Unrelenting Neoliberalism: The Ontario Election and the Ford Government

Ontario is days away from a general election. For weeks, daily news coverage has been full of announcements and promises to make life better for Ontarians not only from the incumbent Progressive Conservative (OPC) Party led by Doug Ford, but also from the major opposition parties. Social media has also served as a battleground for the hearts and minds of Ontario’s voters, and has often provided a more equitable platform for smaller political parties in the province than the coverage offered by legacy media.

In advance of the writ drop, the government shifted into election mode, announcing policy it claimed will improve the rights and wages of some of the most precarious and lowest-paid workers in the province, as well as expand access to housing and daycare. Many of the government’s announcements were met with skepticism from unions, social movement leaders, and childcare activists who critiqued the government’s electioneering as ultimately insufficient in tackling the root issues plaguing Ontario.

Such late-term moves once again suggest the Ford government returned to its playbook of mixing conservative governance with populist gimmickry, such as its move to eliminate licence plate renewal fees and stickers, and its widely-publicized buck-a-beer campaign. When combined with the Keynesianism the government practiced during the pandemic crisis, such as providing tax relief for, and direct provisioning to, businesses, the question arises as to whether a larger policy orientation away from neoliberalism has infiltrated the Ontario state. Battles over the alleged death of the neoliberal moment of capitalism have been fought out for years in journals, the opinion sections of newspapers, across the pages of books, and on social media. This bears analysis across five policy areas of the Ontario state: fiscal policy; social policy; public sector management; state-private sector relations; and transportation infrastructure, and finds evidence of an unrelenting neoliberalism throughout the Conservative government of Ford, despite its periodic turns to state interventionism.

Neoliberalism in Ontario

Any discussion of neoliberalism in Ontario should begin with an examination of the historical and material conditions in which the government made its decisions. The roots of neoliberalism in Ontario reach back decades. According to Greg Albo, in Divided Province: Ontario Politics in the Age of Neoliberalism (2018: 12-34), as Ontario’s traditional branch-plant manufacturing base was increasingly battered by global industrial restructuring, new trade regimes, and recessions from the 1970s to the 1990s, provincial state policy moved away from direct social provisioning and toward developing co-operation between labour, business, and the government to improve the competitiveness of Ontario’s industry. A turn to austerity by way of tax increases and expenditure cuts began by 1992 under the New Democratic Party led by Bob Rae.

By 1995, the aggressive neoliberal project of axing public provisioning and tax cuts, along with bureaucratic rationalization and privatization entered its vanguard phase under the OPC Party led by Mike Harris and Ernie Eves. These processes, plus the wide scale adoption of privatization by way of public-private partnerships, largely continued under the Liberal Party of Dalton McGuinty and Kathleen Wynne – albeit with modest periodic investments into education and health – from 2003 to 2018. As a governance practice, neoliberalism in Ontario has largely taken the form of the provincial state intensifying market relations and individual competition throughout society, and remaking the Ontario bureaucracy in the form of the new public management focus on privatization, marketization and the like. Capitalist imperatives are at the centre of the Ontario state and its’ neoliberal policy regime.

Class Conflict Intensified

The 2018-22 period was particularly difficult for Ontario’s working class. A number of defensive strikes driven by a falling standard of living amidst high rates of inflation broke out across the province, and crackdowns on homeless people intensified as their numbers grew. The simplest measure of unemployment, despite temporary ups and down over the past four years and much larger numbers of unemployed reserves by other measures, remained essentially unchanged going into the election – moving from 5.9 per cent in June 2018 when the OPCs were elected to 5.4 per cent in April 2022. The poorest people in Ontario, meanwhile, were again abandoned by the province. In 2021, after homeless encampments in Toronto were destroyed and people arrested by police, Ford, a former Toronto city councillor, said he had no solutions for people who cannot find housing but told them they “can’t live in public parks.”

The neoliberal policies of the Ford regime that have unfolded during the COVID-19 pandemic have been characterized by integral ties between the capitalist class and the Ontario state to maintain, and even strengthen, class rule. Pandemic neoliberalism, to use a term that has gained some currency, has had to manage accumulation keeping some sectors open and by repeatedly closing and re-opening others across multiple waves of the virus. When pandemic-related deaths and case numbers in publicly-funded hospitals exceeded what even the ruling class could tolerate, lockdowns followed, with the Ford government pushed and prodded by public fears and demands from public health officials. Millions of workers in Ontario faced not only declining real wages, with the provincial government doing next to nothing to support workers with emergency wage supports coming largely from the federal government. Across the pandemic, workers have found themselves only a few hundred dollars away from financial ruin, with many reliant on emergency loans and credit to pay off their bills. The governance of the pandemic in Ontario has not broken from neoliberalism in Ontario, and it is pure fantasy to suggest, as some have, of a ‘return of the state’ in Ontario public policy. Indeed, the last four years of state policy under Ford further substantiates the perceptions that neoliberalism is alive and well in Ontario.

Fiscal Policy

After a brief period of relative stability following the June 2018 election, Ontario’s state finances were substantially impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. In October 2020, the Financial Accountability Office projected billions of dollars in revenue lost from the provincial corporations tax, personal income tax, and sales tax as businesses were shuttered during lockdowns and the unemployment rate skyrocketed at one point to nearly 14 per cent. Ontario’s Corporations Tax rate has not been changed since the Liberal Party gradually reduced it from 14 per cent in 2010 to 11.5 per cent on July 1, 2011 – making it one of the lowest general corporate rates in Canada. However, the government’s response to the economic and social crisis of the pandemic was largely centred on delivering tax relief to corporations through exemptions and subsidies.

Additionally, the government’s plan for several years to maintain its spending obligations and balance the $13.5-billion provincial deficit was to count on economic growth in order to avoid tax increases and service cuts. That approach was critiqued by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives as not accounting for inflationary pressures or the need to spend more on healthcare as the province’s population ages. Ontario’s 2022 budget projected the province will experience nominal Gross Domestic Product growth into 2025, but also that GDP growth will be slower each year, from an increase of 6.7 per cent in 2022, to 4.1 per cent by 2025. Increases in employment growth are also expected to slow from a projected 3.9 per cent in 2022, to 1.2 per cent in 2025. The province expects revenues to climb until at least 2025. Going into the election, the government’s revenue projections appeared to confirm its faith in projected nominal GDP increases and existing federal transfer, with tax increases left to the side. To that end, the OPC’s election budget promised $198.6-billion in spending, including $75.8-billion on health, $32.4-billion on education, $18.3-billion on children’s and social services; and a 10-year capital investment plan worth $158.8-billion that would pump money into highways, hospitals and other infrastructure.

Social Policy

Despite the election-timed promises contained in the 2022 budget, the government continued to produce neoliberal austerity by way of underfunding social programs. Austerity is a decades-long agenda in neoliberal Ontario and data produced by the Financial Accountability Office reveal the province has been among the lowest subnational state spenders on health in Canada since 2008, and at the bottom in terms of per capita hospital beds, nursing levels and other measures of provisioning.

That agenda, of keeping per capita programme spending in Ontario in the bottom rungs compared to other Canadian provinces, continued apace during the Conservatives time in office. In 2020-21, Ontario was last in per capita spending ($11,794) by all Canadian provinces on government programs. As an example, between April 1 and December 31, 2021, the government spent $119.9-billion – $5.5-billion less than planned. Many state portfolios including health, primary and secondary education, children’s and social services, and post-secondary education spent less than planned during that period – only spending on justice (which includes provincial policing, the province’s court system and tribunals, and corrections), was higher than planned, according to the Financial Accountability Office.

Neoliberal austerity can perhaps be most transparently observed in how the Ford government funded Ontario Works and the Ontario Disability Support Program. Both programs have been frozen since receiving 1.5 per cent increases in 2018, when the OPC Party ended the provincial basic income pilot project and cancelled a 3 per cent annual increase for welfare and disability assistance promised by the then-governing Liberal Party. In 2021, the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty requested a meeting with Minister of Families, Children, and Social Development Merrilee Fullerton to discuss the programs, describing them as “woefully inadequate” and at the root of poverty in this province.” In spite of these pleas, neither program was increased in the 2022 budget.

Ontario’s education system also took a hit going into the election. Despite earlier projections for $31.56-billion in base education funding (not including teachers’ pensions or time-limited pandemic-related funding), the province announced in its 2022 budget it was on track to spend only $29.5-billion – a $1.3-billion shortfall. When accounting for the gap in the 2022 budget, the government downloaded blame for the lower education expenditures onto schools themselves, noting a collapse in non-government revenue from activities such as fundraising, the renting of school facilities, international student tuition, and enrollment. The government’s $32.4-billion education budget in 2022 did not impress Karen Brown, president of the Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario, who said the plan still “falls far short” of what students and education workers deserve.

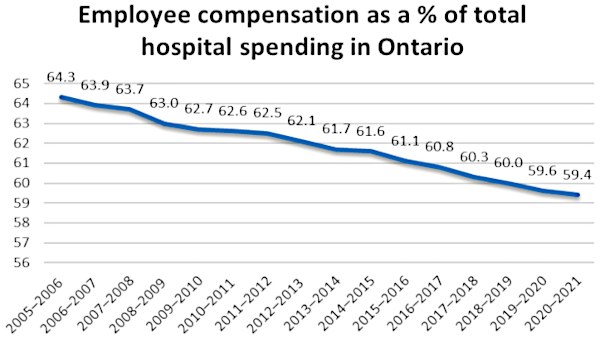

Public Sector Management

The Ford government targeted workers directly employed by the provincial state and in the broader public sector for wage suppression. Bill 124 gained Royal Assent in 2019 and imposed a 1 per cent wage increase per year for 3 years on most workers employed by organizations that receive funding from the province, including nurses and teachers bearing the brunt overwork from the pandemic. The bill was condemned as unconstitutional and unfair by unions representing public workers, and they called for it to be repealed. The material consequences of wage control are immediately obvious when examining the rate of inflation in Ontario: by April 2022, the price of consumer goods in the province had increased 6.8 per cent compared to the same time a year before. In other words, workers restricted to a 1 per cent wage increase will not only see that increase obliterated by a substantially higher cost of living, but fall behind a further 5.8 per cent.

However, some employees paid by the province escaped the wage regime. Despite claims by the OPC Party government that it planned to address the provincial budget deficit in 2019, Ontario Provincial Police officers were awarded yearly raises of 2.15 per cent – more than double the limit that would eventually be imposed on other public sector employees. Glaringly, Bill 124 was introduced just days after OPP officers achieved their pay hike. Only weeks after, the Association of Municipalities of Ontario identified the province as the Canadian subnational state with the highest policing costs in Canada. Such increases in resources for the coercive apparatuses of the state, while social spending is cut, have been a characteristic of neoliberal governance everywhere.

The State and The Private Sector

The neoliberal practices of privatization and marketization of the state continued to gain ground in the Ontario state during the Ford government’s tenure. For example, in 2020, as the province struggled to meet demand for personal protective equipment, the Conservatives announced plans to establish Supply Ontario, a supply chain agency extending commercial contracting-out of internal state supplies and services. Key to the creation of the agency were its mandate of accessing critical commodities in a “financially responsible way,” the promise that the agency would “stimulate job creation and economic growth,” and the claim it would connect “small businesses and entrepreneurs to government and its customers.” The board of Supply Ontario is composed entirely of executives, nearly all of whom are drawn from the private sector. In terms of marketization, the 2021 budget prioritized “lean and continuous improvement principles across [state] programs” in an effort to intensify efficiency.

It also promised intensive automation and digitization to facilitate 24/7 interactions between the state and capitalist class, and ever-more move the state toward “delivering customer‐focused services.” Infrastructure development in Ontario also continued to be ruled by public-private partnerships (P3s). For example, in 2020, the province announced “40 major infrastructure projects across the province using the P3 model.” Projects linked to that public-private bonanza, valued at more than $60-billion, included public transit, jails, healthcare facilities, and child treatment centres.

Transportation Infrastructure

Ontario’s transportation portfolio is among those emblematic of the neoliberal moment of capitalism in the province. At both the provincial and local levels, P3s have been embraced for public transit. Among the major projects to employ this model have been the proposed Ontario Line, an $11-billion 15-station rapid transit line announced in 2019 designed to connect Exhibition/Ontario Place to the Ontario Science Centre in Toronto, and the Presto fare system used across the Greater Toronto Area and Ottawa. The OPC Party claimed the Ontario Line, which will run both above and below ground, will carry 388,000 riders and remove 28,000 cars from the roads each day, as well as reduce crowding at transit stations, and create jobs. The Ontario Line, which is to be developed as a trio of P3s, emerged from the ashes of the so-called Relief Line, an eight-stop subway line designed to reduce congestion on Toronto’s subway system. The project encountered resistance from some residents along the route, who argued the Ontario Line’s design was finalized without an environmental assessment, and that trees and parks will be severely affected.

For context, Ontario’s track record with transit P3s has been less than stellar, according to its own financial watchdog. A 2020 report by Ontario’s Auditor General found Metrolinx, the Crown agency responsible for Presto, had grown increasingly reliant on the fare system’s original private sector service provider, Accenture. In 2006, the province, under the previous Liberal Party government, contracted Accenture to build what became Presto. After 2012, as Presto expanded, Metrolinx hired Accenture for more work, totalling $1.7-billion. That work was agreed to under the existing contract “without competitive procurement,” the Auditor General found. Perhaps unsurprisingly, public-private partnership industry lobby groups have been vocally supportive of the P3 model used for transit in Ontario.

The infiltration of private interests into public infrastructure was not limited to public transit. Questions were also raised about Highway 413, proposed to run across York, Peel and Halton regions, which some critics say would cut through sensitive provincial Greenbelt lands and add greenhouse gases linked to climate change. A newspaper investigation in 2021 found eight of the province’s highest profile land developers – half of whom are connected to the OPC Party through party operatives and lobbyists – own large tracts of land near the proposed highway route. Despite these concerns, the government reiterated its support for constructing Highway 413 in its 2022 budget.

The last four years of state policy show the Conservative government of Doug Ford has been unrelenting in its implementation of neoliberal policies. Even during the pandemic crisis, it is the practices of neoliberalism by which emergency spending measures have been implemented. In terms of fiscal policy, the government demonstrated the ideological faith that private market forces will restore revenue flows to the province, even as its own projections revealed economic growth and employment will slow over the long-term, and together with budgetary restraints balanced budgets will return.

The political setting for Ontario’s working classes is not good. Some proposals announced by opposition parties such as pharmacare by New Democratic Party, and greatly reduced transit costs by Liberal Party are positive first steps. But they are put forward at a time when the Ontario welfare state is in tatters and the least generous in the Canadian federation; and by parties positioning themselves as offering competing electoral visions. In any case, there is nothing that will break the neoliberal hold on the policy regime of the Ontario state. Workers can vote in the Ontario election but the votes do not provide an escape from the neoliberal consensus offered by the major parties. At the most, the election can rid the province of Ford and block some of the worst of the Conservative government’s proposals to build – the favourite word of the Conservatives – capitalism in ever more ecologically reckless manner with little regard for workers.

The current situation is not sustainable and the pile of evidence that reveals new polarizations in a fragmenting society is growing daily. The working class in Ontario needs to begin a long process of rebuilding, fighting back, and remaking a transformative politics capable of breaking the neoliberal policy agenda so deeply embedded in the Ontario state. A different future awaits if we can recapture the political ambition to construct it. •