Portugal Elections: ‘Socialist’ Party wins but Defeat for Left

The general election in Portugal (January 30) was triggered last October by the decision of the anti-capitalist Bloco Esquerda (Left Bloc) and the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP) to vote down the proposed budget of António Costa’s Socialist Party government. The left was opposed to the creeping privatization and lack of resources allocated to the SNS – the national health service – and the failure to increase sufficiently the national minimum wage.

| Portuguese Election results so far (2022 compared to 2019) (226 out of 230 seats declared) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Party | % 2022 | % 2019 |

| PS (Socialist Party) | 41.7 (117 seats) | 36.4 (108 seats) |

| PPD/PSD (Centre Right) | 29.3 | 27.8 |

| Chega (neo-fascist) | 7.2 | 1.3 |

| Initiativa Liberal | 4.98 | 1.3 |

| PCP (Communist) | 4.4 (6 seats) | 6.3 (12 seats) |

| Bloco Esquerda | 4.5 (5 seats) | 9.5 (19 seats) |

| CDS (right-wing) | 1.61 | 4.2 |

| PAN (animal rights) | 1.53 | 3.3 |

| Liberal | 1.28 | 1.1 |

The Costa government had not achieved an absolute majority in 2015 but these two parties had agreed to let it form a government after an agreement on certain policies that defended living standards and some other progressive measures. It was external support on a policy by policy basis, the left did not join the government and take ministerial positions. In this way they had a different approach to the Unidos Podemos left party in the Spanish state which is a full part of a PSOE (Spanish Socialist Workers Party, similar to Costa’s PSP) led coalition. Unidos Podemos has moved away from its original position of a radical break with the system.

Majority Government for Social Democrats

António Costa had always been constrained by the arrangement struck with the left parties so he was quite prepared to carry out the break with the left and try for an absolute majority. He needed 116 seats and at the time of writing has 117 so it is a political victory for him and his party. From the point of view of the working people of Portugal – who already are among the poorest in Europe – this is a real defeat. Here was an opportunity to strike a blow against the pro-capitalist moderation of the PS and to reinforce the weight of the left to put forward policies to defend their living standards and progressive policies. Unfortunately, this did not happen. Costa will have no need of an arrangement with the left going forward even if he will make a great play of his openness to dialogue. Obviously, the left will be discussing this defeat in more detail in the coming days and months but we can already suggest a few reasons for the setback.

In a time of COVID there is probably a greater concern among people for stability and security. Costa played this card very well, emphasising how the deal with the left was preventing this moderate government from managing the country out of the crisis and using its share of the EU recovery funds. It was easy for the government and a supportive mass media to present the left parties as being the disruptors, the splitters who were sabotaging a ‘national’ recovery. We have seen elsewhere national leaders getting an electoral ‘bounce’ from their leadership during the pandemic – even (UK Prime Minister) Boris Johnson benefited for a while.

Costa’s declaration after the vote said the Portuguese people had ‘showed a red card to the political crisis’ and a ‘desire for stability and security’. For his part, he promised a ‘dialogue with other parties’ and to promote ‘the necessary consensus in Parliament and between employers and working people’. He announced that in the next few days he will meet with all the parties, except Chega (the neo-fascists), and that he will form a ‘smaller, leaner’ government with the mission of ‘reconciling the Portuguese with the idea of an absolute majority’.

Incidentally, for those opponents of proportional representation, including on the left, this election shows you can get absolute majorities under a fairer electoral system. Also despite the left’s defeat the more democratic PR system in Portugal means they can hang on to a smaller group of MPs and therefore benefit even in defeat from a national presence on the media.

Strategic Voting?

During the campaign there was a growing polarization between the two majority blocs – the PS and the right of centre PSD (Social Democratic Party but actually on the right). Indeed the polls suggested that the PSD was neck and neck with the PS. This may have impelled former Bloco or PCP voters to vote usefully for the PS to ensure that the PSD would not get into government.

In the absence of big mass struggles and campaigns – not helped by COVID conditions – it must have been difficult for the left to win support for its rejection of the Budget. A principled position does not always lead to success electorally. The Bloco lost over half its votes and went down from 19 MPs to 5. The PCP won slightly less votes but kept six MPs (down from 12). From being the third national political party the Bloco is now the sixth. It shows how anti-capitalist parties can develop a strong core vote of around 5% but can also get into double figures if it successfully relates to mass concerns and struggles.

When working people are in retreat and right wing populist ideas are on the rise it is difficult to sustain the support of those less radical layers who will vote for you in certain periods. One of the difficult tasks of a radical left group is how to sustain the current through those difficult periods. It is easier if the political culture of the group does not become too electoralist and maintains a primary orientation to developing self-organization and in the workplaces and the communities. Resources available for the party and media presence will rise and fall with changes in electoral fortunes. So far the Bloco has managed these ups and downs relatively well compared to some other currents such as the Rifondazione Communista experience in Italy for example.

The Bloco does not see itself as primarily an electoral party but rather as a useful instrument for building a socialist alternative on the ground. To give one example, one of its comrades, Alberto Manos is a leader of Solidariedade Imigrante which works with migrant communities. The Guardian recently ran a story about how British supermarkets were selling soft fruits picked by exploited migrant workers in Portugal and it referenced Alberto and his work.

Rise of the Right and Far-Right

The rise of the far right Chega (literally, Enough!) was previously forecast by the 11% vote its leader, Andre Ventura, got in the 2021 presidential elections. Although he got around 7% and 12 MPs for his party this time, it consolidates a presence in parliament and guarantees regular airtime for its anti-migrant, nationalist poison. Until 2019 when he set up Chega there had been a minimal presence of neo-fascist or far right parties in Portugal where a fascist style regime had been swept away by the revolutionary upsurge of 1974. During the campaign Ventura made a particular target of the ‘communist’ Bloco. Anti-racist and anti-fascist campaigning will be at the forefront of the Bloco’s work in the coming period.

Alongside the rise of Chega, we also saw an increase in support for the ‘modernizing’ neoliberal, pro-business party, Liberal Initiative which just pips the Bloco support at nearly 5%. The success of both these groups reflects the crisis of the right of centre parties. For the first time the historic CDS (People’s Party) which was in government in 2015 has failed to win any seats in parliament. The absolute stalling of the PSD vote has resulted in its leader announcing he will go. Today the dominant sectors of the ruling class are quite happy to have a moderate Socialist Party protect their interests and maintain stability.

To complete the whole picture the animal rights and ecological party, the PAN now has only one MP and halved its vote to 1.6%. Polarization toward the PS has affected all parties.

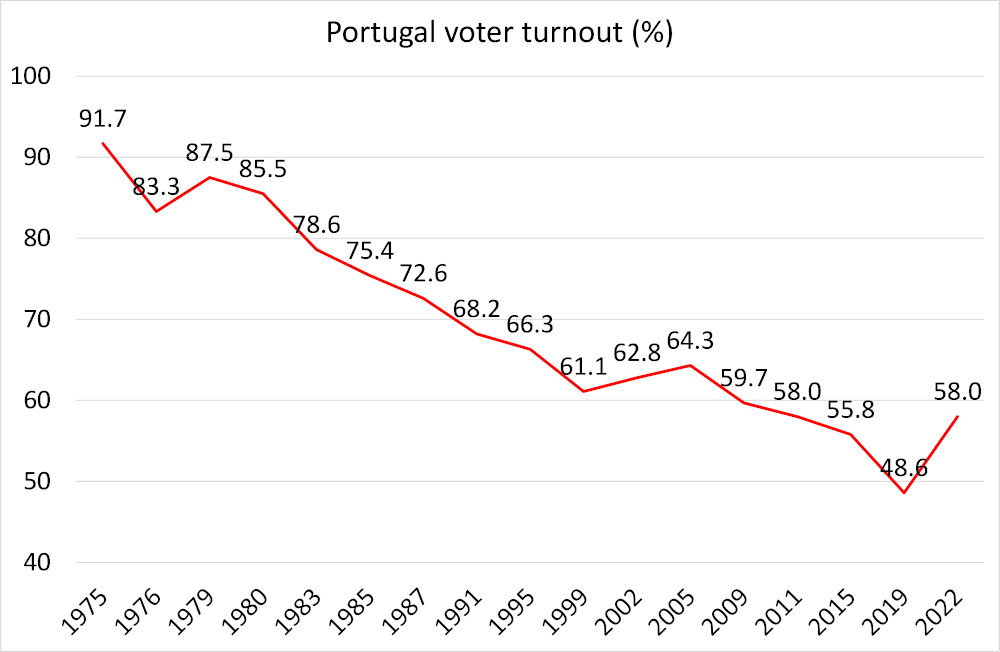

Last but not least, the abstention rate was less than in 2019 but there are still 42% who did not bother to vote. Costa is not leading some sort of mass upsurge for his version of social liberalism. This figure expresses a trend seen elsewhere in Europe and reflects a growing alienation from the political process. For the left it sets out an audience that we need to address and win to a radical alternative. At the same time it is a reservoir of potential support for the right wing populists and the neo-fascists.

Statement from Bloco Esquerda issued on election night

“We will know how to carry out our commitments to this country and to those we work with.”

On election night, Catarina Martins stated that the party will face up to “the current difficulties” and will continue the struggle. The electoral result is also bad because of the growth of the extreme right and “each racist MP elected in the Portuguese parliament is one more racist deputy” that the Bloco promises to fight. The results “do not make us forget our mandate” and that the Bloco will know how to “live with” the consequences of the vote.

The Bloco’s coordinator considered that “the PS’s (Socialist Party, current government) strategy of creating an artificial crisis was successful.” At the time of this statement, the PS was “close, or had already won an absolute majority.” The bipolarization developed during the electoral campaign “was false” and that’s why the campaign was “very difficult,” since it created “enormous pressure to vote ‘usefully’ that penalized the parties to the left” (of the PS).

Besides the likely absolute majority being bad news for the country, the result is also poor, according to Catarina Martins, “because of the extreme right” vote of the Chega party. Although its result falls “short” of the one André Ventura obtained in the presidential elections, “every racist deputy elected in the Portuguese parliament is one too many.” “We will be here to fight it,” she promised.

Given tonight’s results, causes like the defence of the National Health Service (SNS) or the fight for a decent salary and against precarious jobs “don’t get any easier.” But we also know that we will not be absent from these struggles” and “we will be side by side with the people in the struggles.”

Questioned once again about how the party voted on the Budget, Catarina Martins added: “we didn’t reject the Budget because of any electoral tactic.” “We knew that we ran an electoral risk.” We voted that way with the “deep conviction” that the Budget worsens the situation of the National Health Service and of those who live from their work and have had “salaries frozen for so long. Pensioners have also been losing out as their pensions are worth less and less.” What happened this Sunday “doesn’t mean that we start believing that the Socialist Party Budget was good. It wasn’t.”

For the Bloco, “the reasons for opposing it are not invalidated by our result” and, in fact, “parties should not change their convictions for electoral reasons like the way they change their shirt.” Thus, “it is necessary to continue to fight for our demands.” There are a million people without a family doctor. Hospital emergency rooms that are daily not able to respond to the needs of the country. So many people live in increasingly worse conditions because their salary is stuck at the minimum wage and has not progressed for more than a decade.” •

This article first published on the Anti*Capitalist Resistance website.

Portugal: Socialists on Their Own

Portugal’s ruling socialists under prime minister, António Costa, achieved a surprising victory in parliamentary elections on Sunday, January 30. The Socialists gained an outright majority in the new parliament over all other parties and will be able to rule without a coalition. The previous so-called gerigonca (contraption) coalition broke down last October when the leftist parties (Communists and Left Bloc) left the coalition over what they saw as an austerity budget being proposed by the Socialists.

Costa called a snap election expecting to have to form a new coalition. However, the Socialists took 41.7% of those Portuguese who voted, up 5.4% pts from the 2019 election, while the Leftist parties lost 6.9% pts. So the total left vote share actually dropped from 52.3% to 50.6%. The main right-wing party, PSD, did better too, rising from a 27.8% share to 29.3%. But the small ‘centre-right’ parties lost ground, so the Socialist victory was secured.

In effect, there was a consolidation toward the main traditional left and right parties. Except for one thing: there was a sharp rise in the far-right Chega (Enough!) party, which took 7.2% of the vote to become the third largest party in parliament. That’s a sign of things to come if the Socialists cannot deliver on improving living conditions and prospects for the Portuguese people, the poorest in Western Europe.

Voter turnout has been steadily falling since the first democratic election in 1975 after the revolution to overthrow the military dictatorship under Salazar. Then the turnout was 91.7%. In the 2019 election it had fallen to just 48.6%. Sunday’s turnout jumped to 58.0%, the best since 2009. Even so, the ‘no vote’ share of 42% easily outstripped those who voted Socialist (one in five) by some way. Disillusionment in parliamentary democracy remains.

Governing During a Pandemic

The previous coalition government had supposedly done better than most in response to the pandemic, with one of the highest vaccination rates; but the death rate was still high and only kept within bounds because the Portuguese people showed great solidarity in following restrictions to protect health.

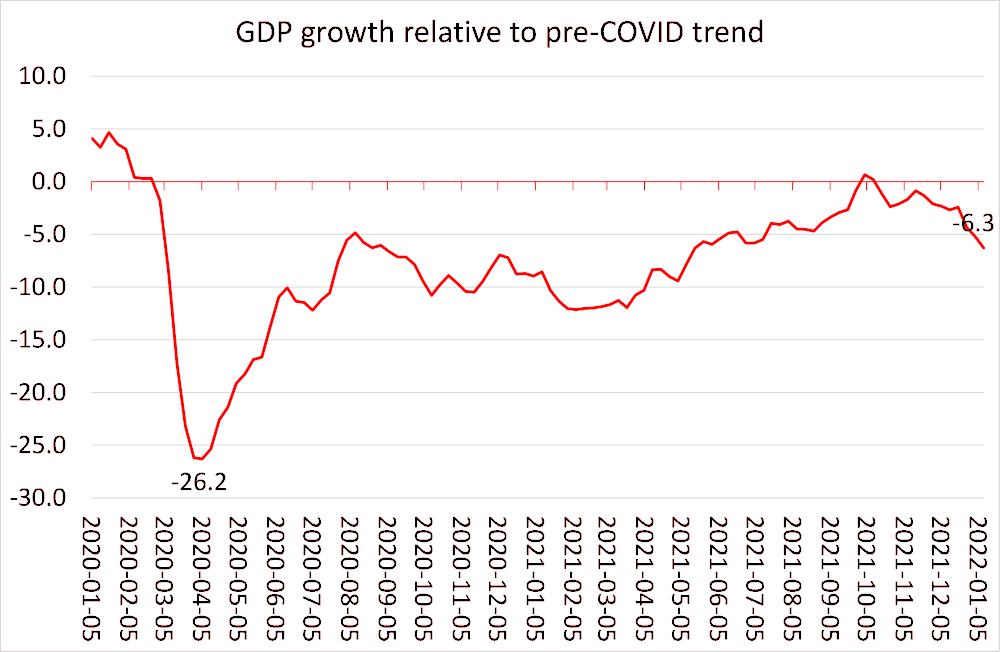

The pandemic was a disaster for an already weak Portuguese economy. Portugal has been called ‘sardine capitalism’ after its famous connection to the production of that fish. But this is misleading: agriculture and fisheries contributes less than 2% of annual GDP and only thousands in employment. Much more important in an economy where manufacturing output and investment is relatively low is tourism. Like Greece, tourism contributes a massive 20% to annual GDP and that has been decimated by the pandemic slump. Portugal’s economy is still well below the trend level before pre-pandemic.

The Costa government came to power pledged to reverse the post 2008 slump austerity policies imposed by the Eurozone. Like other governments in southern Europe in the last decade, it made little progress on growth, productivity and investment, even if it avoided even worse austerity measures. Productivity has been flat for the last eight years.

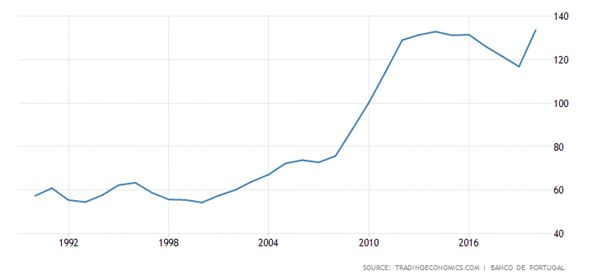

Productivity level (index = 100)

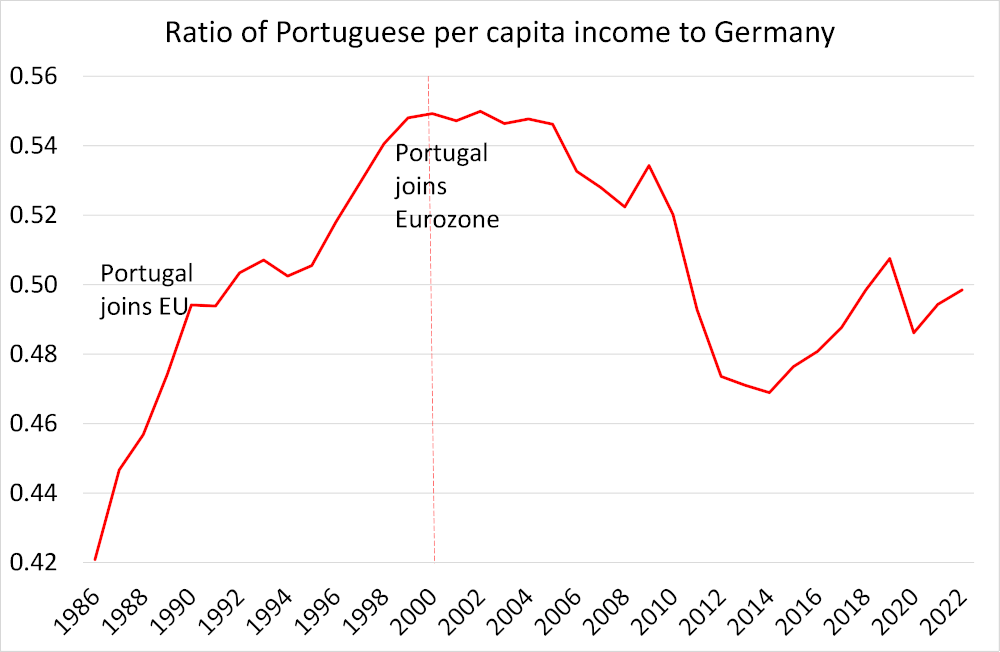

Portugal’s economy has been falling behind the rest of the EU since 2000, when its real annual GDP per capita was €16,230 ($18,300 US) compared with an EU average of €22,460 ($25,330 US). By 2020, Portugal had edged higher to 17,070 euros ($19,250 US) while the bloc’s average surged to €26,380 ($29,750 US).

The European Union supposedly aimed to ‘level up’ the weaker capitalist economies with the richer core. The opening of trade and investment after Portugal became a member in 1986 appeared to work, as it did for other weaker EU countries. But the introduction of the euro changed all that. Whereas before the weaker EU countries could let their currencies depreciate against the deutschemark to try and remain competitive. That was no longer an option in the Eurozone. Without higher investment and productivity, the weaker capitalist members could not compete. Convergence turned into divergence. Portugal like other weaker members was reliant on FDI from Germany and France. External debt rose sharply and the Euro debt crisis in 2012 in the wake of the global financial crash pushed the country into penury and austerity.

Meanwhile low wages and high unemployment spurred emigration – a feature really since the 1960s. Over the past ten years – a period that includes governments run by both the Socialists and the ‘centre-right’ Social Democrats – some 20,000 Portuguese nurses have gone to work abroad, in an unprecedented drain of medical talent. The youth unemployment rate is still 25%.

Youth unemployment rate (%)

Average pay is just €1,300 ($1,466 US) a month. Among all OECD countries, Portugal has the sixth-lowest average salary but the highest rise in housing prices. Portugal saw the lowest public investment across the European Union in 2020 and 2021. That was part of the reason the leftist parties pulled out of the coalition.

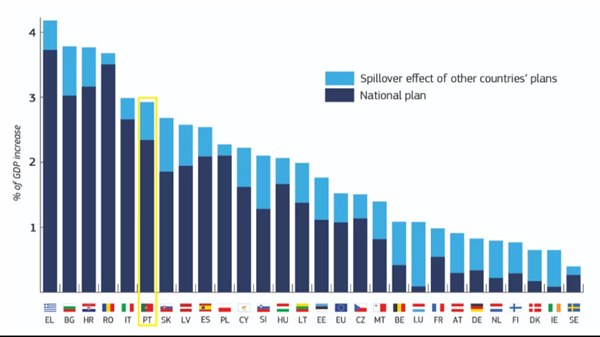

The Socialist government now takes full responsibility for improving conditions for the 99% in Portugal. It is putting all its hopes in the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Plan, which pools funds from the richer members to help out the weaker economies – the first time such a fiscal package has been employed across the EU. The government reckons that the European pandemic recovery plan will have an economic impact of €22-billion ($25-billion) through 2025, and as a result Portugal’s GDP in 2025 will be 3% higher than it would be without that plan.

EU Plan impact

That’s the hope. But the money still comes with strings: namely that the government is supposed to maintain a tight fiscal policy and keep budget deficits down and above all start to reduce its huge public debt ratio.

Public debt to GDP (%)

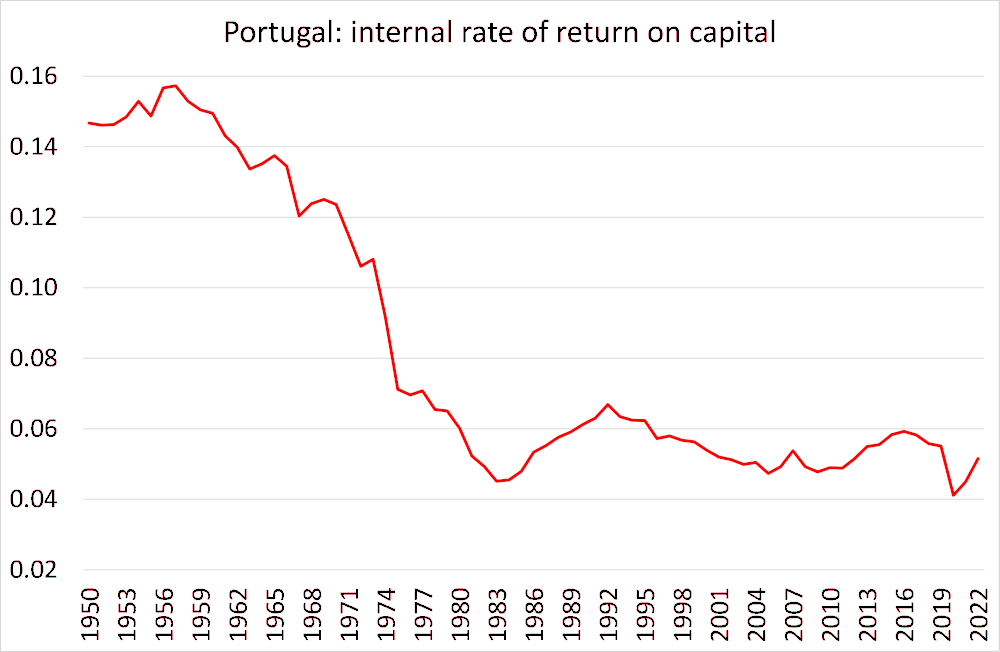

Even though the Socialist government will be getting funds from the EU to spend on infrastructure and services, it is likely to do little to get a very weak capitalist sector to invest and expand employment and raise wages. That’s because the profitability of capital in Portugal is miserable. It has been flat and low for 40 years. The EU has done nothing for Portuguese capital up to now.

Portugal is a tiny country with just 10m population and a $200-billion economy. Under capitalism, it is subject to the ‘kindness’ or otherwise of ‘strangers’ (ie German and French capital). And the new Socialist government has no intention of changing that. •

This article first published on Michael Robert’s blog.