The American Left Resurgent: Prospects and Tensions

The American political system is experiencing a crisis of hegemony. The moderate, bipartisan center that had been the mythical linchpin of American politics during the “long Cold War” is facing the possibility of a terminal decline.1 Donald Trump’s election has put this crisis into stark relief, having turned the Republican Party’s decades long flirtations with white ethnonationalism into an overt endorsement.

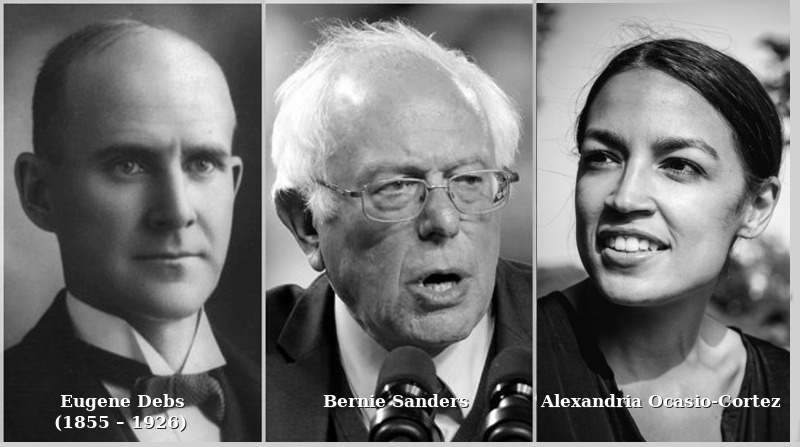

At the same time, the organized left is also resurgent. This revival was first exemplified in Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter, and turned more durable with Bernie Sanders’ insurgent campaign during the 2016 primaries. Sanders’ social democratic message galvanized the Democratic Party’s progressive base, and spurred the rapid growth and the electoral victories of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA). The DSA and other left organizations outside the Democratic Party have achieved the unimaginable by returning “socialism” to the mainstream.

The American left currently finds itself on unfamiliar political terrain. Interest in socialism is growing, especially among a younger generation. Outrage toward Trump’s racism and xenophobia, millennials’ anxieties about their economic prospects, and a deepening skepticism about the ability of establishment to address these problems has caused many to seek answers on the left. The American left hasn’t experienced such a rapid influx of activists and adherents since the 1960s.

Uncertainty and Potential

And yet, this rebirth comes with uncertainty. One of the challenges facing the left since the anti-globalization movement of the late 1990s is producing lasting institutions, and making tangible inroads within working class communities, especially among people of color. Though a diffuse swathe of organizations and groups are cultivating substantial political capital, these forces have yet to cohere into a unified movement or forge durable coalitions. Potential working class constituencies for a left agenda and their institutions – trade unions, churches, and social organizations – remain wedded to the Republican and Democratic parties. Questions about the sources of political power, how to take it, and the very ideological and institutional nature of democratic socialism dog many activists. Moreover, the task of recomposition into a new political force has inflicted the American left with its own internal polarization. It remains a patchwork of different groups split between trying to push the Democratic Party to the left or to carve out an independent space outside the American political duopoly. Though revived, the left has a long uphill battle before it can claim solid support among working class Americans.

The current situation is best understood as a period of ideological and organizational renewal and consolidation. At the same time, within these disparate articulations of the left’s content and form, it is possible to identify certain emerging tendencies and contradictions in its trajectory. Four issues in particular – the meaning and content of “democratic socialism,” the left’s relationship to the Democratic Party, bridging the divide between class and identity along which the left has fragmented since the 1980s, and the tension of organizing via both social movements and elections – are likely to shape its organizing successes in the near future.

The U.S. Left at the Beginning of the 21st Century

The brief surge of the American left in 2011 with Occupy Wall Street (OWS) was a reawakening of political forces sublimated by the War on Terror. The 9/11 terrorist attacks punctured an active and vibrant anti-globalization (or alterna-globalization) movement. After a short period of disorientation, these left forces quickly recalibrated into an antiwar movement in the run up to the Iraq War. Though the Iraq and Afghan wars quickly descended into quagmire, opposition to the American imperial thrust failed to unite the many strands of left tendencies into a coherent opposition.

The 2008 financial crisis offered opportunities for the articulation a new left politics, especially in magnifying the growing class disparities that have defined post-1970s capitalism in the United States. The spontaneous explosion of OWS in September 2011 injected enthusiasm into a mostly dormant protest politics as Occupy camps mushroomed in cities across the United States. Like the antiwar and anti-globalization movements before it, Occupy was an eclectic mix of progressives, socialists, anarchists, and even libertarians. This archipelago of protest activity, centered around the occupation of Zuccotti Park in New York City, though successful in putting forward the slogan “We are the 99%”, failed to resolve all of its ideological and organizational contradictions.

OWS’ emphasis on horizontalism prevented its concretization into lasting institutions once its protest energies were exhausted. In their demand for autonomy and mutuality beyond state institutions, the Occupiers aspired to a society “based on organic, decentralized circuits of exchange and deliberation – on voluntary associations, on local debate, on loose networks of affinity groups.”2 As Jodi Dean has argued, the “individualism of [OWS’] democratic, anarchist, and horizontalist ideological currents undermined the collective power the movement was building.”3

The ephemeral nature of OWS and its organizational form based on the physical occupation of public space made it highly susceptible to police repression. By late fall 2011, Occupy camps were dismantled in a nationally coordinated effort between local police and the Department of Homeland Security. Activists were placed under surveillance and subject to arbitrary arrest. In all, by June 2014, the website OccupyArrests had chronicled 7,775 arrests in 122 American cities.

The American left’s inability to consolidate after the 2008 crisis was due to its uneasy relationship with the Obama administration. Though it quickly revealed itself as Clinton-lite on economics and foreign policy, legislation like the Affordable Care Act, social-cultural victories like same-sex marriage, and the right’s vitriol toward both Obama and his agenda were enough to temper the emergence of a left opposition after the defeat of OWS.

While an active left pushing a more equitable social-economic agenda went dormant after 2012, the racism at the heart of the American carceral state surged to the surface. The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement illuminated not only police extrajudicial killings and the prison industrial complex, but the embedded racism in the American criminal justice system as a whole. The issue of police violence and incarceration, long ignored and even justified by the American media, became a focal point of public discussion. BLM transformed political activism in African-American communities, brought in a new generation of activists, especially black LGBTQ and feminist leaders, and signified the end of the Civil Rights generation’s long dominance over black politics. Uttering “black lives matter” publicly even became a brief litmus test for many mainstream Democratic candidates, a gesture that reinforced the precarity of black bodies versus the privilege of white bodies. Though BLM’s lasting political successes were few and highly localized, its rhetorical intervention returned racism, police violence, and radical prison reform to a central place in any viable agenda for the new American left.

Despite their limitations, Occupy Wall Street and BLM made crucial contributions. First, OWS’ channeling of outrage toward the 1% moved income inequality and class into the American political mainstream. Black Lives Matter underscored the centrality of race to the American class structure by zeroing in on the “whiteness” of that 1% and the institutions of state violence that maintain it. Ultimately, BLM reiterated an age-old left truism: any serious analysis of capitalism must see the liberation of people of color as a condition for the equality of all. Both of these contributions laid the ideological and rhetorical foundations for a social democratic message that took aim at the Democratic Party’s neoliberal turn.

Second, the burning out of OWS and the fading of BLM from the national agenda signaled the shortcomings of horizontalism and activistism that had been hegemonic in the American left since the 1990s. Activists who cut their teeth in OWS learned from its limits and began reevaluating the necessity of institutional engagement, organization building, and the party form as a locus for political activity. Those inside and outside BLM realized that coalition building and the forming of united fronts on the local and national levels with other movements were necessary for substantive radical political change. Both of these became major features of the American left’s flowering in the watershed year of 2016.

The New American Socialism

The return of the “socialism” to American political discourse surprises many. Most liberals and conservatives assumed that socialism as a viable political project disappeared with the collapse of Soviet communism. Yet since the 2008 economic crash, attraction to alternatives to really existing capitalism among the post-Cold War generation has increased. Among self-identified Democrats, positive views of socialism now outpace those of capitalism, 57% to 47%, even as Americans’ views about the two have stayed relatively consistent since 2010. Bernie Sanders’ Presidential campaign, the rapid growth of the DSA, and the election of new figures like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez have revived curiosity in what “democratic socialism” exactly is, and how it differs from “socialism” and even “communism.”

The growing popularity of democratic socialism has placed new pressure on its advocates to provide a clear definition. Part of the confusion comes from Sanders’ own popularization of “democratic socialism.” In a speech in November 2016, Sanders equated “socialism” with Roosevelt’s New Deal, robust labour and environmental regulations, and the welfare state. While no socialist would oppose such measures, many would see Sanders’ notion as rather milquetoast. Judging from debates about “democratic socialism” in the left press, the ideology contains much of what socialists from previous generations have advocated: an end of exploitation and oppression through the radical democratic restructuring of political, economic, and social relations along equitable and cooperative lines.

Notions of what a socialist economy would look like range from a form of mixed economy to one based on cooperatives and workers’ control. Most democratic socialists are skeptical of centralized planning. Many call for a market socialist approach where the nationalization of healthcare, telecommunications, and the financial sector coexists with small, privately-owned businesses and worker-owned cooperatives.4 Like socialists of the past, today’s adherents broadly see the end of all oppressive Isms (sexism, racism, imperialism) as only possible through the radical transformation of the relations of production under capitalism.

If “identity politics” dominated much of the American left since the 1970s, today’s left seeks to reinsert class back into the pantheon of struggle. But rather than being economically determinist, socialist ideology today is an eclectic mix of a variety of Marxist, post-structuralist, and progressive tendencies. While class analysis may provide the primary lens for a socialist analysis, sexual, gendered, racial and other identities and positionalities are seen as adding layers that shape the particularities of a group’s class relationship and struggle.

Within democratic socialism, the modifier “democratic” plays two functions. First, it is an ideological commitment to democracy as a central aspect of any socialist policy, institution, or practice. The insistence on democratic is at once a distancing from and a recognition that the lack of democracy caused the failures and tragedies of communist states in the twentieth century. Rhetorically, it is also a preemptive rebuttal of the dismissals of socialism as a necessarily totalitarian ideology. Following from this, the democratic aspect is a disavowal of the democratic centralism of the Leninist party model, and of insurrection and violence as the primary means for revolutionary change.

Today’s democratic socialists range from gradualists to advocates of immediate sweeping reforms. But all show a willingness to work politically within the confines of liberal democracy, at least temporarily and provisionally, to achieve power. Unlike the communist revolutions of the last century, democratic socialists seek to build a constituency for socialism via a combination of mass movements and the ballot. In this, the strategic orientation of today’s democratic socialists is closer to the Eurocommunist movements of the 1970s than to the Bolsheviks of the early 1900s.

Despite consensus on the broad strokes of democratic socialism, the DSA is a “big tent,” multi-tendency organization. It includes a myriad of left-wing trends, many of which entered the organization during its membership boom in 2016. This has resulted in a fragmented identity within and between local chapters. Moreover, the influx of new members often unfamiliar with the nuances of socialist ideology, terminology, history, and practices add to the challenges of forging a shared organizational identity. This “identity crisis” is most vivid in discussions over the left as a community, its values (ideological, moral, and cultural), and how to regulate them.

Despite consensus on the broad strokes of democratic socialism, the DSA is a “big tent,” multi-tendency organization. It includes a myriad of left-wing trends, many of which entered the organization during its membership boom in 2016. This has resulted in a fragmented identity within and between local chapters. Moreover, the influx of new members often unfamiliar with the nuances of socialist ideology, terminology, history, and practices add to the challenges of forging a shared organizational identity. This “identity crisis” is most vivid in discussions over the left as a community, its values (ideological, moral, and cultural), and how to regulate them.

The left as a community of shared values, ethics, friendship, comradeship, and mutual aid has a long history. Socialist and communist parties were more than just political movements. They were also social and cultural spaces that gathered like-minded people. Crucial to party life was the provision of entertainment, spaces of sociability, and the cultivation of personal relations in addition to politics. However, the history of these organizations also shows that the line between politics and values is porous. Not only do internal alliances intersect with personal relations, but conflicts over values tend to take on political valances. As historians of socialist and communist parties have shown, most party expulsions resulted not from ideological differences, but from personal behaviors deemed in violation of “party ethics.”

The DSA recognizes the importance of community building as an important aspect to political work. “Community building helps sustain us,” reads one chapter organizing document. Members are urged to recruit friends, hold house parties, and, especially for newcomers, speak to their personal socialist conversion experience. The document suggests: “Let people talk about why they are there and tell their personal story,” “how did you become political?” “what does democratic socialism mean to you?” All of this “builds bonds between people.” The importance of a socialist community contains a crucial political thrust: to “counter neoliberal capitalism which divides and isolates us.”5

Yet the left has a poor track record in reconciling its political mission (build a mass base among the working class) with its emphasis on community (providing a social space for its adherents). One of the main hindrances is the left’s historical tendency to slip into puritanism and overly regulate and adjudicate norms. Often, and the DSA has endured many national and local scandals (exacerbated by social media), building a “socialist” community is constituted through the identification, shaming, or expulsion of its transgressors. Given the politically charged atmosphere of the left, these ethical questions are often articulated, judged, and punished in a political and ideological key.6

The contradictions between politics and community have not gone unnoticed. The ethical contours of the “socialist community” has been the subject of debates about the social purpose of organizations like the DSA. In a biting critique, Benjamin Studebaker warned against the left as serving as a site of “spiritual self-actualization.”7 Others have cautioned against members’ tendency to “fixate on the purity and homogeneity of their own in-group and attack other members of DSA for not meeting their standards.”8 Still others point at a penchant toward “rigid radicalism” by reducing “good” politics to an individual’s values, morals, and ethics.9

The question of the socialist community raises other challenges. Building working class power requires facilitating the activism of that class. Yet activism often requires a measure of social and economic privilege. The demands of work, family, and other responsibilities and risks can preclude the involvement of working class members, especially those of color. In these cases, activism tends to fall on the shoulders of a small coterie of members. Often it is privileged minorities that exercise disproportionate power in shaping a community, and substitute informal relations for procedure. Like socialist and communist organizations before them, today’s left runs the risk of cliques and factionalism not necessarily based in ideology (though often expressed in those terms), but forged through informal networks and friendships. Common attempts to remedy the power of informal networks with calls for horizontalism (a flattening of internal hierarchies) or transparency can merely mask the persistence of these relations.

Organizing Beyond Class and Identity

A major effect of the post-2016 period was to relitigate the longstanding debate on the left about class and the politics of identity. On the surface, Sanders’ narrative of the corruption of the “billionaire class” and Clinton’s cynical deployment of the language of intersectionality seemed to neatly capture this division between an Old Left focus on “working class issues” (jobs, social protection) and a post-New Left shoehorning of the language of identity into what Nancy Fraser has called the “progressive neoliberalism” of the Clinton and Obama years.10

Trump’s victory, as well as Sanders’ earlier success in states like Michigan, Wisconsin, and Indiana, prompted many liberal observers to advance a narrative of populism and white working class revenge. Centrists like David Brooks, Mark Lilla, and Francis Fukuyama have blamed the left’s focus on identity politics over the material concerns of average Americans. These readings understand the 2016 election through the lens of anti-elite ressentiment: silent Americans’ embrace of Sanders and Trump are equivalent expressions of populist anti-establishmentarianism.

Still, to read the resurgence of the left strictly as the “materialist” pushback against liberal identity politics cedes far too much ground to the liberal narrative of a clash between class and identity – between material and “post-material” concerns, or between the winners and losers of globalization. Today, the American left is being forged anew through mutually-informing organizing and critique. It is undergoing a complex process of organic reconstitution, in which traces of both the Old and New Lefts exist. Old debates – on nationalism and internationalism, race and political economy, social reproduction and the limits of neoliberal feminism – are being reworked and reframed, now more closely influenced by the immediate pressures of contesting for power than before.

There is a shared understanding that the left must move beyond the neoliberal identity politics of the 1990s and 2000s.11 More controversial is the political subject that should be the main focus of organizing efforts. One fault line has been a distinction between a strategy backing a handful of national campaigns (Medicare for All, a Green New Deal) in coalition with organized labour’s “rank and file,” and one seeking to broaden the sites of struggle to include precarious and undocumented workers, racial minorities (especially in poor urban areas), tenants, students, the LGBT community, and sex workers, among others. The two outlooks agree on the need for building a mass movement and the democratization of existing political and social institutions. Their disagreement is about the locus of the most transformative and radical energy. Namely, who will be the new political subject, what form will it take, and how to balance between a national program and local initiatives?

One point of controversy is whether the socialist left should throw the bulk of its energy and resources into universal, popular demands, such as Medicare for All. Building on Adolph Reed’s critique of liberal identity politics, proponents argue for the creation of a “cohesive block” forged from “shared economic demands based on one’s location in the capitalist class structure.”12 At the core of this approach is an insistence upon the ultimate class character of identity politics, and against the essentialization of the identity-subject position of an oppressed group.13

In contrast, those who stress the unique structure of racial domination and the racialized and gendered nature of all class struggles argue that adhering to a normative concept of class “excludes social relations anchored in rightlessness, wagelessness, and extra-economic coercion, [that obscure] the violence constituting capitalism’s capacity to reproduce itself.”14 Per these accounts, the left cannot neglect the radical origins of identity politics and the multifaceted struggles, demands, and contestatory narratives that they enable.15

“Today’s left faces the challenge of articulating existing grievances into a new political formation.”

These discussions over identity and class have functioned as a proxy for strategic debates, within the DSA and beyond, about the most effective means for a socialist movement to achieve institutional power. If the major problem with liberal identity politics has been its tendency to essentialize subjects and project a specific political affect onto them, today’s left faces the challenge of articulating existing grievances into a new political formation. Rather than the conversion of people to socialism, the left must see politics as the process of forging unity out of plurality. It can do so by advancing concrete measures that speak to popular discontent and draw specific subject positions into a broader coalition of forces.

Should the left hope to overcome the stale debate between the primacy of class or identity, this will involve bridging grassroots mobilizational campaigns, including for racial and criminal justice, climate justice, and a “feminism for the 99%,” with local, city, and state-level electoral efforts that can cement the gains of these localized struggles within public institutions, potentially opening the way for further radical demands.

Between Elections and Movements

The new American socialism is highly aware that the pressing short-term issues that will determine the future of this movement will be fought out on the terrain of the liberal-capitalist state. Today’s socialists are beginning to ask what it would take to govern, and if so, how a political movement can meaningfully engage with the state. These conversations have become more concrete and nuanced, and largely inspired by Marxists like Luxemburg, Gramsci, Miliband, and Poulantzas that sought to move beyond the dichotomy of “reform or revolution.” This revival of state-strategic thinking has attempted to outline a viable path that draws on the best of both electoral and mass movement politics, while acknowledging the productive tension between them.16

Given that the United States’ “first past the post” electoral system incentivizes a two-party arrangement that has historically marginalized socialist and labour parties, the Democratic Party casts a shadow over most of these left strategic and tactical conversations. Historically, the DSA’s political strategy had been pragmatically pushing the Democratic Party to the left, toward what its founder, Michael Harrington, had called “the left-wing of the possible.” Yet today’s DSA is a different organization. The rapid influx of younger members dropped the median age from 68 to 33 in the last five years. Though a national organization, its decentralized structure provides substantial autonomy for local chapters (although not always autonomy within a given chapter) to set their own priorities. Each chapter is, in theory, capable of adopting initiatives that are sensitive to the local correlation of political forces, institutional capacities, and resources for political campaigns.

Two broad political trajectories have formed within the DSA. One prioritizes electoral activism within the Democratic Party around universal social measures such as housing, healthcare, and criminal justice reform. The other focuses on “base-building” and mutual aid by organizing workers, tenants, and students, and stressing autonomist initiatives with the aim of immediately breaking from the Democrats.

A dominant intellectual tendency within Jacobin, with which the DSA is closely linked, advocates “non-reformist reforms” or “revolutionary reforms.” Vivek Chibber has argued for a gradualist approach: a “combination of electoral and mobilizational politics” seeking to eventually build a labour-based party that can both pursue policy reforms and generate power in civil society.17 With the emergence of such a labour-based party unlikely in the short term, the focus has been on actualizing Sanders’ “political revolution” by supporting popular universal measures such as Medicare for All and the more radical gains that this would inspire.18

Responses to this dualist strategy have pointed to the structural limitations set by both state and capital, and the inherent contradictions in a strategy that bridges electoral participation and cultivating social movements. To that extent, critics argue that substantive, base-building socialist reforms cannot be won through the Democratic Party. Attempts to either reform the Democratic Party or compete on its terrain, they posit, is counterproductive. Instead, political energies are best directed at immediately cultivating independent organizations and building a mass socialist party.19

Yet appeals to “base building” within the working class are likely to remain a political slogan without an accurate concept of that class. Apart from the superficial discussions of the “white working class” in relation to Trump, the relative absence of the language of the “working class” in American political discourse compared to the overwhelming appeals to the “middle class” is indicative of this problem. Recent campaigns such as the Fight for $15, the 2018 West Virginia teachers’ strike, numerous graduate student unionization efforts, and the Marriott workers’ strike hint at the reformation and emergence of a more racially diverse and increasingly precarious “new working class,” especially drawn from education, service work, and care work.20 Still, these pockets of organizing have not yet coalesced into a larger movement representing all skilled and unskilled, full-time and itinerant, native and immigrant, and industrial and service workers. Forging a new politics that brings a multifaceted conception of class to the center of working people’s identities and constitutes them as a new political subject will be the crucial test of the left’s success.

The institutional barriers of the American electoral system also present challenges that largely incentivize socialist candidates to run as Democrats. A “first past the post” arrangement discourages the left from splitting the vote. A decentralized voting system encourages state-level voter-suppression schemes, including frequent voter roll purges and strict identification requirements. These, in addition to the anachronistic electoral college, mean that the American system structurally over-represents sparsely populated, conservative, rural areas at the expense of left-leaning urban centers.

Thus far, DSA’s legal status as a political organization rather than as a party has allowed it to instrumentally use the Democratic ballot line to either endorse or run left candidates without the accompanying financial and legal constraints. Seth Ackerman has advocated a popular proposal in favor of a “national political organization that would have chapters at the state and local levels, a binding program, a leadership accountable to its members, and electoral candidates nominated at all levels throughout the country.”21 Yet this proposal has not been officially adopted, and the majority of DSA-endorsed candidates simply run on Democratic Party ballots in a patchwork manner.

The results have been mixed. In the 2018 electoral cycle, DSA-endorsed candidates were elected to state-level offices in Virginia, New York, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Maine, among other states. In addition, Ocasio-Cortez, the face of the new electoral socialism for many, was recently elected to the House of Representatives as the youngest ever woman in Congress. However, a number of other progressive candidates backed by Sanders’ Our Revolution organization lost in red-blue swing states. In the autumn 2018 midterm elections, it was a broader liberal antipathy to Trump, especially in more moderate suburban areas, rather than a thirst for a more social democratic agenda, that motivated the Democratic “Blue Wave.”

The example of Ocasio-Cortez notwithstanding, socialist organizations like the DSA do not currently have the capacity to define or influence either federal-level or gubernatorial elections. Even its ability to influence or win local elections is highly subject to local conditions. Concerns about the cooptation of the DSA by the Democratic Party are thus more indicative of the growing pains over the collective identity of an organization that saw an unexpected, rapid influx of new members. The DSA’s growth over the last two years has largely been via disaffected liberals and progressives. With DSA-backed candidates continuing to run as Democrats, successfully pushing the Democratic Party to the left may encourage the exit of newer members who joined as part of the organization’s post-2016 membership surge. Yet at this moment, the tactical disagreement between working with(in) the Democratic Party and independent base building is a false binary. Both cases overstate the left’s capacities to simply choose one or the other path, rather than its course being largely determined by circumstances not of its own choosing.

The DSA’s self-described character as a “big tent” organization also raises questions about its future direction, especially regarding Sanders’ likely declaration of his 2020 presidential candidacy. His campaign’s success will indicate just how much the left has made socialist messaging more mainstream for both Democrats and the general electorate. While the DSA is likely to endorse Sanders, sympathetic critics have pointed out the risks of doing so. Mainstream Democrats will likely be hostile to Sanders’ messaging even as they appropriate parts of his agenda. Sanders’ supporters will also be expected to back another Democrat should he lose the nomination, potentially reducing the DSA to another electoral auxiliary for the Democratic Party. Finally, there is uncertainty as to what exactly the DSA can independently contribute to Sanders’ campaign beyond that of Our Revolution.

Given these nuances, the choice between elections and social movements is more tactical than strategic. Put differently, it requires a shift from ideological struggles to political ones, and realizing them into institutional power. Radicalizing disaffected liberals by appealing to “socialist” values is in tension with the support for policies that speak to the interests of disaffected but largely non-politicized people. Short-term alliances with Democrats and progressive liberals, especially in congressional and local elections, may be necessary both as defensive and offensive measures. Defensive, to stave off right-wing assaults on democratic institutions (civil and political rights, including voting rights and birthright citizenship). Offensive, to challenge Republican hegemony in local and state legislatures across much of the country. Such a “Popular Front” would not mean a blanket support of Democratic Party candidates and policies, nor official endorsements (which should be extremely selective). Instead, such a progressive-left coalition would be contingent on the left’s ability to set the agenda on popular reforms such as health care, labour and reproductive rights, and immigration.

Looking Forward

One hundred years ago, the Bolshevik Party was able to channel the demands of the masses – peace, land, and bread – into a revolutionary political program. Today, the challenge facing American socialists is more daunting. Unlike the revolutionary wave that swept Europe in the aftermath of WWI, capitalism – in its regional, national, and global forms – remains hegemonic. However, the current crisis of capitalism and liberal democracy has produced cracks in the edifice. If we are currently living through an interregnum between a dysfunctional old order and an uncertain new one, the task of the American left is to articulate a convincing alternative vision to the current widespread societal discontent, economic inequality, and racial domination. Not only must this vision be transmittable to a broad spectrum of the population, it must also posit convincing, short-term, realizable reforms without tempering its long term goals for a total social transformation.

So far, the growing popularity of socialism has been bolstered by a handful of energetic electoral victories and a widespread sense that politics as usual is incapable of addressing the magnitude of the social problems facing the USA. At the same time, these challenges require a reevaluation of the left itself. Notions of a left simply comprised of a “movement of movements” or an amorphous multitude have revealed their limits. Growing a mass social movement requires turning outward the many ideological struggles within the left, transforming them into political struggles, and building tangible institutional power to achieve victory.

Despite positive signs, as of now, the left is yet to have a significant impact on the political balance of forces. As socialist ideas become more mainstream and popular amidst a broader, generational shift in the organization of class hegemony, they will also draw more scrutiny from both the right and the liberal center. At the same time, the left is confronted with its own internal growing pains, conflicts, and challenges. The left, therefore, remains a target of two old foes: repression and delegitimation from without, and self-destruction and cannibalism from within. How the American left navigates these waters in the run up to 2020 and beyond will reveal just how much mettle the current resurgence possesses. The real test of the left’s power and influence, in other words, is still to come. •

Originally published in Sociology of Power.

Endnotes

- Aziz Rana, “Goodbye Cold War,” N+1, Winter 2018.

- David Marcus, “The New Horizontalists”, Dissent, Fall 2012.

- Jodi Dean, Crowds and Party, (Verso 2016), p. 9.

- Mathieu Desan and Michael A. McCarthy, “A Time to Be Bold,” Jacobin, July 31, 2018; Dan La Botz, “The New Deal is Not Enough,” Socialist Forum, Fall 2018.

- DSA, “Chapter Organizing Call Notes,” February 24, 2017.

- See Benjamin Fong, “The DSA Community.”

- Benjamin Studebaker, “The Left is Not a Church.”

- Jeremy Gong, “DSA is at a Crossroads.”

- Carla Bergman and Nick Montgomery, “The Stifling Air of Rigid Radicalism,” The New Inquiry, March 2, 2018.

- Nancy Fraser, “The End of Progressive Neoliberalism,” Dissent, January 2, 2017.

- Thea N. Riofrancos and Daniel Denvir, “The Identity Politics Debate is Splintering the Left. Here’s How We Can Move Past It,” In These Times, February 14, 2017.

- Melissa Naschek, “The Identity Mistake,” Jacobin, August 28, 2018.

- Adolph Reed, “Response to Backer and Singh,” October 10, 2018.

- Nikhil Pal Singh and Joshua Clover, “The Blindspot Revisited,” October 12, 2018.

- Salar Mohandesi, “Identity Crisis,” Viewpoint, March 16, 2017.

- Ben Tarnoff, “Building Socialism From Below: Popular Power and the State,” Socialist Forum, Fall 2018.

- Vivek Chibber, “Our Road to Power,” Jacobin, December 2017.

- Ben Beckett, “Political Revolution in the Twenty-First Century,” Socialist Forum, Fall 2018.

- Charlie Post, “What Strategy for the US Left?” Jacobin, February 23, 2018.

- Gabriel Winant, “The New Working Class,” Dissent, June 27, 2017.

- Seth Ackerman, “A Blueprint for a New Party,” Jacobin, November 8, 2016.