Racism, COVID-19, and the Fight for Economic Justice

While the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests sweeping the United States were triggered by recent police murders of unarmed African Americans, they are also helping to encourage popular recognition that racism has a long history of punishing consequences for black people that extend beyond policing. Among these are the enormous disparities between black and white well-being and security. This post seeks to draw attention to some of these disparities by highlighting black-white trends in unemployment, wages, income, wealth, and security.

A common refrain during this pandemic is “We are all in this together.” Although this is true in the sense that almost all of us find our lives transformed for the worst because of COVID-19, it is also not true in some very important ways. For example, African Americans are disproportionally dying from the virus. They account for 22.4 per cent of all COVID-19 deaths despite making up only 12.5 per cent of the population.

One reason is that African Americans also disproportionally suffer from serious pre-existing health conditions, a lack of health insurance, and inadequate housing, all of which increase their vulnerability to the virus. Another reason is that black workers are far more likely than white workers to work in “front-line” jobs, especially low-wage ones, forcing them to risk their health and that of their families. While black workers comprise 11.9 per cent of the labor force, they make up 17 per cent of all front-line workers. They represent an even higher percentage in some key front-line industries: 26 per cent of public transit workers; 19.3 per cent of childcare and social service workers; and 18.2 per cent of trucking, warehouse, and postal service workers.

Unemployment

African Americans have also disproportionately lost jobs during this pandemic. The ratio of black employment to adult population fell from 59.4 per cent before the start of the pandemic to a record low of 48.8 per cent in April. Not surprisingly, recent surveys find, as the Washington Post reports, that:

“More than 1 in 5 black families now report they often or sometimes do not have enough food – more than three times the rate for white families. Black families are also almost four times as likely as whites to report they missed a mortgage payment during the crisis – numbers that do not bode well for the already low black homeownership rate.”

This pandemic has hit African Americans especially hard precisely because they were forced to confront it from a position of economic and social vulnerability, as the following trends help to demonstrate

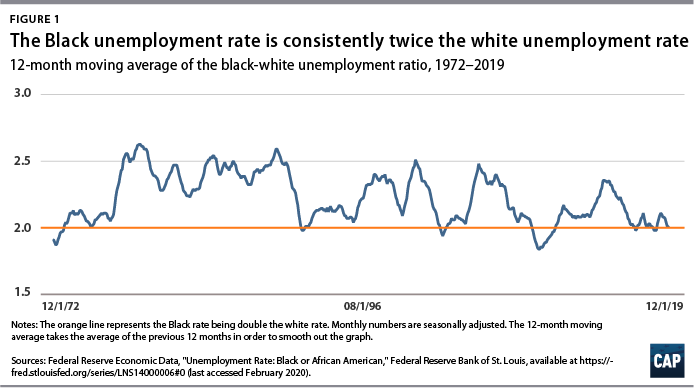

The Bureau of Labor Statistics began collecting separate data on African American unemployment in January 1972. Since then, as the chart below shows, the African American unemployment rate has largely stayed at or above twice the white unemployment rate.

As Olugbenga Ajilore explains:

“Between strides in civil rights legislation, desegregation of government, and increases in educational attainment, employment gaps should have narrowed by now, if not completely closed. Yet as [the figure above] shows, this has not been the case.”

Wages

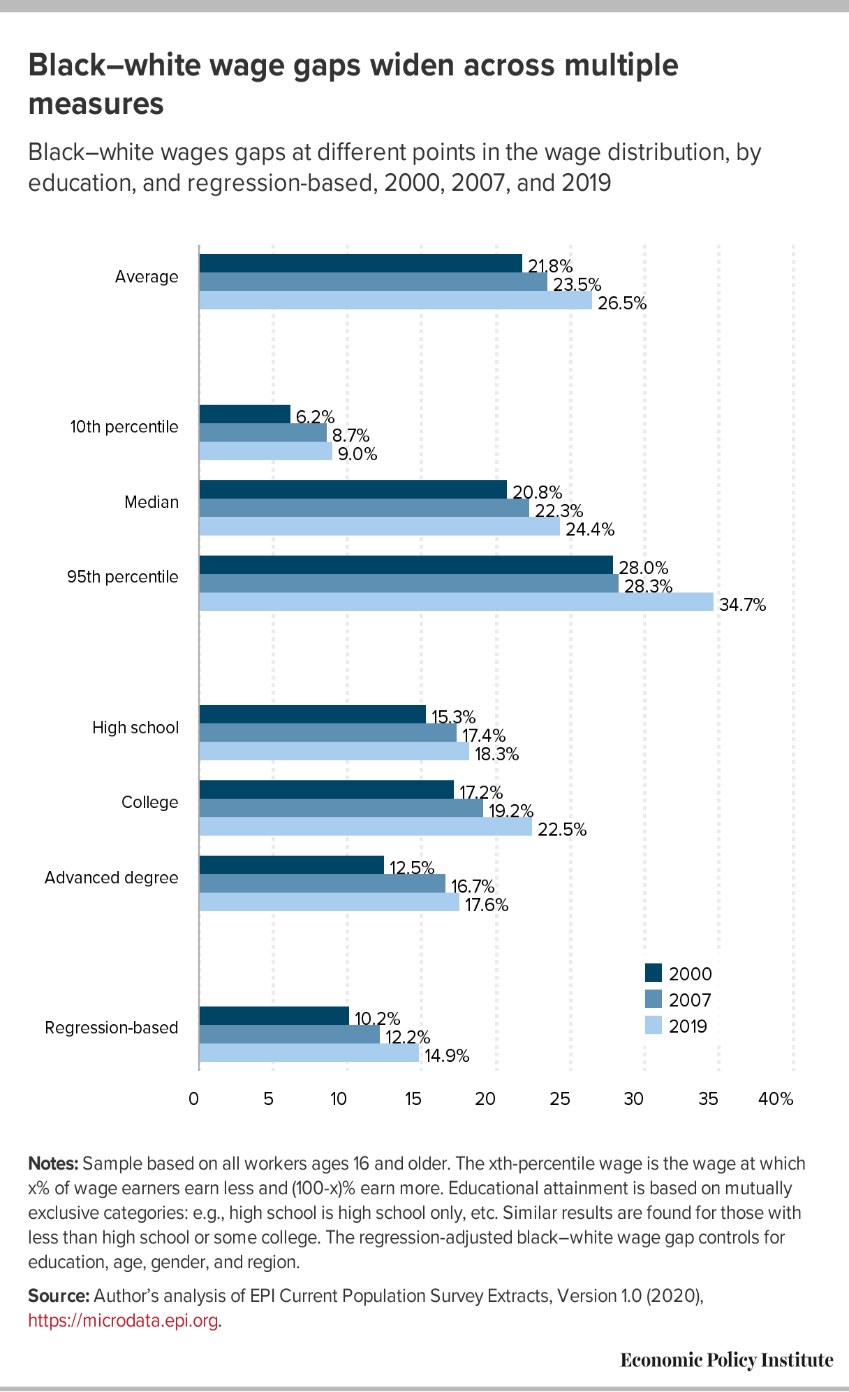

The “Black-white wage gap” chart below from an Economic Policy Institute study shows the black-white wage gap for workers in different earning percentiles, by education level, and regression-adjusted (to control for age, gender, education, and regional differences). As we can see, the wage gap has grown over time regardless of measure.

Elise Gould summarizes some important take-aways from this study:

“The black-white wage gap is smallest at the bottom of the wage distribution, where the minimum wage serves as a wage floor. The largest black-white wage gap, as well as the one with the most growth since the Great Recession, is found at the top of the wage distribution, explained in part by the pulling away of top earners generally, as well as continued occupational segregation, the disproportionate likelihood for white workers to occupy positions in the highest-wage professions.

“It’s clear from the figure that education is not a panacea for closing these wage gaps. Again, this should not be shocking, as increased equality of educational access – as laudable a goal as it is – has been shown to have only small effects on class-based wage inequality, and racial wealth gaps have been almost entirely unmoved by a narrowing of the black-white college attainment gap … And after controlling for age, gender, education, and region, black workers are paid 14.9% less than white workers.”

Income

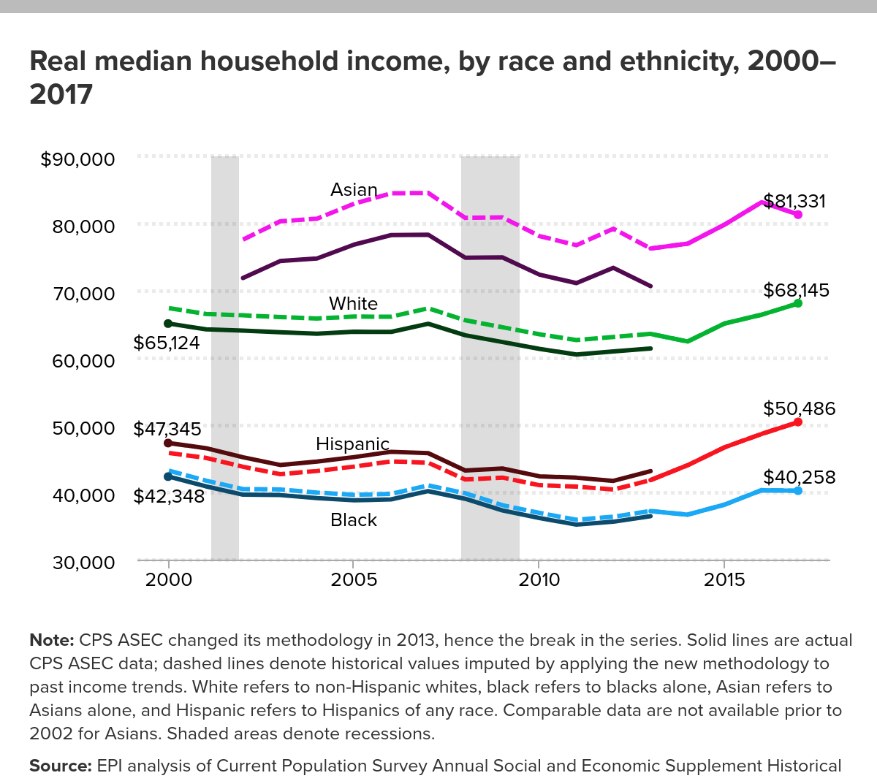

The next chart below shows that while median household income has generally stagnated for all races/ethnicities over the period 2000 to 2017, only blacks have suffered an actual decline. The median income for black households actually fell from $42,348 to $40,258 over this period. As a consequence, the black-white income gap has grown. The median black household in 2017 earned just 59 cents for every dollar of income earned by the white median household, down from 65 cents in 2000.

Moreover, as Valerie Wilson, points out, “Based on [Economic Policy Institute] imputed historical income values, 10 years after the start of the Great Recession in 2007, only African American and Asian households have not recovered their pre-recession median income.” Median household income for African American households fell 1.9 per cent, or $781, over the period 2007 to 2017. While the decline was greater for Asian households (3.8 per cent), they continued to have the highest median income.

Wealth

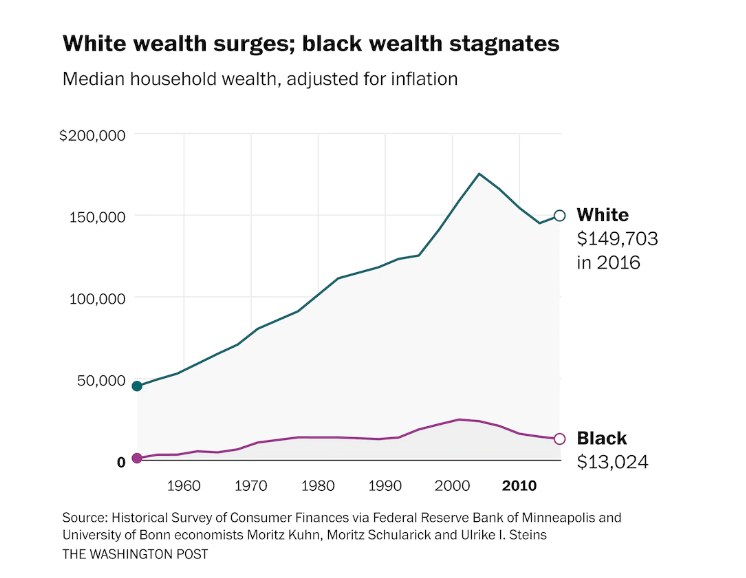

The wealth gap between black and white households also remains large. In 1968, median black household wealth was $6,674 compared with median white household wealth of $70,768. In 2016, as the chart below shows, it was $13,024 compared with $149,703.

As the Washington Post summarizes:

“‘The historical data reveal that no progress has been made in reducing income and wealth inequalities between black and white households over the past 70 years,’ wrote economists Moritz Kuhn, Moritz Schularick and Ulrike I. Steins in their analysis of US incomes and wealth since World War II.

“As of 2016, the most recent year for which data is available, you would have to combine the net worth of 11.5 black households to get the net worth of a typical white US household.”

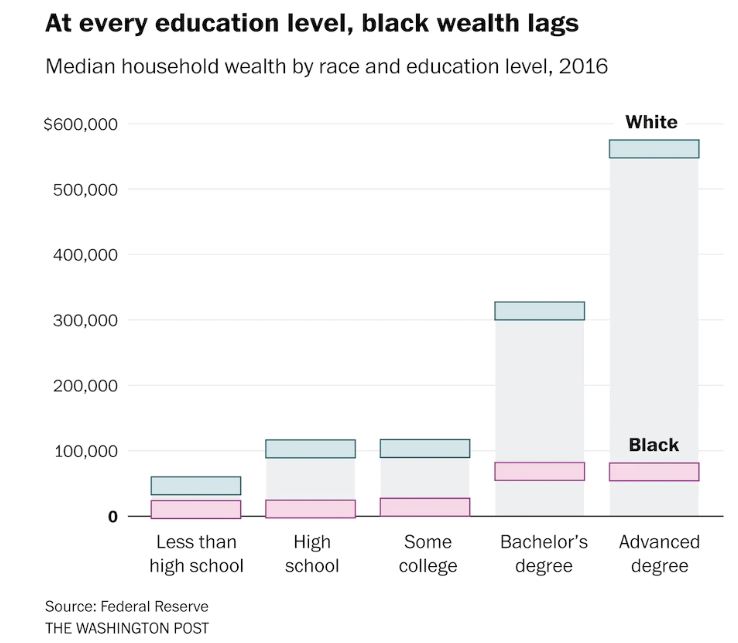

The self-reinforcing nature of racial discrimination is well illustrated in the next chart. It shows the median household wealth by education level as defined by the education level of the head of household.

As we see, black median household wealth is below white median household wealth at every education level, with the gap growing with the level of education. In fact, the median black household headed by someone with an advanced degree has less wealth than the median white household headed by someone with only a high school diploma. The primary reason for this is that wealth is passed on from generation to generation, and the history of racism has made it difficult for black families to accumulate wealth, much less pass it on to future generations.

Security

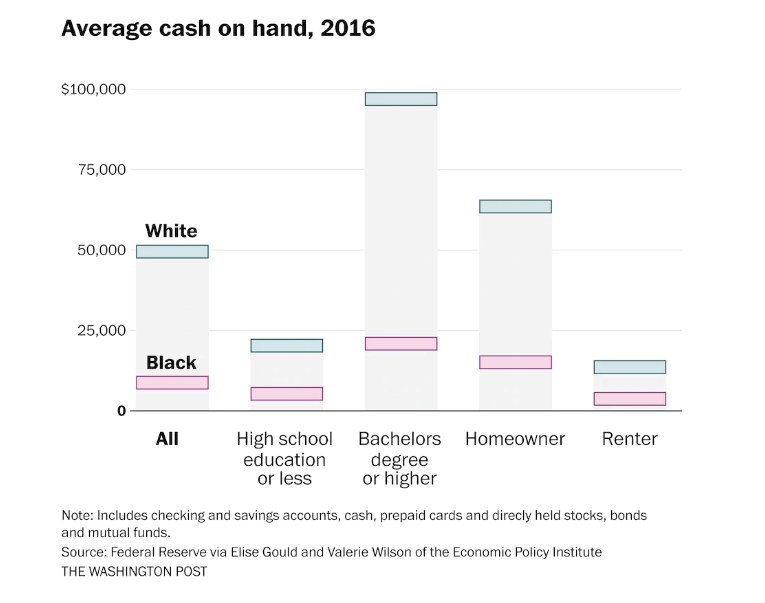

The dollar value of household ownership of liquid assets is one measure of economic security. The greater the value, the easier it is for a household to weather difficult times, not to mention unexpected crises, such as today’s pandemic. And as one might expect in light of the above income and wealth trends, black households have far less security than do white households.

As we can see in the following chart, the median black household held only $8,762 in liquid assets (defined as the sum of all cash, checking and savings accounts, and directly held stocks, bonds, and mutual funds). In comparison, the median white household held $49,529 in liquid assets. And the black-white gap is dramatically larger for households headed by someone with a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Hopeful Possibilities

The fight against police violence against African Americans, now being advanced in the streets, will eventually have to be expanded and the struggle for racial justice joined to a struggle for economic justice. Ending the disparities highlighted above will require nothing less than a transformational change in the organization and workings of our economy.

One hopeful sign is the widespread popular support for, and growing participation in, the Black Lives Matter-led movement that is challenging not only racist policing but the idea of policing itself and is demanding that the country acknowledge and confront its racist past. Perhaps the ways in which our current economic system has allowed corporations to so quickly shift the dangers and costs of the pandemic onto working people, following years of steady decline in majority working and living conditions, is helping whites better understand the destructive consequences of racism and encouraging this political awakening.

If so, perhaps we have arrived at a moment when it will be possible to build a multi-racial working class-led movement for structural change that is rooted in and guided by a commitment to achieving economic justice for all people of color. One can only hope that is true for all our sakes. •

This article first published on the Reports from the Economic Front blog.