The Climate Crisis and the Crisis of Stranded Fossil Fuel Assets

The world’s oil, gas, and coal companies would incur what the Financial Times (FT) recently described as “breathtaking” losses if they’re not allowed to extract and burn their enormous reserves.

In total, fossil fuel CO2 emissions contained in untapped reserves are estimated at 2910 gigatonnes (GT) or nearly three trillion metric tons. To put that number in context, a sole GT is twice the mass of the global human population and enough to stretch 200 million elephants from the earth to the moon. The FT estimates that more than half these assets would be stranded if the 2°C global warming target set by the 2015 Paris Agreement were met.

Assets held by ExxonMobil, Saudi Aramco, Total SA, Royal Dutch Shell and other corporations include rights purchased to explore in a given area as well as reserves under wells and other infrastructure already producing hydrocarbons. In the unlikely event the rise in temperature was more drastically curtailed to 1.5°C, more than 80 per cent of these assets would be rendered worthless. This would inflict losses of nearly a trillion dollars on shareholders, or about one-third of the current valuation of the world’s major oil and gas companies.

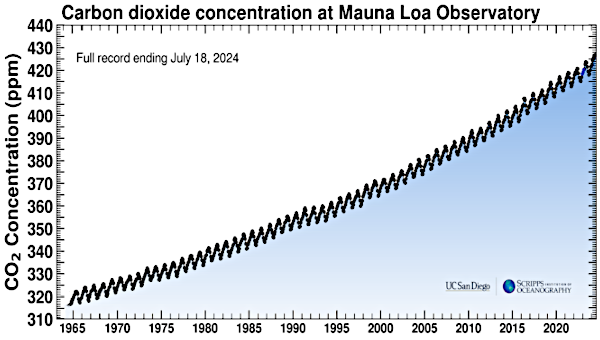

About 33 GT of carbon emissions were released in 2019, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). If the annual rate of emissions were frozen at that level, a further 2640 GT would still be burnt by century’s end, well beyond the target of 1200 GT which the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change assumes is necessary to hold the rise in global warming to 2°C. To meet the more ambitious 1.5°C limit, only 464 GT of the estimated 2910 GT of CO2 in the remaining oil, gas and coal assets could be burnt. Producers with the highest carbon intensity in their oil and gas reserves, notably those in the Canadian tar sands, would be hit hardest.

Foot-Dragging

The massive scale of the potential losses explains the refusal or foot-dragging by governments beholden to the industry to implement the Paris Agreement. The agreement is already regarded by climate scientists as inadequate to meet the climate emergency.

Still, the threat of tougher regulation leading to some percentage of stranded assets has been enough to spook major investors, especially as the pressure to curtail emissions rises with each flood, hurricane, firestorm, and other extreme weather event associated with climate change.

The coal sector, the largest emitter, has experienced the most capital flight, but oil and gas are not far behind. “As the first target for asset owners keen to decarbonize their portfolios, coal miners have performed disastrously over the past decade. Bloomberg’s index of global coal miners, the largest of which are in China, has plunged 74 per cent from its peak in early 2011… Collectively, world oil and gas company market values have fallen about half as much as coal miners since their own decade peak in 2011.”

If the present trend continues, the shift in energy investment from fossil fuels to renewables “would be one of the biggest ever shifts in the allocation of capital,” according to the FT. But even if it occurs it’s certain to fall well short of what is urgently required to avert catastrophic climate change. Despite all the noise emanating from governments, central banks, and investors over the past decade, the IEA says capital expenditures by the largest oil and gas companies directed to wind, solar, and other renewables still represents less than 1 per cent of their holdings.

All of which lends support to the program advanced by ecosocialists and various proponents of a Green New Deal – public ownership of the energy industry as a precondition for a rapid conversion to clean energy and a radical restructuring of the capitalist economy. •