, unconnected to political parties and new to activism, proposed a convergence of the protests on a symbol of presidential power, his office by Galle Face Green, Colombo’s seaside park.

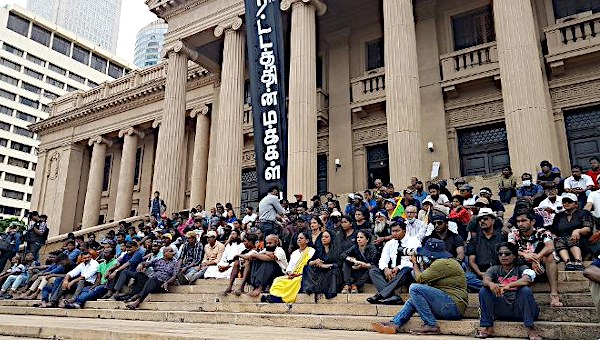

This massive demonstration of tens of thousands from across the island that began on 9 April turned into a continuous occupation (#OccupyGalleFace), denying Gotabaya Rajapaksa access to the Presidential Secretariat right up to his resignation in July. Elsewhere across Sri Lanka, people became inspired to occupy other public spaces demanding the resignation of the president, his family members, and the government.

However, the largest and most iconic occupation was in Colombo, dubbed by its residents as ‘GotaGoGama’.4 In the Sinhala language, ‘Gama’ means village. What began as a couple of tents to provide shelter for those who stayed on, organically grew into a commune with a kitchen, library, dance and drama performance spaces, a film hall, vegetable garden, western and ayurvedic medical care, solar-powered energy for mobile telephone charging, along with encampments of the deaf community, Catholics seeking justice for the 2019 Easter Sunday terrorist bombings, campaigners against enforced disappearances and for human rights, and numerous youth organizations including of the leftist Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (Peoples Liberation Front) and Frontline Socialist Party.

Another significant stage in the citizens’ movement began on 9 May, when supporters of then Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa attacked the protest sites (#GotaGoGamas) in Colombo and Kandy. There was instant solidarity from the public. The political violence provoked counterattacks by enraged people previously inactive in the protests but in passive agreement with it, directed at government politicians and their properties. This forced Mahinda Rajapaksa’s resignation.

Gotabaya Rajapaksa soon appointed former political rival Ranil Wickremesinghe as prime minister. Wickremesinghe, along with his United National Party (UNP) that was in government between 2015 and 2019 had been roundly rejected by the electorate, securing only one seat from the total number of votes polled island wide. The President’s move provided some stability within a government in disarray since early April, as Wickremesinghe formed a new Cabinet with the support of the Rajapaksa party, the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (Peoples’ Front) and crossovers from the opposition. The perception, encouraged by business interests and liberal civil society, that Wickremesinghe with his pro-private sector, pro-western, cosmopolitan orientation is the best captain in stormy seas – along with anxiety over violence and “extremism” post-9 May – did contribute to fallback in middle-class participation in the protests.

However, the crippling shortages of fuel and the deterioration of economic and social life maintained the anger within the citizens’ movement now known as the Aragalaya (meaning ‘struggle’ in the Sinhala language).

To redouble the demand for ‘Gota’ now joined by ‘Ranil’ to “go home”, 9 July was decided by the groups at #GotaGoGama for a mass protest targeting the president’s office (besieged but not occupied) and his nearby official residence (where he had been bunkered under heavy guard since evacuation from his private residence in March). This turned out to be the single largest mobilization of the citizens’ movement so far in 2022. Against the odds and overcoming many obstacles in their way, people from popular classes overwhelmed the armed might of the military and police to spectacularly capture the Presidential Secretariat and the President’s House. Spontaneously, others massed outside the Prime Minister’s official residence, unoccupied by Ranil Wickremesinghe but under continuous protest by people camped outside it (#NoDealGama/#RanilGoGama), finally taking possession late that night. Finally, after months of protests, Gotabaya Rajapaksa who had taken refuge onboard a naval craft, announced his resignation, before taking flight for the Maldives and later Singapore.

Throughout 9 July, Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe resisted the demand from protestors for his resignation, claiming he was needed until the formation of an all-party government. This incensed those who had expected him to depart along with the president with whom he had tied-up politically. Crowds spontaneously formed outside Wickremesinghe’s private residence (which he had vacated in advance). They were beaten back by armed police, who also assaulted journalists filming this violence. As word of this attack grew, larger numbers arrived. In a bizarre twist, and under the watch of the security forces, his home was set on fire. Still, the prime minister (by now Acting President) resisted handing in his resignation. This prompted militant demonstrations on 13 July outside his office, which fell to protestors despite tear gas and water cannon assault. In the subsequent week, the state premises that were occupied on July 9 and 13 were voluntarily vacated by protestors.

ET: Do the different ethnic and religious communities across Sri Lanka participate in the protests in the same way?

BS: The Aragalaya is largely a movement within the majority Sinhalese nation, and of cities and towns in the Sinhala-speaking south of the island. The minority Tamil nation, particularly in the Tamil-speaking north and east, held back from actively participating in the movement. Small delegations from those areas did visit #GotaGoGama to express their solidarity, while raising their own demands for post-war truth and accountability, against militarization of their traditional homeland, and for return of their lands under military occupation. The ethno-religious Muslim minority, at the receiving end of violence and Islamophobia since the end of the war in 2009 and following the Easter Sunday terrorist bombings in 2019, was initially wary but this changed over the fasting month in April. Hill Country Tamils and those of north-eastern origin but domiciled in the south did participate in the protests.

Ethnic minority communities had mixed sentiments towards the movement, as did the Sinhalese but for different reasons. As the former president is a representative of Sinhala Buddhist chauvinism, some perceived the Aragalaya as a belated mea culpa from his heartland, except still unacknowledging of the injustices to minorities in a racist state. Others feared that their overt association with the protests would make them vulnerable to state surveillance and expose them to reprisals. No movement in and of itself, can erase the contradictions and fractures within society, especially when these are side-stepped at best and unseen at worst. Nevertheless, some within the Aragalaya did revisit an uncomfortable past, including historic discrimination against minorities, and the crimes against humanity committed on Tamils in 2009.

ET: Is it correct to say that the causes of the current crisis are the sum of the effects of the neoliberal capitalist model recommended by the IMF/World Bank and desired by Sri Lankan big capital, converging in the last two years with the dramatic fall in tourist revenues coupled with the increase in the price of fuel and food imports? Please recall for us when the big neoliberal turn was taken, and by what kind of government?

BS: Loyalists of the Rajapaksas within the Parliament and its apparatchiks in state institutions, Sinhalese nationalist civil society and pro-regime media, locate this crisis in what is external to the domestic economy and therefore beyond the control of the regime: the COVID-19 pandemic induced disruptions to global and domestic supply chains impacting production and circulation; the collapse of inward tourism over 2020-2021; Russia’s war on Ukraine (both countries being prime markets for Ceylon tea and recently countries of origin for tourists); and global price spirals in fuel (petrol, diesel, LP gas) and food (wheat, maize, milk powder, sugar) and fertilisers (urea). This is of course to absolve former President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, his advisors, and his family members in government (older sibling Mahinda was Prime Minister up to 9 May 2022 and younger sibling Basil was Finance Minister up to 4 April 2022), from responsibility for this disaster.

Critics of the Rajapaksas drawn from the political opposition, think-tanks and economists, and liberal civil society, attribute the crisis to rash, ‘populist’ actions following 2019’s presidential election, principally reforms to direct tax thresholds and value added tax that halved receipts; the ‘organic only’ ban on chemical inputs in agriculture that damaged rice and tea harvests and herald a looming famine; money-printing (as endorsed by modern monetary theory) to finance government expenditure that fed inflation; the drastic fall in migrant workers’ remittances through official channels (as informal channels offered a more attractive dollar to rupee conversion rate); and refusal to enter into an International Monetary Fund macro-economic programme, accompanied by debt restructuring. This narrative squarely faults the regime, while acquitting the economic model of any part in the tragedy.

Therefore, mainstream, or dominant explanations for Sri Lanka’s troubles blame conjunctural factors. There is a third point of view: the issues above are symptomatic and not causative of the crisis. In other words, the origins of our turmoil are structural. In Sri Lanka, the chickens farmed by neoliberal capitalism came home to roost in 2022. Every manifestation of the current crisis, and every failed response, is an outcome of these hegemonic ideas packaged in policies, processes, and mechanisms.5

The 1977 election triumph of the United National Party (UNP), the grand old party of the right in Sri Lanka led by J. R. Jayewardene (uncle of Ranil Wickremesinghe), was a decisive break from the dirigiste policies of the past. The UNP ushered the first wave of pro-market liberalization reforms allegedly to overcome the failings of the ‘closed economy’ after 1970, and to imitate Singapore’s path to prosperity. This was 10-15 years before the rest of South Asia would follow suit. These reforms it should be noted were not an outcome of an IMF-World Bank loan (which followed), but rather the vision of a new leadership team with new ideas in the UNP in concert with outward-looking sectors of the domestic capitalist class. Of course, the progress of what we now know as the ‘Washington Consensus’ or ‘neoliberalism’, did not conform to textbook theory: the political economy of Sri Lanka (as of any other social formation) stood in its way.

An internal war between the Sri Lankan state and Tamil separatists raged between 1983 and 2009 expanded the reach and social weight of the military. In between, there was an insurrection of Sinhalese youth against the state between 1987 and 1989 led by the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna, stemming from the dual political authoritarianism and economic liberalism of the UNP. Nevertheless, there was another neoliberal wave in the early 1990s, begun by the UNP but continued by its historic centre-left antagonist the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP). The most recent wave under the Rajapaksa-led SLFP was during the 2007-8 global financial crisis. So, there is continuity in the orientation and trajectory of capitalist development from the late 1970s up to the present, notwithstanding alterations in political regime.6

Trade, both import-export and domestic, was liberalized for entry of private capital. The withdrawal of the state undermined its capacity to regulate market prices, store and distribute food stocks. Cartels particularly in the milling and sale of rice and within the import sector grew stronger. Foreign capital was courted through establishment of export processing zones, generous tax holidays, and unrestricted capital flows, as well as repression of wages within export manufacturing in addition to the suppression of trade unions and labour rights. The service sector became the most significant in the economy, creating jobs without security and rights. Corporate taxation and the tax to GDP ratio is among the lowest in Asia. Indirect taxes which hurt the poor, contribute 82% of total tax income, underscoring the resistance of the rich to direct and progressive taxation. Small farmers lost their customary access to state land to agribusiness which benefited from bank loans and export incentives. Combined state allocations on health and education are less than the military budget, and adequate only to meet salaries and other recurrent expenditure.7

Export-oriented industrialization supplanted import-substituting industrialization, except that the exports are of low value addition ready-made-garments, while the imports are of raw materials, intermediate goods, and machinery, worsening the imbalance between import expenditure and export income. There was no effort to sustain industrial production for the home market, in cement, ceramics, paper, leather, textiles, fabricated steel, sugar, processing of fuel and lubricant oils, etc. These were not considered to be industries of comparative advantage for Sri Lanka, and anyway imports were cheaper and plentiful, with quicker profit for less effort. This deindustrialized the island economy, destroying local capacity, skills as well as employment, and intensifying dependence on the vagaries of the world market.

Meanwhile, the main agricultural export of tea (and to a lesser extent rubber) continued to be important, except that the terms of trade consistently favour exporters of manufactures over primary commodities. Even major export items such as garments and tea substantially rely on imported inputs. Tourism became more significant as a source of foreign exchange, although never on a mass scale nor surpassing apparel and tea, but again requires large infusions of imports of construction materials, fittings and fixtures, and food and beverages, with added vulnerability to shocks as experienced during COVID-19.

The single largest source of foreign exchange, however, has been remittances from workers in domestic labour in West Asia. The point to underline is that the three top contributors to foreign earnings – labour migration, apparel, and tea – all derive from women’s labour in low-waged jobs.

What is the balance sheet of Sri Lanka’s “open economy” after more than 40 years?8 It has been to increase dependence on world trade (exports and imports), foreign and private capital, borrowing to finance mega-scale and often commercially unviable, infrastructure projects, as well as to bridge the yawning gap between income and expenditure. Sri Lanka’s indebtedness has grown exponentially to $51-billion (US), relative to a small economy of $80-billion (US). The financialization of the economy diverts investment from production, also driving household indebtedness through microcredit institutions. Low-skilled labour migration especially to the Middle East is a mainstay of many poor households. State capacity to regulate prices of essential commodities and services and protect basic consumption, jobs and incomes in society, and access to health and education especially in times of heightened distress such as at present, is degraded. Meanwhile inequalities of income and wealth have exploded grotesquely, as has the informalization of employment creating greater insecurity for wage-labourers and their households. Class consciousness has eroded in the organized working class; and the decline of the left as an ideological, political, and organizational reference appears inexorable.9

ET: Are there any similarities between Sri Lanka in 2022 and uprisings in Egypt and Tunisia (2011) and Lebanon (2019)?

BS: After the 31 March protest, the government described the citizens movement as replicating the ‘Arab Spring’. This was intended as a slur. The inference was that the protestors by aiming to overthrow the president, were agents of upheaval, instability, and chaos; perhaps even opening the way for intervention and destabilization by foreign powers, and not to forget the trope of Islamophobia to create a wedge among protestors. However, within the citizens’ movement there was no comparison or reference to the people’s uprisings beginning in 2010 in Tunisia, Egypt and elsewhere in the Middle East and North Africa. There is no evidence even among organizers within the Aragalaya, of close study of those movements.

What maybe common between Sri Lanka in 2022 and the ‘Arab Spring’ is that economic crisis, lack of opportunities and daily hardships due to scarcities of essential goods, provoked young people into taking to the streets; grand corruption was identified as reason for the failure of governments to provide a decent standard of living to all; and the remedy was thought to be greater democratization of the political system and state structure. What is starkly different, unlike Tunisia and Egypt, is the abstentionism in Sri Lanka of the working class in workplaces and through its organizations within the current movement, excepting delegations of trade union leaders to #GotaGoGamas in Colombo and elsewhere, and the thunderclaps of the 28 April hartal (‘stay-away’) and 6 May general strike. A happier difference from Egypt is the absence to date of a military grab for power in Sri Lanka.

Among right-wing commentators in 2021, there were uncomplimentary references to Lebanon’s crisis as holding a mirror in which Sri Lanka’s future is foretold. There has been no discussion of the Lebanese ’17 October uprising’ within the citizens’ movement in Sri Lanka. Insularity runs deep on this island, including in its left and trade unions. What may be shared in the uprisings in both countries is the conscious attempt to rise above ethno-religious divides, identifying as one people with common economic issues and a common enemy in the government, and rejecting the executive as well as the legislature. In both places their respective Central Bank governors were seen as shouldering responsibility for the crisis, even if in Sri Lanka the banking system is stable for now. Perhaps another commonality between the two movements is that they succeed in bringing down governments, but not yet in making one of their own choosing.

ET: Is there an awareness of the importance of the debt issue among a significant sector of mobilized people? There were huge mobilizations against the IMF in Argentina also on 9 July 2022. Is there a significant sector that is convinced that there should not be a new agreement with the IMF? What should be done with the debt payments and with the IMF? What are your proposals for emergency measures to face the crisis in Sri Lanka?

BS: Whereas in Argentina, people take to the streets opposed to the IMF, in Sri Lanka it is more likely that people would demonstrate demanding an IMF intervention. Truly there cannot be another country where an IMF agreement is more desired than Sri Lanka. Of course, this infatuation is based on immediate desperation on the one hand, and innocence of austerity conditions on the other. There is no ongoing IMF programme to be familiar with its pain and destitution of the poor. The most recent (16th since the first agreement in 1965) was in 2016 and not completed, but still being repaid over 2021. In the current crisis, it has been drummed into society that with all doors to fresh loans closed to it, there is no alternative for Sri Lanka than to look to the lender of last resort.

The lie that has been fed is that the silver bullet to kill the crisis is the IMF. It is not explained that the IMF itself is unlikely to lend more than $3-billion (US) through its Extended Fund Facility, and that too in installments over 4 years. This sum does not amount to more than the cost of six months of petroleum products. It is also under half of what Sri Lanka was due to pay in debt service in 2022 alone. While it is assumed that IMF funds will support urgent imports, Sri Lanka will be expected by the IMF to resume servicing its debt, and to prioritize its revenue for this purpose. Above all, an IMF programme does not fix the reasons why Sri Lanka was caught in the debt trap, nor how with its current economic structure and insertion into the global economy it can ever achieve a balance of payments surplus, to avoid new borrowings.

There has been no resistance or alternative to an IMF programme from a stupefied left, ranging from the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna to social movement activists. “We should take the money but reject austerity or make conditionalities human rights compliant”, say some optimists. “The IMF has changed from the 1980s, it is more relaxed on public spending and even supports a social safety net for the vulnerable”, insist others. “We are already experiencing austerity, what can the IMF make worse?”, bark a few. “It was a mistake to default on the debt” (which Sri Lanka did in May 2022) declare others. “We need an IMF agreement so that Sri Lanka’s risk rating improves to borrow again from bilateral and multilateral agencies, and the bond market.”

Some private sector trade unions have rightly demanded that the government should be transparent in the negotiation process with the IMF and release the draft staff-level agreement to the public. However, up to now, beyond terse media releases on the process, there is no technical information on the outlines of the proposed programme.

It remains to be seen whether once an IMF agreement is rolled out, there will be a radicalization of the movement around likely conditionalities such as increased taxes on fuel and food and tariffs on electricity, water and other public services, public sector pay freeze and downsizing, ‘fiscal consolidation’ through reductions in spending on health, education and social services, labour market deregulation including on working hours, ‘hire and fire’, and privatization of state-owned-enterprises. The right has smartly found its opportunities to advance the neoliberal project in this crisis, taking advantage of fuel shortages and power cuts, to promote privatization of the state-owned Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (CPC) and Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB). Sinhalese nationalists may go into xenophobic opposition against an IMF programme, if only for the purpose of differentiating themselves from President Ranil Wickremesinghe before the electorate. Often in relation to anti-privatization campaigns involving Indian capital, and the US-backed Millennium Challenge Corporation agreement (MCC), left-wing trade unions and organizations have made opportunistic alliances with Sinhalese nationalists, in the guise of “anti-imperialism.”

So far, the question of debt has not been taken up within the citizens’ movement. Sri Lanka is already in default. This has interrupted a fringe discussion cutting across right and left, as to whether the government ought to unilaterally suspend debt servicing to prioritize foreign reserves for essential goods especially medicines. Sri Lanka will probably not resume debt repayments until sometime in 2023. The government has hired Lazard and Clifford Chance as its financial and legal advisors respectively to advise on restructuring the external debt. This year, there are murmurs around odious and illegitimate debts in relation to the Rajapaksas. Some solitary voices call for an audit of the debt especially the International Sovereign Bonds (ISBs). However, this has yet to become a demand of political parties or social movements.

A brief overview of the composition of Sri Lanka’s foreign debt may be of relevance at this point. The largest chunk of foreign debt around 47% comprise ISBs which are thought to be held by BlackRock, Allianz, UBS, HSBC, JPMorgan Chase, and Prudential, and to a much lesser extent Sri Lankan commercial banks and other locals (rumoured to include parties close to the Rajapaksas). Bilateral creditors principally Japan, China and India, and others collectively account for 31%. Finally, multilateral creditors, the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank, account for 21%.

The Western and Indian narrative of a ‘Chinese debt trap’ is mala fide. Nevertheless, two points on Chinese loans should be made.10 Firstly, its actual proportion is closer to 20% than the Central Bank of Sri Lanka recorded 10%, as the official figure does not include lending to state-owned-enterprises (by the EXIM Bank of China and China Development Bank). Secondly, Chinese loans financed Rajapaksa-era mega-infrastructure and vanity projects which have not been to the benefit of the people, and whose costs were allegedly inflated by hefty ‘commissions’ to the former first family and connected parties. Therefore, these loans amongst others should be audited to determine whether the debts incurred are odious or illegitimate.

Aside from the ongoing debt default, there should be a moratorium on future servicing pending an audit (inclusive of domestic debt) and reorientation of the economy around the recovery of popular classes from this crisis. In addition to substantial ‘haircuts’ by private creditors, all illegitimate debts should be cancelled. Household indebtedness has also expanded during the crisis, as loans are taken for consumption needs, and to meet urgent expenses. There should be debt relief for households as well, supplemented by direct assistance for household needs and productive activities, to break the cycle of new loans to repay old loans.11

Some emergency or short-term measures that are urgently needed include the provision of a basket of essential foods to low-income households in urban, estate and rural areas, to protect them from starvation.12 This should not be based solely on the existing registry, but include those pushed into poverty through the crisis, and internal migrants such as export factory workers and others temporarily resident near their places of employment. In this process the public distribution system that was dismantled by the ‘open economy’ should be rebuilt under community control. Farmers and fishers should be prioritized in supply of diesel and kerosene to be able to resume production and distribution. School and public transport should be privileged over private vehicles in the rationing and supply of fuel. Employers should take responsibility for transport of workers.

The tax burden on the poor must be removed, with value-added-taxes increased on consumption by the rich. An employment guarantee scheme to assure a minimum number of days of waged work must be rolled out in urban, rural and estate communities. The super-profits made by banks, finance companies, and other sectors, during the pandemic must be subject to higher taxes. The military budget must be halved, with those allocations channelled into health (including nutritional supplements for mothers and infants) and education (including fresh milk and mid-day meal for students). There should be a moratorium on the loans of micro and small enterprises and reductions in the interest rate for bank credit, to enable them to survive while sustaining production and employment. Community-owned and managed credit and distribution mechanisms including cooperatives should be assisted to prioritize the needs of working people and especially women.

ET: With the appointment of the new president and the use of repression against the demonstrators, clearly the regime is not making serious concessions, what can happen?

BS: While the ouster of the former president Gotabaya Rajapaksa and the expulsion of his family from government is a victory for the citizens’ movement, the election of Ranil Wickremesinghe as the president, is a serious setback.13 This has for the moment stabilized the political order that safeguards the Rajapaksa family, its political party, and the status quo, against which citizens have been protesting. This ‘selection’ of the new president has the blessings of big business, the middle class and liberal opinion. This new situation has substantially demobilised the citizens’ movement and is systematically demonizing it now. The Aragalaya’s demand was for an interim all-party government led by a caretaker president and prime minister to institute reforms diluting the executive powers of the presidency and providing economic relief and stability pending an early general election. Radicals within it also demanded a People’s Council, as an extension of participatory democracy, to represent the interests of citizens as a counterpart to the parliament. However, the Aragalaya has been checkmated by the scheming of the new president backed by the rotten majority in parliament. The aim of those in government is to string out the term of this parliament until 2024, protecting the parliamentarians of the Rajapaksa regime from criminal investigations, and possible loss of their electorates.

Within hours of Wickremesinghe’s oath-taking as president on 21st July, he unleashed the military on the ‘GotaGoGama’ agitation site in Colombo, assaulting protestors and destroying some tents and spaces. Since then, the repression has intensified and is unrelenting, while emergency law is in force. Around 100 people including those most visible as influencers or spokespersons during the movement have been abducted or arrested by the police for various offences relating to their entry into or occupation of public buildings or just participation in peaceful protests. Journalists and media organizations that provided sympathetic coverage of the protests are being harassed. Trade unionists who amplified the demands of the Aragalaya are being arrested at this time. The police are trying to remove the remaining protestors at Galle Face Green, thinking this will deflate the movement.

There is a concerted campaign on social and mainstream media to smear the protestors as variously ‘fascists’ or ‘anarchists’, funded by Western governments and NGOs and even the Tamil diaspora to effect regime change. There were solidarity protests across the North and East (Jaffna, Mannar and Batticaloa) on 29 July of civil society organizations, women’s groups, Christian clergy, human rights defenders, and others from the Tamil and Muslim communities, calling for the release of all those detained and an end to the repression. There have been solidarity actions in Sri Lankan communities overseas. These must continue and have the support of the left and labour movement organizations in those countries too.

This struggle is unfinished and is presently experiencing a serious setback. But it is undoubtedly the most uplifting and hopeful social struggle in Sri Lanka of the 21st century. All those everywhere inspired by the people’s uprising of 2022 must now rise in its defence. Aragalayata Jayawewa/Poraattathukku Vetri/Victory to the Struggle! •

This interview first published on the CADTM website.

Endnotes

- B. Skanthakumar (2022). “Sri Lanka’s Crisis is Endgame for Rajapaksas,” International Viewpoint (Paris), 13 July 2022.

- B. Skanthakumar (2022). “Weeks when decades happen,” Polity (Colombo), Vol. 10 (Issue 1): 3-4.

- Meera Srinivasan (2022). “Janatha Aragalaya | The movement that booted out the Rajapaksas,” The Hindu (India), 17 July 2022.

- Meera Srinivasan (2022). “‘Occupy Galle Face’: A tent city of resistance beside Colombo’s seat of power,” The Hindu (India), 12 April 2022.

- Devaka Gunawardena and Ahilan Kadirgamar (2022). “Economic collapse and the post-IMF crisis,” Daily FT (Colombo), 1 April 2022.

- B. Skanthakumar (2013). “Growth with Inequality: The Political Economy of Neoliberalism in Sri Lanka,” Law & Society Trust Review (Colombo), Vol. 24 (Issue 310), August 2013: 1-31.

- B. Skanthakumar (2022). “Budget 2022: Brace for Austerity,” Polity (Colombo), Vol. 10 (Issue 1): 50-57 at p. 50.

- B. Skanthakumar (2017). “Accounting for 40 years of market reforms,” Daily FT (Colombo), 11 October 2017.

- B. Skanthakumar (2015). “Labour’s Lost Agency: What happened to the labour movement in Sri Lanka,” Himal Southasian (Kathmandu), Vol. 28, No. 1: 12-34.

- Umesh Moramudali and Thilina Panduwawala (2022). “From project financing to debt restructuring: China’s role in Sri Lanka’s debt situation,” Daily FT (Colombo), 17 June 2022; Umesh Moramudali (2022). “The Sri Lankan Foreign Debt Problem.” Watchdog, 4 March 2022; Verité Research (2021). Navigating Sri Lanka’s Debt: Better reporting can help – a case study on China Debt. Colombo: Verité Research.

- Amali Wedagedara and Ermiza Tegal (2020). “Tackle the household debt pandemic: Cancel debt! Create common credit,” Daily FT (Colombo), 29 May 2020.

- Feminist Collective for Economic Justice (2022). “Sri Lanka’s Economic Crisis: a feminist response to the unfolding humanitarian crisis,” Polity Online, 9 April 2022.

- B. Skanthakumar (2022). “In Sri Lanka’s Crisis, a new president and old problems,” Labour Hub (London), 21 July 2022.