The Communist Movement at a Crossroads

Under the general editorship of John Riddell, the record of the Communist International (Comintern) under Lenin has been retrieved from history and made alive again for our time. The aim of this series of texts, starting in 1983, has been to present the record, documents and debates of the Comintern, in its own words. The series chronicles the development of this dynamic revolutionary undertaking and showing it as a vibrant and living movement embracing millions around the world.

Posted here is the introduction to The Communist Movement at a Crossroads: Plenums of the Communist International’s Executive Committee, 1922-1923. Edited by Mike Taber and translated by John Riddell, the book is published by the Historical Materialism Book Series, and is available from Haymarket Books. This latest volume is noteworthy in showing the Comintern taking up several questions of contemporary relevancy, among them the united front and fascism. For this reason, the book will be of special interest both to those studying the history of the world Communist movement and also to activists seeking to examine key strategic questions that remain on the agenda today.

Mike Taber’s Introduction presented below provides a summary not only of the book but of the issues raised within it and the Comintern’s evolution in the period under study. This essay originally published on the John Riddell – Marxist Essays and Commentary website.

On 1 January 1922, the Communist International (Comintern, 1919–1943) issued an appeal to “working men and women of all countries” calling for the creation of a workers’ united front to fight the ravages of capitalism. It stated:

“The Communist International calls … on all upstanding workers around the world to come together … as a family of working people who will respond to all the distress of our time by standing together against capital. Create a firm spirit of proletarian unity against which every attempt to divide proletarians will break down, no matter where it originates. Only if you proletarians come together in this way, in the workplace and the economy, will all parties based on the proletariat and seeking to win a hearing from it find that joining together in a common defensive struggle against capitalism is necessary.”1

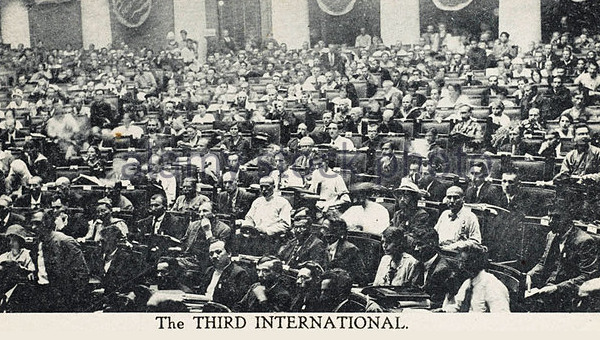

This appeal for united action also summoned the Comintern’s member parties to send representatives to a special conference: an ‘enlarged plenum’ of the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI). Such conferences – Grigorii Zinoviev would label them ‘small world congresses’ – thereafter became regular Comintern events.2

The Communist Movement at a Crossroads contains the proceedings and resolutions of the three enlarged plenums that took place while Lenin was still alive. For any study of the Communist International, these plenums are close in importance to the four Lenin-era world congresses that took place between 1919 and 1922.3 Many of the Comintern’s main decisions in those years were taken by these plenums, making important contributions to the Communist International’s political legacy.

This introduction aims to review each of these three conferences, putting them in context and highlighting their main discussions and decisions.

World Situation in 1922–23: Capitalist Contradictions

In the first three years following the end of World War I, the capitalist rulers of Europe faced a real threat of proletarian revolution, which was inspired by the Russian Revolution and driven by the explosion of class tensions that had been accumulating over the course of the war. The main efforts of the rulers in these years were geared to ensuring the very survival of their system. By late 1920, however, it had become clear that world capitalism had withstood the initial onslaught and was achieving a tenuous stabilization. Nevertheless, by early 1922 contradictions within the world imperialist system were sharpening.

Through the 1919 Treaty of Versailles and related treaties, the war’s victors had sought to impose on the vanquished powers a new world order: redrawing borders, creating new nation-states, and re-dividing the world into new spheres of influence. But rather than ensuring a stable and lasting order, the Versailles system had the opposite effect.

The most immediate cause of this instability was Germany’s inability to pay the massive war reparations imposed by the Versailles Treaty. Numerous financial conferences and meetings were held during these years to work out new payment plans. When none of these worked, the victorious powers resorted to outright theft. In early 1921, French troops were sent to occupy the Ruhr region – Germany’s main coal-producing district – in an attempt to seize this valuable resource. In January 1923, a larger invasion and occupation of the Ruhr was undertaken.

In leading governmental circles, the threat of renewed imperialist war was openly discussed, generating an arms race. In his report to the Third Enlarged Plenum on the world political situation, Karl Radek quoted a perceptive bourgeois observer: ‘It was said by idealists, that this war [World War I] would end all wars; but it seems as though it had merely sown the seeds of further wars, giving rise to a ‘mad race in armaments which they are still pursuing’.4

During these years, capitalist governments held various conferences in a vain effort to reconcile their competing interests – in Genoa, Lausanne, Paris, The Hague, Washington, and other cities. All of these conferences merely served to demonstrate the irreconcilability of rival interests, as well as the vulnerabilities of the imperialist world order as a whole.

Soviet Russia

The Russian Soviet republic was a major factor in this picture.

During the Soviet regime’s first three years after its establishment in October 1917, no capitalist power sought significant diplomatic or economic relations with it, banking instead on the overthrow of Soviet power. During the Russian Civil War, the leading capitalist states armed and supported the Russian counterrevolutionary armies. Not satisfied with that, over a dozen of these states – including Britain, France, Japan, and the United States – actively intervened by sending troops.

However, by the end of 1920, the Red Army had beaten back the counterrevolutionary forces militarily, leading some capitalist governments to change their approach. Thinking they could utilize Soviet Russia to improve their positions vis-à-vis rivals, some powers began seeking economic and diplomatic relations with Soviet Russia, hoping that the Soviets would in return abandon their revolutionary perspectives.

In 1922, Germany and Soviet Russia signed the Rapallo Treaty, normalizing relations between the two countries. Britain, too, had signed the Anglo-Soviet Trade Agreement the previous year, as a way of counterbalancing its rivalry with France. For the first time, Soviet Russia even started to receive invitations to participate in governmental conferences.

As a general principle, Soviet Russia expressed a willingness to negotiate and enter into relations with all capitalist governments. But the Bolshevik leadership rejected out of hand calls to abandon its support for world proletarian revolution, as well as for the struggles of the colonial peoples against imperialist subjugation.

As these contradictions within the capitalist world deepened, the class struggle was intensifying in a number of European countries, above all in Germany. Alongside this picture, an upheaval in the colonial world was also taking place.

Colonial World in Revolt

The October 1917 revolution in Russia gave a major boost to the developing movement for freedom and national liberation in the colonial and semi-colonial countries of Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Revolutionary explosions were felt in every corner of the world: China, Korea, the Dutch East Indies, British India, predominantly Islamic countries of southwestern Asia and north Africa, as well as Latin American countries such as Mexico and Cuba.

Not only did the Communist International pledge its full support to the struggle of the colonial peoples, but it also gave major attention to building Communist parties in these countries. For the first time, a genuine worldwide revolutionary movement began to take shape – not limited to Europe and North America, as had been the case with the First and Second Internationals.

To advance this perspective, the Comintern took important initiatives. It organized the 1920 Baku Congress of the Peoples of the East and the 1922 Congress of the Toilers of the Far East.5 It also organized a Central Asian Bureau and a Far Eastern Secretariat as more permanent bodies.

In addition to support from the Communist International, the movement for national liberation of the colonial and semi-colonial world received the full support of Soviet Russia itself. During the period covered by the present volume, the Soviet republic began establishing ties of support and collaboration with independent states such as Turkey and China, countries that were engaged in struggles to break free from imperialist control.

The Communist International’s 1921 Turn

The revolutionary wave that swept Europe following the end of the First World War was so powerful that in two places – Hungary and Bavaria – Communist parties were swept into power without having a clear understanding of what was happening or what to do next. In other countries (Italy, Germany), workers were close to victory.

During these years, the Third, Communist International was formed and held its first two congresses. Based on the experiences of the October 1917 revolution in Russia, the Bolshevik leadership aimed to transform the Communist movement – composed of disparate revolutionary forces – into centralized and politically competent parties. To make this possible, the first two congresses focused on setting down the programme and basic perspectives of the new world movement.

The young and inexperienced Communist forces, however, were unable to take advantage of the revolutionary wave in Europe. Between 1918 and 1920, promising revolutionary movements went down to defeat, one after another.

By late 1920, it had become clear that the revolutionary wave was receding. That fact was recognised by the Comintern’s Third Congress in June -July 1921. In doing so, the congress affirmed the goal of winning a working-class majority, registered in its watchword of ‘To the masses!’

The world situation at the time was summed up by Leon Trotsky in his report to the Third Congress:

“[T]he situation has become more complicated, but it remains favourable from a revolutionary point of view. … But the revolution is not so obedient and tame that it can be led around on a leash, as we once thought. It has its ups and downs, its crises and its booms, determined by objective conditions but also by internal stratification in working-class attitudes.”6

In line with this analysis, the congress stressed the importance of strategy and manoeuvre, adopting the general perspective of the workers’ united front.

The Communist International’s turn of 1921 posed a number of strategic and tactical questions that came up for discussion and debate at the three enlarged ECCI plenums that met in Moscow in 1922 and 1923.

A Crossroads

The three enlarged plenums recorded in this volume show the world Communist movement at a crossroads:

– While the Comintern was formed in 1919 during a period of revolutionary advance in Europe, the Communist movement by 1922-3 had entered a new conjuncture. It was a period that required a mature strategic outlook and the ability to manoeuvre in order to advance the Comintern’s perspective of world proletarian revolution. In this context, the fight for a working-class united front moved to the centre of its strategic orientation.

– While confronting growing opportunities for building Communist parties, by 1923 the international Communist movement stood on the verge of a struggle over whether it would remain a revolutionary working-class movement, or instead become subordinated to the narrow interests of a bureaucratic caste in the Soviet Union under Stalin. Under the thumb of an ever-more-powerful Comintern apparatus in Moscow, by the 1930s Communist parties around the world would be fully transformed from independent-minded revolutionary vanguards into monolithic agencies promoting the shifting policies of the Soviet bureaucracy.

To fully appreciate this crossroads, a review of the proceedings and resolutions of the first three enlarged ECCI plenums is necessary.

First Enlarged Plenum (February–March 1922)

Adoption of United-Front Policy

While the idea of a workers’ united front has antecedents in the history of the socialist movement going back to the First International led by Marx and Engels and to the Bolshevik Party of Russia, the immediate roots of the Comintern’s united-front policy of 1921-22 can be found in Germany.

The German workers’ movement at the time was sharply divided between three main parties: the reformist Social-Democratic Party (SPD), the centrist Independent Social-Democratic Party (USPD), and the Communist Party (KPD).

In the face of an escalating capitalist offensive – with attacks on wages and working conditions, growing unemployment, and the beginnings of the hyperinflation crisis – by late 1920 powerful sentiment had developed within the ranks of the German working class in favour of a united fight by all currents within it.

Recognizing this sentiment, in early January 1921 the German Communist Party issued what became known as the Open Letter. This was a document addressed to all major German workers’ organizations calling for united action to defend the life-and-death interests of the German proletariat. While the Open Letter stirred initial opposition within the world Communist movement – including within the Russian CP leadership – its basic approach received Lenin’s strong support.7

The Comintern’s Third Congress endorsed the German Open Letter, calling for the same approach to be adopted by Communist parties internationally:

“… Communist parties are obliged to attempt, by mustering their strength in the trade unions and increasing their pressure on other parties based on the working masses, to enable the proletariat’s struggle for its immediate interests to unfold on a unified basis. If the non-Communist parties are forced to join the struggle, the Communists have the task of preparing the working masses from the start for the possibility of betrayal by these parties in a subsequent stage of struggle. Communists should seek to intensify the conflict and drive it forward. The VKPD’s Open Letter can serve as a model of a starting point for campaigns.”8

That perspective was codified five months later, when the Comintern Executive Committee adopted a set of theses formulating the new policy. The perspective of the December 1921 theses was premised on the working class internationally being forced onto the defensive, but with an increasing willingness to fight back.

“[U]nder the impact of the mounting capitalist attack, a spontaneous striving for unity has awakened among the workers, which literally cannot be restrained. It is accompanied by the gradual growth of confidence among the broad working masses in the Communists. …

“But at the same time, they have not yet given up their belief in the reformists. Significant layers still support the parties of the Second and Amsterdam Internationals. These working masses do not formulate their plans and strivings all that precisely, but by and large, their new mood can be traced to a desire to establish a united front, attempting to bring the parties and organizations of the Second and Amsterdam Internationals into struggle together with the Communists against the capitalist attacks.”

The theses also stressed that Communist parties must ‘maintain absolute autonomy and complete independence’ when engaged in united-front activity. ‘While supporting the slogan of the greatest possible unity of all workers’ organizations in every practical action against the united capitalists,’ the theses declared, ‘the Communists must not abstain from putting forward their views, which are the only consistent expression of defence of the interests of the working class as a whole.’

The new policy was not without possible dangers, however:

“Not every Communist Party is sufficiently developed and consolidated. They have not all broken completely with centrist and semi-centrist ideology. There are instances where it may be possible to go too far, tendencies that would genuinely mean the dissolution of Communist parties and groups into a formless united bloc.”9

Not everyone in the Communist movement supported the new approach, however. The policy evoked strong objections from the leaderships of the Communist parties of France, Italy, and Spain, whose representatives expressed their disagreements at the First Enlarged Plenum two months later.

Plenum Debate on United Front

In his report on the united front to the plenum, Zinoviev went over the motivations for the new policy. During the revolutionary wave of 1918–20, he explained, prospects seemed to indicate that workers were on the road to rapidly taking power and rejecting their Social-Democratic misleaders. Driving through a split with them quickly, Zinoviev asserted, was the central task for Communist forces during these years.

In the wake of the defeat of the postwar revolutionary wave, however, ‘after four years of hunger and breakdown, the working class has need for a respite.’ But the capitalists, in their quest for profits, will not give that to them.

“The working masses that previously were striving for a respite now begin to comprehend that there is no way forward without struggle. … [But] the workers seek unity; they want to struggle together against the bourgeoisie. If Communists do not take this mood into account, they will become sectarians.”10

It was this mood within the working class that gave rise to the united-front policy, which Zinoviev described as a “tactical manoeuvre.”11

Zinoviev’s report was followed by counter-reports given by Daniel Renoult of France and by Riccardo Roberto and Umberto Terracini of Italy. In his counter-report, Renoult objected to “concluding partial and temporary agreements with the discredited leaders of Social Democracy or the reformist syndicalists.”

Terracini’s counter-report went even further:

“Should we, in order to win the masses, abandon precisely the principles that have enabled us to acquire strength? In our view, the methods proposed to us by the Executive Committee may indeed enable us to win the masses, but we will then no longer be Communist parties, but rather, the spitting image of Social-Democratic parties.”12

Terracini also drew a distinction between trade unions and political parties. A united front, he argued, was suitable for unions but not parties. “Every party must set down a number of issues suitable for engaging all workers, issues relating to the economic situation and to political and military reaction. This proposal is to be directed solely to the national trade unions and not to the political parties.”

Roberto echoed this view: “We must loudly declare that every Communist Party has the duty to establish a united front not with the leaders but with the masses organized in trade unions, who will carry the Social Democrats and the leaders along with them and expose them.”

During the debate, delegates spoke for and against the united-front policy. In his remarks, Trotsky responded to the objections raised against the policy:

“We do not know when the moment for the conquest of power will come. Perhaps in six months, perhaps in six years. I ask Comrades Terracini and Renoult: Is the proletariat’s struggle supposed to stand still until the moment when the Communist Party will be in a position to take power? No, the struggle goes forward. Workers outside our party do not understand why we split from the Socialists. They think, ‘These groups or sects should give us an opportunity to struggle for our daily necessities.’ We cannot simply tell them, ‘We split in order to prepare for your great day after tomorrow.’

“But the Communist Party comes to them and says, ‘Friends, the Communists, syndicalists, reformists, and revolutionary syndicalists all have their separate organizations, but we Communists are proposing an immediate action for your daily bread.’ That is fully in step with the psychology of the masses.”13

Following the debate, which lasted for seven sessions, the united-front perspective was adopted by majority vote, over the opposition of the Italian, French, and Spanish delegations. Those opposing the decision nevertheless pledged to carry out the new policy.

Discussion on Soviet Russia

Another noteworthy feature of the First Enlarged ECCI Plenum was its attention to developments in Soviet Russia.

It was considered fully appropriate for Comintern congresses and leadership meetings to discuss, debate, and issue judgments on important issues that arose in the Soviet republic. This norm – standard procedure in the early Comintern – contrasted sharply with the Stalin-led Comintern of the 1930s, in which the policies of the Soviet CP were viewed as sacrosanct.

The First Enlarged Plenum examined the following:

– A set of theses presented by Grigorii Y. Sokolnikov on the implementation of the New Economic Policy.14 The NEP comprised a series of measures introduced in Soviet Russia in March 1921 and subsequently, aiming to restore economic relations between city and countryside. The NEP permitted peasants to freely market their grain, restored freedom of commerce, provided scope for small-scale capitalist enterprises, and subjected state-owned enterprises and administration to budgetary controls.

– An appeal from the Workers’ Opposition. This was a group within the Russian CP, formed in 1920, that called for trade-union control of industrial production and greater autonomy for CP fractions in the unions. Its appeal to the plenum raised criticisms related to the introduction of the NEP and growing bureaucratization within the Communist Party. The Russian Communist Party Central Committee issued a written response to this appeal.15 A commission was assigned to investigate, which prepared a resolution that was approved by the plenum.

– A report by Willi Müinzenberg on the international relief campaign for victims of the famine in Russia, which killed several million people in 1921–22.16 This campaign was undertaken as a broad workers’ movement reaching out to all political tendencies. As Münzenberg reported, it was an “attempt to unify all workers in the campaign, whatever their party or trade-union affiliation,” an “attempt to realise the united front in practice.”

Other Topics Discussed

Other topics discussed at the First Enlarged Plenum included: – The trade-union question. The plenum heard reports by S.A. Lozovsky and Heinrich Brandler on the progress of the Red International of Labour Unions (RILU, or Profintern, based on its Russian initials) and on Communists’ tasks in the unions.

The RILU had been formed the previous year at a congress in Moscow as a revolutionary class-struggle trade-union pole, consisting of both Communists and revolutionary syndicalists. It was openly counterposed to the Social- Democratic-led International Federation of Trade Unions, also known as the Amsterdam International. Despite its opposition to the right-wing Amsterdam leadership, the Profintern’s perspective was not to split the unions. Its goal was, instead, to transform the existing unions into instruments of revolutionary struggle. Wherever unions remained affiliated to Amsterdam, the RILU sought to act as loyal and disciplined minorities within them. The Amsterdam leaders, however, did not share this interest in trade-union unity. When the social-democratic union heads felt their control to be threatened by Communists and revolutionary syndicalists, they would often simply expel the offending unions and unionists.17

The RILU had been formed the previous year at a congress in Moscow as a revolutionary class-struggle trade-union pole, consisting of both Communists and revolutionary syndicalists. It was openly counterposed to the Social- Democratic-led International Federation of Trade Unions, also known as the Amsterdam International. Despite its opposition to the right-wing Amsterdam leadership, the Profintern’s perspective was not to split the unions. Its goal was, instead, to transform the existing unions into instruments of revolutionary struggle. Wherever unions remained affiliated to Amsterdam, the RILU sought to act as loyal and disciplined minorities within them. The Amsterdam leaders, however, did not share this interest in trade-union unity. When the social-democratic union heads felt their control to be threatened by Communists and revolutionary syndicalists, they would often simply expel the offending unions and unionists.17

– Youth. The plenum heard a report from a leader of the Communist Youth International that focused on the situation of young workers and outlined a programme of demands for Communist parties to use in their work among them.18

– The war danger. The plenum heard a report by Clara Zetkin on the renewed danger of imperialist war. “After the World War ended, the cry went up: ‘Never again war’,” Zetkin told the meeting, “But today we face new dangers of war. The world is loaded with explosive material that at any moment could set off new and even worse wars.” United-front action was required to combat this danger, she pointed out, ultimately posing the need for revolutionary change:

“Against the threat of world war we must establish a solid united front of the proletariat for the struggle against war and imperialism. The struggle against the dangers of war and armaments must be a step forward toward winning political power of the proletariat. Only the overthrow of capitalism can lead humankind to world peace.”19

Second Enlarged Plenum, June 1922

Conference of the Three Internationals

At the First Enlarged Plenum, there had been discussion about plans for an upcoming international conference of the three international working-class organizations, which would be held in April 1922. The First Plenum had viewed such a conference as a battleground in the campaign for a united front. Drawing a balance sheet of this whole experience was one of the central reasons for convening the Second Enlarged Plenum of June 1922.

The background of this conference helps explain why it generated considerable interest among the working-class public at the time.

The international workers’ movement in 1922 was divided into three main international currents: the Second International, the centrist ‘Two-and-a-Half International’ (formally the International Working Union of Socialist Parties), and the Third Communist International.20

In February 1922, the Comintern had been approached by the leadership of the Two-and-a-Half International proposing a world conference of the three Internationals to discuss the need to combat the capitalist offensive and the threat of war.

Despite its political opposition to the Social-Democratic and centrist world bodies, the Comintern leadership responded positively to the proposal, based on its support for united working-class action. Out of this initiative came the Conference of the Three Internationals, which took place in Berlin in early April 1922. The stated objective of this conference was to convene a world congress of labour that would include the major tendencies in the workers’ movement.

Among those who viewed the Berlin Conference with the greatest interest was Lenin. Recognising its importance for organizing united proletarian action, Lenin attempted to assist in the Comintern’s participation, giving practical advice to its delegation. Among Lenin’s suggestions was to minimise unnecessary obstacles – including in the language used. Referring to a resolution of the First Enlarged Plenum on participation in the Berlin Conference, Lenin wrote:

“My chief amendment is aimed at deleting the passage which calls the leaders of the II and II ½ Internationals accomplices of the world bourgeoisie. You might as well call a man a ‘jackass’. It is absolutely unreasonable to risk wrecking an affair of tremendous practical importance for the sake of giving oneself the extra pleasure of scolding scoundrels, whom we shall be scolding a thousand times at another place and time.”21

As Lenin saw it, the meeting would result either in concrete proletarian action, or in exposing reformist and centrist opposition to such action. In either case, he believed, the result would be advantageous to the Communist movement.

The Comintern delegation to the Berlin Conference was headed by Radek, Bukharin, and Zetkin, who each addressed the gathering.22

In the course of the meeting, the Communist delegation made various concessions in the interests of common action. At the same time, they were able to use the platform of the conference to publicly explain to the world’s working class why they supported united action with the very same forces who had betrayed the working class during the First World War and subsequently.

Out of the Berlin Conference came a common declaration, which called for the formation of a Committee of Nine (with three representatives from each International), charged with organizing the projected world congress of labour.23

At the conference, as well as afterward, the representatives from the Second International made clear their opposition to holding such a congress. In face of this opposition, and the Two-and-a-Half International’s refusal to force the issue, the Committee of Nine broke apart at its first and only meeting on 23 May 1922.

Lenin criticised some of the concessions the Comintern delegation had made at the Berlin Conference. But he did not back down from his support for the Communist International’s participation, and he recognised some of the positive achievements that came out of this participation. Highlighting the Communists’ success in propagandizing their views, Lenin asserted that ‘we have made some breach in the premises that were closed to us,’ adding:

“Communists must not stew in their own juice, but must learn to penetrate into prohibited premises where the representatives of the bourgeoisie are influencing the workers; and in this they must not shrink from making certain sacrifices and not be afraid of making mistakes, which, at first, are inevitable in every new and difficult undertaking.”24

In Radek’s report to the Second Enlarged Plenum drawing an overall positive assessment of the experience, he made the observation that through its participation and clear-cut stance at the Conference of the Three Internationals, the Comintern was earning a reputation within the working class as the force most in favour of united proletarian action. This reputation was to play an important part in the Comintern’s successes over the next year in the trade unions and other areas.

Advancing the United-Front Campaign

One of the other aims of the Second Enlarged Plenum was to draw an initial balance sheet of Communist parties’ united-front experiences, as well as to overcome hesitation by several of the parties that had opposed the policy and were still reluctant to carry it out, despite having promised to do so. Radek’s report spoke to this point, as did supplemental remarks by Zinoviev.

In the process, Comintern leaders also made two important political observations about the united front:

- their opposition to the united front, a number of leftist delegates had counterposed a “united front from below” to a “united front from above.” The Comintern leadership rejected such a dichotomy, pointing out that the two things could not be separated. Indeed, the idea of a “united front from below” was a negation of the very concept. If it were possible to achieve united proletarian action over the heads of the existing working-class organizations, then there would be no need for united fronts at all. Communists could simply call for united action in their own name. Radek spoke to this point at the Second Enlarged Plenum in June 1922. “A genuine united front will come into being when it leads the masses into struggle,” he explained. “Now the question is: How do we go to the masses? Anyone who now says, ‘united front from below’ misunderstands the situation.”25

- united front was envisioned as a tool for action in defence of working-class interests; it was not seen as an attempt to achieve a broader ‘organic unity’ of the participating organizations. As Lenin had pointed out, referring to the Conference of the Three Internationals, united fronts should be seen exclusively ‘for the sake of achieving possible practical unity of direct action.’26

Three Parties Spotlighted

Months earlier, the First Enlarged Plenum had organized a separate agenda point on the problems of the French Communist Party. The Second Enlarged Plenum did so too, along with agenda points on the Czechoslovak and Norwegian parties. These three parties had all come to the Communist International directly out of the Second International, and were each saddled with many Social-Democratic traditions.

France: The majority of the old French Socialist Party had voted to join the Comintern at its December 1920 congress in Tours, deciding to change its name to Communist Party. A minority (known as the ‘Dissidents’) split off and retained the old party name. While becoming a Communist Party in name, however, the new party in many respects still retained the traditions and structures of the old Socialist Party.

The French CP was divided into factions: a centre majority, led by the party’s leader Frossard, a left wing that was generally closer to Comintern positions, and a right wing.

The Second Enlarged Plenum heard a report on the French party given by Trotsky. Trotsky also drafted a resolution on the French CP that was adopted.27

– Norway. The Norwegian Labour Party was one of the first parties to affiliate to the Comintern in 1919, although it never changed its name. The NLP was the leading party of the working class in Norway, and had come directly out of the Second International. Organizationally, however, it was unique. It combined individual party membership with group affiliations through trade unions and other workers’ organizations. Within the Comintern, the NLP fought to maintain its basic traditions, agreeing to transform itself into a genuine Communist party but stalling on implementation of that decision. During 1922 and 1923, moreover, the party was embroiled in a faction fight between the party majority, led by Martin Tranmael, and a minority favouring closer ties with the Comintern, which also held the leadership of the youth organization.

– Czechoslovakia. The majority of the old Social-Democratic Party in Czechoslovakia had voted to join the Comintern in early 1921, with a Social-Democratic minority splitting off. But the new Communist Party remained divided by nationality within the new country of Czechoslovakia. With the Comintern’s help, these nationally divided Communist organizations united into a single party in late 1921. The united party was, nevertheless, embroiled in a factional struggle, paralysing much of its work. The Second Enlarged Plenum heard reports from the leaders of the two main factions, Bohumir Šmeral and Bohumil Jílek.28

Other Topics Discussed

Other matters were also taken up at the Second Enlarged Plenum:

– The trial of the Russian Socialist Revolutionaries. The plenum heard a report by Zinoviev on the trial that had just begun in Moscow of 47 members of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party, charged with maintaining ties with Anglo-French imperialism and being involved in armed counterrevolutionary attacks in Russia during the Civil War. The trial was being utilized by the Second and Two-and-a-Half Internationals in their campaign against Soviet Russia, and they raised it prominently at the Berlin Conference. As a result, the Communist delegation at Berlin announced that no death sentences would come out of the trial, and agreed to allow the Social Democrats to have open access to the trials, including functioning as defence counsels. At the same time, the plenum outlined a political campaign that Communist parties were urged to wage around the trial, which was to stress the Social Democrats’ support for armed counterrevolutionary acts committed against Soviet Russia.29

– In preparation for the Fourth World Congress, scheduled to be held four months later, the Second Enlarged Plenum elected a commission to prepare a programme for the Comintern.

Fourth World Congress

In November-December 1922, the Comintern held its Fourth Congress. One of the main themes of that congress was the united front.

In addition to approving the perspective adopted at the First and Second Enlarged ECCI Plenums, the congress discussed the united-front policy in a strategic framework. As Radek told the congress:

“[T]he application of the united-front tactic today seems to me to be somewhat different in character from what it was earlier. At first, the united-front tactic was a way to cover the broad retreat of the proletariat. Now, it seems to me that the united-front tactic is a protection for gathering and deploying our forces and for preparing a new advance.”30

At the Fourth Congress, the Comintern’s united-front perspective was broadened strategically in another way, with the call for an “anti-imperialist united front” in the colonial and semi-colonial world. Such a front, a congress resolution stated, would “promote the development of a revolutionary will and of class consciousness among the working masses, placing them in the front ranks of fighters not only against imperialism but also against survivals of feudalism.” And it added that “just as the slogan of proletarian united front in the West contributes to exposing Social-Democratic betrayal of proletarian interests, so too the slogan of anti-imperialist united front serves to expose the vacillation of different bourgeois-nationalist currents.”31

An additional application of the united front proposed at the Fourth Congress concerned the fight against fascism. The call for an anti-fascist united front originated from Fourth Congress delegates who were dissatisfied with the lack of a perspective by the ECCI leadership to combat the fascist rise. Swiss delegate Franz Welti told the congress that it “must demand of the parties of West and Central Europe that they undertake a coordinated effort on the basis of a proletarian united front, utilizing both parliamentary and extra-parliamentary methods, in order to erect a wall against fascism.”32 This idea, acknowledged toward the end of the Fourth Congress,33 would be at the centre of the discussion on fascism at the Third Enlarged Plenum.

The Fourth Congress also recognized the limits of the united-front slogan. It rejected seeing united fronts as electoral blocs or coalitions. As a resolution of the Fourth World Congress stated, “By no means does the united-front tactic mean so-called electoral alliances at the leadership level, in pursuit of one or another parliamentary goal.”34

Nevertheless, congress delegates frequently expressed different interpretations of the united front, with disagreements and reservations about its usefulness and applicability.35 •

Endnotes

- See p. 59.

- Zinoviev, in Riddell (ed.) 2012, 4WC, p. 97.

The ECCI was elected following each world congress, with a membership generally around thirty. This number was expanded at ‘enlarged plenums’ by inviting parties to send additional representatives. - The proceedings and resolutions of these four congresses have been published in English in a series edited by John Riddell. The volumes include: Founding the Communist International: Proceedings and Documents of the First Congress, March 1919 (hereafter 1WC) (New York: Pathfinder Press, 1987); Workers of the World and Oppressed Peoples, Unite! Proceedings and Documents of the Second Congress (hereafter 2WC) (New York: Pathfinder Press, 1991); To the Masses: Proceedings of the Third Congress of the Communist International, 1921 (hereafter 3WC) (Leiden: Brill, 2015); and Toward the United Front: Proceedings of the Fourth Congress of the Communist International, 1922 (hereafter 4WC) (Leiden: Brill, 2012).

- See p. 504.

- The First Congress of the Peoples of the East was held in Baku 31 August–7 September 1920; for the proceedings, see Riddell, ed., To See the Dawn: Baku, 1920 – First Congress of the Peoples of the East (New York: Pathfinder Press, 1993). The First Congress of the Toilers of the Far East was held in Moscow and Petrograd, 21 January–2 February 1922; for the proceedings, see John Sexton, Alliance of Adversaries: The Congress of the Toilers of the Far East (Leiden: Brill, 2018).

- In Riddell (ed.) 2015, 3WC, pp. 131–2.

- For the Open Letter and the ECCI debate on it, see Riddell (ed.) 2015, 3WC, pp. 1061–9. For Lenin’s position, see pp. 1086–7 and 1098–9.

- Riddell (ed.) 2015, 3WC, pp. 939–40.

- For the December 1921 theses on the united front, see pp. 254–64 of this volume.

- See p. 107–8.

- See p. 106.

- See pp. 119 and 128.

- See p. 149.

- See pp. 201–5.

- See pp. 181–2 and 183.

- See pp. 198–201.

- See pp. 185–97.

- See pp. 207–9.

- See pp. 217 and 219.

- The Second and Two-and-a-Half Internationals merged in May 1923. An additional international current at the time was that of the anarcho-syndicalist forces. In late 1922 these groups formed the International Working Men’s Association.

- See pp. 372.

- For the list of the entire Comintern delegation, see p. 366.

- For the text of this common declaration, see pp. 367–8.

- For Lenin’s assessment of the results of the Berlin Conference, see pp. 374–7.

- See pp. 284.

- See pp. 371.

- See pp. 310–9 and 351–8.

- See pp. 296–300.

- See pp. 269–71.

- Riddell (ed.) 2012, 4WC, p. 452.

- Riddell (ed.) 2012, 4WC, p. 1187.

- Riddell (ed.) 2012, 4WC, p. 476.

- Riddell (ed.) 2012, 4WC, pp. 20, 1154.

- Riddell (ed.) 2012, 4WC, p. 1158.

- See Riddell (ed.) 2012, 4WC, p. 9, as well as Trotsky, The First Five Years of the Communist International (New York: Pathfinder Press, 1972), vol. 2, p. 92.