Precarity and Green Unionism

In a real sense, under capitalism, all workers are precarious, meaning that they can be downsized, replaced, deskilled, outsourced, and so on. It’s simply a matter of degree. The latest peak in precarity is “gig work,” which has always existed; the names simply keep changing, but the concept is the same.

Unions represent a check against precarity, though this occurs on a graduated scale. The stronger the union, the less the workers’ precarity. Union strength manifests in various ways: It can result from a well-organized, international, militant, democratic union (ideal, but rare, with few real-world examples, such as the International Longshore Workers Union and the Industrial Workers of the World, of course). More often than not, union strength is a result of a concentration of elite craft workers in skilled-trades unions. That situation represents a strong guard against precarity, but only for workers in the union, so that solidarity is limited.

Other checks against precarity include high demand for skilled workers in rare supply, high demand for hard-to-replace workers (such as those who require skilled credentials, like teachers or transport workers), or tight labor markets (which exist in our semi-post Covid-19 world due to a combination of factors).

Back to the Basics: Class Struggle

This is nothing more than class struggle 101, as expertly phrased by Karl Marx and others.

There are new forms of precarity emerging due to the climate catastrophe brought on by capitalism. Workers find themselves facing new health and safety hazards and threats to their working environment.

Some examples include:

- Increased risk of smoke inhalation due to increased and more severe wildfire activity.

- Increased exposure to longer and more severe heat waves, directly resulting from global heating; for example IWW workers at Voodoo Doughnuts in Portland, Oregon, were fired for striking due to extreme heat in June (the National Labor Relations Board ultimately ruled in favor of the workers).

- Loss of work time due to severe snow storms, severe hurricanes, or flooding (and some workers have lost their jobs due to inability to transport themselves to work through such conditions).

- Even Covid-19 is essentially related to climate (as Ian Angus et. al. have pointed out in their excellent analyses linking climate and metabolic rift to increased pandemics1), and we know that Covid-19 raised precarity to a whole new, unforeseen scale. The struggles related to Covid have sparked a wave of increased union militancy.

Many workers, even in unionized workplaces, lack climate- or environment-related protections, and only through widespread worker organizing have any basic workplace rights related to these hazards emerged. (The good news is that this has helped further erode support for neoliberal capitalism, though much of that dissatisfaction has been channeled into a social-democratic capitalist reformism. It still represents an opportunity for green syndicalists, ecosocialists, and others to organize genuinely revolutionary anti-capitalist alternatives, and the receptiveness to those is increasing.)

A transition to a cleaner energy system is an essential part of averting the worst aspects of climate disaster (though we are in for a world of hurt, even under the best scenarios). This won’t be easy or uncomplicated. Skilled union workers in building trades, many of which are heavily intertwined with the extractivist, fossil fuel, and growth-for-growth’s-sake supply chains, perceive the needed energy transition as a form of precarity they wish to avoid. This is largely based on exaggerations made by the capitalist class, particularly those directly profiting from the aforementioned supply chains.

It doesn’t help matters that the vast majority of the “green” jobs have a higher degree of precarity than those in fossil-fuel-based industries as well as lower standards of working conditions and pay. That is why green unionists, ecosocialists, and climate justice activists alike call for a just transition for the affected workers. One of the key demands of this transition is that these workers are not subjected to greater precarity!

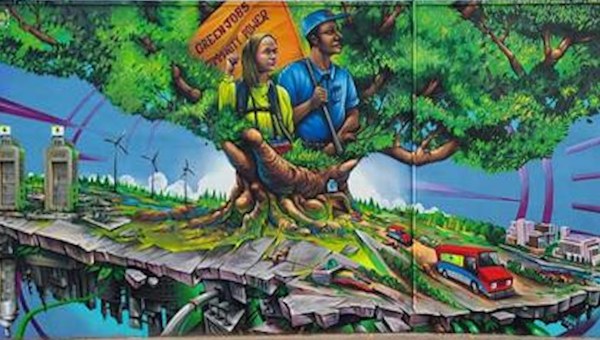

This is what could be called green unionism. Green unionism is an essential strategy for addressing climate catastrophe as well as the ongoing challenge of precarity, a persistent feature of capitalism that the bosses will almost certainly try to continue to implement (often as a form of disaster capitalism) as the climate catastrophe worsens.

Is Green Unionism Even Possible?

It’s not unheard of for skilled union workers facing threats of increased precarity to propose radical alternatives to avoid it and at the same time provide a green transition. As early as 1976, workers who made weapons and instruments of war in the United Kingdom at Lucas Aerospace, when faced with downsizing, proposed making socially useful green technology instead! Meanwhile, in Australia, the left-communist influenced Builders Labourers Federation engaged in a series of strikes to oppose building developments that they deemed “anti-environmental.” This series of strikes became known as the Australian Green Bans. Almost simultaneously, Italian workers in Porto Marghera proposed even more revolutionary demands: the abolition of all “noxious” (ecologically destructive) work entirely!2 Strongly influenced by the autonomist Marxist movement of the time, they called for nothing less than the absolute abolition of the entire factory system (as opposed to self-managed creative work, organized by the working class autonomously from capitalism, as a way to run society).

These green syndicalist movements, unfortunately, were isolated and mostly ignored or even denounced by much of the “official” left, including most Communist movements, plus they arose as Keynesian social democracy began to decline in the early 1970s. Lacking both a large enough scale and favorable objective conditions, these movements quickly faded and were largely forgotten by time, especially as neoliberalism was ascendant.

It wasn’t until the 1990s that pockets of green unionism arose again, in two particular instances: One was Tony Mazzochi of the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers Union (now merged with the United Steelworkers) which represented workers in many “polluting” industries, such as oil refining and nuclear power. Mazzochi argued that “there is a superfund for dirt, therefore, there should be a superfund for workers.” It was he who essentially devised the concept of “just transition.”

Meanwhile, in northwestern California, a one-time union member turned Earth First! activist (and carpenter), Judi Bari, introduced class-struggle environmentalism into the budding Earth First! movement. Under her influence, the Earth First! attempts to blockade clear-cut capitalist timber extraction had a pro-worker component to them.

Both Mazzochi and Bari were organizing against the threat of precarity. However, the times weren’t in their favor, being at the height of the neoliberal era, right after the “fall of communism” in 1989.

Ecological and climate conditions have worsened greatly since then, but the strength of grassroots movements has grown substantially and the popular opinion among the working class is much more favorable now to anti-capitalist alternatives. And, ironically, climate catastrophe and Covid-19-induced conditions – which brought on the “Striketober” – have made the proverbial soil much riper for a growing and deepening green unionism movement. This is manifest in the growing support among unions and union workers for addressing climate change, including support for the concept of a Green New Deal (loaded and complicated though that may be). In fact, support for the Green New Deal consistently polls higher among union workers than it does among the general public, in spite of the alleged (and greatly exaggerated) “opposition” from organized labor. This support includes some workers employed directly in the greenhouse gas emitting industries. For example, some of the strongest support for Robert Pollin’s California Climate Jobs Plan, which is essentially a proposal for “shovel ready Green New Deal programs for California,” comes from the United Steelworkers (Tony Mazzochi’s old union!).

Ultimately, we will need a complex combination of ecosocialism, an overall degrowth to the economy, but a growth of green jobs, especially in the short term. In fact, so many new jobs must be created that the recent “Striketober” could be dwarfed, as the demand for skilled work will increase so much the capitalists will be unable to replace striking workers. And forget about the “robot apocalypse”; like precarity, automation and deskilling have existed from the beginning of capitalism and are nothing new. Several knowledgeable, veteran class-struggle union members, including Kim Moody, have convincingly shown that the “robot apocalypse” is nothing more than doom porn. If anything, there are more jobs in existence now than ever before, and that won’t change much. What matters is – and you may have guessed it – the degree of precarity the workers in these jobs experience.

None of this should be taken to suggest that we will win the class struggle automatically. Nothing is guaranteed, and we cannot let the capitalist class or random chance carry out our organizing work for us. It is essential that as ecosocialists, climate justice activists, union members, and others, we dedicate our efforts to organizing at the point of production. One way to do this is through what the IWW (inspired by Alice and Staughton Lynd) calls Solidarity Unionism: the winning of gains through workplace organizing whether or not legally represented by a union or covered under a recognized union contract. That is how the labor movement arose in the first place, and there is no reason to think that the requirements are appreciably different now. If the mainstream business-union bureaucrats, such as the leadership of the building trades unions, drag their feet or stand in our way, we must out-organize them, even in spite of them. And if, at any point, unions engage in the sort of aforementioned green syndicalist efforts that arose in the 1970s, we must ensure we, the working class, have their backs.

Climate catastrophe is the ultimate form of precarity. There are no jobs on a doomed planet.

To paraphrase Karl Marx, workers of the world, unite! We have nothing to lose but our very existence! •

This article first published on the New Politics website.

Endnotes

- For example, “Ecosocialism or barbarism: an interview with Ian Angus,” Review of African Political Economy, March 24, 2020. Angus is the editor of the Climate and Capitalism website. Also see Neil Faulkner, “Covid, climate, and ‘dual metabolic rupture’,” The Ecologist, Feb. 1, 2021.

- The Political Committee of the Porto Marghera Workers and Lorenzo Feltrin, “Against Noxiousness (1971),” Viewpoint Magazine, April 1, 2021.