The United Auto Workers and the Big Three Automakers: A Tale of Corruption

What follows is a somewhat complex tale of what happens when a labor union, structured to be unaccountable to the rank-and-file membership, embraces a system of labor-management cooperation rather than a class-conscious understanding that workers and their employers are adversaries with fundamentally opposed goals and desires. Unfortunately, what is true of the United Auto Workers (UAW) is true for many US labor unions. That the UAW, an iconic union, born of heroic class struggle, could sink into corruption, with a bloated and dictatorial bureaucracy, only shows in microcosm what ails much of organized labor in the United States. And just how difficult it will be to rebuild a labor movement worthy of the name.

“Ideals get tarnished quickly under the corrosion of material prosperity.”

— Walter Reuther1

The UAW and the Big Three automakers, General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler, have established a series of joint programs (described below), serving a variety of interests, all purportedly aimed at benefiting union members. The funds that support these programs amount to hundreds of millions of dollars, funded in various ways but never overseen in a transparent and public way. One program is aimed at training workers. However, the enormous sums involved were enticing to those who saw opportunities to pocket the money. Here is an example.

The lack of public oversight of joint training funds produced a “culture of corruption” among the UAW-Chrysler National Training Center (NTC) directors that led to bribery, theft, influence peddling, and a cover-up of criminal activity. The case filed in US District Court, Eastern District of Michigan, Southern Division charged that Fiat Chrysler Vice President Alphons Iacobelli and UAW Vice President of the Chrysler department General Holiefield violated the Labor-Management Relations Act (LMRA). One provision of the LMRA sought to prevent corruption of the collective bargaining process that occurs when an employer gives something of value to the union representative, presumably to influence the representative to ignore his or her duty to promote the interests of union members.

Management and Union Reps

Iacobelli and Holiefield and their cronies embezzled $4.5-million of joint training funds from the NTC to pay for items that varied in value from shoes, purses, and luggage to $2180 Belgian shotgun, $37,500 solid-gold Mont Blanc fountain pens, and a Ferrari sports car. Over $200,000 worth of purchases were charged to Holiefield’s NTC credit card including jewelry, furniture, and other personal expenses. NTC funds paid for over $262,000 on his mortgage. Iacobelli encouraged training center staff to use NTC-issued credit cards for personal purchases, to keep senior members of the UAW Chrysler Department “fat, dumb, and happy,” “take company friendly positions,” and to pay off co-conspirators to cover it all up. UAW President Dennis Williams declared that he was “appalled” by conduct that amounted to “betrayal of trust by a former member of our union.” Besides, the “NTC is a separate entity from the UAW that receives no union dues, the fact is the abuses alleged in the indictment dishonored the union and the values we have upheld for more than 80 years.” Holiefield retired in 2014 and died the following year.2

Norwood Jewell continued the General’s criminal enterprise when he took over the UAW Chrysler Department in 2014.Fiat Chrysler of America (FCA) management welcomed Jewell to the Chrysler department with a decadent party paid for with $30,000 of NTC training funds. The party featured “ultra-premium liquor, more than $7000 worth of cigars, and more than $3000 worth of wine with custom labels” emblazoned with Jewell’s name. Scantily clad “strolling models” lit UAW leaders’ cigars. FCA executives authorized Holiefield, Jewell, and other UAW officials to offer sham “special assignment” jobs at the NTC to their friends, family, and allies. The NTC transferred hundreds of thousands of dollars of fraudulent payments to the UAW to cover salaries and benefits to specially assigned individuals who did little or no work for the NTC. Jewell lived a luxurious lifestyle spending thousands of dollars of NTC funds at fancy steakhouses and luxury golf resorts in Palm Springs, California. He resigned in January 2018 after the FBI searched his home and pled guilty to violating LMRA on April 2, 2019. Jewell’s attorney begged for leniency at the sentencing hearing arguing his client was a victim of a corrupt culture in the union. The judge rejected the “everybody was doing it argument” and sentenced Jewell to 15 months in prison. Even though Jewel retired in January 2018 he received $219,495 from the international UAW for the year – about four times the annual wages of a shop floor autoworker. In retirement, Jewell receives dual pensions – one from GM and a more generous pension from the international UAW with COLA adjustments. Nancy Johnson, Jewell’s top assistant implicated him, Williams, and other UAW officials in misconduct as the federal investigation expanded to the General Motors and Ford joint training centers.3

The federal probe into the GM training center produced criminal charges of a retired aid to two former UAW GM Department vice presidents. Michael Grimes, the former administrative assistant to Joe Ashton and Cindy Estrada was the ninth person to be charged in the corruption investigation. He was charged with wire fraud conspiracy and money laundering for receiving a $1.99-million in kickbacks from suppliers of “trinkets and trash.” Grimes served on the board of the UAW-GM training center with Ashton and Estrada. Training funds paid for jackets, backpacks, and a $3.97-million contract to a vendor for 58,000 watches. The watches are being stored in a warehouse at the GM training center.4

The problem with the bribery scheme described in the federal corruption case was that UAW officials were already “fat, dumb, and happy.” The political faction that has been in control of the UAW for more than seventy years, the Administration Caucus, established a system of institutional corruption when they collaborated with management in 1982 to form nonprofit corporations with GM, Ford, and Chrysler to administer joint programs (jointness) created in the UAW national agreements.The Big Three automakers bankrolled the programs with “Joint funds.” Williams stated that the NTC received no union dues from the UAW. That is true, but over $387-million in “Joint Funds Reimbursements” (JFRs) were funneled through the training centers into UAW coffers since 2005.The UAW has received nearly $88-million in JFRs from the NTC, nearly $140-million in JFRs from the UAW-Ford National Development Training Center (FDTC), and nearly $159-million in JFRs from the UAW-GM Center for Human Resources (CHR) since 2005.5 GM spent $3-billion on joint programs between 1982 and 2000. Ford and Chrysler reported spending more than $1.3-billion on joint programs between 1996 and 1999. The training centers transferred hundreds of millions of dollars into the UAW since 1982 but they were not clearly reported to the Department of Labor until 2005.6 The labor-management cooperation schemes subverted laws intended to prevent employer interference in unions. The jointness regime formed a parallel bureaucracy staffed by “joint programs representatives,” appointed by the UAW president and approved by management.Joint representatives are an abundant source of employer-funded political patronage within the UAW.7 I call this peculiar arrangement, “UAW Incorporated.” UAW Inc. was presented to the rank-and-file as a win-win strategy to make the automakers more competitive, and thereby provide job security. The outcomes of joint labor-management cooperation schemes produced the opposite; corporate market share and employment levels plummeted.

The Demise of a Once Great Union

Walter Reuther Embraces Cooperation

This is the story of how the UAW, one of America’s most progressive and corruption-free labor unions, was transformed by cooperative labor-management schemes from a membership-driven to a capital-driven organization. The UAW captured the world’s imagination in 1936 when workers at the sprawling Fisher Body-I plant in Flint, Michigan led by a coalition of Socialist and Communist strategists, sat down on their jobs and forced the mighty General Motors Corporation to recognize the union. The Flint sit-down strike inspired a wave of union organizing that swept into every business sector across America. By the middle of the twentieth century more than one third of private-sector workers were union members. The UAW functioned as an arm of corporate labor relations by the end of the century.

Walter Reuther was elected UAW president in 1946 and held office until an untimely death in a plane crash in 1970. In a break from his socialist past, Reuther rejected class-based unionism and became an adherent of Samuel Gompers-style business unionism, choosing to work within the capitalist system. He hoped not to replace capitalism but to transform it into a more humane economic system. The 1950 “Treaty of Detroit,” a five-year billion-dollar wage and benefit package negotiated by the UAW and GM won pension and health-care provisions, Cost of Living Allowance (COLA) increases, and Annual Income Factor (AIF) wage protections that became the pattern for labor agreements across the country.8

Success at the bargaining table ironically contributed to the labor movement’s demise. Contract gains that lifted the rank-and-file into a middle-class lifestyle separated them from the class struggle that made it all possible. The UAW leadership and the workers lost touch with the union’s organizing principles and identified more with management as labor conflict shifted from the point of production to the front office.

The post-Second World War economy delivered prosperity, and this seemed to justify the UAW’s cooperative approach. The postwar labor-capital consensus fractured in the 1970s, and this led to aggressive corporate attacks. The purge of key militants, almost all left-wingers during the Reuther years deprived the UAW of its ability to resist management’s offensive. Instead of fighting back, the UAW leadership adopted a policy of promoting corporate competitiveness. Untrammeled by the quaint notion of rank-and-file solidarity, the Administration Caucus, abandoned constitutional objectives “to improve working conditions, create a uniform system of shorter hours, higher wages, healthcare and pensions; to maintain and protect the interests of workers”when they adopted jointness.9 The jointness framework enabled the Big Three US automakers to transfer hundreds of millions of dollars into the UAW. The influx of joint funds into the UAW supplemented the loss of dues paying members as the Big Three downsized.

Cooperation Deepens and Corruption Mounts

UAW and GM officials extolled the virtues of mutual respect, teamwork and shared gains when Quality of Work Life was inserted into the national agreement in 1973 by Irving Bluestone, UAW Director of the GM Department. Bluestone intended QWL to be a foothold for industrial democracy in the factories. For Bluestone, QWL was a step toward worker-control of the shop floor.

When Stephen Yokich took over the UAW GM Department in 1986, he resolved to replace QWL with “Quality Network,” (QN) a product-centered program designed to improve product quality, productivity, and facilitate cost-cutting. QN expanded the UAW bureaucracy with an elaborate system of labor-management committees to administer dozens of joint “action strategies,” each one administered by appointed representatives. Despite the promise of mutual gains, GM lost 10 percent of its market share and shed 127,000 workers in the 1980s. When GM entered bankruptcy in 2009, GM’s market share was 22 percent, roughly half the level when the cooperation scheme began in 1982, and only 69,000 hourly workers remained of the 441,000 who were on the job in 1981.10

Considering the ongoing losses to the stakeholders, why did the union and management continue the labor-cooperation scheme? Why would the UAW continue the partnership with the Big Three after losing nearly three-quarters of its membership? Why would GM continue to transfer hundreds of millions of dollars of joint funds into the UAW even though its market share continued to decline? Joint programs were a bargain for management. The Big Three purchased labor peace with JFRs to the UAW, while cutting hundreds of thousands of jobs. The Administration Caucus became a reliable partner in the downsizing of GM operations in exchange for preserving, expanding, and financing the UAW bureaucracy.

The UAW also created nonprofit training entities controlled entirely by UAW. For example, UAW president, Bob King and secretary-treasurer, Dennis Williams were the two-person board of directors for the “International UAW Region 9 New York Training Initiative,” a nonprofit tasked with training Perry’s Ice Cream workers on “new equipment and technology.” The State of New York Department of Labor was the sole-source of revenue for the “Training Initiative.” The Training Initiative designated Perry’s Ice Cream Company as the training contractor for its own workers. State of New York provided $939,840 in training grants to the Training Initiative in 2010, 2011, and 2012. The Training Initiative paid $579,463 to Perry Ice Cream to train 127 workers during the same period. When Perry’s Ice Cream celebrated its 95th anniversary in 2013, the firm must have had the best-trained ice cream makers in the history of making ice cream.11 This bizarre relationship between labor and management was conceived during the heyday of jointness in the auto industry.

Democracy, UAW-Style

The corruption on display at the NTC is rooted in the political machine that has dominated the UAW since Walter Reuther was elected president in 1946. After Reuther was reelected the following year his Reuther Caucus, renamed the Administration Caucus, transformed the UAW government into a single-party state.The Public Review Board (PRB), the UAW ethical oversight body, described the International UAW as a “one-party institution like many national governments in which a single-political party controls the government and the officials who formally make and administer those laws are selected entirely by that party.” For several decades, “the lines of demarcation between party, the Administration Caucus, and the formal governing body, the International Executive Board (IEB), have become blurred, for 100 percent of its personnel are, and traditionally have been, members of the Administration Caucus.” Reuther’s political machine rewarded partisan loyalty and undermined internal democracy. Opposition activists who challenged UAW policy were crushed – sometimes violently.12

The workers who entered the factories in the 1960s were more willing than their elders to challenge union leaders. When the grievance procedure failed to provide relief for workers, many took matters into their own hands. The civil rights struggle that was unfolding in the streets of Detroit inspired shop floor activism that alarmed Solidarity House. Black Nationalist ideology that erupted in the Detroit plants in 1968 inspired the Revolutionary Union Movement (RUM) to spread to Dodge (DRUM), Ford (FRUM), and General Motors (GRUM). As wild-cat strikes spread from one plant to another, the International UAW declared war on Black activists. When members of UAW Local 212 walked out of the Mack Stamping plant in 1973, the international UAW and management joined forces to suppress the strikers. After workers defied the UAW’s order to return to work, several hundred UAW officials armed with baseball bats attacked the picketers – ending the strike. None of the safety concerns that triggered the walkout were resolved, and only half of the 75 workers who were fired were reinstated.13

Chaos at GM’s “plant of the future” in Lordstown, Ohio echoed conditions in the Detroit Chrysler plants. The Lordstown plant was GM’s sole producer of the Japanese import fighter, the subcompact Chevrolet Vega in 1969. GM’s Southern Strategy, moving production to southern states to avoid Detroit unions ran smack into another labor stronghold. The work force was mainly white sons of former Mahoning Valley steelworkers. A host of robots applied 520 welds to each car on the fastest assembly line in the United States, capable of producing a hundred cars per hour. When the grievance procedure failed to resolve workers’ complaints of speed-ups and dangerous conditions, cars rolled off the assembly line severely damaged. The UAW responded sympathetically to the “Lordstown Syndrome” or the “blue-collar blues” caused by the same conditions that inspired the rise of the RUM by leading a twenty-two-day strike against GM with UAW Local 1112. Lordstown militants were treated like heroes. Their grievances were resolved in contrast to Black Chrysler workers who were treated as outlaws.14

The Administration Caucus controls the agenda from local union meetings to the constitutional conventions with judicious use of parliamentary procedure. Loyal partisans pack union meetings in order to advance the party line. Insubordination was not tolerated. In 1986, UAW Region 5 Assistant Director, Jerry Tucker defied the Administration Caucus when he decided to run against his boss Ken Worley. UAW president, Owen Bieber, promptly fired him from the position of Assistant Director, declaring falsely that Tucker was in violation of the UAW Constitution. Worley was declared the winner at the convention, but Tucker learned the election was stolen. An investigation by the Department of Labor (DOL) revealed 28 votes were illegally cast for the incumbent. The US Justice Department subsequently filed three lawsuits on election violations against the UAW. A federal judge to declare the election illegal two years later. In September of 1988, Tucker won the DOL supervised rerun of the election, but the IEB made it impossible for him to function as Region 5 Director. He was defeated in the next election.15

The UAW Faces the End of the Post Second World War Prosperity

A convergence of political and economic events triggered the unraveling of more than forty years of collective bargaining gains by private-sector workers in the United States. The 1980s was a decade of transformation for the UAW and General Motors. For the first time since the 1930s, the union and the corporation faced existential threats that coincided with the worst economic recession since the Great Depression. It was the decade of the “Reagan revolution.” Ronald Reagan was elected president promising to “get government off the backs of the people” by dismantling fifty years of progressive federal policies. He attacked social programs and the institutions working class Americans relied on. Reagan’s confrontation with the Professional Air Traffic Controller Organization (PATCO) in 1981 foreshadowed the decline of organized labor. PATCO endorsed Reagan for President in the 1980 because the leadership interpreted his pledge “to you that my administration will work very closely with you to bring about the spirit of cooperation” as a promise of contract gains. When the air controllers walked off the job a year later over wage demands, Reagan fired them all. Emboldened by the PATCO firings and distressed economy, employers rolled back workers’ gains at the bargaining table. With the deindustrialization of America well underway, concessionary bargaining became the new pattern bargaining in the auto industry.16 “Reaganomics” benefitted capital interests by reducing taxes, regulations, and the social welfare programs that conservatives had long-blamed for crippling the economy. The unfettered economy was supposed to trigger a “trickle-down effect” of wealth through society but launched a modern Gilded Age instead. The Reagan revolution was the ideal political environment for the imminent assault on organized labor.

The increase of global competition in the 1970s ended the post-Second World War monopoly profits of US corporations and changed industrial labor relations forever. Seventy percent of the goods sold in the United States by 1980 had direct import competition. Back-to-back oil crises triggered by the Yom Kippur War in 1973 and the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran contributed to a stock market crash and soaring inflation. OPEC-driven oil price increases sent inflation spiraling upward to 12.3 percent in 1975. The Federal Reserve chairman, Paul Volker, doubled the Fed Reserve Rate to combat inflation. Inflation was reduced, but in 1981 the economy was mired in a deep recession.17 The crisis in the auto industry pushed Ford and Chrysler to the brink of bankruptcy and delivered General Motors its first loss since 1921. The Big Three closed down twenty facilities between 1979 and 1980 that employed over 50,000 workers. An additional 80,000 workers lost their jobs when suppliers to the industry closed nearly 100 plants.18 The US Congress passed the Chrysler Loan Guarantee Bill securing $1.5-billion for the troubled automaker in 1979. The Chrysler relief plan included $203-million in UAW wage concessions and the deferral of $200-million in pension fund payments as a condition of congressional action. After the dust settled, Chrysler workers earned $2,000 less than workers at Ford and GM over the three-year contract. Ford and General Motors pressured the UAW into additional concessions arguing the Chrysler agreement left them at a disadvantage. Even though GM cleared $333-million in profits in 1981, the UAW agreed to reopen the 1979 GM contract seven months early. GM had twenty-five assembly plants in 1982; six plants were closed, five were reduced to one shift, and five operated at reduced line speeds. With the threat of more plant closings, the UAW agreed to $2.5-billion in concessions in the 1982 GM-UAW national agreement.The 2 ½ year agreement introduced “joint programs” into the industry lexicon.19

Congress acted in 1978 to encourage labor-management cooperation and to promote labor peace. The Labor-Management Cooperation Act of 1978 (LMCA) was a self-contained amendment to the NLRA that encouraged joint labor-management cooperation in union shops. The UAW and the Big Three automakers used the LMCA as the legal basis to establish joint nonprofit corporations to administer joint activities and the joint funds used to finance the programs without having to comply with the federal “audit inspection requirement.”20 The lack of an audit requirement enabled the UAW and the Big Three carmakers to sidestep employer prohibitions to interfere with or provide financing to unions – rules intended to discourage company-dominated unions. Social, political, and economic turmoil during the Great Depression led labor law reforms that encouraged collective bargaining and prohibited company unions. The absence of an “audit inspection requirement” in the LMCA allowed for the return of a more insidious form of company unionism exempt from any form of financial oversight.

The Trajectory of Cooperation in the UAW

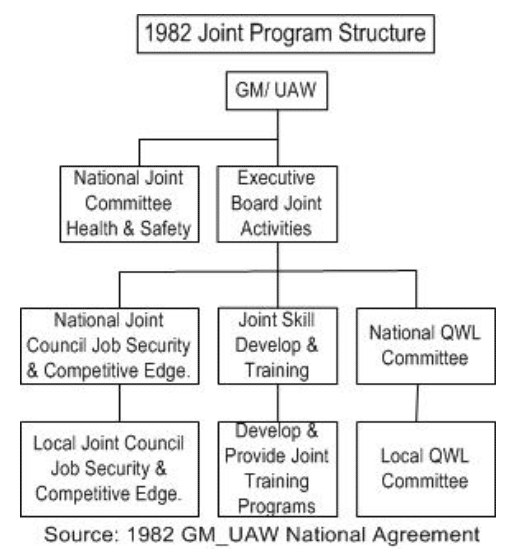

Jointness bargaining was a trend that began in the 1980s concessionary agreements between the UAW and the Big Three. In 1982, jointness was defined as a recognition for “improved communication and better understanding of each other’s concerns.” GM agreed to consider employee input before deciding on any future outsourcing.The 1982 GM-UAW national agreement highlights announced, the “Contract strengthens worker input into the management decision-making” by adding three new labor-management committees to the existing local and national Committee to Improve the Quality of Work Life. (figure 1). The UAW leadership claimed more cooperation would preserve jobs through shared decision-making, but it wasn’t. GM never wavered from the exclusive right to “hire; promote; discharge or discipline for cause; and to maintain discipline and efficiency of employees,” in addition “products to be manufactured, the location of plants, the schedules of production, the methods, processes and means of manufacturing are solely and exclusively the responsibility of the Corporation.”21

A formula based on the number of active workers and excessive overtime generated “joint funds” to pay for joint program representatives, training, and health and safety programs. The growing list of committees were staffed by an equal number of UAW and management appointed representatives. Appointed jobs were highly sought-after positions because of the lucrative pay and benefits. Loyal partisans traded in their coveralls and the assembly line for Polo-shirts, clipboards, and a desk. The Administration Caucus used joint programs as an opportunity to appoint scores of new joint program representatives, expand the union bureaucracy at the national, regional, and individual plant level. Joint programs created plant-level team leaders who were union-endorsed straw bosses who functioned as shop floor foremen without management credentials. The wages and benefits of appointed representatives assigned to the training centers by the UAW administration were fully reimbursed (JFRs) to the union from the training centers. Joint programs expanded to the point where appointed UAW-GM representatives outnumbered traditional elected representatives.22

The nonprofit corporations were created to administer joint programs established in the national bargaining agreements between the UAW and GM, Ford, and Chrysler. All three car companies incorporated nonprofits with the UAW as early as 1982. The Ford training center was incorporated in 1982 and the Chrysler training center was incorporated in 1986. However, the evolution of the GM training center offers the most insight into the growth of UAW Inc. The first UAW-GM joint non-profit was organized in 1983 as a 501(c)(3) public charity created in an alliance with the State of Michigan called the “GM-UAW Metropolitan Pontiac Retraining and Employment Program (MPREP).” MPREP was dissolved and the assets were rolled into the UAW-GM Skill Development and Training Program (SDTP) that was formed in 1984. The SDTP was renamed UAW-GM Human Resource Center (HRC) in 1985. A $5.5-million office complex to house the HRC was constructed at the campus of Oakland Community College in Auburn Hills, Michigan. The HRC remained a 501(c)(3) public charity until the IRS revoked the public charity status because General Motors was the sole source of funding and was replaced by the UAW-GM Center for Human Resources, a 501(c)(3) private foundation in 1994.23 Similar nonprofits were formed by the UAW and John Deere, Caterpillar, Boeing, and Rockwell International. UAW leaders created several other 501(c)(3) training corporations exclusively controlled by the union and publicly funded by state and federal grants that became popular in the 1980s to assist workers displaced by foreign competition.

The push for joint programs gained momentum when Alfred S. Warren Jr. became GM vice-president of industrial relations. His counterpart in the union was Don Ephlin, UAW Vice President of the GM Department. Warren promoted joint programs as a long-term strategy to roll back UAW wage and benefit gains. His strategy depended on expanding “joint problem-solving strategies” to achieve worker buy-in to variable wage layers, benefits reductions, and the elimination of income security formulas such as Guaranteed Income Stream (GIS), Cost of Living Allowance (COLA), and the Annual Improvement Factor (AIF).24 Warren presented the details of his strategy to GM personnel directors titled “Actions to Influence the Outcome of Bargaining” in 1983.

The “Warren Strategy” spelled out the main bargaining objectives for the 1984 negotiations. The first objective was to reduce labor costs by eliminating COLA, AIF, GIS, and implementing multi-tier wages. The second objective was to cut labor costs by changing work and seniority rules, reducing skilled trades classifications, introducing new technology, and eliminating job security. The third objective was to make outsourcing easier. The fourth objective was to promote more joint programs, expanding labor-management committees, and replacing the cyclical local bargaining with open-ended “Living Agreements.” The fifth objective emphasized individual accountability, and the adoption of judicial joint “pay for knowledge” systems.25 Warren’s genius was in his ability to persuade the UAW to expand joint programs with promises of jobs security, while GM methodically reduced the workforce and eliminated wage and benefit protections.

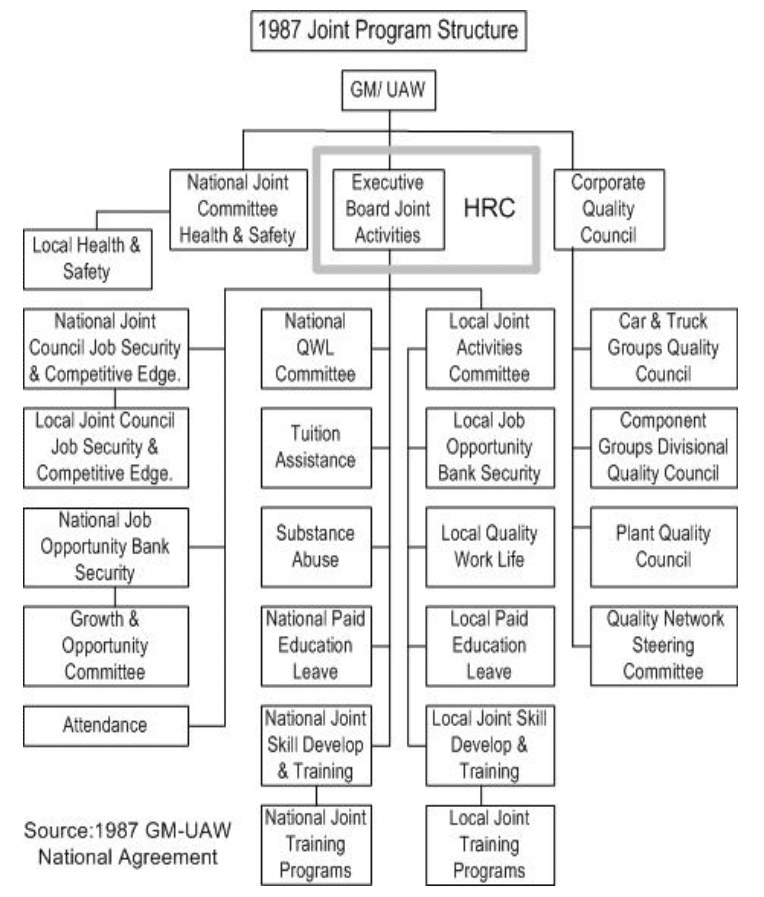

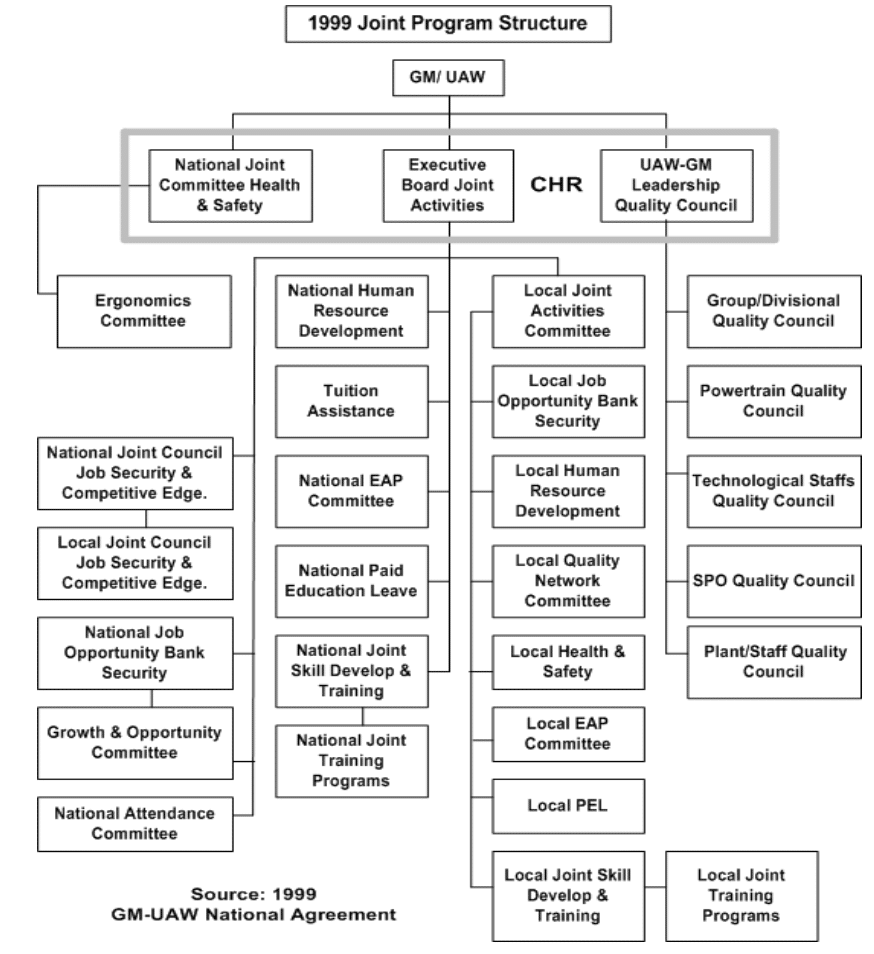

Quality of Work Life, a worker-centered program was replaced by Quality Network (QN), a product-centered joint program in the 1987 GM-UAW National Agreement. QN stressed product quality, productivity, and continuous improvement. While QN was clothed in a rhetoric of product quality and job security, the focus of joint programs shifted from workers to the corporate bottom line. Several new labor-management committees were added to the growing joint bureaucracy. (Figure 2) The Job Opportunity Bank Security (JOBS) program was supposed to stem the loss of GM job cuts unrelated to market downturns. Eligible laid-off workers were placed into the “JOBS Bank,” and were paid from a special JOBS fund.26 The JOBS program was jointly administered, but GM abused the system by assigning JOBS Bank workers to understaffed factories. GM plants were cutting payrolls while quietly using laid-off workers from the JOBS Bank.27

The jointness apparatus quadrupled in size by 1999. The UAW-GM Center for Human Resources built a new $300-million training center along the bank of the Detroit River at 200 Walker Street in 2001. The 420,000-square foot seven-story office tower was located on a sixteen-acre site that included a 900-car parking deck. The training center included a 400-seat auditorium with Internet access from every seat.28 UAW Inc. was thriving, but the rank-and-file continued to suffer job loss and GM continued to lose market share. The GM-UAW workforce was 198,585 and GM controlled 29.2 percent of the US market in 1999. One year later, another 20,000 workers were gone forever, and GM’s market share was at 28 percent.29 The promise of labor-management cooperation failed workers and corporate stakeholders, but the UAW-GM joint bureaucracy was booming. (See figure 3)

Revolts in the Ranks

Management abuse of joint programs and concessions triggered a political backlash in local unions across the country. The consequences were severe for local union leaders in the Flint area who strongly supported QWL programs. Buick UAW Local 599 President Al Christner gained national notoriety for using QWL programs to transform the dying Buick foundry into Factory 81, a state-of-the-art torque converter factory. The renaissance of the Buick foundry became a model for building Buick City. Local 599 faced the dim prospect of losing the entire Buick complex and 14,000 jobs when GM announced it was going to close final assembly and the old foundry. Buick workers had a militant reputation, and management considered foundry workers the worst. Christner and his management counterpart, Bill Rowland, implemented the largely unused Quality of Work Life contract provision to overhaul troubled labor relations.30 Using the same foundry workers management once considered a lost cause, Factory 81 became a showplace for labor-management cooperation. Christner and Rowland emphasized the success of Factory 81 to convince GM executives to accept a proposal to convert final assembly into Buick City.

However, the cordial relations that were the foundation of Buick City deteriorated. The partnership that saved the Buick assembly plant was an aberration. The true believers within management were replaced by hard-core company men. Shop floor warfare returned. Workers at Flint Chevrolet Truck Assembly were stunned to learn that the plant superintendent had a secret button installed to speed up the assembly line. The truck plant UAW Local 598 leaders called the incident “Chevy-gate” because management claimed, “production tapes went missing,” just like “Nixon’s missing 18-minute tape.” The Flint Journal urged Local 598 members not to let the secret button interfere with QWL programs – to put it behind them as though nothing happened. The illegal speed-up nearly triggered a strike. Christner and the presidents of four other local unions in the Flint area who started QWL programs were turned out of office in 1984. Christner would never see the inside of Buick City, the plant he helped create.31

The UAW’s 50th anniversary celebration was scarred by prejudice, corruption, and violence as opposing forces converged on the1986 28th UAW Constitutional Convention in Anaheim, California. Disgruntled workers from Locals Opposed to Concessions (LOC), the National Rank-And-File against Concessions (NRFAC), and the nascent New Directions Movement (NDM) worried that the UAW was becoming a company union.32 Opposition delegates were insulted, humiliated, and beaten. Shunned by the international UAW, Victor Reuther wasn’t allowed to speak at the convention because of his outspoken criticism of the recent Saturn agreement. David Yettaw was among the delegates from UAW Local 599 representing the sprawling Buick City complex in Flint, Michigan. A seasoned union activist, Yettaw served as committeeman in Buick final assembly from 1972 until 1984 when he was elected the local union Education Director. Yettaw participated in the founding conferences of LOC and the NRFAC, but nothing prepared him for what happened on the convention floor:

There were all kinds of leaflets and stuff being passed out – and I have an open mind. I was taking literature from everyone who was passing it out. There were people from the far Right, NRA and there’s people there from the far left – the Socialists and there were Communists and Trotskyites. And I took some literature of Jerry Tucker’s New Directions. I’ll never forget this Sergeant at Arms at the UAW convention. He doesn’t know me, and I don’t know him. He says, “You aren’t taking that Communist literature, are you?” I said, “Well I don’t know Region 5 – I didn’t even know these people.” And he said, “Yeah, you see that guy’s picture right there?” I said, “Yeah.” He said, “Well that’s Jerry Tucker, and he’s married to that nigger Aunt Jemima.” And I thought, Jesus Christ – I don’t care if a guy’s wife is polka dot, that’s his business. Then there was a fight. One of those Administrative Caucus guys beat up this woman from Region 5. That was my first dose of the Administration Caucus.33

In the fall of 1989, activists from around the country met in St. Louis at the first NDM convention to officially inaugurate the UAW New Directions Movement.34 Victor Reuther joined NDM after the UAW administration’s role in illegal election activity was exposed.Speaking at a labor conference of over 400 people in Flint sponsored by Autoworkers Against Concessions, Reuther endorsed the national NDM platform that included: a constitutional amendment to replace the delegate process with “one member, one vote” for UAW officers, election of currently appointed representatives, abandoning the competitive bargaining strategy, and the conversion of Joint Funds into worker wages and benefits. Tucker challenged Owen Bieber for UAW president at the 1992 convention but was denied the opportunity to address the delegates. He was soundly defeated by Bieber.35 Shaken by Victor Reuther’s support of NDM, the UAW administration published an “Open Response to Victor Reuther,” co-signed by five former UAW presidents and vice-presidents. The letter condemned Reuther because he chose “to associate himself with the very group in the UAW which has opposed practically all of his brother’s policies and programs.”36 Victor Reuther’s offense was to question which side the UAW administration was on because the Saturn agreement did away with wage and benefits gains won by Walter.

Dave Yettaw joined NDM a few months after getting elected to president of the UAW Local 599 in 1987. “I never fell for that Quality of Work Life scam” he declared reflecting on a lifetime of union activism. Having served as a three-term president of Local 599, Yettaw was always skeptical of management’s promises of job security – “that’s not how they work.”37 His leadership role in NDM invited a fierce attack from the Administration Caucus. Solidarity House mounted a well-financed smear campaign to removed Yettaw from office in 1996. Unity Caucus, the Administration Caucus rump organization at Local 599 joined with the local Chamber of Commerce, Flint Journal, and the Mayor of Flint to deny Yettaw a fourth term. The coalition warned workers if Yettaw was reelected, it would be the end of Buick City. Yettaw was defeated, and GM announced the closing of Buick City six months later. The legacy of jointness was littered with broken promises and closed factories. The UAW leadership made promises they couldn’t deliver, and the carmakers made promises they didn’t intend to keep.

The Warren strategy that was proposed to GM executives in 1983 was fully realized when Rick Wagner steered GM into bankruptcy. Warren’s success hinged on the collaboration of the UAW administration and expanding joint programs. Jointness provisions grew from three pages in 1973 GM-UAW national agreement to more than 200 in 1999. The 2007 GM-UAW national agreement eliminated defined pensions for new-hires and cut entry-level wages nearly in half.38 The Warren strategy successfully reduced skilled trades classifications, eliminated job security provisions, and increased outsourcing. Pay for knowledge, multi-tier wages, the elimination of income security and seniority protections destroyed trade union principles of equal pay for equal work. Joint Programs didn’t preserve jobs, make General Motors competitive, or avoid bankruptcy.

General Motors emerged from bankruptcy financed by the federal government with less than 50,000 workers. The UAW joint bureaucracy remained intact, but workers had to accept more concessions. The UAW “bankruptcy agreement” included alternative work schedules, changes to overtime, shop rule changes, and a new category of low-pay, part-time workers called “flex temporary employees.” Flex-temps didn’t accumulate seniority because they were not GM employees. They were utilized as day laborers, on par with those commonly employed in agriculture. Retiree health care costs were shifted off GM’s books into an independent trust fund. The joint programs bureaucracy remained, but the benefits for workers were eliminated or reduced. Taxpayers indirectly subsidized the jointness scheme when GM and Chrysler were bailed out by the federal government. The GM and Chrysler bankruptcies had no effect on UAW Incorporated revenue. The tens of millions of dollars continued to flow through the training centers into the UAW uninterrupted by the bankruptcy.39

The Future?

Labor concessions and the labor-management cooperation schemes have delivered the workforce GM demanded in the 1983 Warren strategy. UAW contracts conceded multiple wage-layered workers – First-tier “legacy” workers with full wages and benefits, second-tier workers with lower wages and benefits, third-party employer workers, temporary workers, long-term temporary workers, temporary flex workers, and contractors. The GM Lake Orion plant assembles the Chevrolet Sonic, a small car that is designed in South Korea. Most of the Sonic is built in South Korea, packed into containers as “car kits,” and shipped to the Lake Orion plant where it is assembled by a variety of multi-tier workers.40 Lake Orion Assembly was a jointly conceived laboratory for GM’s factory of the future.

The portrayal of jointness as a mutually beneficial strategy belies the outcome of thirty-seven years of the US Big Three-UAW partnership. Jointness did nothing to prevent a 75 percent reduction of UAW-represented workers and the reversal of most of the bargaining gains from the Walter Reuther era. The rebranding of joint programs from Quality of Work Life to Quality Network or from Quality Network to Global Manufacturing System (GMS) did not alter the fact there were over 440,000 workers at GM before the UAW partnered with the carmaker and approximately 50,000 GM remain today. The deception of UAW Inc. was well-illustrated when GM reported $10.8-billion in US profits in 2018 but announced the shutting down of five North American factories – four in the United States, including the historic Lordstown assembly complex.41

The joint training centers were fertile ground for corruption because of the lack of accountability for the hundreds of millions of dollars that flowed from the Big Three through the training centers to the UAW. The theft of $4.5-million from the NTC almost seems charming when compared to the potential for corruption presented by the $61-billion UAW Retiree Medical Benefits Trust. Between 2009 and 2017 functional expenses in excess of $200-million annually for the trust have been reported to the IRS under the category of “other.” The Medical Trust headquarters occupy the entire top floor UAW-GM Center for Human Resources building in Detroit. General Holiefield, Norwood Jewell, and other UAW officials implicated in the training funds scandal are current or former directors of the training centers and the medical trust administrative committee.42

Reforming the UAW from within is doubtful because the rank-and-file have neither power nor status to overcome the mainstream political machine. A grassroots movement is technically possible within the rules of the UAW Constitution, but the international union’s handling of the RUMs and NDM, demonstrates that the Administration Caucus will do anything to crush opposition. As the federal investigation into the training centers ensnares more UAW officials reform could be imposed on the union by the federal government as it did with the Teamsters. Unfortunately, it’s unlikely the interests of workers would be served better by government administrators than the Administration Caucus or the labor-management cooperation schemes of UAW Inc. Organizing a new labor union may be the only solution. •

This article first published on the MR Online website.

Endnotes

- Walter Reuther, Solidarity Magazine, March-April 2014, p. 2.

- Tresa Baldas, Brent Snavely, “Fed: Fiat Chrysler VP Bribed UAW Execs ‘to take company-friendly positions,” The Detroit Free Press, August 19, 2017. The Detroit News, December 18, 2018. Dennis Williams Letter, July 26, 2017. 17-CR-20406, United States of America v. Alphons Iacobelli, Monica Morgan, July 26, 2017. 17-CR-20406, United States of America V. D-6 Nancy A. Johnson, United States District Court, Eastern District of Michigan, Southern Division, Plea Agreement, July 23, 2018. 19-CR-20146 United States of America V. D-1 Norwood Jewell, United States District Court, Eastern District of Michigan, Southern Division, Plea Agreement, April 2, 2019.

- Tresa Baldas, Ex-UAW VP Norwood Jewell Pleads Guilty in Training Center Scandal, The Detroit Free Press, April 3, 2019. Daniel Howes, Robert Snell, and Ian Thibodeau, “FBI’s Training Center Probe Widens to GM, Ford,” The Detroit News, November 2, 2017.Robert Snell “Ex-UAW Boss Dennis Williams OK’d Using Training Center Funds Aid Says,” The Detroit News, July 26, 2018. Robert Snell, “FCA Training Funds used for UAW Executives Pricey 2014 Party,” The Detroit News, February 1, 2018. Robert Snell, “Disgraced UAW Boss’ Life of Luxury Revealed Ahead of Sentencing,” The Detroit News, July 30, 2019.Robert Snell, “Feds Signal UAW Probe Not Done as Jewell Sent to Prison,” The Detroit News, August 5, 2019.17-CR-20406, United States of America v. Alphons Iacobelli, Plea Agreement, December 15, 2017.17-CR-20406, United States of America v. D-7 Michael Brown, Plea Agreement, March 22, 2018. Form LM-2, Labor Organization Annual Report, Department of Labor, Auto Workers AFL-CIO, 2018.

- Kalea Hall, Breana Noble, and Robert Snell, “Feds Charge ex-UAW Leader in Growing Corruption Scandal,” The Detroit News, August 14, 2019. Joseph Szczesny, “Union Training Fund Investigation Examining GM-UAW Fund Query Focusing on Aid to Former GM Department Leader Cindy Estrada,” The Detroit Bureau: Voice of the Automotive World, August 15, 2019.

- Thomas Adams, “UAW Incorporated: The Triumph of Capital,” PhD Dissertation, Michigan State University 2010, p. 369-370. Jennifer Dixon, “A Shroud of Secrecy Surrounds Joint Funds,” Detroit Free Press, May 18, 2001. UAW-GM People, UAW-GM Center for Human Resources, Millennium Issue, Winter 2001. Form LM-2, Labor Organization Annual Report, Department of Labor, Auto Workers AFL-CIO, 2005-2018.

- Special Convention Proceedings, International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace, and Agricultural Implement Workers of America, UAW, Cobo Hall, Detroit MI, March 28-30, 1999, p. 223-224.

- GM-UAW National Agreement, Document No. 46, “Joint Program Representatives,” September 17, 1990, p. 433-437.

- Collective Bargaining Gains by Date of Settlement: UAW-General Motors 1937-1982, May 29, 1948-May 29, 1950, p. 5-6.

- Constitution of the International Union, UAW adopted at Las Vegas, Nevada June 1998, Article 2, “Objects,” Section 1, p. 5. GM-UAW National Agreement, March 21, 1982, p. 279-288.

- Thomas Adams, “UAW Incorporated: The Triumph of Capital,” PhD Dissertation, Michigan State University 2010, p. 325, 569-570. Annual General Motors Employment Level of GM-UAW Represented Employees, GM Market Share and Vehicle Sales, UAW Research Department, 2009. Quality Network, Overview of the UAW-GM Quality Network Action Strategies Work- Shop Participant Manual, June 2003, p. 3-9.

- Amy M Loasching, Executive Assistant to the Secretary-Treasurer Dennis Williams, International Union, UAW to Thomas F Adams, April 2, 2014. International UAW Region 9 New York Training Initiative, IRS-Form 990, 2010 to 2013. Tom Campbell, “Did You Know the UAW Represents Ice Cream Workers at Perry’s in the Erie County Village of Akron?” WNYLaborToday.com.

- Gary Brandt, International Representative Region 2, UAW (Cleveland, OH) v. International Union, The Public Review Board, International Union, UAW, 787-II, (Decision on Reconsideration, April 22, 1988), p. 6. Robert Michels, Political Parties: A Sociological Study of the Oligarchical Tendencies of Modern Democracy. (New York, NY: The Free Press, 1962), p.160.

- Manning Marable, Raced, Reform, and Rebellion: The Second Reconstruction in Black of America, 1945-1990, (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1991), p. 116-119. Heather Ann Thompson, “Auto Workers, Dissent, and the UAW: Detroit and Lordstown,” Robert Asher and Ronald Edsforth, Autowork, (New York: State University of New York Press, 1995), p.188-195.

- Jerry M. Flint, “Automakers Face Blue-collar Blues,” New York Times, January 7, 1973. Heather Ann Thompson, “Auto Workers, Dissent, and the UAW: Detroit and Lordstown,” in Robert Asher and Ronald Edsforth, editors, Autowork, (New York: State University of New York Press, 1995), p. 200-203. Unauthored, “Labor: Sabotage at Lordstown?” Time, February 7, 1972.

- Henry Weinstein, “A Less Perfect Union,” Mother Jones, April 1988.

- Thomas Adams, “UAW Incorporated: The Triumph of Capital,” PhD Dissertation, Michigan State University 2010, p. 60, 223. Ronald Reagan to Robert E. Poli, President, Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization, October 20, 1980, Reagan sent the thank you letter to Poli for PATCO’s support of his campaign for president.

- Barry Bluestone and Irving Bluestone, Negotiating the Future: A Labor Perspective on American Business, (New York: Basic Books 1992), p. 61, 66, 72-73. Albert Lee, Call Me Roger, (New York: Contemporary Books, 1988), p. 17.

- Barry Bluestone and Bennett Harrison, The Deindustrialization of America: Plant Closings, Community Abandonment and the Dismantling of Basic Industry, (New York: Basic Books, 1982), 36.

- Bruce Kauffman and George Martinez-Vasquez, “Voting for Wage concessions: The Case of the 1982 GM-UAW Negotiations,” Industrial Labor Relations Review, Vol. 41, No.2 (Jan. 1988), p.185. Associated Press, “GM Workers Ratify Concessions Pact by Narrow Margin,” Boston Globe, 9 April 1982. “UAW-GM Report,” Special Edition, March 1982, p.10.

- Patrick Hyde, Policy and Law Adviser, Office of Labor-Management Standards, U.S Department of Labor, Position Paper Outline: UAW Joint Funds Are Not a “Labor-management Committee” Under 29 USC 186(c)(9) But Are, Rather, Labor Trusts Mandated to Make Audits Available for Inspection Pursuant to 29u.S.C. § 186(c)(5)(B), Presented to the Office of the Solicitor General in 2004.

- GM-UAW National Agreement, June 24, 1940, Recognition, Paragraph 3(c), p. 6. GM-UAW National Agreement, March 21, 1982, p. 277-278. UAW-GM Report Special Edition, March1982, P. 3, 8, 10.

- GM-UAW National Agreement, Document No. 46, “Joint Program Representatives,” September 17, 1990, p. 433-437.

- “New UAW-GM Human Resource Center Begins with a Bang”, UAW-GM Report: Quarterly Newsletter, Spring 1985, p. 1. Michigan Department of Commerce Corporations and Securities Bureau, Certificate of Amendment to the Articles of Incorporation, “The name of the Corp. is UAW-GM Human Resource Center,” CIN no. 895-076, October 10, 1985. UAW-GM People, UAW-GM Center for Human Resources, Millennium Issue, Winter 2001, p 6. Michigan Department of Commerce-Corporation and Securities Bureau, Certificate of Correction to the Articles of Incorporation, UAW-GM Human Resource Center Corporation Identification Number: 730-390, March 3, 1995.

- Alfred S. Warren, VP Chief Labor Negotiator, General Motors, Actions to Influence the Outcome of Bargaining: Presentation to Personnel Directors, 1984 Negotiations Objectives, Objective I, (11 October 1983), p. C-8.

- Alfred S. Warren, VP Chief Labor Negotiator, General Motors, Actions to Influence the Outcome of Bargaining: Presentation to Personnel Directors, 1984 Negotiations Objectives, (11 October 1983), p. C-8 to C-12.

- GM-UAW National Agreement, October 8, 1987, the “Toledo Accord” printed on the inside of back cover.

- Helen Fogel, “UAW Says GM Plants Abused Fund: some managers used laid off workers collecting jobs bank money to reduce payrolls,” The Detroit News, November 12, 1992. The Associated Press, “Jobs Bank Dollars Misspent, UAW Says,” The Flint Journal, November 12, 1992.

- Jennifer Dixon, “A Shroud of Secrecy Surrounds Joint Funds,” Detroit Free Press, May 18, 2001. UAW-GM People, UAW-GM Center for Human Resources, Millennium Issue, Winter 2001.

- Annual General Motors Employment Level of GM-UAW Represented Employees, GM Market Share and Vehicle Sales, UAW Research Department, 2009.

- GM-UAW National Agreement, November 19, 1973, Quality of Work Life-National Committee, Document no. 81, p. 283-285.

- “Buick 599 Benefit Workers from Quality of Work Life,”Headlight, October 21, 1981, p.1. John Cunniff, “Is Teamwork Concept Just Hot Air?” The Wall Street Journal, October 9, 1991. Ronald Edsforth, Class Conflict and Cultural Consensus: The Making of a Mass Consumer Society in Flint, Michigan (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1987), p. 227.

- Ruth Milkman, Farewell to Factory: Auto Workers in the Late Twentieth Century, (Berkley, University of California Press 1997), 84. Kim Moody, An Injury to All: The Decline of American Unionism, (New York, Verso 1992), 176, 319. William Serrin, “Labor’s New Militants Are Getting More Pushy” New York Times, December 31, 1986. Robert Weissman, “New Directions for the UAW: An Interview with Jerry Tucker,” Multinational Monitor, January/February 1990, p. 27. Bob White,Hard Bargains: My Life on the Line, (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1987), p.13-15.

- David Yettaw Interview 5-28-1998.

- Warren Mayes, “500 in UAW Vow to Fight for More Militant Union,” The Detroit News, 23 October 1989. Peter Downs, “UAW Dissidents Form Party,” Metro Times 8-14 1989. Phillip Dine, “500 Workers Vote to Set up Group for Tougher UAW,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 22 October 1989. Phillip Dine, “Area Man Leads UAW Dissidents,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 23 October 1989.

- Kathy Dahlstrom, “Reuther Raps Region 1C Director at Labor Forum,” The Flint Journal, April 23, 1988.

- Leonard Woodcock and Douglas Fraser and Ken Bannon and Pat Greathouse and Irving Bluestone to UAW Membership, February 1989.

- David Yettaw Interview 5-28-1998.

- UAW-GM Report, September 2007.

- UAW General Motors Modifications to 2007 Agreement and Addendum to VEBA Agreement, May 2009. Form LM-2, Labor Organization Annual Report, Department of Labor, Auto Workers AFL-CIO, 2009-2018.

- Tom Hopp Interview, August 22, 2012.

- Nathan Bomey, “GM Poised to Close Plants in Michigan, Ohio, Maryland, Will Cut 15% of Salaried Workers,”USA TODAY, November 26, 2018. Jamie L. LaReau, “GM’s Secret Plan to Shut Plants, Cut Jobs Likely Signals More to Come,” The Detroit Free Press, November 28, 2018. Sean Szymkowski, “GM Reports Lower 2018 Profits, UAW Workers to Receive $10,750 Profit-Sharing Checks,” GM Authority, February 6, 2019. UAW-GM Contract Summary: Hourly Workers, October 2015.

- IRS form 2848, Power of Attorney and Declaration of Representative, June 2, 2008. IRS form 990, Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax, “UAW Retiree Medical Benefits Trust,” 2009-2017. IRS form 990, 2017 Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax, “UAW Retiree Medical Benefits Trust,” November 14, 2018.