Extractivism and Exploitation in Peru

Martin Vizcarra, Peru’s president, has announced that “[t]his government has taken up the challenge and has been working on the approval of a new regulation for mining procedures in order to streamline those procedures.” The regulation “aims to provide certainty for investors in order to boost private investment” and will satisfy the demands of mining magnates who “have requested that the procedures be expedited in order to unlock mining projects and allow the sector to contribute to the economic reactivation.”

The current government decision to elevate extractivism as the engine of economic reactivation is a blessing for extractive elites who have been pushing for deregulation, a secure investment climate and a faster economic re-opening. On 20 July 2020, Carlos Gálvez, former president of mining and energy association SNMPE, said, “To recover we have to immediately activate the portfolio of mining projects, as mining will drive the entire economy.” In a similar manner, on 23 June 2020, Víctor Gobitz, the president of Peru’s Institute of Mining Engineers and executive president of local precious metals producer Buenaventura, said that “we must look at the crisis as an opportunity.”

Gobitz went on to add, “A more expeditious licensing and permit system is required,” a demand that the government has diligently fulfilled. Gobitz also made it clear that the political and social climate in Peru needed to be overhauled. While speaking on the problems of mining, he said that many mining projects “confronted social problems and were halted.” He tells the interviewer that the root of this problem is the system “that generates local leaders without a long-term vision or a comprehensive vision of the country.” In order to stall this system, Gobitz suggests, “[i]n the long term we have to work to mature the political system, to have fewer political parties and to be more responsible with the country.”

Aggressive Extractivism

While the state and the power bloc have harmoniously merged to aggressively advance an agenda of extractivism, the working class and indigenous people have been entirely erased from the blueprint of “development.” Through the installment of new regulations aimed at intensifying mining, providing certainty for investors (eliminating resistance) and streamlining procedures (authorizing accelerated ecological damage), the Peruvian state has formally set the seal on a slow exploitation that has already been going on for a long time. Even before the present-day governmental announcements, Peru had been witnessing the onslaught of “economic reactivation.”

This ruthless reactivation started in June when mining companies decided to operate at 80% of production capacity by the end of June. To achieve this production level, mining companies reworked shift patterns and started testing the workers for COVID-19 at the sites. Meanwhile, unions for mine workers opposed this production plan and “voiced concerns that some planned shifts are too long while testing and protective measures need to be strengthened.” Jorge Juárez, leader of Peru’s mining and steel workers’ federation, stated, “Rapid tests [at mining sites] aren’t reliable, so we want molecular tests that give more accurate diagnosis.”

As predicted by Jorge Juarez, mining sites became new hubs of infection as corporations intransigently insisted on maintaining “operational continuity” and reviving the economy. At the Santander mine operated by Canada’s Trevali Mining, 30% of the total workforce tested positive for COVID-19. Hochschild, a London-based corporation, halted its operations at the gold and silver Inmaculata mine after a number of workers tested positive. Despite the obvious endangerment of mine workers that is taking place, the government has chosen to casually coerce the workers into reactivating the economy, and Peru’s Energy and Mines Minister Susana Vilca has said that the country’s mines will resume operating at 100% production capacity by the end of July.

Indigenous Resistance to Mining Operations

The programme of merciless mining has not gone unopposed, and even during the COVID-19 pandemic, resistance is amplifying. Since July 15, the people of Espinar province have been protesting against the Swiss company Glencore, which owns the Antapaccay mine, and recently, protestors torched two vehicles coming from the Las Bambas mine to draw attention to their plight. In Espinar, the residents presented “a proposal that consisted of delivering food vouchers, medicines, and biosecurity equipment against COVID-19 and microcredits at zero percent interest.” Through the Espinar Framework Agreement, Glencore was duty-bound to financially support the Espinar people “under conditions of a humanitarian emergency.” Now, the company is refusing to help the people and on a “technical basis,” has concluded that the demands of the Espinar residents are null and void.

The technical basis on which Glencore is predicating its arguments is starkly inhumane. As per the Espinar Framework Agreement, Glencore is supposed to help in sustainable development, and the contribution of 3% of profit before tax to a community fund is a primary modality for doing so. This 3% contribution, instead of a being a wholehearted attempt at improving people’s livelihoods, is a strategic method of defusing class struggle. The annual revenue of the Antapaccay mine is $1.15-billion, and the net worth of Ivan Glasenberg, the CEO of Glencore, is $5.4-billion. In comparison to these astronomic figures, 3% is next to nothing.

Through a narrow focus on the 3% profit contribution, Glencore is saying that it is “technically” not obliged to help the people of Espinar escape from the coronavirus-caused deaths and misery. The audacity with which Glencore is rebuffing the people’s demands derives from the strong protection the state guarantees to any mining initiative. Companies like Glencore can authoritatively air-brush the oppressed because they know that the state is on their side and will help in obfuscating demands and crushing mutinies.

From the Espinar case, we also observe how corporatist arrangements, being entirely devoted to capital accumulation can’t compromise their “technical integrity” even to save innumerable people from death. Furthermore, the incalculable suffering and damage that the Antapaccay mine has brought to Espinar province morally and legally binds Glencore to pay reparations to the people and end its destructive operations.

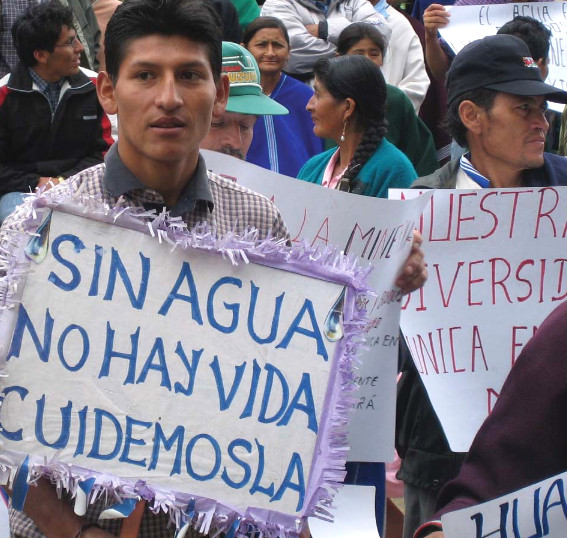

According to a report entitled “Diagnosis of Human Environmental Health in the Espinar-Cusco Province,” the people living in the region had detectable levels of the following four toxic materials in their body: arsenic, mercury, lead and cadmium. The presence of lead, in particular, is highly worrying because it has been found that “[e]xposure to lead can seriously harm a child’s health, including damage to the brain and nervous system, slowed growth and development, learning and behavior problems, and hearing and speech problems.” On top of the direct degradation of human health, mining in Espinar has contaminated “surface waters and sediments of the Camacmayo, Tintaya and Collpamayo waterways.”

Mass protests in Espinar against the adverse impacts of mining had begun as early as 2000 when BHP Billiton was operating in the region. Through these protests the people of Espinar were able to establish a Framework Convention, an agreement that later proved to be entirely ineffectual. In 2006, Xstrata took over BHP Billiton’s mining activities and soon started receiving complaints from the locals, who stated that mining activities were resulting in the births of deformed animals. These complaints went unheeded by the company.

Unconcerned about anything, Xstrata continued to ceaselessly pollute the region, and as reports started coming in of the company’s involvement in the degeneration of Espinar’s ecosystem, the people finally chose to stage an indefinite strike. In response to these strikes and protests, the state used its emergency powers to disperse the blockade of Tintaya mine and quell incipient demonstrations. During the emergency, the state deployed 1500 police officers of the Peruvian National Police (PNP) in the region, and these “public security forces were illegally detaining and mistreating 22 civilians in the Tintaya Marquiri mine site, including women, minors, and two human rights workers… Later, the illegal detainees were freed – claims that they suffered torture while under detention were not investigated, however, the government preferring to charge them with terrorist offences.”

At the end, three protestors were killed and 12 were severely wounded. In 2017, villagers from the area adjacent to the mine where violence took place told the UK High Court “that Xstrata gave the PNP logistical assistance, including equipment and vehicles, encouraged the PNP to mistreat the protesters, and that Xstrata failed to take sufficient measures to prevent human rights violations.” At the behest of Xstrata, PNP “used excessive force including the use of live ammunition, beat and kicked protesters, subjected them to racial abuse and made them stand for prolonged periods in stress positions in the freezing cold.”

In 2013, Glencore acquired the mining projects of Xstrata by absorbing the latter through a takeover. While the Tintaya copper mine closed down in 2013, a new Antapaccay mining project, started in 2012, compensated for its closure. Antapaccay mine’s production consists of 80,000 tons of copper per day. Its visible environmental impacts include “Biodiversity loss (wildlife, agro-diversity), Soil contamination, Waste overflow, Groundwater pollution or depletion, Large-scale disturbance of hydro and geological systems.” Protests have occurred against Glencore’s Antapaccay mine, and on “27 March 2015, two thousand affected inhabitants of Espinar peacefully protested against the mining operations. They asked the Peruvian government to establish the cause of the contamination and to address the water pollution.”

Like Xstrata, Glencore has turned a deaf ear toward the community and is continuing to mine copper in an environmentally unsustainable way. In December 2018, Cusco Regional Health Directorate (DIRESA) published a report stating that a high level of metal contamination had been found in potable water. Correspondingly, in February 2019, the Regional and Municipal Councils of Espinar declared a health emergency for 90 days, and the governor of Cusco was asked to cooperate with the Ministry of Health and Environment to redress this problem.

Despite DIRESA’s report that the water sources in Espinar region are contaminated, a “technical table,” comprising various technocratic and non-elected components of the state apparatus, has concluded that the drinking water in the Espinar province is still suitable for human consumption. This shows the extent to which Glencore enjoys state protection and is able to mould governmental departments to create a stable “investment climate” in which the contradictions of class struggle have been explosively contained for a period of time.

Besides state protection, Glencore is also utilizing regularized violence to facilitate its mining operations. In late December 2018, Liderman, the security company hired by Glencore, attacked the Alto Huarca community and specifically targeted women. In April 2018, a number of police officers and 8 officials of the Glencore Antapaccay mine, numbering 40 in total, intimidated and used coercive methods against the Alto Huarca community living in the Yauri district. The aim was to evict the community from their own lands and enable the planned expansion of mining projects.

The Looming Water Crisis

Peru’s government, by choosing to speed up the mining sector, has spurned OHCHR’s (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights) key recommendations that asked governments to ensure “indigenous territorial protection and the health of indigenous peoples during the pandemic by considering a moratorium on extractive mining, oil, and logging activities.” Through a mining-led offensive against indigenous people, Peru is slated to provoke an enraged indigenous opposition.

The current deregulation of the mining sector bears an extremely frightening resemblance to what an adviser of a former minister of energy and mines said a few years back: “We have to be practical … you cannot … [conduct] consultations everywhere. That is stupid. It only creates chaos, disorder, lack of governability.” By deregulating the mining sector and expediting procedures, the current government is giving the message that mining can’t be impeded by the unreasonable demands of indigenous people.

Moreover, by normatively linking the weakening of procedures to the positively framed notion of “economic reactivation,” the administration is culturally colonizing the indigenous people through a rationalized-economic ideology. Alan Garcia, the former president of Peru, had once said that “there are millions of hectares of forests that are idle, millions of hectares that communities are not farming … there are many resources that … do not receive investments and not produce jobs.

And all of this is due to the taboo of old ideologies, laziness, intolerance or the law of the dog in the manger: If I do not use it, no one will.” He had later added that “[We] must defeat the absurd pantheistic ideologies that believe that walls are gods, that the air is god, the return to these primitive forms of religion, where they say do not touch that mountain because it is an apu [God] and full of a millenarian spirit… That we are advancing does not mean that all our ancient forms of thought have been overcome.”

While not overtly crude like Alan Garcia, the present government is advancing a similar agenda of anti-indigenous development by ideologically intertwining economic reactivation with the violence of extractive capital. In a manner reminiscent of the National Development Plan “Peru Toward 2021,” Vizcarra’s government has embarked on a neocolonial civilizing mission. The aforementioned plan, developed by the National Centre for Strategic Planning (CEPLAN), stated its objective of “overcoming the culture of ‘limited good’ and ‘equalizing downward’ which are the vestiges of a culture of underdevelopment that hinders productive and inclusive modernization.” The present-day government, too, is attempting to modernize the indigenous people and thus, rob them of their existence.

In addition to indigenous resistance, Peru is likely to witness a general uprising of the oppressed, with water scarcity acting as a catalyzing factor. Through the lethal legalization of intensified mining, the state is exacerbating an already acute water crisis caused by “water extractivism.” Water extractivism is defined as “the practice to singularise and standardise water into the category of ‘resource’ in order to master it and extract as much economic value from it as possible.” With the buttressing of the mining sector, water extractivism and the consequent scarcity is set to aggravate. It is estimated that “every year, mining and metallurgy release over 13 billion cubic meters of effluents into Peru’s water courses.” Due to this water contamination, many Peruvians are suffering from fatal diseases, and in the Central Andes, for instance, the contamination of rivers by arsenic and other heavy metals is causing carcinogenic diseases among Peruvian adults and children. Tragically, “children are most vulnerable to acute and chronic effects of heavy metal and arsenic intake. This is due to the fact that children consume more water per unit of body weight than adults.”

Rondera Bianca, a female activist living in El Tambo, Peru, beautifully expresses the heart-rending existential impacts of mining on children:

Ourchildren tell us

Mamita, I want to live

Throw out the miners

Because I don’t want to die

I tell my children

That’s why I’m going to fight

So that they can have life

And water to drink

To Peru and the whole I want to ask

That they respect our rights

Instead of being spatially confined to the rural regions, mining-induced water scarcity is a phenomenon that also afflicts the urban areas. Lima, for example, is the second driest capital in the world after Cairo, receiving “less than an inch of rain per year and relying on three rivers for potable water.” The three rivers on which Lima relies, the Rimac, Lurin and Chillon, have all been contaminated by mining operations. It has been found that 60% of contamination in the Rimac River is due to mining activities. Similarly, uncontrolled garbage disposal and heavy metal contamination by the extractive sector have polluted the Chillon River where “12 times the maximum permissible levels of pollutants for drinking water” were found. In the Lurin River, water contamination has reached such an extent that the water has to be boiled before consumption. In 2013, Peru’s Ministry of Environment, as a late acknowledgement of the role of mining in contaminating the Lurin River, announced a plan of multi-level governmental coordination to specifically manage mining as a major polluting source.

As Peru’s government stirs the hardships of the COVID-19 pandemic in the authoritarian amalgam of extractivism, a new volatile mixture of resistance is being created. In the current period, the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the utterly undisguised rapacity of mining companies and has sharpened the edges of class struggle.

Using Pablo Neruda’s words, one can say that Peruvian workers and indigenous people are realizing that extractivism “crushes them, covers them with malignant spittle, casts them out to the roads, murders them with police,… imprisons them, spits on them, buys a treacherous president who insults and persecutes them, kills them with hunger on the plains of the sandy immensity.” With this realization, a working class-indigenous alliance is being constructed, vowing to revolt against the extractive elites. •