Rethinking Ottawa’s Transit System

A bold proposal for free transit in a city designed for cars

During the week of February 4-10, Free Transit Ottawa challenged Ottawa’s City Councillors and Mayor to take the Transit Week Challenge. The idea was simple: To get the people who make decisions about public transit to experience the system firsthand. To the surprise of the organizers, the majority of Council chose to participate. Some, such as Shawn Menard, Laura Dudas, and Theresa Kavanagh, enthusiastically took the challenge.

Allan Hubley and Jean Cloutier, Chair and Vice Chair of the Transit Committee respectively, were initially unresponsive but eventually succumbed to the public pressure demanding that they take part. Others, such as Mayor Jim Watson and Barrhaven Councillor Jan Harder, turned the challenge down, citing their busy schedules as prohibiting them from taking transit during the week.

Allan Hubley and Jean Cloutier, Chair and Vice Chair of the Transit Committee respectively, were initially unresponsive but eventually succumbed to the public pressure demanding that they take part. Others, such as Mayor Jim Watson and Barrhaven Councillor Jan Harder, turned the challenge down, citing their busy schedules as prohibiting them from taking transit during the week.

Service Issues

Throughout the week many of the councillors took to Twitter to document their commutes and reported experiences all too familiar to regular transit riders. Buses were frequently late, cancelled, or didn’t stop because they were too full. Stops were icy and some trips were exponentially slower by transit. Overall they encountered a transit system that is unreliable, inconvenient, and not expansive enough to reach many communities within the city.

Currently, the transit system is designed to get commuters back and forth between home and downtown – and even this is done poorly. For people living on low incomes, doing shift work, commuting between suburbs, or trying to access services and shopping during off-peak hours, the system is nearly unworkable.

The city may be able to rationalize its current approach to transit because, despite population growth, ridership has declined in recent years. However, it is difficult to blame citizens for avoiding a system that is becoming increasingly expensive while not serving their needs.

Affordability

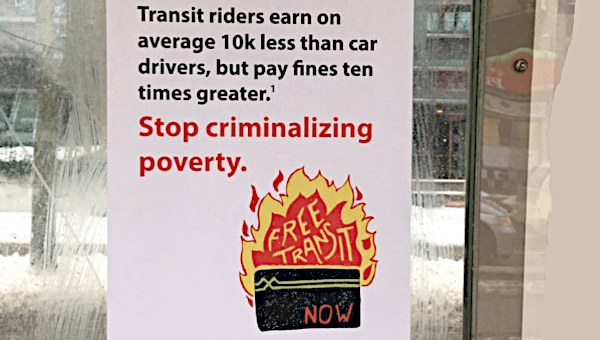

Despite being organized by Free Transit Ottawa, the issue of affordability rarely surfaced in the councillor’s comments during the Transit Week Challenge. This is not entirely surprising – Ottawa city councillors make over $90,000 annually and transit fares would be a nominal expense for them. While affordability was not one of the barriers faced by city councillors using transit, it is a problem for many people living on a low income.

Under the current model, 43% of Ottawa-Carleton Transportation Commission’s (OC Transpo) funding comes from passenger and ‘other’ revenue, with the remainder being covered by municipal contributions and gas tax funding. This heavy reliance on fare revenue presents a greater burden on people with low incomes, since the fare constitutes a higher percentage of their income.

OC Transpo fares have been increasing by 2.5% on average per year since 2011, which is significantly higher than the inflation rate of 1.6%. This also gives us some of the highest fares in the country.

Council plans to raise fares again in 2019 for all users, including for the Equipass program which offers approximately half price transit fares for citizens who have a net income below $20,998 and who are not receiving Ontario Disability Support or transportation benefits from Social Services.

OC Transpo estimates that a mere 8,800 people in Ottawa are eligible for the Equipass, yet few of them are taking advantage of it. In 2017 just 2,600 passes were sold each month. This is probably because of the onerous application process. It requires applicants to provide information regarding the income of all individuals in their household, to submit forms in person or by mail, to wait up to 30-days to receive approval, followed by another in-person visit to receive a Presto card.

So while the Equipass might provide a welcome discount for a narrowly-defined group of people living on a low income in the city, the low uptake of the pass (and high costs of administering the program) suggests that it is inadequate for addressing the transit needs of low income communities in Ottawa.

These issues also raise a broader question – why should anyone living in Ottawa have to pay a fare to use transit?

Transit as a Public Service

There are over 100 municipalities worldwide in which transit is free, with notable examples including Dunkirk, France and Tallinn, Estonia. In addition to being an egalitarian social policy, making transit free to users has the potential to dramatically increase ridership and thereby help to reduce carbon emissions, air pollution, and congestion in the city.

Free transit movements are gaining traction in both Ottawa and Toronto, largely because they have the potential to address both social inequality and environmental sustainability.

Recent reports that indicate we have a closing 12-year window to significantly reduce carbon emissions in order to prevent disastrous climate breakdown.

Free transit is a policy that, unlike market-based solutions such as carbon pricing, can help to reduce carbon emissions without placing additional burdens on working people. In other words, introducing free transit is an effective way for cities to address climate change while also improving life for citizens, especially those living on low incomes.

Free Transit Challenges

The movement for free transit in Ottawa faces a number of challenges and limitations. Eliminating fares within the current system would benefit low-income transit users but it is unlikely to be transformative if the entire system is not improved upon as well. To begin, transit will have to be expanded to accommodate an increase in ridership and to reach neighborhoods with inadequate transit access.

There is a strong cohort of citizens already active in making this happen. In January over 100 people attended a workshop on creating a transit riders organization to give riders a collective voice when it comes to transit issues. At the end of the workshop a committee of more than 25 people from across the city was created with a mandate to organize a founding meeting of a city-wide transit riders organization, tentatively called the ‘Ottawa Transit Riders.’

If this movement gains traction, it could put transit riders in a better position to advocate for reforms to the system. However, it will have to build a large base of support if it hopes to challenge city council’s decisions around transit.

Eliminating fares would mean transforming how transportation is funded. Two creative ways to subsidize the system would be to increase the price of parking and introduce substantial taxes on transportation network companies (or TNCs), such as Uber and Lyft. In any case, making transit completely free while expanding capacity and service would necessitate radical policy change at the federal and provincial levels as well, to significantly increase the funds devoted to public transit.

Instead of addressing the declining ridership, and difficulties transit-dependent people face in Ottawa, city council appears to be continuing its trajectory of prioritizing car drivers. This is evidenced by the fact that while transit fares are raised continually, parking rates have remained frozen over the past decade, and the city continues to actively expand roads and highways.

Groups like Ottawa Transit Riders and Free Transit Ottawa are a promising development, since they’re advocating for immediate reforms and starting conversations about the prospect of free transit. To truly succeed, this movement will require mass uptake to overcome the stasis of our current system and pressure policymakers to transform transit.

We need to work to establish a broad coalition between environmental and social justice advocates and build public support. Daring ideas like free transit are the future; they have mass appeal and need to be actualized. •

This article first published on the Leveller.ca website.