GM Oshawa: Lowered Expectations, Unexplored Opportunities

Following an aggressive public relations campaign in which union officials questioned GM’s loyalty to ‘Canadian taxpayers’, General Motors has apparently agreed to keep its Oshawa facility partially open. No official announcement has yet been made, but there are rumours of a revised plan to retain 600-700 workers by investing $100-million to stamp the cargo beds for pick-up trucks.

There are good reasons to be skeptical about both this rumour and this plan. But even if true, before a desperate workforce reluctantly accepts that ‘some jobs, however few, are better than nothing’, more ambitious thinking should be considered.

There are good reasons to be skeptical about both this rumour and this plan. But even if true, before a desperate workforce reluctantly accepts that ‘some jobs, however few, are better than nothing’, more ambitious thinking should be considered.

The Oshawa facility currently supports 5,700-6,000 jobs: GM directly employs 2,200 hourly workers and some 500 salaried workers, with other companies employing over 3,000 to supply components (some working right inside the Oshawa facility). The new proposal means cutting this total by upwards of 5,000 jobs or 85 per cent.

Thinking Bigger

A little over a generation ago, GM alone employed 23,000 hourly and office workers in the city. The steady decline to GM’s current numbers was accompanied, each step of the way, by the consolation that ‘well, at least some of the jobs remained’. The continuation of that fatalistic and dispiriting response will leave Oshawa – even if the rumours of the stamping plant are correct – at only 3 per cent of the earlier peak.

With this loss of jobs comes a damaging loss of productive capacity – the potential to apply workers’ collective skills to make socially useful products. In the mid-1980s GM Oshawa was the largest auto complex in North America, with three assembly plants turning out some 750,000 vehicles annually while also manufacturing its own axles, batteries, and radiators.

Tony Leah, a maintenance welder in Oshawa, notes that if the rumours of an expanded stamping plant come to pass, the expanded stamping capacity would still occupy only “a tiny piece of the remaining 9-10 million square foot Oshawa complex… all of the assembly process equipment, technology, and space – Body Plant, Chassis Plant, Paint Shop, Supplier Park – [will] remain empty.”

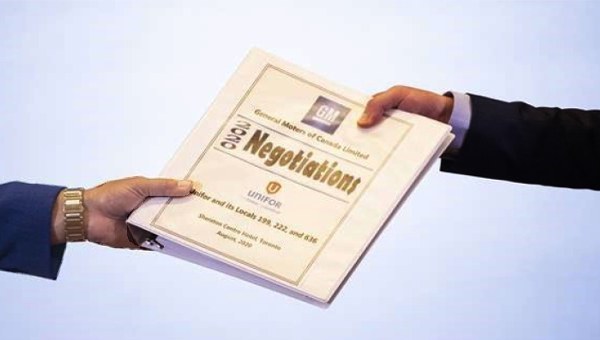

The Unifor leadership deserves credit for pushing GM off its original ‘non-negotiable’ declaration that a complete closure was a done deal. Yet it also shows the limits of its overall strategy. The concessions made during the last round of bargaining were to no avail but contributed to weakening workers’ confidence to resist. The enthusiasm for the security the new trade agreement with the USA and Mexico would bring was badly misplaced. The same goes for a campaign primarily focused on hiring a public relations firm and choosing the main tactic as boycotting GM vehicles from Mexico.

It was of course always a stretch to expect GM to reverse itself on so fundamental a strategic decision as ending vehicle assembly in Oshawa. This might well have been the case even with a massive mobilization of autoworkers and the community. That’s why posing possibilities beyond GM was so critical. The union’s refusal to explore broader opportunities, ones that reached beyond GM, reflected a disheartening failure of imagination, a failure that reinforced a steady lowering of expectations on the part of the union leadership, its members, and the community more generally.

The politicians have been worse. Provincially, the Doug Ford government – fresh from putting up billboards declaring Ontario ‘open for business’ and frantic to get the negative reality of Oshawa out of the spotlight – meekly repeated GM’s mantra of Oshawa being ‘a done deal’. The Federal government, with which the union leadership claimed a special relationship, was only a few rhetorical steps behind in trying to dampen hopes.

Is a stamping plant really the best we can aspire to? After all the lamentations about Canada’s over-dependence on resources, and the recurrent task forces on developing a manufacturing base, how can we let those facilities we already have – like the Oshawa complex – fade away with so little resistance and popular outrage? And more directly: If the stamping plant does materialize, why would we give up on the rest of this massive complex?

A Tale of Conflicting Perspectives

Let’s start with General Motors’ decision to leave. The Oshawa plant is split between cars and trucks. GM has been losing interest in producing cars in Canada and the USA because their profit margins are low. Better, from GM’s perspective, to build those cars – or when the transformation to electric vehicles occurs – in Mexico or China.

As for the highly profitable trucks, GM is trying to sell as many of these as it can before environmental limits put the brakes on such sales. But the model Oshawa got in exchange for concessions was an older one that some had already seen as having only a transitional lifespan of perhaps 18 months until the new models were geared up in other plants. In any case, for GM a half empty plant (i.e. after car production goes) is a liability. More profitable from where the corporation sits is rationalizing capacity across all its operations and reallocating Oshawa’s remaining production elsewhere.

According to business consultants, and readily confirmed by the corporation, the Oshawa facilities regularly ranked at or near the top of all of GM’s operations in terms of productivity and quality. In the end, however, this turned out to not matter all that much. There’s a lesson here of note for workers everywhere: there comes a point when we must think beyond putting all our hopes in private corporations with interests antagonistic to our own.

Where the union disappointed was in refusing to come to grips with the fact that GM was no longer the salvation for working people, and in consequently not exploring – even as a last resort – other options. It rested with GM’s Oshawa retirees to pose the crucial question of a reorientation that went beyond appealing to GM.

The retirees noted the centrality of the accumulated sweat of workers to GM’s accumulated profits. They pointed as well to the mind-numbing $11-billion contribution the Canadian public made to keeping GM alive during the financial crisis. They especially took into consideration GM’s loss of interest in the facility. This led to the straightforward moral and practical conclusion of placing the facility and its equipment in public hands, and the retirees passed a resolution to that effect. The hourly workers followed by passing a similar resolution at a subsequent membership meeting.

This response is to be commended, but those votes involved a small fraction of GM retirees and workers. And though the local leadership did not oppose the resolutions, neither did they give them any profile. No public statements were issued to broadcast the resolutions, and they weren’t even reported on the local’s website. The national union paid zero attention to the resolutions.

The dismissive reaction of the local and national leadership was no doubt made easier by the fact that in itself, ‘nationalization’ alone is not enough of an answer. Though the sentiment broke with the union’s public relations response, enthusiasm is difficult to generate without a plan for what might follow. What needed elaboration was what a nationalized facility like that in Oshawa might actually produce.

What do Canadians need, and do the workers in Oshawa have the capacities and skills to produce such equipment and goods? If not, can those abilities be developed? And what role should all levels of government have in bringing those needs and capacities together?

Imagining a Credible Alternative

If workers came together in a room and brainstormed about what they might produce with some external support, they would likely come up with a significant list, some suggestions being stronger than others. Why not make some of the things we currently import? Why can’t we make some of the products that government and para-government institutions like schools and hospitals purchase? Could, for example, a part of the Oshawa facility make products needed by our aging population – could it make wheel chairs, wheel mobility scooters, disability ramps, home lifts, accessibility beds, oxygen treatment equipment?

The environmental crisis in particular holds out the promise of all kinds of potential jobs. If we are to prevent or at least limit the looming environmental catastrophe, it is clear that everything about how we work, live, travel, and transport goods will have to be transformed. Everything. This ranges across the accelerated production of wind turbines and solar panels; energy saving lighting, heat pumps, small motors and generators for energy transmission; energy efficient doors and windows as well as modified appliances for every home and office; electric cars and electric fleets of utility vehicles.

The last example – fleets of electric utility vehicles – seems the most obvious alternative for an assembly plant. Public vehicles will inevitably have to be electrified or run on renewable energy resources, and this means a growing market for electric post office vans for mail and package delivery (as suggested by the Canadian Union of Postal Workers), hydro vehicles doing maintenance and repair work, minibuses to supplement public transit, the electric scooters mentioned above for seniors and people with disabilities, and electrified vehicles in agriculture, mining, and construction.

With the stamping plant confined to a small part of the plant, the assembly of fleets of electric utility vehicles could occupy the main part of the plant. This might even give the stamping plant additional work making stampings for the fleets. Particularly important, it would mean that the life of the complex would not end if GM suddenly (but not surprisingly) decided that it would rather close the stamping plant and sell the larger facility to developers looking to build condos. If, with the fleet vehicles and the (rumoured) stamping plant excess capacity still remained, the unutilized subsections of the plant could focus on addressing the miscellaneous aging and environmental-related products cited above, or other products workers might come up with.

Much of the needed equipment and skills already exist in the Oshawa plant. The components sector, especially where GM work is being lost, has the ability and flexibility to shift to supporting parts for these vehicles. Further high-tech support could be brought together from the tool and die industry, metal fabricating, aerospace (propulsion systems, materials), the Waterloo computer corridor, and Canada’s experienced engineering and construction firms (all the more so if scandal-ridden SNC-Lavalin were also made into a public enterprise!).

Moreover, an Oshawa complex converted to ‘green production’ and looking to the future might also include hiring hundreds of young engineers working on-site to consider what other needs and capacities might be developed. This would have the added advantage of contributing to building a national planning capacity to convert other threatened closings – of which there will be many – as well as generating new technologies and products which could help alleviate the environmental crisis.

From Ideas to Implementation

The indispensable condition for achieving the conversion of the GM Oshawa plant and keeping the jobs lies with the commitment of the Oshawa workers. No one else is as equipped to lead this fight and place an alternative on the agenda.

Moving to think bigger can be intimidating. But it seems criminal not to at least try and keep Oshawa alive. Furthermore, the history of the past few decades in auto and elsewhere convincingly shows that unless workers take a strong collective decision, things will keep getting worse.

If the workforce does organize itself around an alternative for the GM plant, the next step will be to rally other workers and potential allies. The recent teacher mobilizations in California provide an inspiration and a blueprint for building diversified community coalitions to limit corporate power and win support from the mayor and city council. With such support GM could be blocked from moving its equipment or selling the land (the build-out dates as of now seem to be the last quarter of this year), and the facility could instead be converted to a municipally-owned facility producing socially useful and environmentally-essential products.

This would clearly require substantial support from the provincial and federal governments to have their agencies purchase the Oshawa products and to fast-track the use of electric fleets. Both layers of government would also be critical to providing finance, developing needed skills, supporting a transport redevelopment agency to chart, facilitate, and monitor transport redesign, and developing a planning capacity that can address new closures next time they occur – and there will be no shortage of such ‘next times’ in auto and elsewhere.

Of course, Queen’s Park and Ottawa will not easily jump in. But facing a public campaign, the provincial government may be vulnerable to pressure given its promise of providing new manufacturing jobs and in the face of popular reaction to Ford’s massive cuts in jobs and services in health, education, and public transport. And the federal Liberals – weakened by the SNC-Lavalin scandal and with an election coming up – have offered a lot of rhetoric on both the environment and defending workers but have fallen far short of dramatic action on both counts.

It is unlikely that any such massive project would go forward without a feasibility study to show that all this is not just pie-in-the-sky. The crucial point is that addressing ‘feasibility’ is not a technical issue but a matter of struggling over the most basic principles that should govern our society. It cannot mean asking how much profit the facility would generate in competition with Mexico, China – or the USA and Europe for that matter. We have seen where such criteria take us. Rather, it demands another set of questions:

- What are the wider social benefits of the products being produced (are the products socially useful; do they contribute to addressing the pressing environmental crisis)?

- Can this project provide well-paying jobs with dignity for working people?

- Can the workers involved do the job effectively and at high quality?

- Does the project develop the future capacity of Canada to respond to future economic and social restructuring?

Conclusion

GM was bailed out on the assumption it would return the favour with sustained employment. It’s now the workers’ turn to be supported – in this case, however, with a social plan that benefits the entire community and not just a private corporation that can move on when the wind changes.

But first the Oshawa autoworkers must take a stand. They will need to put their own stamp on the remarkable resistance that has flowered elsewhere. Something historic is happening around the world – sometimes with dark and negative undercurrents, but at its best, inspiring and hopeful. Frustrations are overflowing over the loss of control over daily life, the growing inequalities and shrinking democracy, the perpetual insecurity, and the narrowing of hope across generations.

Fighting back has no guarantees, only possibilities worth considering and trying. Will Oshawa join this world-wide rebellion and find their own constructive way to say a loud ‘No!’ to the unrelenting lowering of expectations followed by a louder ‘Yes!’ to once again raising and creating new possibilities? •