European Progressive Future? Neither Yesterday’s Tsipras nor Today’s Greens

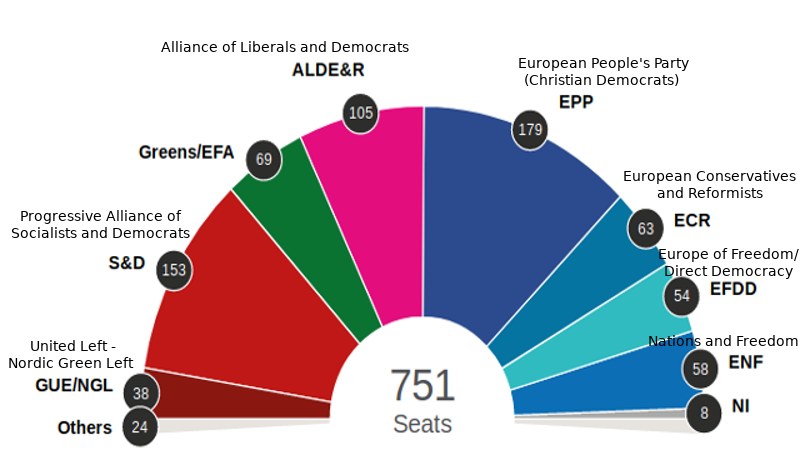

One cannot and should not turn away from the disastrous results of the recent European Parliament elections, especially considering that Leftist parties across the European Union (EU) expected to gain 38 Members of the European Parliament (MEP), achieving around 5% of the vote. The leadership and organizers of European Left needs to think thoroughly over its failure to mobilize and address working people. Even if failure is specific to the concrete context we can abstract a few very important reasons for such weak results.

Lack of a Cohesive Radical Vision Across Borders:

“Just a bit more social.”

Firstly, and most obviously, there is an absence of an integral European program for radical social change that combines viable short-term reformist policies with a utopian transformative vision of the future. The Yanis Varoufakis DiEM25 movement attempted to make one step in this direction, but fell behind two steps in its too reformist demands and a weak organizational support. Even if a few parties on the Left openly promote ecosocialism – one has difficulty understanding why this is not on the agenda of a majority of those parties – most parties find themselves in the trenches defending against the ongoing assault of neoliberal capitalism.

In short, the message of the Left has been boiled down to a mere defence of just a bit more open and a bit more social Europe. There is no radical criticism of the Eurozone and the asymmetrical relationship between the core and the periphery, and there is no call for or practice of international solidarity of working people across all the regions. The absence of a more integral and transformative program that would also be politically effective is coupled by limited media channels, and at times, out-dated use of that media, which restricts the ability to mobilize voters European-wide. Browsing through some slogans and banners in the country I live in, Germany, one perceives very minimal differentiation between the Left and the Social Democrats when they both hold the banner “Für soziale Europa” (For social Europe) – which is an inadequate and too moderate slogan. For an ordinary voter the Left has become just a somewhat better version of what Social Democrats used to be, which is treated as old fashioned in the mainstream parties’ discourse. The electoral campaign for EU elections reflected this: no enthusiasm, no provocation, no sparkle to inspire the desire/dream/community of people. It seems that the goal of European Left is a vote horizon of 5-10% of the electorate rather a radical transformation of Europe.

Secondly, despite some good work on the ground – for example, many members of the Left party (Linke) in Germany have been very active on anti-fascist (anti-AfD) issues, in the environmental movement connected to Fridays for Future and in the movement against rising rents that calls for expropriation of major real estate – the political enthusiasm for the alternative future has been increasingly associated and channelled to the Greens. The climate issue, at least at the present time, overdetermines other social issues, and functions as a fear of climate change (nature) that is juxtaposed with anti-social fears promoted by AfD (fear of foreigners, Islamophobia, Anti-Semitism).

Secondly, despite some good work on the ground – for example, many members of the Left party (Linke) in Germany have been very active on anti-fascist (anti-AfD) issues, in the environmental movement connected to Fridays for Future and in the movement against rising rents that calls for expropriation of major real estate – the political enthusiasm for the alternative future has been increasingly associated and channelled to the Greens. The climate issue, at least at the present time, overdetermines other social issues, and functions as a fear of climate change (nature) that is juxtaposed with anti-social fears promoted by AfD (fear of foreigners, Islamophobia, Anti-Semitism).

Divisions Among the Left and the Failure of Tsipras

Thirdly, the European Union elections clearly testify to further splits on the Left: for example, between autonomous campaigns on a national scale and the Yanis Varoufakis led DiEM project for democratizing the EU; or between movements and citizens’/city initiatives and entrenched, parliamentary-centred Left parties. The spectre of a future in Europe dealing with splits over the legacy of the failed Grexit and lurking Brexit weigh heavily in the discussions on the Left and have substantially weakened its thinking of different, non-capitalist future.

Fourthly, and most symptomatically, the current Left has not yet come to terms with the defeat of the once-messianic figure of Alexis Tsipras. If the sequence of 2014/15 promised an open confrontation with the Troika (the European Central Bank, European Commission, International Monetary Fund), that was catalysed by the OXI referendum in Greece, the social movements, the strikes and the electoral victory of Syriza, the latter has largely neutralized its social base and transformed the Left party into a dull disciple that conducts what the master of austerity says. Despite the IMF openly admitting the failures and injustices connected to the assault on the Greek economy and welfare, the austerity measures penetrate into the deepest pores of society, bringing together a wave of resignation, resentment and internalization/normalization of the crisis. The traumatic conversion from left hero to neoliberal Tsipras has had deep consequences for the Left and points to the weakness of the leadership of Syriza and the uncompromising stance of the EU ruling class, as well as extremely feeble international solidarity in the historic moment. The latest election results in Greece returned the conservative New Democracy party to a powerful position in governing and are thus not at all surprising.

Low Voter Turn-out and the Rise of the Right

Fifthly, even if the reasons for the decline of the Left are dependent on the specific circumstances of each region/country, I should mention that throughout the periphery there has been, as always, low voter turnouts. For example, in my home country of Slovenia, only 28% of people voted. Rather than speaking about lazy and passive voters, I would argue that their choice not to vote is a clear political choice. Many voters do not see any possibility for real change: how on earth should eight MEPs in a 751-member Parliament, only 1% of all the MEPs, exert any kind of influence? If those eight MEPs are so powerless, and everything is decided by lobbies, and in times of crisis, by the Troika, then it becomes extremely difficult to mobilize voters. Also, let’s remember that the Left was beaten not only on the periphery but also in the central countries. In Germany, Linke scored only 5%, while in France, La France Insoumise achieved only 6.5% (Melenchon). Specific to Linke’s decline in support is clearly its plummeting numbers in the East, which is connected to the rise of AfD, the fall of Sahra Wagenknecht within Linke and also the failure to address the issue of the core-periphery within Germany itself.

If the Left lost dramatically, the far Right, in contrast, has been profiting from the disenchantment of voters with the ‘extreme centre’ parties, by the failure of left anti-austerity policies and the defeat of Tsipras, the growing militarization of our societies and the fear of being left behind and losing even more of an already low level of prosperity. The far Right has pioneered a very aggressive use of social media – aided by mainstream media playing along with the game of spectacularizing the far Right – that spread hate speech (Islamophobia) and scapegoat migrants and refugees. This xenophobia has been repeatedly identified by CSU interior minister Horst Seehofer: Migration is mother of all problems. It is no surprise that the xenophobic attitudes and the defence of national workers have been present in other parties, including those on the left spectrum. What is more surprising is that there has been no political will to address the causes of the far Right’s ascendance, especially the brutality of neoliberal austerity that was all along unchallenged by the ‘extreme centre’ parties.

In terms of concrete results, two major far-right-wing groups in the European Parliament will now have around 112 MEPs (EFD + ENF more than 15% of the vote). This makes them three times more powerful than the Left, and also, in fact, on the way to becoming the third largest party. Even more worrisome is the trend toward increasing strength of the far Right in the core countries. Let us not forget that they won in major countries: in the UK – Farage’s Brexit party, in France – the National Front of Le Pen and in Italy – Salvini’s Liga Nord. The far-Right parties in the European Parliament are still quite small, but they have made major gains in the last five years while also succeeding in shifting discourse – forcing their agenda within the extreme centre – which is reflected in a tough anti-migrant stance and support of the ‘war against terror’. The far Right is now organized in the streets and in the parliaments, nationally and EU-wide, and poses a major threat to the future.

Green Parties and their Ethical-Management Lifestyle

Let me now turn to what was, for many, the surprise story of the elections: the rising tide of Green parties. They brought in 69 MEPs, which is a bit more than 9% of the electoral body. In Germany, they won more than 20% of the seats, the second largest number, and in France, with 13%, they are now the third largest party. Let me posit a disclaimer and say I am happy for Green Party comrades, activists and sympathisers for their strong results across Europe and in Germany. To think and act on the viable alternative against neoliberal destructionist capitalism can be built only through ecological socialism. What I would like to, nevertheless, argue here is that one major danger can be seen on the horizon of the apocalypse and environmental catastrophe, the thought of which can elicit only nausea and a sense of helplessness.

The Green Party and those that think and act green have been successful in their branding of an alternative life style. To simplify, this primarily individualistic life style oscillates between smart consumerism – it is your choice to live more ecologically – and self-righteous moralization of politics that demands a deeper change in our lives. The latter often feels like a new secularized religion, which insists on a micro-approach to address and finally ‘resolve’ our bad conscience. A notion of a pure green life is presented as the utopian future. Simultaneously, this utopian vision has already been worked on and realised by a whole army of smart green corporations, using green energy and infrastructure to offer us the option to go to bio-shops instead of big supermarkets and to support local farmers and cooperatives, and drive only electric cars. One comes across very diversified styles of green management of our moral guilt. The more the climate crisis becomes a reality – weather changes, lack of resources, climate migrants – the more strongly people feel called upon to understand what is happening and organize themselves.

Green Just Means “a bit better and a bit cleaner” (technology)

By now, many are very aware that human activity and the capitalist mode of production and consumption are the cause of these major climate changes. If we add that the large majority of extractive and exploitative corporations are located in the West and are responsible for pollution worldwide, we can expect to accumulate an even greater sense of guilt. In this context, the top priority becomes the desire to make at least some small changes in our micro everyday life and follow moral imperatives that help to improve and make our environment a bit cleaner. The formula for Green success then falls from the melting ice and sky. If going to a bio-shop simply means buying a commodity on the (economic) market and feeling good by buying and consuming it, then voting for the Greens performs the same function in the political market. I buy and vote to feel a bit better and believe I, individually, can make a small difference. Voting Green is thus a moral supplement to economic consumerism for concerned and more wealthy citizens who are here not concerned about migration, but, rather, worried about their general helplessness in the face of the apocalypse.

What is, furthermore, very disturbing is when green moral righteousness becomes linked to the new messiah, as if the Green Party can somehow miraculously, along with our individual green choices, save us all from the capitalist path to social and ecological disaster. Given that the major representatives of the established Green Parties call for merely soft reformism and more green capitalism, this messianic expectation is very naïve. In fact, what we need are changes that are radical and more than superficial. Even if an ever-increasing number of individuals are organized ‘bio’ cleaner activities, this is still a small and atomised bubble within the larger frame of capitalism. When one hears that better and cleaner technology can save the planet, one wonders if we have learned anything from the ‘productivism’ of the 20th century. The belief that micro change and green capitalism shall save us is part of a dangerous illusion that can, at best, only stall the climate crisis. Those that vote now for Greens and hope that Green program and leadership can execute transformative changes will be as disappointed as all the Left voters across Europe who saw Tsipras as a champion of anti-austerity and the rising tide of the Left’s answer to neoliberalism. Many of the young voters might also be oblivious to the fact that more than a decade ago, in Germany, the Greens were a part of the most neoliberal achievements in recent German history under the rule of SPD’s Schröder; this government was neither particularly environmentally friendly, nor was it particularly peaceful, for the first time since WWII Schröder sent German troops outside of Germany in order to intervene in the Balkans.

Is There Any Hope for a Radical Utopian Vision?

Might the new Green tide enjoy the temptation to rule in coalition with the ruling extreme centre parties, or might it – by an increasingly radicalized movement and Fridays for Future – turn toward the Left? The future is unwritten, but what is clear at the moment is that in the European Union not much will change. Most likely, the neoliberal party ALDE, which won some 14% of votes, will join those that have run the show for a long time: EPP (conservatives, 24%) and S&D social democrats (19%). The people – with a voter turnout of only around 50% – gave a clear mandate to continue the trend of neoliberal austerity, anti-immigrant wall building and cemeteries in the Mediterranean sea, and further destruction of the environment by adjusting to corporative/capital’s interests.

Future progressive strategy demands not only that we give up the naïve expectation that green technology, micro changes and the Green tide can prevent climate catastrophe without radically intervening or breaking with capitalism. Progressive strategy should also give up on the unspoken ‘productivism’ (of endless economic growth) of the majority of the Left and its weakening defence of the already weakened welfare state. Both Green and Left entertain an array of contradictory positions about downplaying the capitalist growth as if it can be reformed and channeled into a bit cleaner technology and better wage relations? What one could, nevertheless, hope for is that the activism of Fridays for Future will spread from children to parents, from the ecologically engaged to other social sectors, from Friday to Thursday, and so on.

The call for a global climate strike has already been made for this autumn; will that be the first truly global strike? What is certain, however, is that only through the radicalization of leaderships of the Left, the Greens, and the trade unions can we strive for a viable future again, and with it, for a much different world that is not indebted, sold, consumed, and predicated on (capitalist) growth. To do that we need to think and act beyond the limits of welfare and green capitalism distilled in a Green New Deal. It is a good departing point for rethinking and organizing internationally, but should not become a biblical story, we should beware it becomes successful in merely regulating neoliberal beastiality, and in this way, even save capitalism. However, it might not be enough to save humanity, not to mention major portions of animal and plant species. If the Greens and the Left do not push for a radical utopian vision that goes beyond capitalism, the radical Left and Green parties will remain at the margin – dominated by the extreme centre and attacked by extreme right in crisis – and content with 15% of the electoral body and ineffective in determining the future. Their future might look grim, our future can start again, every Friday. •