The Far Right, Racism, and the Universities

Memories of Western, Kenneth Hilborn, and the Politics of Opposition

Marx wrote presciently in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852) that “The tradition of all the dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brain of the living.” Our current period is truly one of many bad dreams.

Slavery’s horrors and state policies of ‘Indian’ subjugation have universities apologizing for their 18th-and-19th century complicity in the transatlantic trade in human flesh and an historical association dropping the name of a Prime Minister from its annual book prize in response to research uncovering genocidal practices. Statues commemorating ‘great white men’ of the past have been removed from places of prominence, their eminence now tarnished by revelations of bad acts that were once regarded in ruling circles as paving stones on the roadway to progress. Apologies abound; reconciliations are promised; reparations even spoken of from the podiums of would-be candidates for the highest of bourgeois political office.

The COVID 19-cancelled 99th-annual meeting of the Canadian Historical Association was supposed to have taken place at London, Ontario’s Western University, 1-3 June 2020, and to be focussed on the theme of addressing anti-Black racism. This unleashed something of the torment of the university’s dead generations, although they were not all that long buried. Racism at Western figured decisively in a series of posts on Active History, a website animated by left-liberal progressive politics seeking to connect historians to larger publics, build “community” among historians, and develop recognition of the responsibilities of historians.

Communications by Asa McKercher and Will Langford address, among other things, the University of Western Ontario’s (UWO) association with professors assailed for professing racist views, especially the Psychology Department’s Philippe Rushton, who gained notoriety in 1989 with his right-wing funded research on racial hierarchies of intelligence, and the more obscure case of the Department of History’s Kenneth Hilborn, whose main purchase on fame was his stock-market fueled personal fortune. Hilborn, who taught at UWO from 1961-1997, died in 2013, leaving Western a hefty $1,000,000. Much of this ($750,000) went to the History Department, where it was carved up into student awards bearing Hilborn’s name, an act of commemoration that McKercher and Langford raise questions about and which the current Department Chair, Francine McKenzie, answers by stating that the financial support offered Western’s History undergraduates and graduate students has nothing to do with any of the views of their benefactor.1 The dream of dollars/the nightmare of nullification.

Reading these commentaries, I was taken back to my brief stint as a University of Western Ontario undergraduate, a time when I had some minor dealings with Kenneth Hilborn, and was a part of a mobilization to oppose him. These memories address London, an environment in which I witnessed significant racism, and Hilborn’s significance, focussing on how the left can best challenge views it finds repugnant. They recall something of what it was like struggling to become a leftist in the London and Western of the very early 1970s, and offer some cautions about how quick we are to jettison commitments to academic freedom and freedom of speech.

What follows provides an introduction to Kenneth Hilborn, an obscure figure at best, whose place in Canadian academic culture of the 1960s tells us how much universities have changed over the years. This is followed by a brief commentary on London, Ontario, which has proven to be an environment in which fringe right-wing thought has often incubated. I then close with a discussion of opposition to Hilborn, and my reflections on that.

Kenneth Hilborn: Scholarly Silence and Money’s Final Loud Talk

Kenneth Hilborn published next to nothing in terms of scholarship, although he was a professor for more than 35 years. An idiosyncratic ideologue and an awkward colleague, Hilborn was born to academic life and seemed to regard his place within it as an entitlement. To the extent that he is known today, it has nothing to do with research and writing, and everything to do with his funding of various student awards at Western and internships elsewhere. The extent and nature of his bequests to various institutions are still not fully detailed, but enough is known to offer preliminary comment.

By my rough count, Western’s History Department offers as many as twelve stipends bearing Hilborn’s name, bundled within six different undergraduate/graduate awards, scholarships, and internships. The annual undergraduate bursaries include five offered @ $2000 and three @ $1000. The graduate awards are more lucrative, encompassing two @ $6250, one @ $5000, and an unlimited number of travel awards to a total of no more than $8000 annually. These constitute a significant number of the Department’s student offerings, and it could well be joked that it must be difficult for a student to pass through Western’s programs and not be on the receiving end of funds graced with Hilborn’s name. It is somewhat odd, if not unfortunate, that no other former faculty member comes anywhere close to having their name associated with this quantity of benevolence. Money, of course, talks. But this loudly?!

There is something clearly wrong, in my sense of how the world should operate, that Fred Landon, a prolific author and distinguished, imaginative figure who played an important role in writing the history of Western Ontario (as well as being the University’s librarian and fulfilling many other administrative posts) has an annual $375 stipend associated with his name, while Hilborn’s recognitions in this area are so much more. No socialist, to be sure, Landon was, nonetheless, a pioneering social historian with an almost unheard of interest in subjects rarely addressed during his early tenure as a UWO professor, including appreciation of the role of the “common man” in the Upper Canadian rebellion of 1837-1838.2

Landon studied with Ulrich B. Phillips at the University of Michigan. Phillips was a historian of slavery in the American South whose works would now be condemned as racist, but who collaborated with John R. Commons in the multi-volume Documentary History of American Industrial Society (1910-1911). Landon helped make the history of blacks in Canada accessible, and took an interest in how labour figured centrally in society’s development. Landon had an especial interest in the Knights of Labor and encouraged MA students he was supervising at UWO in the 1930s and 1940s to explore the Order’s history, which he commented on with insightful speculation.3

I have no knowledge of how Hilborn came to embrace the political views that he did but, like so many of his contemporaries, he was somewhat to the academic manor born. His father was a Professor of Romance Languages, teaching at Acadia from 1927-1950 and then heading the Department of Italian and Spanish at Queen’s University from 1950 until his retirement in 1966. Hilborn’s gift to Western funded not only the History Department student awards, but also scholarships in the Spanish Department, named after Hilborn’s parents. The Marguerite and Harry W. Hilborn entrance scholarships for graduate and undergraduate students in the Spanish Department encompass two awards @$4500 and one @ $1000. Other institutions also benefitted from Hilborn’s largesse, including the Fraser Institute, a right-wing think tank domiciled in Vancouver, which was gifted over $750,000 and established the Kenneth Hilborn Internship.

Critics of these named scholarships want some kind of self-conscious reflection of the Department about what Hilborn believed, addressing why such views were and remain repugnant. The Department has determined to continue offering all of the scholarships carrying Hilborn’s name. Its commitment to interpreting commemoration and how it manifests itself in public history is what the Department deems necessary with respect to any issues arising from Hilborn’s legacy. But this has only been posed in the abstract. Will a public history course at Western devote a session or two to a reading of some of Hilborn’s writings, confined as they largely are to ideological tracts, assessing how Western and its History Department came to place his name on a significant number of scholarships, and whether this relates to, or is different than, recent controversies about public monuments and academic prizes bearing the names of historical figures whose past acts have now come to be questioned? That might prove pedagogically interesting. For those who want Hilborn’s history to be confronted, this could be a beginning.

Hilborn’s career, such as it was, is perhaps best measured by his teaching. His classes were apparently well attended, focussing on international relations. A course in totalitarianism was Hilborn’s signature offering, comparing, of course, Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union. Western’s announcement of the Hilborn legacy places an accent on his regard for the university’s students. Critics of the Hilborn awards have not addressed this issue at all. But it is surely central.

Is there any evidence that Hilborn discriminated against students who opposed his views, or marked student papers and assignments unfairly if they put forward positions antithetical to his right-wing politics? It is clear that Hilborn attracted students who embraced the politics of the right and that he became, over time, their defenders against the nefarious ‘left’ professoriat, a component of which Hilborn would have tossed to the wolves of academic dismissal for fairly innocuous – if a tad cavalier – comments on undergraduate papers. This alone suggests that his commitment to academic freedom was superficial, little more than skin deep.4 Hilborn was not shy about confronting his opponents in public forums and meetings, his demeanour aggressive, striving for intimidation. Whether this defiance and overbearing posture was part of his classroom persona is not something that I have been able to ascertain.5 It would be intriguing to know if Department or University records contain instances of students alleging prejudicial conduct.

Scholarly publication was clearly not high on Hilborn’s agenda. He probably secured his University of Western Ontario (UWO) appointment on the sole basis of an Oxford PhD supervised by A.J.P. Taylor, completed in 1960, when Hilborn was roughly 25 years old. Tenure did not exist at Western in the 1960s, and when it did come sometime very early in the 1970s, anyone who had been around for a few years was grandfathered in. Hilborn was known to talk of Departmental service as part of one’s academic obligation, and he clearly had a sense of collegiality rooted in a traditional conception of the university that was certainly ensconced at Queen’s, where his father taught and where Hilborn undertook his undergraduate studies.

When I was hired at Queen’s on a sessional appointment in the late 1970s, Fred Gibson – well-connected with the Liberal Party mandarinate – was a mainstay of the History Department’s graduate program, a gentleman scholar who lived in his parents’ house across the street from the History Department building. Gibson, whose main academic writing had been a 900-page Queen’s MA thesis on the Alaskan Boundary Dispute, had a personal key to the university library, frequenting the stacks when they were officially closed. He had not published a word in years. Universities were like that then, and many harboured idiosyncratic professors who, by today’s standards, would have had a great deal of difficulty securing and keeping an appointment, or avoiding an onslaught of criticism.

Professor Gibson was actually among the more conventional of the Queen’s History Department faculty who might fit this kind of profile. Most, unlike Hilborn, were not notable for their outlandish political stands, but rather, their eccentricities. One was reputed to have kept a pet skunk in a desk drawer in his office, which is charming enough, unless you were part of the cleaning staff that, emptying a garbage can in the evening, experienced a frightening encounter.

My first tenure-stream appointment at Simon Fraser University, in the early 1980s, introduced me to a glib, highly published, conservative scholar who was both a researcher of renown and a writer of polish and panache. He still lectured in his Oxford academic gown, the only instructor at the university to do so. A professor of imperial history, he offered courses on India from a perspective that would precipitate revolt today. There was a time when his syllabus declared, “The natives will not be considered,” although I think he had toned down that kind of declarative emphasis by the time I arrived on Burnaby Mountain. We got along quite well, although we disagreed about almost everything.

A largely non-publishing oddball like Hilborn slipped under the wire and was probably never really vetted by any personnel committees as to the quality or quantity of his publications. During my brief time at UWO Hilborn had written for far-right publications like Canada Month, as the contributions to Active History by Langford and McKercher document, but very few, if any, students knew much about such writing. And at this point in his career, Hilborn apparently kept his political head somewhat down, even as he cultivated ties to reactionary bodies like the Nordic Foundation and the World Anti-Communist League. Over time, Hilborn, a committed anti-communist and defender of the racist South African apartheid regime in the 1960s, came to embrace a wider right-wing agenda. An explicit commitment to the hardening New Right waited until the 1980s, when Hilborn solidified a relationship with the publishing house of the Citizens for Foreign Aid Reform (C-FAR), founded in the 1970s by the notorious white nationalist Paul Fromm. Of the handful of C-FAR pamphlets published by Hilborn over slightly more than 20 years, the titles of two convey his concerns: The Cult of the Victim: Leftist Ideology in the 90s (1998) and In the Cause of the West: Thoughts on the Past, Present, and Future of a Threatened Civilization (2010).

These brief booklets were largely published when Hilborn was no longer teaching, and they targeted everything to the left of the Reform Party that Hilborn associated with the demise of a proper world, from Bob Rae to a metaphorical Norma Rae. His particular target was equity, which brought into his sights feminists and First Nations. He liked to allude to racial differences in standardized testing, no doubt influenced by his pal Phil Rushton. An audiotape of one of his public talks was judged to be prohibited for import by Canada Customs, meaning that, in Hilborn’s own words, it had been labelled “hate propaganda.”6

Hilborn stumped for the unfortunately-named crusaders against “political correctness,” the Society for Academic Freedom and Scholarship (SAFS), founded at the UWO in 1992 to defend Rushton. (The SAFS centre of gravity is no longer Western, with only two of the eight-member Board of Directors being Western faculty – both professors in the Psychology Department – and half of this body coming from the west, including Mount Royal’s Frances Widdowson.) Hilborn was also affiliated with the Fraser Institute and the National Citizens’ Coalition, a somewhat secretive lobby group formed in London in the late 1960s by insurance executive Colin Brown and dedicated to bringing big government down a peg, saving the people from excessive taxation. An annual donor to the Canadian Constitution Foundation, Hilborn helped to fund its right-wing legal advocacy, some of which aimed to undercut Canada’s program of socialized medicine and strike a blow against the Nisga’a Treaty of 2000, a landmark on the road to aboriginal self-government. His was clearly a catch-all politics of the right-wing fringe.

Hilborn stumped for the unfortunately-named crusaders against “political correctness,” the Society for Academic Freedom and Scholarship (SAFS), founded at the UWO in 1992 to defend Rushton. (The SAFS centre of gravity is no longer Western, with only two of the eight-member Board of Directors being Western faculty – both professors in the Psychology Department – and half of this body coming from the west, including Mount Royal’s Frances Widdowson.) Hilborn was also affiliated with the Fraser Institute and the National Citizens’ Coalition, a somewhat secretive lobby group formed in London in the late 1960s by insurance executive Colin Brown and dedicated to bringing big government down a peg, saving the people from excessive taxation. An annual donor to the Canadian Constitution Foundation, Hilborn helped to fund its right-wing legal advocacy, some of which aimed to undercut Canada’s program of socialized medicine and strike a blow against the Nisga’a Treaty of 2000, a landmark on the road to aboriginal self-government. His was clearly a catch-all politics of the right-wing fringe.

Hilborn apparently joined the Freedom Party of Ontario, and was featured as a dinner speaker in that organization’s forum on terrorism in the aftermath of 9/11. The Forest City, by this time, had become a center of such politics of the libertarian right, and the Freedom Party, a small breakaway political current, was one expression of this.7 Freedom Party gained what little notoriety it could muster as a platform for Marc Emery’s cannabis campaigns. Unlike Emery, Ken Hilborn wasn’t cut out to be an agitator or, for that matter, a proponent of pot. But I guess he took his bows where he could get them.

Certainly an ideologue, Hilborn had his causes. But Hilborn was clearly not a mobilizing force. Less of an activist than a follower with an occasional penchant to put his pathetic thoughts down on paper and retail them at gatherings of the right, especially if they involved trips out of Canada for him, Hilborn’s politics rarely took the form of extending ranks that he envisioned as his own. I can’t see him organizing a meeting, developing a communications network of affiliates of reaction, marching in the streets, or parading public spaces with a placard. His political bromides of the far right had an audience in C-FAR circles, and Paul Fromm was happy to write the odd preface to Hilborn’s pamphlets. But the retired academic paled in significance beside other more infamous celebrants of extremist views, such as Alberta’s depraved defender of anti-semitism, James Keegstra, the Holocaust denier, Ernst Zundel, or London’s own Martin K. Weiche, a particularly odious customer.

Weiche, a self-proclaimed Nazi and titular head of the fascist movement in Canada, was born in Germany in 1921 and made his way to London in the 1950s. He soon amassed a small fortune as a contractor and developer, specializing in the construction of apartment buildings. He purchased Hyde Park acreage on the outskirts of London, and built a shrine to fascism and white supremacy, dubbed “The Berghof” because it was modeled on Adolf Hitler’s home in the Bavarian Alps. Stinking of the symbolism of the Third Reich, the estate was guarded by eagle statutes, and had a giant swastika cut into the extensive backyard lawn. Weiche enjoyed posing under a portrait of Hitler, in a room graced with a signed copy of Mein Kampf. Reputed to bankroll extreme right organizations and causes, one of Weiche’s beneficiaries was supposedly Hilborn’s publisher, Paul Fromm. When Weiche died in 2011, two of his sons and his fourth wife fell out over the division of spoils. Over the course of the next decade, “The Bergof” fell into disuse and deteriorated badly. It was a tough sell on the real estate market. Haunted by infamy, it eventually sold to buyers who, to applause from London’s Jewish community, initiated demolition in March 2020.

Weiche, a self-proclaimed Nazi and titular head of the fascist movement in Canada, was born in Germany in 1921 and made his way to London in the 1950s. He soon amassed a small fortune as a contractor and developer, specializing in the construction of apartment buildings. He purchased Hyde Park acreage on the outskirts of London, and built a shrine to fascism and white supremacy, dubbed “The Berghof” because it was modeled on Adolf Hitler’s home in the Bavarian Alps. Stinking of the symbolism of the Third Reich, the estate was guarded by eagle statutes, and had a giant swastika cut into the extensive backyard lawn. Weiche enjoyed posing under a portrait of Hitler, in a room graced with a signed copy of Mein Kampf. Reputed to bankroll extreme right organizations and causes, one of Weiche’s beneficiaries was supposedly Hilborn’s publisher, Paul Fromm. When Weiche died in 2011, two of his sons and his fourth wife fell out over the division of spoils. Over the course of the next decade, “The Bergof” fell into disuse and deteriorated badly. It was a tough sell on the real estate market. Haunted by infamy, it eventually sold to buyers who, to applause from London’s Jewish community, initiated demolition in March 2020.

If Hilborn the History Department lecturer had ties to Weiche, little is known of them, but the professorial loner had found a home in Canada’s far right. He apparently liked to pass on his scurrilous pamphlets to former colleagues, who probably walked them home inside brown paper envelopes or confined them to lower desk drawers in their offices. I doubt any of the C-FAR pamphlets made it into Department showcases of faculty publications

Having his name on scholarships is one thing, and nothing to sniff at, especially given their weight in the History Department’s portfolio of awards. Was Hilborn a Departmental “icon” after his death and legacy to the University, as Langford suggests? Icon doesn’t really fit, I think, although whatever stature Hilborn managed to attain through the scholarships bearing his name was bought posthumously. Therein lies, I suspect, the main problem. Are universities willing to sell themselves to anyone? They name buildings after magnates who give them mounds of money and whose crimes of influence probably far exceed anything Hilborn managed to accomplish, but these grand donors do so in ways that could not be tarred with the brash brush of fringe politics. It takes millions to grace an athletic center or a Business School with your name, and universities have always made it known that they are entirely open to such commerce: they make no bones about accommodating big capital. If Hilborn had offered Western $50-million, would they have bowed to name a multi-storied edifice after him? Yet, for hundreds of thousands, Western was more than pleased to have his name etched in scholarship recognition within a Department’s culture.

In the Western that I knew, Hilborn was no icon; more of an embarrassment. But he was tolerated, and then some. The University had use of people like him, who taught courses, and could be had, I expect, on the cheap, in the days before faculty unions established pay grids, and Deans or other higher ups largely determined levels of annual compensation. The essentially gentleman’s club that was the UWO History Department in the 1960s and early 1970s (and it was certainly not alone in this character) may not have looked in the mirror of its liberal tolerance.

Unease about discriminating against any academic because of their political views was intense at the time, memories of McCarthyite witch-hunts still vivid. Canadian cases of professors dismissed or disciplined for their unpopular views and willingness to buck university administrations that saw it as their Trumpian right to expect proclamations and practices of ‘loyalty’ would, to be sure, have been on UWO faculty minds. The attacks on University of Toronto professor Frank Underhill, or the infamous case of Harry Crowe at United College, University of Winnipeg, may have been familiar to many at the time Hilborn was hired and throughout the 1960s, when he sustained his appointments through Administrative renewals. It is even possible that some of the UWO History Department faculty in the 1960s would have known about the fate of Louis Aubrey Wood. A distinguished Full Professor who had been appointed Head of both the Departments of History and Economics, Wood was run out of UWO decades earlier, almost certainly because of his maverick political views and willingness to rock the academic boat that university leaders considered their private helm.8 He subsequently wrote an important book, The History of Farmers’ Movements in Canada (1924). UWO History Department personnel would not have wanted to see someone’s contract renewal scotched because their views were out of alignment with majority thought.

How ironic, then, that the sufferings of the liberal left would end up insulating a non-publishing crank right-winger from close academic scrutiny. The later arrival of faculty unions and associations, in a further irony, protected the jobs and rights of people like Hilborn as well as their economic interests. You cannot build institutions premised on collective rights and exclude individuals you happen not to like, any more than you can dictate their thinking.

But still, what does it tell us that Hilborn managed to get promoted to Associate Professor, which he apparently attained by the early 1970s, when any sustained assessment of his publication record would surely have raised eyebrows about his lack of scholarly output? What are we to make of the fact that Hilborn was subsequently appointed Director of the Department’s Graduate Program, serving two terms in the 1970s? Or that he was elected to both the UWO Senate and the Executive of the Faculty Association in the mid-1990s. One might sigh, ‘those were the days’. They paved the path to later times, when Hilborn’s designation as a “Professor Emeritus of the University of Western Ontario” was associated with, and perhaps lent credence to, ideas and organizations of the fringe right, known to champion a politics of vile racism and other unsavoury positions.

Growing Up London: The Racism at the End of the Underground Railroad

As the above might well suggest, London, Ontario, proved a fertile environment for the politics of the right-wing fringe in the late 20th century. It was also a very white place in the 1950s and 1960s of my childhood and adolescence. London had a black population, of course, but before the mass immigration from the West Indies, its numbers were not large. As a teenager in the mid-to-late 1960s, I ended up knowing the younger generation of some of the black families of the town, the rallying point of their elders being the Bethemanuel Baptist Church. I grew up watching Gabby Anderson, the London Majors star outfielder in the Intercounty League, a team that was run as a players’ cooperative for a time. Part of a large family, some of whom had played in the Negro Leagues south of the border, Anderson was a local sports celebrity in London. Well-liked, he seldom complained of racism. But his children’s African-Canadian friends could have told of waking up in the middle of the night to see a cross burning on their front lawn.

London was as close to Detroit as it was to Toronto. Culturally, the terms of trade ran as much to the west as to the east. The music of choice during my teenage years was rhythm and blues, soul, Motown, and the rock associated with these genres, such as that of the Rolling Stones or the Animals. The Wonderland Pavillion, overlooking the Thames River, was where we congregated to see bands from Detroit, such as the Funkadelics. My father’s musical tastes ran to Fats Domino and Mitch Rider and the Detroit Wheels, in spite of his profound racism. Around television sets in our household, it was commonplace to see crocodile tears shed for ‘the poor blacks from Detroit’, whose neighbourhoods went up in flames during the ghetto rebellions of the 1960s. Yet not too far beneath the surface of this seeming sympathy, racism was ever-present. It flared its nostrils when peoples of colour actually threatened to encroach on territory understood to be the terrain of whites and their prerogatives, which demanded a certain social distancing. The notion that blacks – or Jews – would belong to the country clubs where I caddied and golfed in the late 1950s and early 1960s was preposterous.

Race ushered me into radicalism. It was clear to me that London, a metropolitan center at the end of the underground railroad rural hamlet of Lucan, and not far from its formal terminus in Dresden, accepted blacks in small numbers as long as their social integration was limited. It was not so much a case of segregation in housing and schooling, as in the United States, where African Americans existed in numbers that made their totalizing social suppression obvious in the formal restrictions on touchstones of everyday life. No such mass black population threatened white London, and so, the limitation was more informal. It would be exercised as constraint on intimate encounters of friendships, opportunities, and mobility, voiced in a persistent rhetoric of racism. This undercurrent of denigration and debasement has had a long life, continuing into the 21st century, as Eternity Martis chronicled in her provocatively entitled Vice article, “London, Ontario Was a Racist Asshole to Me.”9 Western’s President, Alan Shepard, constituted an Anti-Racist Working Group in January 2020, responding to complaints about racism on campus.

Racism in London has a long history, and not just in its less brazen forms. The underground railroad had two tracks. The better-known line brought fugitive slaves, whose journeys to places like London were early chronicled in Benjamin Drew’s The Narratives of Fugitive Slaves in Canada (1856). The other, less celebrated system transported Klansmen north after the defeat of the South in the Civil War, these unrepentant Confederates (sometimes under indictment in the United States) being well received in the Forest City, their experiences outlined in a recent popular history.10 London gained notoriety in the 1920s for Klan cross-burnings, and in 1980, Martin Weiche hosted Alexander McQuirter, head of the Canadian KKK, for an old-time cross-burning on his estate just outside of London. A dozen years later the Ontario Aryan Support Group did the same.

As a high school student radical, repelled by the confinements of dress codes, regimented hallways, and the hierarchies imposed by crew-cutted gym teachers, I was drawn to the radicalism of African American militants like the Black Panther Party. I also read Jerry Farber’s The Student As Nigger (1967) without any sense of outrage that later critics would marshal against its over-the-top comparison of very unlike oppressions. The pamphlet targeted what was wrong, even if it did so in ways that we would now see as inappropriate, or indeed, offensive. Racism demanded redress; so too did much else. I began to look for answers.

Some were provided by the Canadian Party of Labour (CPL). The Party, which adhered to a variant of Marxism programmatically propelled by the dizzying dialectics of Albania’s Enver Hoxha (there wasn’t much on far left offer in the London, Ontario, of the late 1960s!), played a role in recruiting me to the politics of anti-capitalism, drawing me into study groups and its conception of a Worker-Student Alliance. Its leading figures in London, whom I admired greatly for their bravery in supporting striking workers on picket lines and for their intellectual smarts, were Bob and Ruth Baldwin. Fresh from their days as activists in the Canadian Union of Students (CUS), the Baldwins were a daunting duo. They combined a Maoist-inflected streak of puritanical disdain for the youth culture’s promiscuity and drug use, along with a clarity of political purpose and what I regarded as deep learning in the classical texts of Marxism.

I wasn’t so much against sexual promiscuity and drug use at the time, as I was wondering what I had been missing. I did argue with the Baldwins, especially around feminist issues, which they tended to dismiss as “bourgeois.” I was a bit taken aback at the disdain they exhibited for women’s right to choose, their stand on abortion being one of decided opposition. More children for the struggle! When I put forward standard arguments about “every child a wanted child,” ‘Baldy’, as Bob was known, didn’t miss a beat with a quick retort. “We have members of the Party who are orphans,” he proclaimed emphatically, “and they have turned out just fine.” Enough said!

Bob and Ruth later left CPL, harbouring no residual fondness for their time in the Party. Bob, a brilliant economist, ended up as Director of the Social and Economic Policy Department at the Canadian Labour Congress, where he did exemplary work, especially as an expert on pensions. But what mattered most to me at the time was that the Baldwins, and the CPL that they led, were for the Revolution.

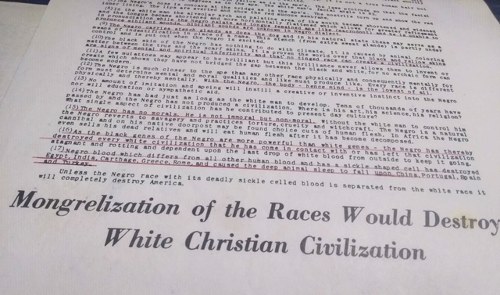

In either the fall of 1968 or the winter-spring of 1969, before entering university, I hitch-hiked from my parent’s suburban home to Western’s Althouse College auditorium. A Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan was on stage, spewing the venomous racism of his cause. I think the event was televised by a national outlet. I still have a leaflet distributed to those in attendance, headed by the absurd claim, “Scientists Say Negro Still in Ape Stage – Races Positively Not Equal,” closing with the obscene assertion, “Mongrelization of the Races Would Destroy White Christian Civilization.” I wanted to march to the mike in the Q & A period, a 17-year old high school kid determined to strike a blow against this repugnant filth, but cannot remember if I ever made it there, or if I did, what I said. It being a school night, I might have had to get home for bedtime.

In either the fall of 1968 or the winter-spring of 1969, before entering university, I hitch-hiked from my parent’s suburban home to Western’s Althouse College auditorium. A Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan was on stage, spewing the venomous racism of his cause. I think the event was televised by a national outlet. I still have a leaflet distributed to those in attendance, headed by the absurd claim, “Scientists Say Negro Still in Ape Stage – Races Positively Not Equal,” closing with the obscene assertion, “Mongrelization of the Races Would Destroy White Christian Civilization.” I wanted to march to the mike in the Q & A period, a 17-year old high school kid determined to strike a blow against this repugnant filth, but cannot remember if I ever made it there, or if I did, what I said. It being a school night, I might have had to get home for bedtime.

Western, Hilborn, and Anti-Racist Politics

Later that year, I enrolled in my first year of undergraduate classes at the University of Western Ontario. I would spend a brief two years there, broken apart by a year spent in New York City’s New Left and another year working as a waiter in a famed London Supper Club, the Iroquois Casino. My first year as a university student was at UWO-affiliated Huron College in 1969-1970. After a hiatus of demonstrations, picket lines, and classes at the movement school, New York’s Alternate U., and further time hustling lounge drinks, I returned to finish up a 3-year BA by taking summer courses and a packed final year at Western in 1972-1973.

My course work was concentrated in Russian, American, and Vietnamese history, although I spent as much time hanging around a few figures in the Sociology Department. I remember Hilborn as a controversial sort, an odd presence on campus, always dressed in a rumpled dark suit, white shirt, and tie, a guy who walked to and from his Department office and home to save bus fare, his briefcase swinging by his side. I have an image of him unwrapping his brown-bag lunches, eating at his desk in his corner office. Pennies saved were obviously dollars earned, as Hilborn’s worth at the end of his life confirmed. Known in London as a defender of South African apartheid who saw capitalist advancement of the privileged white minority as the salvation of the black masses, deploring the “terrorism” of those battling a racist political order with violent direct action, Hilborn offended left students with his op-ed pieces in the London Free Press. He was denounced as a racist.

In my last year at Western, I attempted to enrol in one of Hilborn’s classes. Because of my truncated undergraduate experience, I lacked the prerequisites that would have given me unconditional entry into specific upper level courses. A number of professors were willing to waive such restrictions for students who petitioned them personally, and showed a level of perseverance and interest in the material to be studied. Western’s announcement of the Hilborn legacy places an accent on his love of history and UWO’s students, but I didn’t really feel the love in my personal dealings with Hilborn. To be sure, my purpose in trying to get into his class was to challenge him and his ideas, and he may have sensed this. In any case, I was refused admission. My meeting with Hilborn was certainly uncomfortable, and I had trouble figuring out whether his motivation in squashing my attempt to take his class was entirely rulebound and mechanical, or if there were, indeed, political issues at stake in which he had me pegged as a problem best avoided. At his best, I found Hilborn just plain uncomfortable among people.

The Canadian Party of Labour (CPL) and other left-wing students formed a UWO Committee to Fight Racism, demanding that Hilborn be fired. It was a small bunch. Activists that led the way, to the best of my undoubtedly faulty memory, were Dave Hanna and Laura Hollingsworth, the latter a graduate student in the Sociology Department. If this was a motley crew, with some PhD candidates in the hard sciences rubbing shoulders with humanities undergraduates, the History Department had virtually no student involvement in what passed for Western’s miniscule left-wing milieu. All political campaigns of this kind at Western marched into a stiff headwind of political apathy. Students, in my judgement, were far more interested in the Mustangs (the UWO football team) than in mobilization. There was a lot more liking of Dr. Strangelove than there was affinity for flower power, let alone much evidence of a love of Lenin. In this sense, it is not surprising that Hilborn’s classes of the 1960s and 1970s (and perhaps beyond) were popular: he confirmed the prejudices of a student body that seemed largely captive of the hegemonic Cold War ideology of the times.

I cannot remember, through the fog of fifty years, what role I played in the Committee to Fight Racism, although I seem to recall being at meetings. I may be confusing these with gatherings of another left body at Western, organized to protest the Vietnam War, and named the Anti-Imperialist Front. It was founded by Bill Cecil-Smith, the son of a Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion leader, the Canadian contingent that fought against Franco in the Spanish Civil War.

At one of these gatherings, I denounced faculty involvement in student protest activity, rising from the floor righteously to tell two well-meaning and decent Sociology professors – Jim Rinehart and James Geschwender – that we didn’t need their guidance or advice on how to conduct our struggles. My good friend and long-time supporter, the wry, cigar-smoking teacher of “social stratification” and later author of The Tyranny of Work (1975), Jim Rinehart, never let me forget that performance.

Hilborn became the target of student protests, deservedly so I thought at the time, and I continue to believe today. I was part of calling for his dismissal. But years later, I have come to a slightly different position.

This, to me, is a central issue raised by criticisms of scholarships at Western bearing Hilborn’s name. The suggestion is that when university departments dispense money with a name commemorated, writing the history of that name is how best to address the wrongs that may be associated with it. I don’t necessarily disagree, yet I doubt this call to write the past, however laudatory, addresses everything that needs to be thought through. To begin with, understandings of what constitutes addressing the history of Hilborn differ markedly, and this will always be the case. How history is conceptualized and contextualized, researched, and written, will always be contested terrain. This conflictual reality means that coming to grips with what happened in that history is not only about facts, but also about considerations of what was done, what could have been done, and even what should have been done, along with what this all might tell us about the present. My thoughts, retrospectively, turn on what some of us did and tried to achieve in our opposition to Hilborn.

Calling for Hilborn’s dismissal, within an institution like Western, was probably wrong-headed. I say this as someone highly concerned about freedom of speech/academic freedom issues some critics claim have been collapsed wrongly into one another. It is unclear to me if this distinction would be embraced by all, including staunch defenders of freedom of speech such as Noam Chomsky. And if, like me, you have actually faced the unpleasantry of someone writing to the Principal of your university, and to your Member of Parliament, demanding you be fired for your views, you might take academic freedom to be something other than what people like Ken Hilborn used it to promote. Critics can well claim, with some justification, that right-wingers and racists use academic freedom “as a cover for spewing hate.” But this does not mean that academic freedom/freedom of speech can be reduced to only this.

I agree entirely that academic freedom is, indeed, premised on scholarly responsibility, a principle Hilborn would, at least abstractly, have endorsed as well, if his leaflet-like writing for SAFS is to be believed. But his thought was not, in my brief foray into uncovering some of his obscure writing, all that clear. For instance, what is one to make of a statement delivered at an SAFS symposium in 2004 on “The Limits of Academic Freedom”? Hilborn declared that, “though denial of the Holocaust would have to be treated as an issue of fact, approval of the Holocaust (or of other policies of mass murder) is an opinion that places a person holding it outside the boundaries of legitimate controversy – and therefore outside of the shield of academic freedom.” I take this to mean that denying the Holocaust is fine (as long as some ‘evidence’ – however weak or compromised it may be – can be marshalled to sustain such a claim), but advocating another one, not so good.

To the extent that Hilborn’s offensive views that brought the Committee to Fight Racism into being were posed in an op-ed piece in a local newspaper, it would have been difficult to raise questions about his scholarship, and its responsible use of evidence and any other “issue of fact.” A future student protest at UWO was able to raise such questions in the late 1980s and 1990s around the racist, sociobiological publications (and their funding) of Phillipe Rushton. Rushton was rightly, in my view, condemned, not only for his interpretation of racialized bases of intelligence, but also, for taking his research money from sources clearly interested in findings that confirmed their repugnant views.

In Hilborn’s case, there just was nothing in the way of scholarly production to go after, only opinion expressed in non-academic venues. In the very early 1970s, questions of tenure and its rootedness in the vetting of academic publications were simply not raised forthrightly and rigorously, and probing into academic qualifications of a tenured professor was, at least in my recollection, seldom done with much scrutiny. It could now be pressed far more strenuously and, perhaps, as the opposition to Rushton illustrates, successfully.

If assessing the validity of the qualifications of those hired within universities is one way of resisting instructors who use their academic positions as a platform to espouse repugnant views, it need not necessarily be accompanied by calls for such institutions and the states that fund them to fire professors. An orientation that protests, and strikes its blows directly against ideas that offend, can well leave in abeyance the issue of dismissal. This can be effective as a way of discrediting certain ideas and those who espouse them. Such an approach validates struggles, but does not put the outcome of employment in an institution rife with offense as the sole end, or call on authorities whose power is already immense to fire people with unpopular views. If those protesting, in terms of numbers and of reasoned argument, are so strong that the case being made cannot be ignored, then a victory of sorts has been won. Focussing on the substance of protest, rather than an outcome such as dismissal, shifts the terms of trade in such controversies so that the issues, rather than the individuals taking stands on them, are what matters. If struggles succeed on this basis, then the final onus of responsibility will be borne by those who have the power to limit the teaching or terminate for cause the appointment of an instructor.

To be effective, such a challenge would necessarily have to involve a sustained mobilization of students, faculty, and staff at the university where a professor putting forward offensive views was teaching. The building of such a campaign could protest in various ways, as the mobilizations against Rushton revealed to some extent, I expect. Yet it is more than apparent that the climate of the times, and the diversity of the student body at Western, was very different in 1970 than it was at the end of the 1980s. Or, today.

Different historical contexts and political environments aside, how can one refuse to countenance extreme right-wing, racist, misogynist, and homophobic views within universities? Even the list suggests how times have changed, with some reactionary thought, such as anti-communism and anti-Marxism, now being more acceptably mainstream. Whatever the circumstances, there are ways of combatting what is unacceptable that do not depend on demands for dismissal. Enrolling in classes to protest the views of instructors, including, if the will was there, mobilizing mass walkouts, is one ‘inside’ option. So, too, is an ‘outside’ approach: boycotts of classes taught by faculty who put forward racist or other repugnant ideas, sending a message of refusal, as well as collectively animating students and others in ways that could galvanize activism and widen struggles. Such protests could end in various ways, up to and including dismissal, but calling for the firing of professors in such situations is a dangerous strategic move.

The obvious problem is that if right-wing professors are going to be sacked for their views, we can rest assured that left-wing professors will be fired far more frequently. If it is just to get rid of Professor A for being a racist, it will not be long before someone gets the bright idea that it is equally just to dump Professor B for being a socialist feminist or Fidelista Marxist. Rationalizing the firing of professors of the right will only be met with counters, demanding the dismissal of professors of the left. All of this, of course, assumes that the ideas professors put forward outside the classroom are all that is being considered, which is probably quite difficult to ascertain. It leaves in abeyance treatment of students in the classroom. Discriminatory practices, whether of the right or the left, are always subject to disciplinary action, if they are confirmed to have happened.

History can be a useful guide, for academic life over the course of the last 150 years has seen far more opposition and victimization of left-wingers than uprisings against the right. As much as there are currently many admirably protesting the presence of right-wing views and the history of racism in higher education, conservatives in Canadian universities are also becoming more vocal in their irrational, uninformed attacks on what they indiscriminatingly consider the dominance, à la Jordan Peterson, of an all-powerful ‘Marxist, postmodernist left.’ That such a left does not really exist is a nuance well beyond Peterson’s capacity to grasp differentiations on a complex political spectrum. Lindsay Shepherd concocted her five minutes of fame on the international stage of academic freedom by parlaying how, as a teaching assistant, her methods of inquiry and instruction were infringed upon by intolerant left-leaning professors. What got lost in the stampede of assault on these professors, who did not handle a bad situation all that well, is that Shepherd was, in fact, a teaching assistant, which by definition means that she was paid to assist the instructor in the course. My own preference would be to extend such assistants a great deal of latitude, but those of us on the left who have experienced right-wing TAs who thought it was their job to “correct” our instruction, in effect sabotaging a course we were responsible for, will empathize with the problems presented by tutorial leaders who consider themselves primarily critics rather than assistants. So willing were so many, especially in the mainstream media, to condemn ostensible leftists gone wild, that this elementary point got lost in the barrage of denunciation.

As outlandish as it may seem to some, I do not consider universities today to be dominated by the left. It all depends, of course, on what is considered left. The times have changed from the 1950s, to be sure, when a liberal-conservative mainstream was clearly hegemonic, and a marginal social democratic contingent was barely allowed a presence. Marxists, forget about it. Today, there are a few Marxists here and there, in some fields, to be sure, with a select number even exercising considerable influence. The dominant politics within academia is now certainly far more progressive and liberal than it was decades ago, with cranky reactionaries more marginalized. There are just not that many equivalents of Ken Hilborn employed in Canadian universities today. The entire culture is undeniably more sensitive to racism and the politics of identity than it once was, and this registers in academic life in all kinds of ways.

How left is all of this? It is a question that can be asked, and answered, in a variety of ways. But a resolute defense of left wingers is not really integral to the academic culture of the moment, and never has been. And I do not think it contradictory to state that while arch conservatives are an endangered species in most humanities and social sciences departments outside Economics today, that are staging a comeback: emboldened by the political shift to the right in the culture of the current moment, voices of conservatism in the university have grown more confident of late and platforms like twitter licence statements about the left that are shockingly irresponsible. With most faculty aligning with what they deem ‘progressive’ views, it is also the case that there is actually now less tolerance of the far left than there was a few decades ago. My impression is that this is reflected not only in hirings, but in all kinds of negative commentary, much of it coming from established scholars who are far more prone to indiscriminately target ‘Marxists’ than would have been acceptable in the relatively recent past. Not all of this comes from the right.

To establish the point that the left calls for the dismissal of professors espousing offensive views at its peril, it is only necessary to look at the origins and evolution of the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). First established in 1938 to investigate the role of fascists and communists in the United States, HUAC spent a metaphorical few minutes ferreting out a couple of Nazis from the woodwork they had ensconced themselves in, and then moved on to spend decades persecuting thousands of supposed (and some real) communists. Many of these targets of the witch-hunt taught in public and secondary schools, colleges, and universities. HUAC also championed the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II, and declined a 1946 prod to investigate the Ku Klux Klan, one Dixiecrat proclaiming, “After all, the KKK is an old American institution.” Indeed, it was. The Klan was finally looked into by HUAC in 1965. But this came after many leftist lives had been ruined; the Cold War waning, the state was turning its repressive apparatus, full-bore, against African American militants like the Black Panther Party. Some of these Panthers were murdered by state agents, while others were subject to the sometimes lethal machinations of provocateurs.

Universities claim to be pluralist institutions, and the best that the left can do is insist that they live up to this inclusiveness. Protests against professors who espouse racist and other repugnant views should be mounted and can be successful in a variety of ways. Making ideologues uncomfortable is part of what any mobilization of students and others should be doing. But this means organizing, educating, and building mass movements of resistance so that hundreds, not handfuls, of students recognize all manner of offensive ideological postures. It was exceedingly difficult to do this at Western in the early 1970s. Calling into question research that is skewed by prejudice and discriminatory thought or bought and paid for by organizations committed to this bigotry, placing these ideologues on the spit of a rigorous scholarly roasting, is both easier to do today as well as being less likely to happen, since targets like Hilborn are not commonplace.

The danger, I suspect, is not that some mythical academic left will run roughshod over the far right, undermining the academic freedom of a reactionary minority. The attack is more likely to be on the few leftists that do exist within university departments, perhaps extending indiscriminately to well-meaning progressives, whom the right will paint into some Marxist, ultra-left corner. To the extent that such people allow themselves to be presented as against academic freedom and the right to express unpopular views, they will almost certainly feed an anti-left backlash, one that has been quietly building up a head of steam over the last difficult decades, and one that has long targeted left scholarship as ‘ideological’ when liberal, mainstream, and conservative research and writing is presented as objective.

Those who stand on leftist ground politically will always be required to publish more, and to do so in ways that establish the undisputed excellence of their research and writing. A far-left equivalent of Hilborn would have been hard to find in a Canadian university in the 1960s. He or she simply would never have been hired.

In a society in which leftists are anything but hegemonic, often scapegoated as pariahs, it is unfair that the standards they are held to are going to be higher than those demanded of the mainstream. But that is the way it is. Because of this, leftists must draw some lines of distinction between scholarship and politics. If they acknowledge that these are not entirely different entities, and that a 1950s ‘value-free’ social science is an impossibility, there should be some separations made. Political commitments (which all in the university have to be allowed to have), teaching (which must be something more than merely a platform for putting forward one’s views), and scholarship (which, while it will never be innocent of values and political positions, will adhere to the rigours of research) are all related, at the same time as they are, in some important ways, distinct from one another.

When and if the history of Kenneth Hilborn and the History Department at the University of Western Ontario gets written, I expect complications will abound. I wouldn’t venture into a deep discussion of what the Western History Department should do about the Kenneth Hilborn scholarships, although I have offered some quite minor constructive suggestions above. I don’t know enough about what was involved in the legacy, and the Department has taken its stand. The money is not going back. Certainly, all of us who have been funded from various sources have taken material support that comes weighted down with burdens and offenses structured into the historical and contemporary associations of the largesse that sustained our research.

What I would suggest is that this issue should have been addressed by Western as a university with more care and consideration, before the money became an issue to be allocated to and discussed within the History Department. A legacy of $1,000,000 was almost certainly vetted by some kind of Advancement and Donations Department. These kinds of centralized clearing houses don’t much like mere and mortal academic units sticking their noses into the large financial business of universities. They want the cash, and they want it filtered through them.

It was the job of the people managing this from the outset to know that the Hilborn gift came with some baggage. A sum of the magnitude of the Hilborn legacy could not simply have been dropped in a mailbox upon Hilborn’s death. What happened when Hilborn proposed his bequest? Were there discussions of the necessity of naming all of the scholarships in the History Department after Hilborn? Was the money tied to such naming? Were there negotiations around this? Does Western have clearly worked out positions on people ‘buying’ a named posterity? This is generally the prerogative of the truly rich and is seldom questioned in our culture of acquisitive individualism. Hilborn managed to amass sizeable personal savings, but he did not have an Ivey Foundation to filter them to various institutions. Was there any appreciation that Hilborn’s politics needed to be factored into Western taking the money? Does Western as a university garner financial benefit from Hilborn’s legacy, through interest accruing on the principal, or through servicing fees, or is the entirety of the endowment benefiting the two departments where scholarships have been set up?

Questioning the Unacceptable

I am well aware that my entire missive is more about questions than answers. I don’t think that is necessarily a bad thing. A lot begins, and should so start, with questions.

My trip down memory lane and the case of Kenneth Hilborn has raised for me the recognition that fighting the right within universities has never been, and is not now, easy. Academic freedom and freedom of expression are difficult negotiations for all of us, but they are of sufficient import that they demand careful consideration. That the right needs to be combatted, and that its validation can come in many different and nuanced ways, is as apparent today as it was in 1970. That this fight carries with it a set of responsibilities and considerations, in which history itself can ever only be a part, however necessary, of a solution, seems equally evident. The politics of refusing to accept the unacceptable is always going to pose as many challenges as it itself raises. •

I would like to thank Neville Thompson, who taught me in the first-year History course at Huron College in 1969-1970, and Francine McKenzie, current Chair of Western’s History Department, for discussing an earlier draft of this essay with me. They bear no responsibility for the positions taken.

Endnotes

- Asa McKercher, “University Donations and the Legitimization of Far-Right Views,” Active History, 12 September 2019; Will Langford, “Congress 2020 Interrupted: Racism, Academic Freedom, and the Far Right, 1970s-1990s,” Active History, 28 April 2020; Langford, “Congress 2020 Interrupted: Racism and Commemoration in Western University’s Department of History,” Active History, 5 May 2020; Francine Mckenzie, “Western’s History Department and the Hilborn Student Awards,” Active History, 7 May 2020.

- Fred Landon, “The Common Man in the Era of the Rebellion in Upper Canada,” in F.H. Armstrong, H.A. Stevenson, and J.D. Wilson, eds., Aspects of Nineteenth-Century Ontario: Essays Presented to James J. Talman (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1974), 154-170.

- Karolyn Smarz Frost et al., eds., Ontario’s African-Canadian Heritage: Collected Writings By Fred Landon, 1918-1967 (Toronto: Dundurn, 2009); Landon, “The Knights of Labor: Predecessors of the C.I.O.,” Quarterly Review of Commerce. 1 (Autumn 1937), pp. 133-139; Landon, “The Canadian Scene, 1880-1890,” Canadian Historical Association Annual Report (1942), pp. 5-18.

- Kenneth H. W. Hilborn, “Abuse of Academic Freedom: What Should Be Done?” Paper presented to Annual General Meeting, Society for Academic Freedom and Scholarship, May 2004.

- “UWO Prof Attacked as Racist,” The Ubyssey, 23 November 1971.

- Hilborn, “Abuse of Academic Freedom.”

- Kenneth H. W. Hilborn, “Taken By Surprise: The United States, Canada, and Anti-Missile Defence,” Consent: 32, December 2001.

- For a full discussion of any number of Canadian academic freedom cases see Michiel Horn, Academic Freedom in Canada: A History (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999).

- Eternity Martis, “London, Ontario was a Racist Asshole to Me,” Vice, 7 May 2015. Martis has extended this discussion, which raised considerable ire in London, in a recent book: They said this would be fun: Race, Campus Life, and Growing Up (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 2020).

- Ron W. Shaw, London Ontario’s Unrepentant Confederates, the Ku Klux Klan and a Rendition on Wellington Street (Ottawa: Global Heritage Press, 2018).