The Eighteen Percent Tory Majority: What Now for Education in Ontario?

There’s something happening here

But what it is ain’t exactly clear.

There’s something happening here. But it’s not Buffalo Springfield singing the song and it’s not 1967, another dire time in history – it’s now and it’s Ontario where we have elected the same right-wing government for the second time in a row. It doesn’t seem to matter that Doug Ford and his friends fiddled with local municipal elections and then made it much harder to fight back with Bill 254. It makes no difference that his government addressed the devastation in long-term care homes by throwing more money at companies profiting from their neglect. Cuts to health, social services, and education are not worrisome enough to keep this government from an increased mandate to do more of the same.

Our collective memory apparently doesn’t include things like jamming more kids into classes, kids who were already stressed out by the rudderless policies of governments over the years. It looks like it wasn’t too significant that school boards cut their budgets, that their buildings are falling apart, that they can’t support kids with special needs like the over 50,000 autistic young people on the waiting list for extra help. The incompetence of this government’s response to COVID-19 must have been no longer relevant when Doug Ford declared that it was time to get back to normal.

What is relevant is that this phenomenon of regressive politics was elected – chosen for what it represents despite its much-publicized defects. The Tories offered up a master class in neoliberal government: defund basic services early, degrade them so they don’t work, demonize progressive people like public servants who complain about it, and then “solve” the resulting problems by privatizing everything not nailed down. Given time and lacking coherent alternatives, people will withdraw. They won’t come out to vote; the distance between them and the landed political class is too great for there to be much point.

Lowest Voter Turnout

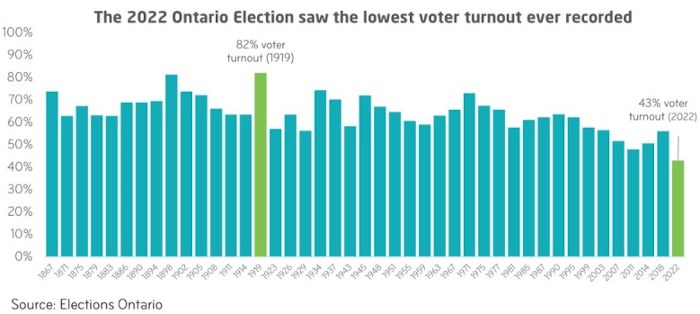

And that’s what happened this time. Voter turnout bled out to the lowest ever at 43.5 percent of those eligible. That’s about 4 ½ points lower than in 2011 when only 48 percent of those who could, voted. And look at the trend going back to the 1970s: 74% turnout in 1971, 66% in 1977; 63% in 1995 when the Harris Tories were elected. Then, through the early 2000s, the number of people showing up to vote dropped into the fifties, declining until 2018 when 57% of Ontario voters gave Doug Ford a massive majority of 76 seats with only 41 percent of the votes cast. That was a majority government chosen by only 23 percent of eligible voters.

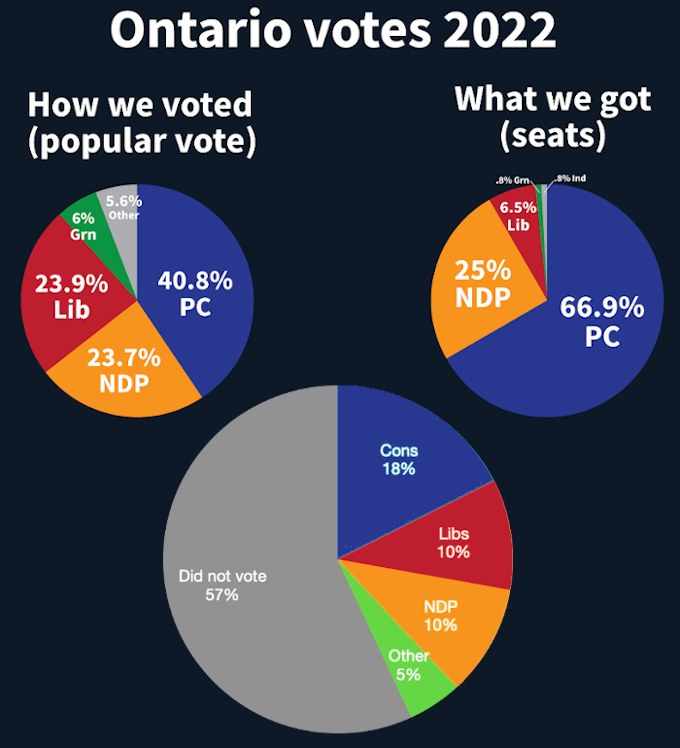

This time we have an even greater Ford plurality elected by about 18 percent of eligible voters. Naturally, Mr. Ford was unconcerned about this failure of democracy, remarking to CTV news: “I think it’s pretty clear the people gave us a mandate with 83 seats and we’re going to focus on our mandate. We travelled across this province for the last four to five weeks, setting a clear direction.” He ran a front-runner strategy – tightly scripted appearances, few questions, and a one-line ear worm: “Get it done.” Of course, the person heading up liberal democracy in Ontario needn’t give a thought to electoral reform, even with the deeply concerning results of the Liberal vs NDP, with both getting about the same popular vote while the former sits without party status and the latter forms the opposition. The NDP vote was more efficient; it counted where it mattered.

Why Aren’t People Voting?

It’s how the game works. “Game” also describes the way campaigns are covered by the media, with their eyes on strategy: who scored points with attacks on the opposing party of the moment, who blew their lead, who managed to stay out of trouble by saying as little as possible. It’s why there can be two columns in this morning’s Toronto Star about the unlikely merger of the Liberals and the NDP – yes, we’ve heard this before. It’s not anything to do with policy, as Martin Regg Cohn pointed out; it’s come down to a choice between “Esso and Petro-Can.” Whose brand – not coherent ideas – will hold? Of all the party leaders at the second election debate, only Green Party head Mike Schreiner had the nerve – maybe recklessness – to say that he would raise taxes for wealthier people to help pay for desperately needed programmes.

It’s a show that represents what Toronto Metropolitan University professor Bryan Evans explains is the recomposition of the state. Here, power is increasingly focused on the executive wing of government – in Ontario’s case, the Premier’s and ministers’ offices – with most of the policy work being done by staff, consulting groups, and law firms. Debates in the legislature are meaningless; elected representatives have little if any power.

For example, when the Ford government, back in 2018, decided to introduce “efficiencies” across the public sector – all the better to cut corporate taxes – it turned to the accounting firm Ernst and Young, which suggested ways to privatize parts of the school system and teach students, teachers, and parents to learn “resiliency” by cutting class sizes and getting rid of teachers. The result, says Professor Evans, is low voter turnout: “People don’t feel they’re heard. Voting is of no consequence.” The less equality you have in this recomposed state, the less likely you are to be engaged enough to vote.

York University professor Greg Albo describes how this centralization insulates bureaucracy from any kind of popular pressure and access, while offering a great opportunity to party members of all stripes to have access to the business community along with more consulting opportunities that it provides. It’s a perpetual motion machine that works well for left- and right-leaning parties alike. He doesn’t think that a change of leadership within the NDP is going to make a difference to its centralized, top-down bureaucracy. Bryan Evans adds that the party is “too entrenched in the office of the leader” and doesn’t give talented members much chance to develop a leadership base and skills. It’s a problem that affects liberal democracy overall in Canada, with rigid ruling structures, lack of mobilization, and inertia within parties and other organizations like unions that should be challenging them.

Jane-Finch Education Action (JFEA) stalwart Sam Tecle thinks the political parties are having an “existential crisis.” What leaders can emerge who can ask about the viability of a party even like the NDP, still struggling to develop strongholds in racialized communities? They need to do something in communities like Tecle’s to get across support for the people who didn’t show up to vote. He argues that even the Tories have done a better job of diversifying their membership, though they didn’t make candidates available to come and do interviews. Now elected with a larger mandate, Ford thinks they have a blank cheque to do as they please.

Fellow activist Anna Kay Brown attributes the low turnout to another kind of alienation. Jane and Finch residents have historically been disadvantaged in terms of housing, incomes, and services. Schools “are vastly under-resourced” and need to be redeveloped. Renters there, she says, don’t get much consideration from City Council. The many immigrants living in the area can’t yet vote. Candidates at all levels of government aren’t typically from the neighbourhood and are just seen as passing through on their way to higher office. Demolition of over 700 units in the Firgrove neighbourhood disrupted communities over the past few years, and some of the cement that ties people together is gone.

Brown fears that redevelopment and gentrification will only make things worse, as displaced residents will no longer be able to afford to live in the area. People are, by necessity, caught up in their own troubles, whether it be renters worried about rent hikes or people living in high rises worried about safety. She says, “We’re fighting in silos; we’re not getting anywhere- just chipping away at problems and a big chunk of cement is going back on.”

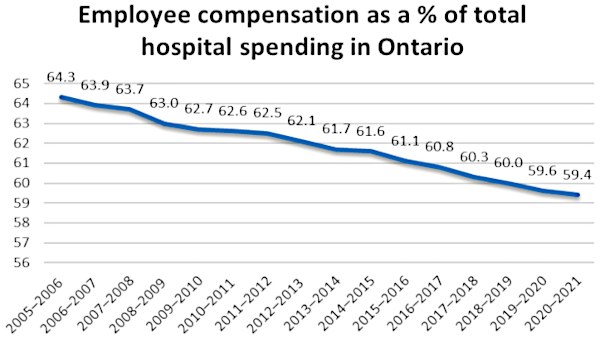

Dismantling Public Education with a Folksier Face

According to Ricardo Tranjan of Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA), once you set aside the different one-time funding programs to deal with COVID-19 in schools and child-care funding from the federal government, the bottom line is that school boards will get $800 less per student for the 2022-23 school year. Then there’s the issue of the $496-million the province “allowed” school boards to spend from their reserve funds to top up their COVID plans during the pandemic. The reserve is supposed to be used for special items like programmes for vulnerable students, nutrition programmes, and the like. There’s no plan for replenishing that money.

Instead, school boards are facing further deficits for the 2022-23 school year. For instance, Toronto’s school board’s is projected at $52.2-million. The Ottawa Carlton DSB expects to dip into its reserves to cover a $9-million deficit. Thames Valley DSB faces a $5.5-million shortfall.

As time-limited COVID funds came to an end with the election, school boards are starting to fire support workers. A report from City TV news has the TDSB planning to cut 300 lunchroom supervisors next year. Dufferin-Peel Catholic DSB is getting rid of 36 such staff, and Halton Catholic DSB will cut 22 ECE positions. Another 65 jobs will disappear across the Peterborough/Victoria/Northumberland/Clarington Catholic DSB.

With educator contracts expiring at the end of August – be wary. Expect the Ford government to offer a greater than 1 percent wage increase but keep it below the rate of inflation. That could be paired with austerity moves like cutting back on prep-time or pushing more online learning despite the disasters that accompanied it during COVID.

Class size will be another big issue, as the Tories have quietly cut back on funding for the 2021-22 school year, keeping class sizes higher as COVID numbers climbed. Also bear in mind that they planned to cut 10,000 teachers across the province in 2019 until contract negotiations with teachers brought that number down to 6,000. That’s still on the books to be done by 2024.

Look out for privatization. As Paul Bocking wrote last week, this is already happening. In 2020, the Ford government expanded the mandate of TVO/TFO to include developing and marketing e-learning courses with a “global development strategy”: for private schools and international markets. He adds that education technology may continue to threaten teachers’ autonomy as it shifts their work from teaching in classrooms to posting classes and activity modules online.

Also watch for more direct support for private education. Queen’s Park Briefing reported yesterday that Campaign Research, a firm partly owned by Tory advisor Nick Kouvalis, asked responders to agree or disagree with statements: “I should be able to pay for my own healthcare to get better service in Ontario” and “The government of Ontario should allow for more choice in education such as private and/or charter schools.” The Premier’s office says that it didn’t come from them. No comment yet from the Tories themselves.

Just keep in mind that back in early 2021 they offered no-strings-attached cash payments directly to parents – not to schools, which might have put them to good use. This totted up to $1.8-billion lost to the education budget. It’s a thin-edge-of-the wedge opening to a voucher system. Erika Shaker, director of Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA), thinks this is certainly one way the Tories will move. Look for voucher plans for parents who have to shell out money for tutors to make up for the ill-effects of remote and hybrid learning. A lot of potential Tory voters may welcome vouchers to use for privately operated cram schools and services to help their high school kids get ready for post-secondary schools.

Organizing – the Slow Way

So yes, this is a bit of a setback for those of us who thought the Ford government should be marched out of Queen’s Park and exiled somewhere along the route of Highway 413. Change just isn’t going to happen with political parties devoted mostly to their own survival or betterment. Don’t waste time blaming them – it’s in their nature.

It’s better to encourage activists locally and try to help them get together with others moving in the same direction. For instance, here in Toronto the ETFO local Elementary Teachers of Toronto (ETT) just elected a slate of progressive-education activists, led by Helen Victoros and Nigel Barriffe. They struggled for years with an entrenched group of “lifers” who just weren’t going to support the notion that unions have a role in preserving their communities, as well as looking after their members.

The Black Students for Success Committee (BSSC) down in Parkdale have organized at three area schools and managed to push a name change on one of them – formerly known as Queen Victoria PS. It’s now called Dr Rita Cox – Kina Minogok P.S., honouring Indigenous history and Black librarian Dr. Rita Cox who started the Black and Caribbean Heritage Collection at the Toronto Public Library. One of their members, Debbie King, is running for Ward 7 trustee in this Fall’s municipal elections.

Groups like Fix Our Schools (FOS) are working with Ontario Parents Action Network (OPAN). York Communities for Education and a slew of other groups across the province have come to the fore over the past few years. The big question is how to get all these different people to talk to one another. How do you get discussions going between Jane-Finch Education Action and Black Students Success Committees? It takes skilled organizers to do this, and the communication has to be well-developed between elections. As Erika Shaker points out, you can’t just drop the writ and expect to have articulate discussions. •

This article first published on the School Magazine website.