Search for a Mass Politics: The DSA Beyond Bernie

Last November, in one of the most hostile rental markets in the world, in a city where a majority of residents are renters, a local rent control ordinance was defeated on the ballot by a margin of 38 per cent. In the year running up to Election Day, organizers, including our own local chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), were faced with a question of how to build the power of tenants in order to win things like rent control.

In the beginning, we pursued a two-pronged approach. We held meetings with tenants from specific developments and talked concretely about the issues they encountered there. Additionally, we engaged in door-to-door canvassing (of renters and homeowners alike) to gather the signatures needed to get rent control on the ballot. However, once the measure, Santa Cruz Measure M, was on the ballot, the temporal demands of the election subsumed all other organizing efforts. Canvassing for votes was king. Looking back, we think this experience may tell us a lot about why we were ultimately unable to pass rent control and build tenant power more broadly.

In the beginning, we pursued a two-pronged approach. We held meetings with tenants from specific developments and talked concretely about the issues they encountered there. Additionally, we engaged in door-to-door canvassing (of renters and homeowners alike) to gather the signatures needed to get rent control on the ballot. However, once the measure, Santa Cruz Measure M, was on the ballot, the temporal demands of the election subsumed all other organizing efforts. Canvassing for votes was king. Looking back, we think this experience may tell us a lot about why we were ultimately unable to pass rent control and build tenant power more broadly.

At the national level, the DSA is now facing a similar issue in our approach to another electoral project: the presidential candidacy of avowed democratic socialist Bernie Sanders.

DSA and Resurgent Left

Since 2016, membership in the DSA has exploded, from 5,500 to over 55,000 dues-paying members, grabbing mainstream attention and leading some to start referring to it as the “resurgent left.” Much of DSA’s growth can be attributed to the popularity of Senator Bernie Sanders’ first presidential campaign, which began in the spring of 2015. Within months of announcing his run, “socialism” was Merriam-Webster’s most looked-up word of the year and Sanders-approved policies like Medicare for All entered the mainstream political discussion with great favor. As a new presidential election cycle begins, Sanders remains the most popular politician in the country and, for those aged 35 and under, socialism polls more favorably than capitalism.1

But our organization, the DSA, was divided over whether to endorse his second run. A debate at our regional conference in Los Angeles yielded an even number of voices on both sides of the question. Since then, a poll of the general membership produced a 76 per cent to 24 per cent result in favor of endorsement, with significant abstention, and in March, the organization’s highest body followed that recommendation to officially endorse the candidate. While the outcome is clear, it’s still surprising that one in four members voted against a Sanders endorsement. Is it possible the poll was asking the wrong question?

In the debate, one vocal tendency has argued that popular socialist politicians, and Bernie in particular, are the only viable vehicle through which working-class power can be organized and a socialist program achieved. Those who disagree with the absolute terms of this argument are compelled to take an opposing position. The most obvious alternative to “Yes, endorse!” thus becomes “No.” But the issue is much more complicated, and its reduction to this “for or against” frame is symptomatic of a larger unresolved issue that has been haunting the organization: How do we ground our organizing in a materialist conception of class power? That is, what is the best way to become a part of the struggles that other working people – those who must become the subject of any mass socialist project – are involved in every day?

Hollow Exercise or Challenging the Rule of Capital?

Now that the DSA’s endorsement of Sanders is decided, it’s all the more important to tease out the niceties that have been lost in the debate so far. At stake is what kind of politics will dominate the emergent socialist movement in the US for years to come. Will we end up being an electoral machine and data farm, with socialism a parliamentary project to be carried out in a distant future, many election cycles away? Or can we weave together our workplaces, apartment buildings, schools, hospitals, and neighborhoods into a power that subsists here and now, responsive to the ever-changing struggles of the moment?

Making a conscious choice about our future means asking more questions.2 What is the strategic goal of supporting Sanders beyond and in relation to specific policy gains or electoral victories? What will the DSA do to ensure that a Bernie 2020 endorsement not only brings people closer to the organization, but involves them in a kind of politics beyond voting? In what ways does our electoral activity around Sanders increase the power and self-organization of working-class people and their ability to engage in struggle? What forms of political participation are best suited to develop and equip our class with the power it needs to directly challenge the rule of capital? How do the temporal demands of a two-year electoral cycle fit into a broader strategy for overthrowing capitalism? Unless we can answer these, endorsement is a hollow exercise.

In Pursuit of Mass Politics

Some have raised criticisms of Sanders’ record, citing concerns over his support of SESTA/FOSTA (Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act/Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act, legislation that critics say will make sex work more dangerous), his repetition of misinformation about Venezuela, his ambiguous “record of voicing both support for and criticism of the state of Israel,” and his recent vote to fund a border-security package that includes money for fencing and more border patrol agents.3 These are important criticisms that we don’t want to dismiss. But for argument’s sake, let’s accept that even if we significantly disagree with Sanders on these issues, there might be compelling reasons to become involved in the campaign of a self-styled democratic socialist: to connect with his supporters, to push the political discourse to the left, to stay relevant, and so on.

In her statement encouraging an endorsement of Sanders, DSA activist and Jacobin assistant editor Ella Mahony writes, “By participating in the Bernie movement, we can multiply our forces, meet and build relationships with people who can run as socialist candidates at every level, plug into Labor For Bernie, work to overcome the separation between labor and socialists, and transform DSA into something rooted in neighborhoods and workplaces of all kinds.” On its face, there’s nothing to disagree with here, but what’s less clear is the step between participating in an electoral campaign and becoming “rooted.”

It’s often argued, for instance, that Sanders provides a platform for the kinds of policies that would constitute the minimum of any respectable socialist program, carrying a message of “class-struggle politics” to all who will listen. From this, the argument implies, workers come to understand their real conditions and can begin to fight back accordingly. We thus hear of the desire to “advance a class-struggle perspective,” to “communicate a message,” and to offer a “positive vision for a radically fairer society.”4 These aspirations are fair enough, but the emphasis on spreading ideas appears to suggest, at times, that the reason why socialism does not yet exist is that people simply haven’t heard of it. Ultimately, the strategic relationship between the spread of socialist messaging and the accrual of working-class power is fuzzy, at best.

Receptivity to socialist ideas did not begin with Bernie. In the United States, the financial crisis and Great Recession that began in 2008 and the neoliberal orientation of the Obama Democratic Party surely set the stage. Out of these conditions, the first stirrings of a “class-struggle perspective” in the United States came, most notably, from the Occupy Wall Street movement, which became a national phenomenon. The “positive vision for a radically fairer society” did not spontaneously arise out of stump speeches, but out of historic movements like Black Lives Matter; Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) against Israel; and the Arab Spring – that is, out of the refusal, rebellion, and self-organization of working people themselves around the world. It is one thing to know which way the wind blows, but it is quite another to conclude, as one author recently has, that Sanders is the “storm that generates that wind.”5

Without recognizing the material basis for the re-emergence of a robust US socialist movement and the power of the working class – something that goes beyond the membership numbers of the DSA – we risk falling into a kind of idealist trap. We might think, for instance, that the growth of the possibilities for socialism is just a gradual accumulation, a linear and continuous accretion of partisans to our cause and resources at our disposal. But, as the Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin once pointed out, politics is more like algebra than arithmetic: Changing variables may even invert the value of an entire equation, turning what was positive in one instance into a negative in another.6 Even popular electoral victories in socialism’s favor have transformed, suddenly, into its largest defeats, as in Chile after the 1970 election of socialist Salvador Allende.

The twentieth century offers many examples of election-focused parties that were able to increase their membership and voter support without translating that into a revolutionary strategy. Historian of European socialism and democracy Geoff Eley notes:

“There are all sorts of ways of using the electoral process as a vehicle, as an instrument, as a platform, as an arena in which you argue the importance of your particular kind of politics – as opposed to the electoral machinery that the Social Democratic and Communist Parties simply became. During the course of the later twentieth century, the whole raison d’être of the party became reduced downwards into fighting an election, winning an election, keeping itself in office, or getting back there.”7

There are potential opportunities in engaging in electoral politics, but there is also the pitfall of using elections and organizational growth as a means of deferring essential strategic questions. To avoid this from the outset, the notion of accumulating support for working-class or socialist politics needs to be put on a material footing: What are the concrete goals of winning people over to democratic socialism? What kind of organization are we building, and how do we get supporters to be a part of that? What other movements or spaces provide opportunities for working-class organization, and how do we relate to them? What do we need to do to create continuities across the inevitable ups and downs of explosive mobilization? In short, we need a strategy that goes beyond changing minds, spreading a message, or getting votes, however important these may be as part of a larger project.

Our argument on this point is simple: Electoral organizing, as a primary mode of doing politics, is incapable of building the type of power required to fundamentally shift the balance of forces away from the well-organized and well-funded global capitalist class. To be clear, this does not mean that we should not vote, run candidates, or push for legislative reform. But it does mean that we should have a clear understanding of just how far these activities can take us. Moreover, more work is needed to think through how one form of activity – electoral organizing around Bernie Sanders – translates into the kind of mass, militant organizations that we envision.

Political Forms

Lacking an understanding of the limitations of electoral politics and the struggle of ideas, we are likely to just assume that changed minds are permanently changed, and that once we create a spark at the level of ideas, or within the spectacular arena of electoral politics, more radical consequences are sure to follow.

David Thompson, a member of Philly Socialists, recently offered up a compelling analysis of the various tendencies in the DSA.8 While his portrayal flattens these tendencies a bit, he offers an important cautionary note about the assumptions that take over when we lack a materially grounded strategy, which is to say, a strategy that is rooted in the activity of the class:

“It’s almost as if both sides in the debate believe the power is already there in the class, it just needs to be activated, turned on, by the right socialist ideas. The DSA ‘right’ will talk about the ‘millions who voted for Bernie Sanders’ or [about] unionized teachers as if they’re sleeping giants – which, potentially yes, but if the liberals keep out-organizing us and winning deeper bases in the class? No. The ‘left’ is less prone to these kinds of ‘the class is on the march’ type statements, but they are also less ready to explain how their approach leads to more working-class power.”

We can’t assume, in other words, that the socialist masses are waiting in the wings, ready to enter onto the stage of history after watching a few Bernie speeches or reading some articles online. These activities may spark an interest, but Thompson is right that our movement and the power of the working class in general will only grow if we can also create opportunities for people to become active and organize themselves. It is one thing for someone to acknowledge, for instance, that the rent is too damn high, but another for them to link up with their neighbors, form a tenants union, confront their landlord over shitty conditions, organize for rent control, or launch a rent strike.

Thompson is also correct that we’re not operating in a vacuum. Strategy means considering the moves of others, thinking about eventualities that are outside our control. One consideration is the jockeying of and within a Democratic Party that is undeniably in flux. If our tasks are different in this election compared to 2016, the conditions will be too. We’ll face competition from those seeking to incorporate their own lessons from the last time around to hold the party’s reins, or, alternatively, to opportunistically use the discourse of socialist politics to advance their own position.

Compared to the last election, Sanders will be one in a larger and more varied field of candidates. It may therefore be difficult for voters to distinguish Bernie’s view of democratic socialism from Elizabeth Warren’s support for Medicare for All, the Green New Deal, and worker participation on corporate boards. If the most obvious referent of both candidates’ policies is the liberal New Deal, will it be decisive that Bernie talks about socialism and Warren about “accountable capitalism”? There are important differences between these candidates, and Warren is most likely tacking left on these issues in part because of Bernie’s success at publicizing them in 2016, but the real distinctions might not be obvious to the casual voter – certainly not as obvious as those between Clinton and Sanders in 2016.9

Another consideration: What if Bernie loses? A Bernie loss could just as easily lead to an expansion of the Democratic Party’s Big Tent rather than add a new layer of adherents to the ranks of autonomous democratic socialism. Many media narratives already reduce Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to representatives of the left wing of the Democratic Party. If democratic socialism is to mean more than that, we need to work against this tendency.

Ultimately, to define democratic socialism means not just proposing policies and demands, or offering up new slogans. Political content is only half the game. Radical change requires us to think about political forms, different modes of doing politics.

Voting and media consumption are, no doubt, major modes of political engagement for many Americans, which is one of the arguments for participating, strategically, in the presidential election process. On the other hand, even at peak US voter participation, nearly one-third of those eligible choose to abstain. This is not to mention the millions of workers in the United States who are not eligible to vote – disproportionately black and brown – either for having been incarcerated or for not having the right passport. And recently Republicans have cut many more from the voting rolls. Unless it’s possible to vote socialism into existence – we think it’s not – then our task is to transform the meaning of political participation and activate the excluded and apathetic. Voting and reading, and even canvassing and calling, must give way to organizing in our workplaces and neighborhoods, making demands on our bosses, shutting down freeways, and refusing to be limited by the horizons defined for us by politicians.

Competing Forms of Housing Politics

In California, a sober assessment of recent work on housing issues further demonstrates the need to move beyond an electoral conception of mass politics. Prior to the election this past November, DSA chapters throughout California participated in canvassing for Proposition 10, a ballot initiative that would expand rent control protections for tenants living in some of the most expensive and inhospitable rental markets in the world. Much of this work was coalitional, with groups like Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment, or ACCE, a large, multi-issue nonprofit, taking the lead. In practice, it amounted to hundreds of enthusiastic DSA members using voter rolls to target likely voters (who are also more likely to be homeowners), by going door to door, engaging people as atomized individuals, and convincing them to Vote Yes on 10. While this work allowed many tenants to share their frustrations with DSA members eager to lend an ear, it is less clear what kind of lasting capacity was built out of this form of organizing.

With millions and millions of dollars pouring in from around the country to defeat it, Proposition 10 failed. Debates about how to recover our momentum around housing justice have resulted in two distinct conceptions of politics. On the one hand, some have proposed a rewriting of the same initiative, tweaking various parts of it to satisfy the concerns of those swing voters who said they might have supported it, but didn’t like this or that language in the bill. The focus on crafting the “right” legislation, however, misses the point: Our defeat signaled that working-class people – tenants – did not have the capacity to defeat money. So we’re faced with the choice: either offer a watered-down version of the initiative (which presumably would have a better chance of passing with “statistically likely voters”), or build the tenant power needed to make it pass.

As we described in the introduction, in the city of Santa Cruz our DSA chapter faced a similar set of issues around Measure M, a local rent control measure. When we began campaigning, we hoped the election would jump-start some simmering efforts at organizing a tenants union. The measure would provide, we reasoned, a strong basis for talking to tenants about their housing conditions. We imagined that neighborhood committees tasked with regular canvassing could be the mechanism through which broader tenant organizing could occur.

Unfortunately, the pressures of the election made this “let’s do both” approach increasingly difficult. Some, even when recognizing the need for tenant organizing, thought that the specifically electoral aspects of the work needed to come before anything else – writing the measure, collecting voter data, leaving flyers on as many doors as possible, publishing information about the details of the ordinance, and disputing the details that were constantly mischaracterized by a well-funded opposition. On the other hand, how could the campaign make lasting gains if we did not build a strong tenants movement in the process? Even if we had passed rent control, we would have to be ready to defend it when, inevitably, it came under attack in the courts or in future elections. Since we lost the election, we were left with a fractured coalition of activists who had come together specifically around the campaign and no obvious way forward. While we brought attention to the issue of tenants’ rights and living conditions, we didn’t build power for working people, for the local socialist movement, or even, for the most part, for our chapter.

What we did have were hundreds of anonymous email addresses, which have now been compiled into a list that gets blasted whenever the city council discusses anything related to housing. Contrary to expectations, access to this data has not resulted in the kind of upheaval necessary to thwart the aspirations of what is now a very well-organized landlord class. This fact is important; many have argued that we should build our own email lists and data while canvassing to ensure that we walk away from these campaigns with something usable. But building an email list is no substitute for building the kind militancy, trust, and collectivity needed to beat back the bosses, the landlords, the white supremacists, and the cops.

Crafting popular legislation that can persuade given constituencies, spending money to publicize simple messages, and using largely unidirectional forms of mass communication is one mode of politics – the predominant approach to elections among capitalist parties today. The alternative, however, is to create our own constituency. This is not a question of demographics; it means organizing venues of collective agency that don’t require us to play by the rules of game.

One model of tenant organizing that occurred alongside the Proposition 10 campaign was put forward by a group of East Bay DSAers organizing under the banner of, which stands for Tenants and Neighborhood Councils. TANC’s conception of how to build tenant power differs from the more electorally oriented members of the organization in that they conceive of tenants’ power as the ability of tenants to withhold their rent. It might take a lot of work to get to that point, but like workers’ ability to collectively withhold their labor, renters, when united, can use this collective threat to win immediate gains from their landlord. The type of organizing that is required to build this capacity is one that can easily lend itself to electoral action, if appropriate, whereas the inverse doesn’t appear to be the case.

In Oakland, TANC successfully organized 41 buildings operated by the same landlord and pressured her to change subtenant policy, which required new tenants to earn three times “market rate” rent, even though the rooms being rented were rent controlled. In Los Angeles, the LA Tenants Union also has used the rent strike as a weapon against landlords with some measure of success.

Asking the Right Questions

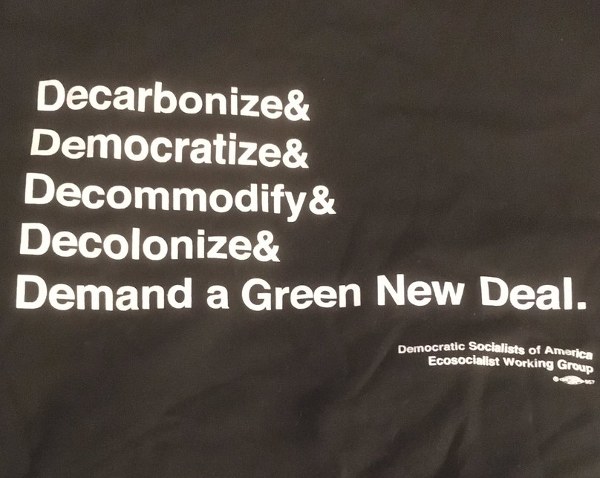

Clearly, one of the key questions moving forward is, What kind of power do we need to build to increase our class’ ability to directly challenge the rule of capital where we live and where we work? Electoral activity, despite what happened in 2016, does not automatically translate into the types of self-organization and self-activity needed to open new fronts for class struggle. Where, for instance, is the class organization that will apply this kind of pressure to ensure that a truly radical Green New Deal is enacted? If this organization does not already exist, how we can throw all of our resources to bring it into being?

What will the DSA do to ensure that our activity around Bernie 2020 amounts to more than just a mass canvassing operation that steers people back into the spectacle that is Democratic Party politics? What will our organization do to avoid resurrecting the sort of email-listserv politics that characterized the anti-war movement during the Bush era, to avoid DSA becoming a “moveon.org” for the Twitter generation? What sort of political education can we offer to fuel peoples’ new curiosity about socialism? How can we inoculate ourselves against the attractions of opportunistic politicians? These are the questions that should guide our strategic orientation toward whatever activity we engage in, whether that be the Sanders campaign, labor organizing, tenant organizing, anti-racist organizing, or any of the other political projects DSA members are involved in.

In 2016, Sanders called for a political revolution. It was inspiring. But the paradox of a revolution is that it always leaves behind the conditions that spark it. We can take inspiration from the past and use what tools we’ve got in the present, but building a different future is on us. We can’t wait until we have all the answers, of course, but let’s start asking the right questions. •

This article first published on the New Politics website.

Endnotes

- “The Resurgent Left: Millennial Socialism,” Economist, February 14, 2019; Alison Flood, “Socialism the Most Looked-Up Word of 2015 on Merriam Webster,” Guardian, December 16, 2015; John Haltiwanger, “Bernie Sanders Is the Most Popular US Politician, Even as Some Blame Him for Clinton’s Loss,” Newsweek, August 25, 2017.

- Dan Parker, “Berning Questions: What’s the Play for DSA?” Medium/dapski411, February 20, 2019.

- Eric Corelessa, “Where Does Bernie Sanders Stand on Israel?,” Times of Israel, February 1, 2016; Alan Macleod, “Venezuela-Baiting: How Media Keep Anti-Imperialist Dissent in Check,” FAIR, March 5, 2019; Madeleine Freeman, “Sanders Votes for Increased Border Security Despite Progressive Opposition,” Left Voice, February 20, 2019.

- Robbie Nelson, “Bernie and Class Politics,” The Call, December 6, 2018; Bhaskar Sunkara, “Sanders Started a Revolution in 2016. In 2020 He Can Finish It,” Guardian, February 19, 2019.

- Meagan Day, “Bernie is Running, Thank God,” Jacobin, February 19, 2019.

- Vladimir Lenin, ‘Left-Wing’ Communism: An Infantile Disorder, trans. Julius Katzer (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1964). Accessed here. Original publication 1920.

- Geoff Eley, “The Committee Room and the Streets,” interview by Salar Mohandesi, Viewpoint, September 2, 2014.

- David Thompson, “DSA’s Left and Right Both Miss the Point: We Need to Build the Left and the Working Class Together,” The Left Wind, January 26, 2019.

- Bhaskar Sunkara, “Think Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren are the same? They aren’t,” The Guardian, February 19, 2019.