Canada’s Eviscerated Democracy: Minority Government and Representative Democracy as Symptoms

On 20 September, 2021, Canadians voted to hold the line. While forty seats changed hands, the number of seats won by each of the parties was so close to the ones they already held that the overall outcome was startlingly similar. Once again, the Liberal Party will form a minority government that will have to depend on the support of other parties to get its programmes and policies implemented. No substantial change. The leader of the Bloc Quebecois was heard to mutter that the election surely had not warranted the interruption of people’s barbeques.

For those who see Justin Trudeau as an opportunist, a rather hollow man whose interest in politics is dominated by his urge to satisfy his ego, the result might give rise to some malicious pleasure. They remind everyone that Trudeau had brazenly betrayed his promise not to call an election during the pandemic. His minority government had been able to push through its policies and programmes without much trouble at all, but he could not resist his lust to be the leader of a majority government. For these Trudeau critics, the resultant minority government is to be welcomed because it showed that voters resented Trudeau’s self-promotion.

But many others, not as spiteful as the anti-Trudeau crowd, also applaud the election of yet another minority government. They believe that a minority government is not only a common but also a desirable result.

Anxieties About Minority Governments

It is true that a minority federal government is a common outcome. The only thing that made the 2021 outcome remarkable was its virtual duplication of the result obtained in 2019. That aside, the end result, a minority government, is par for the course. Five of the last seven federal governments have been minority governments. Parties have governed with the support of other parties in the House of Commons without feeling the need to form a coalition with any of them, without feeling the need to make them part of the government. Largely, this is a consequence of our first-past-the-post electoral processes. When more than two political parties are involved in a first-past-the-post election, it is exceedingly difficult for any one of them to win 50.1% of the votes cast. Still, logical as it may be to expect a minority government to reign, it does not mean it should be greeted with approval.

The fact is that the repeated failure to craft majority governments does create some anxieties. Since 1921, any election that brought a minority government into office has spurred a discussion about the need to change the voting system. There seems to be a residual sense that to have a minority government entrusted with so much power for a considerable time is not what those who fought for the franchise had envisaged. The history is well-known.

The universal franchise, which now fills us with pride and seems normal and natural, only came into being after many struggles. Initially, the only people allowed to vote were owners of property and wealth. They not only ruled the elected government but also the economic sphere. Given their lack of economic power, the marginalized, the voice-less, pushed to have their numbers count. After all, in numerical terms, they constituted (and constitute) a whopping majority. They wanted to control a government to off-set the economic power of the few, of the wealthy. The universal franchise was the means to ensure that numbers, rather than dollars, would count. Incremental step by incremental step, we did get a universal franchise. Perhaps because it had met with so much opposition from the wealthy ruling class, we have come to equate democracy with the universal right to vote to install a party as a government if it has gained a majority of the votes cast. The majority’s wishes are then to be the legitimate goals of society for as long as the government stays in office. Numbers are to count.

This starting point is what creates such angst within the ranks of cheerleaders for electoral democracy whenever a minority government gains office. Despite the loudly trumpeted claim by a newly elected minority government that it has won a mandate, this is a highly problematic, if not bombastic, claim: a minority government does not reflect the majority’s views and hopes; it does not fulfill the aspiration of those who fought for the extension of the vote. This sense that something has gone awry is widely shared and very strong. It is why Trudeau had promised to change the first-past-the-post voting system when he entered the 2019 election. As it turned out, in that 2019 election, the Liberals were unable to win a majority but were able to form a government even though they collected fewer votes than the Conservative Party had. The first-past-the-post scheme had delivered Trudeau this boon. Unsurprisingly, the promise to reform the voting system (along with quite a few other promises, it must be said) disappeared from the Liberal Party’s agenda. It is very easy for a political party to love a system that gives that political party a win when it has actually lost.

Nice work if you can get it and, in Canada, you can get it all the time.

Justifying Minority Government

In the end, the failure to deliver on Trudeau’s 2019 electoral-reform promise did not loom large in the 2021 election. One of the reasons may be that, while there are always some who worry about the downside of what, in principle, it means to produce so many minority governments, many more feel that, in practice, a minority government delivers the best results. In essence, that kind of belief rests on a claim that a government with a majority may act autocratically. There being no need for it to have to placate opposition parties for four years, a majority government might be tempted to impose its favourite policies and laws, including policies and laws that the voters were not alerted about during the election. Indeed, if it does spring such unpleasant surprises early enough during its reign and then offers some bribes and sweeteners when it has to go to the electorate again, it may well avoid punishment.

The extremely right-wing Harris-led Conservatives won a majority in 1995 and instantly introduced a system of workfare and reduced welfare benefits by a jaw-dropping 21.6%, an onslaught from which the social welfare system has never recovered. A few years later, the Harris government was re-elected.

The reasoning that undergirds the argument that we should be wary of majority governments was the same as that used by the owners of wealth when they were the only ones with voting rights. They strenuously opposed enlarging the franchise to include the masses of the wealth-less. These poorer people might use their numbers to victimize the owners of the means of production, a minority if ever there was (and is) one. Those who use this kind of reasoning today strive to sound more benign. They say that they are fearful that a majority government might use its powers not to attack the rich and powerful (still a distinct minority) but rather, the vulnerable; they might discriminate on the basis of unacceptable criteria, such as race, religion, ethnicity, sexual orientation, etc. This solicitude for the potentially oppressed is reflected in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. It guarantees a number of listed rights for individuals that may not be overridden by properly elected governments unless such a government can persuade a court that setting aside a Charter-protected right is justifiable to achieve a result that dovetails with a democratic polity’s needs.

Occasionally, a legislature will insist on its Charter-breaching law or policy despite an adverse decision by a court. It may invoke the notwithstanding clause, a provision included in the very same Charter. Its inclusion in the Charter is an acknowledgment that in a self-declared liberal democratic polity that presents its electoral institutions as the very core of democracy, the will of the people as expressed in an election must be respected. Yet, when a majoritarian government does, or threatens to, override a judicial finding that its law or policy offended a Charter right (e.g., Ford when reducing the number of municipal representatives, Ford when amending third-party political funding, Quebec when making French the privileged language, Quebec when prohibiting the wearing of the hijab or other religious symbols), the properly elected and legitimate government is lambasted for its lack of respect for democracy.

In sum: there are sincerely held reasons and beliefs that lead conventional commentators to accept minority governments whenever they emerge from the electoral processes. This leads to the validation and legitimation of some amazing outcomes. If one looks at the votes actually cast by voters, this latest election, much as had been the case in 2019, produced counter-intuitive results. The Conservative Party, with 33.7% of the votes, finished slightly ahead of the Liberals who garnered 32.6% of the votes cast. Yet, the Liberals elected more members of Parliament. This happened because many of the seats won by the Conservatives were won by whopping majorities, up to 70% of the votes cast in some electorates. In the first-past-the-post system, 29.9% of those Conservative votes had no direct impact on the result. The Liberals won in more electorates with much smaller margins, leaving them not only with fewer votes overall but also with fewer ‘wasted’ votes. In an even more dramatic illustration of the vagaries of the voting system, the Bloc’s national share was only 7.6%, but they won enough seats to become the third party in Parliament, ahead of the NDP.

Now, in truth, the votes that are not necessary for a party to win any particular election should not labelled ‘wasted’ votes. These (unidentifiable) voters will have the satisfaction of knowing that a person whose views they favour will represent them in Parliament and, if they are lucky, in government. But, in the end, it is also true that the number of votes does not count as much as they might: the greatest number may not win. This is so because what matters is the number of seats won, rather than the number of votes won.

One of the aspirations of the early progressive universal franchise promoters, namely to ensure that the wishes of the majority of individuals in society should hold sway, has been side-lined. It is the convention that the party with greatest number of seats – the Liberals in both 2019 and 2021 – should be given a chance to govern even if it has not won the support of the majority of the votes cast.

It is given the opportunity to do deals with its competitors, which is a curious notion. During an election campaign, each of the mainstream parities expend much of their energy on showing how different they are from all the others when it comes to the kinds of policies they favour and the world views they hold. They type-cast themselves and their opponents; they call each other nasty names; they unearth scandals, contradictions, any evidence about the fecklessness of their opponents, all to show they cannot/should not be entrusted with government. Yet, after one of these parties is given a chance to govern, it is expected to form an alliance or a set of ad hoc alliances with its (supposed) deadly enemies.

Why do so many opinion moulders think this leads to good government? Confronting that question reveals quite a deal about our democratic institutions and practices.

Different But the Same

It is understood that, occasionally, a minority might not be able to fashion an accommodating deal. But rarely. If an impasse is reached, it is more than likely that one of the deal-making parties will see an opportunity; that is, it believes that an election will suit it, much as Trudeau reckoned when he forced an election this year. It was not that he could not get his government’s agenda implemented by deal-making but that he thought he could smash his rivals. That aside, those who favour minority governments do so because they have the capacity to avert abuses of power, which can work because what unites the mainstream parties is more important than what divides them. This understanding is rarely explicitly articulated, as the elites like to characterize elections as competitive horse races during which widely diverging views are debated and reconciled. This is meant to, and does, give the impression that our democratic practices are richer than they are. It hides reality, a reality to which I turn.

All of the mainstream parties accept the framework of contemporary capitalist relations of production. If this were a theoretical piece, this assertion would require an extensive elaboration, but here, I will restrict myself to some of the more obvious features of this internalization of capitalist relations of production. First, while the parties differ on how to strike a balance between the unfettered capitalists’ drive to maximize profits and the need to restrain them from time to time because the outcomes are just too painful to bear (and might delegitimate the government that allows such excesses and, in the end, capitalism itself), all the parties accept the sacrosanct nature of private property. Owners of property are deemed to have the right to deploy it as they like and to exclude others from its use. Second, they all agree that the best way for a government to provide overall welfare is to allow the owners of the means of production to pursue their drive to accumulate more wealth, to achieve higher profits. The private sphere is seen as the primary engine when it comes to the creation of wealth. The hope is that as profits are pursued, somehow all will benefit.

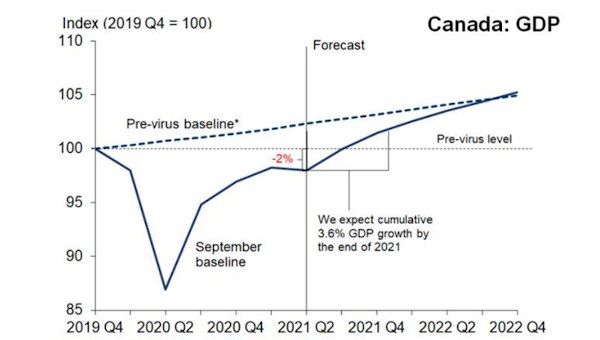

Third, all the parties agree that to make this kind of political economy work, it is necessary to pursue economic growth, as measured in monetary terms, and that this growth is to be led by the private sector. Each of the parties points to its unique plan to improve the GDP while pursuing this goal, thereby suggesting that they have fundamentally distinct platforms. But, fourth, it remains true that private property owners are encouraged to determine how they can best pursue their maximization of profits by each of the parties. Much of what the owners of the means of production do may add to growth in monetary terms without meeting any of the essential needs of society. The parties do differ on how best to fill some of the resulting gaps, but they all agree that they should be filling in gaps, while not negating the role the private owners of the means of production are to play in the generation of overall wealth.

These starting points go a long way toward explaining why none of the mainstream parties are able to confront the problems of the environment or of indigenous peoples’ effectively. They have denied themselves the necessary tools. None of them will attack the right to own and preserve private property; none will set their face against continued growth in monetary terms. It is this dynamic that explains the tremulousness when governments set standards – hobbled by their righteous reliance on the private sector, they will always ask the dominant sectors of owners how much regulation they will accept. The ensuing standards are low and, inevitably, poorly monitored and enforced.

None of this is to say there are not some serious differences between the parties, for instance, in their approaches to issues raised by race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, gun control, and the like. Let me acknowledge that these are far from negligible differences, but whatever any party proposes to deal with these kinds of issues, they do not feel themselves compelled to mount a direct challenge to the structures and ideology that maintain and perpetuate capitalist relations of production.

The argument here is that it is possible for those who welcome minority governments to contend that compromises can be engineered precisely because those compromises will be made within a capitalism-conserving framework. The deep structural needs and accompanying ideological messages are continuously re-enforced.

In 1994, James Bovard wrote, “Democracy must be something more than two wolves and a sheep voting on what to have for dinner.”

The Self-Excluded

The contention thus far is that parties come together easily because they do not differ all that much on what the core elements of social relations ought to be. It may be that this goes some way toward explaining why so few people care about which party will govern them. It turns out that many people who are eligible to vote choose not to do so. The numbers are arresting: they underline how governments are given power with only slivers of the total votes available. It turns out that minority governments are even more feebly connected to the wishes of the public than is commonly thought.

As is now usually the case, the number of people who did not vote formed the single largest bloc in the 2021 election. Much has been made of the fact that the Conservatives won 33.7% of all the votes cast, slightly more than the Liberals’ 32.6%. The NDP obtained 17.8%, the PPC 5.00%, the Bloc Quebecois 7.6%, and the Greens 2.3%. So, should the minority Liberal government get support on any one issue from, say, the NDP or the Bloc, the numbers of voters seen to support that specific issue will represent something akin to a majority of the actual votes cast in the election. This tends to boost the cheerleaders for minority government: no compromises that would outrage the majority will result. But this kind of calculation is not all that persuasive.

Forty percent of the eligible voters did not vote, which means the numbers that suggest the major parties had garnered the support of one-third of the voters are fraught. As a percentage of the eligible voters (contrast votes cast), the Conservatives won 20.4%, the Liberals 19.8%, the NDP 10.2, the Bloc 3.7, the PPC 3.0, and the Greens 1.5 percent. The non-voting bloc was as large as the Conservative and Liberal bloc combined. The claim that a minority government has a mandate of any sort becomes that much more dubious; the notion that if two parties come together on an issue, a majority of the public’s views will be reflected becomes that much less credible. If not voting by eligible voters is seen as an expression of intent, the largest number of voters available have spoken rather strongly.

This point will not have much resonance if the assumption is made that the non-voters would have voted much the same way as those who did cast their ballots. But why should such an assumption be made? Or, some might think that those who did not vote were not only apathetic, but largely ignorant. Such an argument smacks of arrogance: why are twice the number of people who did not vote for either the Conservatives or Liberal more uninformed, less aware of the nature of their citizenship? After all, it might be just as plausible to believe that a great number of these non-voters did not believe that it mattered who won because they did not think it would make sufficient difference to their lives or, more worryingly, believed that choosing anyone on offer would be positively deleterious to their lives. Those who do not vote may just think that electoral democracy does not work for them. There are good reasons why that might be the case because there are many anti-democratic sites of power that impact on their lives in major ways.

I have come to the real thrust of this paper: vital decisions affecting all people are made by people and public and private institutions securely protected from democratic oversight.

Democracy Free Zones

First among the decision-making institutions where democracy is lacking is the elected government. The government has an inner circle, its Cabinet, which acts as an executive body. This executive counts on party discipline to implement its decisions. Its adherents in the legislature are expected to abide by its decisions. In effect, the executive wields the power held by the government. It imposes duties of confidentiality on its members. Secrecy and opaqueness shroud its deliberations. The citizens only have the most attenuated input into any central decision-making that will generate legislation, regulation, and overall policy. They can petition and lobby, but that is it. Their most important participation is to be allowed to cast a vote for one candidate in one electorate. At the time of voting, voters are forced to hope that, in a general way, one candidate and/or their party will best reflect the voter’s views on a huge number of issues and that the government will, therefore, approximate the government they would like to have.

Furthermore, voters may hold their noses because of that candidate’s/party’s views on some issues and still vote for them on the basis of a specific promise made on one or two issues or because, on issues significant to those voters, they are better than other candidates/parties, even though on many matters they may stand for things the voters do not want. In any one electoral district or riding, the reasons individuals have for voting for the same candidate/party will vary vastly. This gives the executive a lot of room to manoeuvre and manipulate, as it enjoys plenary, voter-unimpeded powers for extended periods.

The second institution in which vital decisions are made and in which democracy is, at best, an afterthought, is the judiciary. Courts are to ensure that elected governments do not exceed their constitutional powers. As well, as noted already, they are charged with striking down laws and regulations passed by governments if they interfere unnecessarily with the rights of specified minorities or individuals. The freedom to think, speak, assemble, associate, to be secure from police intimidation, to be free from discrimination, and the like are to be safeguarded by the judiciary. In short, they are to protect us from abusive elected governments. Having said that, questions arise.

Who voted for these judges? Who appointed them? Are the appointees likely to come from the ranks of those who question the status quo? Why is an unelected institution that, historically, never supported any liberal political values, except those embedded in private property and private contract to the detriment of the working class, to be entrusted with the freedoms won by working-class struggles?

The third point to make is that even elected governments do not have any direct power over many of the decisions that affect the public. This raises the question: what is all that election stuff really about? Consider:

• The police and security forces of our lands are beyond any meaningful public scrutiny. We are asked to trust machinery controlled by people who are closer to the police and its objectives than to us. The police and secret services frequently ask for, and get, powers to survey, detain, and bring charges in secret. Courts may be required to hold oversight hearings in private. We are to accept these distortions of the rule of liberal law because we will be allowed to protest about them at the next election, be allowed to vote without any likelihood that we will have had access to the information needed to do so.

• This is even more true when it comes to the military, where our lack of information and ability to participate is truly shocking. Wryly, Colin Leys, the British political economist, has noted that the defenders of neoliberalism, i.e., the clergy of the private market, their one and only true religion, never castigate the military, the police, or the judiciary as being too inefficient, as costing too much or as dangerous to people’s freedoms (as, to them, the State is). The anti-democratic nature of these institutions makes them appealing to capitalism’s cheerleaders. Their potential to control the pesky citizenry is much appreciated. Perhaps not so coincidentally, the internal organization of the police, the secret service, the military, and the judiciary is hierarchical, profoundly anti-democratic.

• The mature capitalist political economies have put their Reserve Banks, such as the Bank of Canada, that is, their money/currency controlling institutions, beyond the reach of democratically elected politicians, ensuring that only those with direct access to the reserve bank personnel have an effective voice. Needless to say, these people are culled from the ranks of the banks and other financial institutions, from the 1%, or more accurately, the 0.01%. Decisions that affect interest rates, purchasing and selling of housing, building and renovating houses, the capacity to import/export, and so on, are beyond the purview of direct democracy. Edgar Snowden refers to the US Federal Reserve as the United States’ 51st and most powerful State.

• What is true of the central banks is true in spades of the acronyms who rule the world; the World Bank, the IMF, the WTO, the BIS, the ECB, etc. Their private, secret decision-making, with only the rich and powerful at the decision-making table, does not even deign to nod at the principles of democracy. Their decisions impact on billions of people’s welfare without a hint of democracy. Even when elected politicians purport to be meeting as democratic representatives to deliberate on economic policies, as they do at the G8 and the G20 meetings, they are surrounded by veritable armies of representatives of the 0.01%. It is those people’s views that count, and only those people’s views, not those of the public at large. This explains the palpable anger in the streets of any city these leaders occupy when they meet behind police and army barriers.

• And, to top it all, everyone in the world is affected by the undemocratic decision-making inside huge corporations whose revenues and assets dwarf the Gross Domestic Products of most nation states. The decisions whether to invest, where to invest, how much to invest, what goods and services are to be produced have enormous impacts on what governments do, want to do, and can do. They limit a government’s real world (as opposed to its constitutional) jurisdiction. The decisions corporations make have immediate impacts on those people who need work, food, shelter, and goods and services. The corporate sector makes all those decisions without a smidgen of democracy adulterating its profit-seeking mind. Inside the corporation, there is a form of democracy – it is shareholder democracy, the obverse of real democracy. One dollar/one vote is the preferred decision-making model; the wealthiest should rule, is the motto. The workers who do all the work and take the risk of being injured, diseased, or killed and suffer the economic and environmental losses that corporate decisions may wreak, get no vote. Money counts; people do not.

Erich Fromm wrote that “[o]pinions formed by the powerless onlooker do not express his or her conviction, but are a game, analogous to expressing a preference for one brand of cigarette over another. For these reasons the opinions expressed in polls and in elections constitute the worst, rather than the best level of human judgment…Without information, deliberation, and the power to make one’s decision effective, democratically expressed opinion is hardly more than the applause at a sports event.”

Summation

1. In recent times, there has been much discussion among thinking capitalists about the efficacy of electoral democracy. For instance, the Toronto Star and TVO offered lengthy articles and programmes on how to make our democracy richer, more appealing to the population. The contention here is that even if electoral democratic practices are improved markedly, if we get rid of primitive first-past- the-post voting and/or have more proportional and/or preferential representation, and add compulsory voting, people will be only infinitesimally closer to the ultimate aim: to be in charge of their lives, to be in a position to determine how they are to realize their potential as human beings. The results in non-first-past-the-post jurisdictions like New Zealand and Australia provide sad and ample evidence. Centres of decision-making pivotal to people’s welfare will remain untouched. Those non-electoral loci of decision-making are staffed by those connected to the rich or by the rich themselves. A better voting scheme will still leave the 99% out of the most significant decision-making loops.

2. On the left, vigorous discussions take place on how to bring about the downfall of capitalism. One strain of the discussion is that there must be a way to control the State so that it can set out to occupy the commanding heights of industry and finance and begin the redistribution of wealth. The argument here has been that, to make headway, it will not be sufficient to win electorally. The processes are too tenuously connected, too limited in their ambitions and powers to curb the many centres of power focussed on serving capitalism at the expense of everyone’s and the planet’s interests. They must be the focus of democratization.

3. Anti-capitalists must exploit this moment of anxiety about democracy to push for democracy in every sphere. It is easier said than done. However, if this objective is kept at the forefront of our minds, it will not be as easy as it has been for capital to confine us to the parliamentary arena where the potential for radical change is non-existent. And we do need radical change. Many people are ready for more democracy, for real democracy, not just for better electoral democratic practices. All political action, no matter how specific or local, should be coupled with demands for more direct decision-making power by the very people to be affected by a decision or practice. Economic democracy, democratization of public and private institutions, should be the focus of invigorated struggles. Only then will gains made in the electoral sphere bring meaningful results to those who want a better world.

In Radical Democracy, C. Douglas Lummis wrote: “Democracy is a word that joins Demos – the people – with Krakia – power… It describes an ideal, not a method of achieving it… It is a historical project… as people take it up as such and struggle for it.” •