Capitalism’s Wet Dream: Amazon’s Patents Signal the Future It Hopes to Achieve

In anticipation of increasing robotization, two poles tend to emerge within discussions about the future of work: at one end, a post-work utopia of fully automated abundance; at the other, a dystopia of unemployment and immiseration.

Necessarily, both projections are speculative. Seeing as we cannot know the future, predictions about technology and work are developed by considering existing tendencies in tandem with our own ideological interpretations. There are very good political reasons for such speculations: we use them to imagine a better future and to try to attain it. Yet speculation can be coupled with the analysis of more concrete clues.

Patents are one way we glimpse potential futures at work. As documents that grant property rights over industrial innovations that may not yet exist, what we see in patents is the forces of capital sketching out their desires for future technology – whether new commodities to sell or new tools to organize work and production. Through patents, corporations literally own the future: patents include the design and rationale for new technologies, and can be used to fence off competitors and steer innovation in particular directions. They are also public documents, fully accessible and searchable, which describe prospective technologies in detail and can be exploited strategically to study capital’s plans – and perhaps counter them.

Amazonian Vision of Work

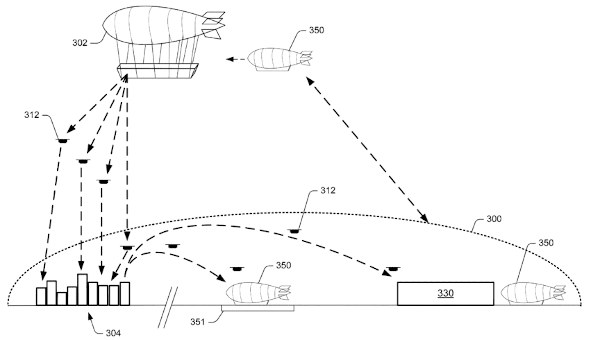

Take Amazon for example. The multinational corporation invests heavily in technological research and development, filing hundreds of patents per year. The company is also a source of anxiety as a prime driver of the sort of automation that could lead to unemployment: many imagine a future where Amazon’s warehouses are fully automated, with robots packaging orders and drones delivering them, while hundreds of thousands of workers are left unemployed.

But while today’s massive fulfilment centres rely on masses of workers performing physical and repetitive tasks, alarmism about technological unemployment being driven by Amazon is not entirely unfounded. In a number of fulfilment centres, the company deploys robots that move shelves around the warehouse floor, bringing them to workers at fixed workstations. In 2019, the introduction of new machines that pack boxes faster than human workers generated media attention as “a harbinger of automation,” pointing to a future “lights out” warehouse populated only by machines. Indeed, many patents do describe automatic technologies such as robotized shelves, and delivery drones are already being tested.

But most patents owned by Amazon instead describe a future in which new machines make humans work more intensely and under stricter surveillance. This has been capitalism’s wet dream for two centuries: using machinery in ever more efficient ways to better control and squeeze value out of workers. Patents are indeed quite explicit about the expectation for the continuous presence of workers on an increasingly automated warehouse floor. A patent for a modular inventory system describes automation as “expensive and time-consuming to implement, unlike a human workforce, which can be allocated according to need. For that reason, conventional inventory systems continue to utilize personnel for many… tasks.” Yet the relationship between an inexpensive workforce and the costly machines they will interact with may be in for a change.

In many patents, Amazon designs systems in which workers serve automation rather than using it. Workers are to carry a plethora of digital sensors, often incorporated in wearable devices such as bracelets or glasses and aimed at extending software’s ability to sense the environment. Imagine wearing data-hungry devices that incorporate accelerometers, infrared sensors, cameras or microphones. Such devices can be triggered by worker activity: as sensors are able to capture the position of a worker’s hand or head, or their angle of gaze, the device can collect data in real-time as a worker moves their hand toward a shelf or looks at something.

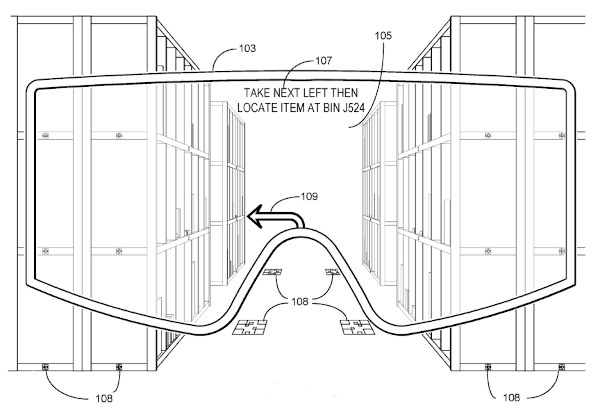

The central algorithmic systems used by management to run the warehouse can use this data to increase the efficiency of the system, for example by speeding up human labour and making it more efficient. Augmented reality goggles worn by workers walking in the warehouse to retrieve certain products would begin to “facilitate fulfilment”: the googles speed the process up by suggesting the most efficient route through arrows that appear on top of the worker’s natural visual field, for instance indicating when and where to take a turn. Other glasses analyse what a shelf a worker is looking at, generating a three-dimensional model of the available space and calculating how to store an item most efficiently.

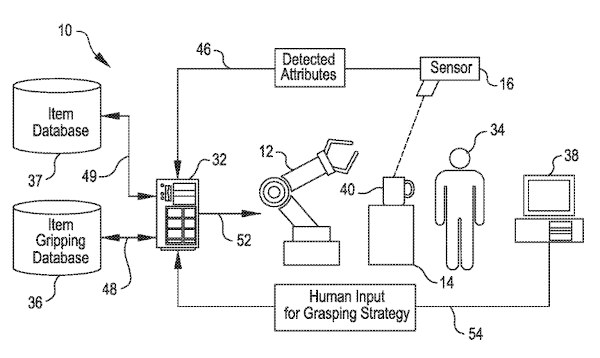

In some cases, the envisioned data capture systems would be used directly to train robots. In one set of patents, workers teach a robotic arm how to grasp a certain item (a coffee mug, for example, which is not a trivial task for a computer). The robotic arm needs a protocol of appropriate movements, pressure and timing to grab the mug without dropping or breaking it, but if a worker was required to grab the mug whilst wearing a special glove covered with kinematic and pressure sensors, a computer could analyse the hand’s movements and record the strategy used to perform the task. The worker’s embodied knowledge would thereby become incorporated in software and could immediately be used to optimise robots’ behaviour in any of Amazon’s fulfilment centres. This desire for a warehouse in which workers sense and act for algorithmic systems seems to take Karl Marx’s idea of the worker becoming an “appendage” of machinery to new heights.

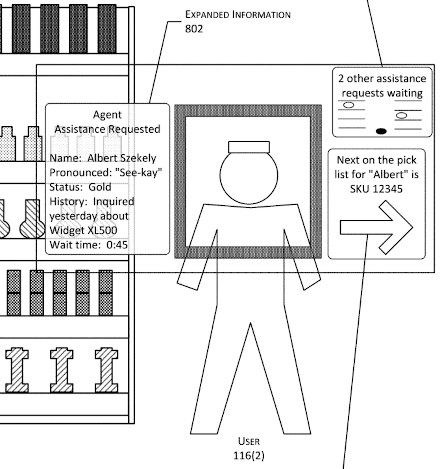

Augmented reality technology can also be used to increase worker surveillance and control. Take a patent for an “enhanced interaction system” between workers and supervisors. In collaboration with facial and clothing recognition, a software can identify a worker when a supervisor wearing an augmented reality headset looks at them, and then project relevant information onto the wearer’s visual field. The device is meant to provide demographic data about the worker, or relationships with other workers, and to make this information readily available to management, including data such as “status,” which may include the worker’s position, efficiency or future tasks.

During Amazon’s flashy re:Mars conference, organized yearly in Las Vegas to showcase prototypes and the future of the company, an Amazon executive described the future warehouse as a “symphony of humans and robots working together.” But Amazon’s patents rather seem to imagine a future workplace where domination over workers is increasingly orchestrated via technology. All this said, patents should be handled with care: there is no way to know which of them will materialize and when, which will never be developed, or which will only be used in court.

Through patents, corporations partially own a range of possible technological futures. Yet as we know, the future is unwritten – and Amazon’s patents remind us our task is to take it back. •

This article first published on the Novara Media website.