Nicaragua: The Other Revolution Betrayed

The violent repression against demonstrators protesting brutal neoliberal policies, which resulted in more than 300 people being killed by regime forces since April 2018, is just one of the reasons why different leftist social movements have condemned the Nicaraguan regime led by President Daniel Ortega and Vice-president Rosario Murillo. The Left has many more reasons to denounce the policies of the regime. To understand this, we must go back to 1979.

The Sandinista Revolution

1979 saw the victory of an authentic revolution in Nicaragua that combined a popular uprising, self-organization of cities and neighborhoods in rebellion, and the action of the Sandinista National Liberation Front (in Spanish – Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional – FSLN), a political-military organization inspired by a Marxist-Guevarist/Castrist model. The revolution put an end to the 42 year-long authoritarian rule of the Somoza dynasty, which had appropriated the state (its armed forces, administration and significant parts of its economic assets) and established a strong alliance with the United States – the Somoza dictatorship proving to be an effective bulwark against progressive political forces – whose multinationals could maintain and increase their plundering of Nicaragua’s national resources in exchange for commissions which added to the increasingly important wealth of the Somozas.

1979 saw the victory of an authentic revolution in Nicaragua that combined a popular uprising, self-organization of cities and neighborhoods in rebellion, and the action of the Sandinista National Liberation Front (in Spanish – Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional – FSLN), a political-military organization inspired by a Marxist-Guevarist/Castrist model. The revolution put an end to the 42 year-long authoritarian rule of the Somoza dynasty, which had appropriated the state (its armed forces, administration and significant parts of its economic assets) and established a strong alliance with the United States – the Somoza dictatorship proving to be an effective bulwark against progressive political forces – whose multinationals could maintain and increase their plundering of Nicaragua’s national resources in exchange for commissions which added to the increasingly important wealth of the Somozas.

The FSLN was founded in the 1960s as a leftist group opposing the government mainly through guerilla warfare. It was not until some of its guerillas spectacularly took high-ranking members of the Nicaraguan ruling classes as hostages, in December 1974, that it was considered a potentially serious threat to the Somocista dictatorship. Earlier that year, liberal fractions of the bourgeoisie, opposing the concentration of wealth and power in the hands of the Somoza ruling clique, had already formed the Democratic Union of Liberation (in Spanish – Unión Democrática de Liberación – UDEL) under the leadership of Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal, editor of the liberal newspaper La Prensa, to try and gather political momentum in favor of the liberalization of the regime. After the stunt of the Sandinista guerillas, the regime declared a state of emergency, increased its repressive grip over the Nicaraguan society and hunted down the FSLN.

Faced with increasing difficulties, the FSLN eventually split into three factions. The “prolonged people’s war” faction stayed loyal to the strategy of accumulating forces in the remote areas until they would have enough strength to liberate entire regions of the country and launch a final assault against Somoza’s army. The “proletarian tendency” emerged in order to challenge the prolonged people’s war strategy, considered not to be adequate given the absence of a permanent occupying army (hence the rural populations would not directly witness the imperialist endeavor and would not massively join the guerilla) and the development of a capitalist mode of production in the country (the economic development of the 1950s and 1960s had given rise to an agricultural and an industrial proletariat, which constituted respectively 40% and 10% of the active population by 1978). The “proletarian tendency” therefore focused on organizing mass working-class organizations in urban areas and gaining the support of industrial workers with the perspective of launching a swift insurrection when the conditions to do so would be met. Finally, the “Terceristas,” whose main figures included Daniel Ortega and his brother Humberto, also advocated for an insurrectional strategy, but were open to tactical alliances with the liberal fractions of the bourgeoisie opposing Somoza. While the “proletarian tendency” stressed the need for a mass uprising and for self-organization, the “Terceristas” displayed substitutist tendencies which implied that an armed insurrection led by organized guerillas, without a simultaneous mass uprising, would be sufficient to overthrow the regime and take power.

Eventually, the regime lifted the state of emergency in 1977, thinking the guerilla war was defeated and the conditions for entering negotiations with the liberal opposition were met. But FSLN groups were prompt to resume their armed actions in urban areas. In January 1978, the murder of Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal by the regime’s soldiers was caught on video and sparked anger among the liberal opposition as well as among the toiling masses. A general strike supported by the liberal bourgeoisie was launched while FSLN groups staged armed actions against Somoza’s National Guard. In August, another general strike was called, while Sandinista guerillas staged an assault against the National Palace where a joint session of both chambers of the Parliament was taking place, taking hundreds hostage, which successfully resulted in the liberation of several political prisoners from Somoza’s jails. More importantly, spontaneous uprisings took place against the regime, enabling the Left to gain momentum over the liberal opposition. This culminated in several urban uprisings in September 1978 after the FSLN called for insurrection. While these uprisings were severely defeated by the National Guard, they scared away the liberal opposition whose representatives sought to enter negotiations with the regime, mediated by the U.S.-dominated Organization of American States (OAS). The “Terceristas” denounced it and withdrew from the “Broad Liberation Front” (in Spanish – Frente Amplio Opositor – FAO) which they had constituted together with the liberal opposition, paving the way for the reunification of the three Sandinista currents.

In January 1979, Somoza turned down the proposals of the liberal opposition. The momentum was then with the Sandinistas, who dominated the new “Patriotic National Front” (in Spanish – Frente Patriótico Nacional – FPN), created in February 1979 and in which the liberal opposition was marginalized. After reuniting, the FSLN called for a general strike to be held in June, and prepared a broad military offensive to be launched at the same time.

The population effectively accompanied these actions through mass urban uprisings. As the armed insurrection quickly liberated areas of the country one after the other, Somoza’s army largely decomposed and, when its last stronghold in the capital was finally liberated on July 19, 1979, its last remnants had no choice but to flee abroad (in particular to the neighboring country of Honduras). Now in the government, the revolutionary political forces, among which the FSLN was dominant, pledged to install a democratic regime, to guarantee a non-alignment of Nicaragua’s foreign policy (thus putting an end to the alliance with the United States) and to develop a “mixed economy” in which the development of cooperatives and state-owned enterprises would be encouraged while the existence of private capital would not be fundamentally threatened as long as it was perceived as “patriotic,” that is, loyal to the Sandinista revolution rather than to the overthrown Somocista regime or to U.S. imperialism.

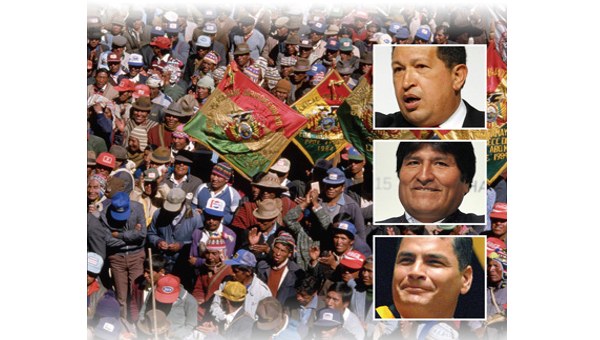

During the first two years following the revolutionary victory, several developments made the case of Nicaragua different from other cases in which the Left has come to power through elections in Latin America, including Chile in 1970, Venezuela in 1998-99, Brazil in 2002-03, Bolivia in 2005-06 and Ecuador in 2006-07. Due to the destruction of Anastasio Somoza’s army and the flight of the dictator, the FSLN not only assumed governmental power (which the other cases cited did via the electoral process), it also replaced the Somocista army with a new army that was put at the service of the people, took over total control of the banks and decreed a public monopoly on foreign trade. Weapons were distributed to the population for their self-defense due to risks of outside aggression and an attempted coup coming from the Right. These are fundamental changes that did not take place in the aforementioned countries. They did take place in Cuba between 1959 and 1961, and were extended during the 1960s.

In the 1980s, major social progress was made in Nicaragua in the areas of healthcare, education, improving housing conditions (even if they remained rudimentary), fuller rights to organization and protest, access to credit for small producers thanks to nationalization of the banking system, and more. These represented undeniable progress.

However, throughout the 1980s the FSLN government had to fight a decade-long war against the counter-revolutionary forces known as the Contras, heavily supported by the United States which could never satisfy its ambition of direct military intervention to topple the Sandinistas but settled for a “low-intensity” conflict which would strangle Nicaragua economically and isolate the FSLN politically. U.S. imperialism and its vassals (such as the regime of Carlos Andrès Perez in Venezuela or dictatorships as in Honduras) found it necessary to contain the spreading of this extraordinary experiment in social liberation and renewal of national dignity. In fact, social revolt was rampant in the region, in particular in Salvador and Guatemala where revolutionary forces close to the Sandinistas had been active for decades.

In 1990, the FSLN lost the general election to the Right, with Violeta Chamorro, the widow of Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal, being elected President. Under Chamorro, Nicaragua was to fully embrace the neoliberal austerity promoted by the “Washington consensus,” which was to result by the end of the decade in Nicaragua becoming the second poorest country in the Americas, after Haiti.

Change Society Without Taking Power?

In the 1990s, as a result of disappointed hopes, there were those who were saying that what is needed is to try to change society without taking power. One aspect of their approach was quite pertinent: it is absolutely vital to promote processes of change that take place at the base of society and which presuppose self-organization by citizens, freedom of expression and freedom to demonstrate and organize. But the idea that power must not be taken is not valid, because it is not possible to really change society unless the people take power at the level of the State.

The question is rather: how to build an authentic democracy in the original sense of the word – that is, power exercised directly by the people for the purpose of emancipation? In other words, power of the people, by the people and for the people.

We feel that it was necessary to overthrow the Somoza dictatorship through the combined action of a popular uprising and the intervention of a political-military organization. And as such, the victory of July 1979 remains a popular triumph worthy of celebration. It must be stressed that without the ingenuity and tenacity of the people during the struggle, the FSLN would not have succeeded in striking the decisive blow against the Somoza dictatorship.

The FSLN leadership did not go far enough in radicalization for the benefit of the people.

Several questions arise. Did the FSLN go too far in the changes it made in the society? Did it take the wrong direction? Or are the disappointing subsequent developments the result of aggression by North American imperialism and its allies – in Nicaragua and elsewhere in the region?

Here, we will highlight errors made in two main areas.

First, the FSLN leadership did not go far enough in taking radical measures in favor of the segments of the population who were most exploited and oppressed (beginning with the poor rural population, but also factory workers and healthcare and education workers, who were generally underpaid). It made too many concessions to agrarian and urban capitalists.

Second, the leadership of the FSLN, with its slogan “National Directorate – Give us your orders!” did not provide sufficient support for self-organization and worker control. It placed limits that were highly detrimental to the revolutionary process.

Of course, responsibility for the outbreak of the war lies exclusively with the enemies of the Sandinista government, the latter of which had no choice but to confront the aggression. Nevertheless, errors were made in the means of waging the war: Humberto Ortega, the head of the army, formed a regular army equipped with expensive heavy tanks, unsuitable against the guerrilla methods of the Contras, and the conscription of the country’s youth in order to reinforce the army was also badly perceived by the population. This, combined with the errors made in the area of agrarian reform, had damaging consequences. In a recent interview, Henry Ruiz, one of the nine members of the national leadership in the 1980s, underlines the fact in these terms:

“The campesinos were not favored [in agrarian reform]; on the contrary they were affected by the war. The war waged by the contra and the war waged by us.”

Errors Made by the Sandinista Leadership

What errors were made? Here is a summary presentation of a question that deserves long discussion.

The agrarian question was not dealt with properly. Agrarian reform was seriously insufficient and the Contras took full advantage of that fact. Much more land should have been distributed to rural families (giving them title to the property), because expectations were enormous among a large part of the population who needed land and were struggling to have the arable land in the large private estates – including (but not only) those belonging to the Somoza clan – distributed to those who wanted to work it. The orientation that won out among the Sandinista leadership was to target the major Somoza estates but to spare the interests of major capitalist groups and powerful families whom certain Sandinista leaders wanted to turn into allies or fellow travelers.

Another error was made: the FSLN wanted to quickly create a State agrarian sector and cooperatives to replace the large Somocista estates, which was not in line with the attitudes of the rural population. Priority should have been given to small (and medium) private farms, distributing titles to the property and providing material and technical aid to the new campesino owners. Priority also should have been given to support for production for the domestic market (which was already substantial but could have been improved and increased) and the regional market, making maximum use of organic-agriculture methods.

To sum up, the leadership of the FSLN combined two serious errors: on the one hand, it made too many concessions to the bourgeois who were considered allies in the change then in progress, and on the other hand it engaged in excessive statism or artificial cooperativism.

The result was not long in coming: a part of the population, disappointed by the decisions of the Sandinista government, was attracted by the Contra. The latter had the intelligence to adopt a discourse that was aimed at the disillusioned campesinos, telling them that they would help them overthrow the FSLN, resulting in a truly fair distribution of land and true agrarian reform. This was deceitful propaganda, but it was widely disseminated.

That is corroborated by a series of studies in the field – which Éric Toussaint, one of the authors of this article, had access to from 1986-1987, after several trips made to Nicaragua to provide internationalist solidarity – in particular studies led in rural regions where the Contra had gained popular support. Certain entities within the Sandinista movement itself conducted very serious surveys on the ground and alerted the Sandinista leadership about what was happening. These included the work coordinated by Orlando Nuñez, whose later political evolution led him to remain loyal to Ortega despite his initial left-wing Sandinista stance. Work done by other entities independent of the government and related to Liberation Theology came to the same conclusions. A number of rural organizations linked to Sandinism (UNAG, ATC, etc.) were also aware of the problems, but engaged in self-censorship. And internationalist experts specialized in the rural world also sounded the alarm.

Concerning self-organization and worker control, the FSLN inherited the Cuban tradition, which promotes popular organization, but within a very controlled and limited framework. Cuba, which at the start of the 1960s had experienced a broad movement toward self-organization, gradually moved toward a model in which there is much greater control from above, starting with the increase in Soviet influence in the late 1960s-1970s. And part of the FSLN leadership was trained in Cuba at that time. The decade after 1970 has been defined as the “grey period” by an entire generation of Cuban Marxists. In short, the Sandinista leadership inherited a tradition that was strongly influenced by the bureaucratic degeneration of the Soviet Union and its destructive impact on a large part of the Left internationally, including in Cuba.

Similarly, the application, starting in 1988, of a structural adjustment program that strongly resembled the programs dictated to other countries by the IMF and the World Bank is another error made by the Sandinista government. Regarding this question, Sandinista members have made their criticism of the orientation that was taken by their leadership very clear. They expressed their point of view both internally and publicly, but unfortunately no correction of the errors ensued. The government extended a policy that was leading the process straight into a wall and would result in popular rejection at the polls and a victory of the Right in the election of February 1990.

It was not overly radical policies that weakened the Sandinista revolution. What prevented it from advancing sufficiently with the support of a majority of the population was its failure to put the people at the core of the transition that followed the overthrow of the Somoza dictatorship.

In short, the government maintained an economic orientation that was compatible with the interests of Nicaragua’s wealthy bourgeoisie and major private foreign corporations – that is, an economy oriented toward export and based on low wages in order to remain competitive on the worldwide market.

This was not doomed to happen – alternative policies could have been implemented. The government should have paid more attention to the needs and aspirations of the people, in rural as well as urban areas. It should have redistributed land for the benefit of the campesinos, developing and/or strengthening small landholding and, to the extent possible, forms of voluntary cooperatives. The government should have promoted wage increases for workers, both in the private and public sectors.

If the Sandinistas had really wanted to break away from the export-oriented extractivist model that depends on competitiveness on the international market, they should have gone against the interests of the capitalists that still dominated the export-oriented extractivist industry. They should have done more to gradually implement policies in favor of the small and medium-sized producers who supplied the domestic market, such as protectionist measures in order to limit importations. This would have allowed the peasants and small and medium enterprises not to have to make sacrifices for the sake of competitiveness on the international market.

Instead of encouraging the masses to follow orders given from the top of the FSLN, self-organization by citizens should have been promoted at all levels, and citizens should have been given control over the public administration as well as over the accounts of private companies. The political institutions that were installed by the FSLN did not fundamentally differ from the ones of a parliamentary democracy with a strong presidential role, something which would impede the capacity of the masses to constitute a counter-power when the Right would be elected in 1990.

Concessions were made to local big capital, which was wrongly perceived as being patriotic and an ally of the people: the increases in wages were limited, fiscal incentives in the form of lower taxation were given to the bosses. Any such alliance should have been rejected.

At each important stage, criticism from within the FSLN emerged. The magazine Envio, for instance, was founded in 1981 “as a publication that provided ‘critical support’ to Nicaragua’s revolutionary process from the perspective of liberation theology’s option for the poor.” But such criticism was not actually taken into account by the leadership, which was more and more dominated by Daniel Ortega, his brother Humberto, and Víctor Tirado López – all three of whom supported the “Tercerista” faction (which, as was explained above, did not have a full understanding of the necessity of self-organization, and was inclined to alliances with the bourgeoisie) and were joined by Tomas Borge and Bayardo Arce of the “prolonged people’s war” faction. Further, the four other members of the national leadership did not form a bloc to oppose the continuation and deepening of the errors that were made.

It is very important to point out that proposals for alternative policies were formulated both inside the FSLN and from outside, from political groups who wanted to further the revolutionary process that was underway.

Constructive critical voices did not wait for the electoral failure of February 1990 to propose new directions, but they received only a limited hearing and remained relatively isolated.

Illegitimate and Odious Debt

The leadership of the FSLN should also have questioned repayment of the public debt inherited from the Somoza dictatorship and should have broken with the World Bank and the IMF. As a dependent country aligned on the United States, Somoza’s Nicaragua had been a receiver of booming foreign lending in the 1970s, by multilateral institutions such as the World Bank and the IMF as well as by international private banks. While the loans were officially intended for development, they benefitted the strengthening of an authoritarian regime and the increase in wealth of Somoza and his clique. After the latter left the country with most of their assets, the new Sandinista rulers of Nicaragua were in dire need of funding in order to implement progressive policies and to encourage the industrialization of the country. Somoza’s debt would soon be a burden and impede the implementation of such policies. When the FSLN took power, the foreign debt stood at $1.5-billion, and in 1981 its servicing represented 28% of the country’s export revenue.

The Sandinistas should have conducted an audit of the debt with broad citizen participation. This is a fundamental point. The Sandinista government’s agreeing to continue repaying the debt was in keeping with its defense of the interests of a part of Nicaragua’s bourgeoisie who had invested in the debt issued by Somoza and borrowed money from U.S. banks. For the Sandinista government, this was also a way of avoiding a confrontation with the World Bank and the IMF, despite the fact that they had financed the dictatorship. Despite the government’s efforts to maintain collaboration with the two institutions, the latter decided to suspend financial relations with the new Nicaraguan authorities. This shows that it was useless to make concessions to them.

Admittedly, it was not easy for the government of a country like Nicaragua to face its creditors alone, but it could have begun by questioning the legitimacy of the debts claimed by the World Bank, the IMF, and the States and private banks that had financed the dictatorship. The government could have launched an audit of these debts by calling for citizen participation, and could have gained support for a demand for abolition of those debts by the broad international movement in support of the Nicaraguan people.

Instead, in 1988 after the external debt had reached $7-billion, the government went as far as implementing a structural adjustment plan that degraded the conditions of the poor without affecting the rich, very much resembling the usual conditions imposed by the IMF and World Bank while these institutions had still not resumed their financial relations with Nicaragua.

It can never be repeated often enough that a refusal to stand up to creditors who demand repayment of an illegitimate debt is generally the beginning of the abandonment of the program of change. If the burden of illegitimate debt is not denounced, the people are condemned to bear that burden.

In 1979, two months after the overthrow of Somoza, Fidel Castro said in a speech before the General Assembly of the United Nations:

“The developing countries’ debt has already reached $335-billion. It is estimated that the total payment for servicing the foreign debt amounts to more than $40-billion each year which represents more than 20 per cent of their annual exports. Furthermore, the average per capita income in the developed countries is now 14 times greater than that of the underdeveloped countries. This situation is already unbearable.”

At the Continental Dialogue on the Foreign Debt held at Havana’s Palace of Conventions on August 3rd, 1985, he said: “The debts of the countries with less relative development in a disadvantaged situation are unbearable and do not have a solution, and they should be cancelled.”

As part of a major international campaign for the abolition of illegitimate debt, Castro made a series of arguments at that conference that are quite applicable to Nicaragua’s case:

“To all these moral, political, and economic reasons, we can add many legal reasons: Who signed the contracts? Who is sovereign? On the basis of what concept can it be said that the people committed themselves to paying and that they signed for the credits and received the credits? Most of those credits were secured by repressive military dictatorships that did not consult the people. Do the debts and the commitments of the peoples’ oppressors have to be paid by the oppressed? This is the moral and philosophical basis of this idea. The parliaments were not consulted. The principle of sovereignty was violated. What parliament participated in this debt-signing process and knew about it?”

We stress the issue of illegitimate debt because, should the oppressive regime of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo be overthrown, it would be essential for a popular government to call repayment of the debt demanded of Nicaragua into question. Should the Right take leadership of the overthrow of the regime, we can be certain that it will not call the debt repayment demanded of Nicaragua into question.

After the defeat in the election of February 1990, Daniel Ortega extended a policy of class collaboration.

In 1989 the FSLN government reached an agreement with the Contras that put an end to fighting, which was of course a positive development. It was presented as the victorious outcome of the strategy that had been adopted. Yet it was a Pyrrhic victory. The Sandinista leadership called a general election in February 1990 and felt certain it would win. Election results struck the Sandinista leadership with an amazed wave of panic: the Right had won, partly by threatening that fighting would resume if the FSLN won. Many people wanted to avoid further bloodshed and thus reluctantly voted for the Right, hoping for an end to war for good. Some were also disappointed by the FSLN government’s policies in the countryside (deficient agrarian reform) and in cities (negative consequences of the austerity measures enforced by the structural adjustment program begun in 1988) though Sandinista organizations could still rely on a lot of support among young people, workers and civil servants, as well as among a significant number of farm labourers.

The Sandinista leadership expected to reap 70% of the votes in the elections, so it was flabbergasted, as it hadn’t perceived the growing discontent in a large portion of the population. This illustrates the gap between the majority of the people and a leadership that had become used to giving orders.

After the defeat in the election of February 1990, Daniel Ortega adopted an attitude that swung back and forth between compromise with the government and confrontation.

The Sandinista leadership, with Daniel and Humberto Ortega at its head, negotiated the transition with Violeta Chamorro’s new government. Humberto was still General in Chief of a starkly reduced army. The most left-wing members of the army had been dismissed, under the pretext that they had supplied missiles to the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), which was still attempting to bring about a general uprising in Salvador. In the context of presidents Gorbachev and Bush coming closer together, Soviet authorities had denounced the fact that SAM-7 and SAM-14 missiles that had been supplied by the USSR to the Sandinistas had been passed on to the FMLN and used to shoot down U.S. army helicopters operating in El Salvador. Four Sandinista officers were imprisoned on an order from Humberto Ortega with the following explanation: “Blinded by their political passion and guided by extremist arguments, this small group of officers flouted military honor and the Institution’s and Military Command’s loyalty, which is the same as flouting the sacred, patriotic and revolutionary interests of Nicaragua.”

This led to strong criticism from the Workers’ National Front (which included Sandinista trade union organizations), from the Sandinista Youth as well as from a number of FSLN activists. Moreover, a left-wing group of former members of the “prolonged people’s war” faction that published the bulletin Nicaragua Desde Adentro disapproved of Humberto Ortega’s decision to remain head of the army under a right-wing presidency instead of leaving his position to his deputy, who was also a member of the FSLN, so that Humberto Ortega could remain in the FSLN leadership and join the political opposition to the new regime.

A few months after Violeta Chamorro started her mandate as president, a massive movement spread throughout the country in July 1990, protesting massive layoffs planned in the public services as well as other issues linked with the implementation of a market-oriented economic policy. Managua and other cities were covered with Sandinista barricades and the trade unions launched a general strike. This resulted in a compromise with Violeta Chamorro’s government, which was forced to withdraw some measures, but the Sandinista grassroots was disgruntled at the FSLN leadership having halted protest actions. Later, the Front’s leadership gradually made concessions to Chamorro, accepting the dismantling of the public banking sector, the reduction of the public sector in both agriculture and manufacturing, the end of the State’s monopoly on foreign trade. Chamorro also organized the cleansing of the police force and incorporated former Contras into it.

It must be said that after the victory of the Right, a significant part of the estates formerly expropriated from the Somocistas after the 1979 victory were appropriated by a few Sandinista leaders, who consequently accessed to the role of capitalists. This process was called piñata. Those who organized it accounted for it as meeting the need to secure assets for the FSLN against a government that might want to confiscate the Party’s assets.

Despite a radicalization of some elements of the FSLN throughout 1990 and 1991, others such as former Sandinista minister Alejandro Martinez-Cuenca openly mentioned the need for a “co-gobierno,” a kind of conditional external support to Violeta Chamorro’s government, and supported the policy enforced by the International Monetary Fund, which to some extent could be perceived as in line with the policy followed by the Sandinista government from 1988. Éric Toussaint was a first-hand eyewitness to such class-collaborationist policies advocated for by Daniel Ortega and other FLSN leaders in 1992 as a participant in the 3rd Forum of São Paulo.

In Managua in 1992, Éric Toussaint accompanied Ernest Mandel, a leader of the Fourth International, who had been invited to deliver the inaugural speech at the 3rd Forum of São Paulo. The Forum, launched in 1990 by Brazil’s Workers’ Party (in Portuguese – Partido dos Trabalhadores – PT) under Lula da Silva’s leadership, brought together a broad spectrum of the Latin American Left, from the Cuban CP to the Frente Amplio of Uruguay and including guerrilla organizations like the FMLN in El Salvador.

Ernest Mandel entitled his speech “Socialism and the Future.” Beginning with an observation of the great difficulties facing the forces of the radical Left worldwide, he stated that priority had to be given to emphasizing demands aimed at attaining fundamental human rights, while at the same time maintaining the perspective of socialism. In his conclusion, he stressed that:

“This socialism must be self-managing, feminist, ecological, radical-pacifist, pluralistic; it must qualitatively extend democracy, and be internationalist and pluralist – including in terms of multiparty system. […] the emancipation of the workers will be the work of the workers themselves. It cannot be done by states, governments, parties, supposedly infallible leaders or experts of any kind.”

During the Forum, Víctor Tirado López, one of the commandants who were closest to Daniel Ortega at that time, asked to have a private meeting with Ernest Mandel, who asked Éric Toussaint to accompany him. Víctor Tirado López began by saying that he had much admiration for Ernest Mandel’s work, and in particular his Marxist Economic Theory. Then, the commandant expounded his analysis of the international situation: according to him, the capitalist system had reached maturity and would undergo no further crises, and would lead to socialism without the need for further revolutions. This was totally absurd, and Ernest Mandel said so very clearly and with emotion. When Mandel then responded that crises would indeed continue and that in certain parts of Latin America, such as Brazil’s Northeast, living conditions were clearly worsening for the most exploited populations, Tirado López answered that those regions had not yet been reached by the civilization that had been brought by Christopher Columbus five centuries earlier. Ernest Mandel and Éric Toussaint then put an abrupt end to this preposterous conversation.

The following day, Daniel Ortega expressed the desire to meet in private with Mandel to present the proposed alternative program he wanted to defend publicly as the FSLN against the rightist government of Violeta Chamorro. After reading it, we realized that the program did not meet the minimum conditions for constituting an alternative. To put it simply, it was compatible with the reforms undertaken by the rightist government and would not enable the offensive against the Right to be resumed. Mandel said so very clearly to Daniel Ortega, who was not at all pleased.

These two discussions show how profoundly certain FSLN leaders had gone astray. The subsequent evolution of Daniel Ortega and those who accompanied him on his path back to power was already clearly perceptible in the early 1990s.

Daniel Ortega’s Consolidation of Power Within the FSLN

A large part of the Sandinista militants from the revolutionary period rejected that orientation in the years that followed. It took time, and Daniel Ortega took advantage of the slow dawning of awareness of the danger to consolidate his influence within the FSLN and marginalize or exclude those who defended a different orientation. Simultaneously, Daniel Ortega succeeded in maintaining privileged relations with a number of leaders of popular Sandinista organizations who felt that in the absence of anyone else, he was the leader most likely to defend the series of gains made during the 1980s. That explains in part why, in 2018, the Ortega regime still has the support of part of the population and the popular movement despite its use of extremely brutal methods of repression.

Ortega’s consolidation of power within the FSLN in the 1990s is best summed up by Mónica Baltodano, former guerilla commander, former member of the FSLN leadership and now a member of the Movement for the Rescue of Sandinismo (in Spanish – Movimiento por el Rescate del Sandinismo – MpRS):

“The dispute within the FSLN between 1993 and 1995 [which culminated in a large number of professionals, intellectuals and others splitting away, many of them to form the Sandinista Renovation Movement (MRS), which is different from Mónica Baltodano’s MpRS that was founded later] persuaded Ortega and his iron circle of the importance of controlling the party apparatus. That became more concretized precisely in the FSLN’s 1998 Congress, in which what remained of the National Directorate, i.e. the Sandinista Assembly and the FSLN Congress itself, were replaced with an assembly whose participants were mainly the leaders of the grassroots organizations loyal to Ortega. Little by little even that assembly stopped meeting. At that point an important rupture occurred. By then it was already evident that Ortega was increasingly distancing himself from leftist positions and centering his strategy on how to expand his power. His emphasis was power for power’s sake.”

Mónica Baltodano goes on to explain the building of alliances that ultimately led to Daniel Ortega’s coming back to the presidential office:

“An alliance-building process started then to increase his power. The first was with President Arnoldo Alemán, which produced the constitutional reforms of 1999-2000. Ortega’s central aims in that alliance were to reduce the percentage needed to win the presidential elections on the first round, divvy up between their two parties the top posts in all state institutions [such as the Electoral Council, the Court of Auditors and the Supreme Court] and guarantee security to the FSLN leaders’ personal properties and businesses [acquired during and after the piñata]. In exchange, he guaranteed Alemán ‘governability’ by putting a stop to strikes and other struggles for grassroots demands. The FSLN stopped opposing the neoliberal policies. In the following years, the main leaders of the party’s once mass organizations became National Assembly representatives or were brought into the structures of Ortega’s circle of power. With that they obviously stopped resisting and struggling for all the things they had once believed in.

“Those years also saw the forming of ‘ties’ – I wouldn’t call it an alliance – with the head of the Catholic Church, Cardinal Obando. The main purpose of that linkage was control of the electoral branch of government through Obando’s personal, intimate relation with Roberto Rivas, who had been heading the electoral branch since 2000. It also bought Ortega increased influence with both the Catholic faithful and the church hierarchy.”

After Alemán was charged with corruption and sentenced to 20 years’ imprisonment, the agreement he had concluded with Ortega proved to be profitable: Ortega saw to it that the men he had placed in the judicial system arranged preferential treatment for Alemán, allowing him to serve out his sentence in house arrest. Later, in 2009, two years after his election as president of Nicaragua, Daniel Ortega gave his support to the Supreme Court’s decision to quash Alemán’s conviction and release him. A few days later Alemán returned the favor by ensuring that the parliamentary group of the Liberal Party he led voted for the election of a Sandinista at the head of the National Assembly.

The constitutional reforms of 1999-2000 reduced the percentage needed to win the presidential election on the first round to 35% of the votes if the candidate has a 5% margin over the candidate coming in second. Ortega was elected with 38.07% of the votes in November 2006 and took office in January 2007. He was re-elected in November 2011 and in November 2016, after what Rosario Murillo, whom he had married in the church with Cardinal Obando as officiant and who had been spokesperson of the government since 2007, became vice-president.

The Revolution Betrayed

Since 2007, the policies which have been implemented by Ortega and Murillo have looked more like a continuation of the policies pursued by the three right-wing governments that succeeded one another between 1990 and 2007 than like a continuation of the Sandinista experience from 1979-1990. In this respect, the article by Mónica Baltodano, published in January 2014 and quoted above, deserves a full reading.

In the last eleven years, Daniel Ortega’s government did not carry out any structural reform: no socialization of the banks, no new agrarian reform despite the very important concentration of land in the hands of big landowners, no urban reform in favor of the toiling classes, no tax reform in favor of more social justice. Free-trade zone regimes have been expanded. The contracting of internal and external debt has been pursued under the same conditions that favor the creditors through the interest payments they receive and that allow them to impose policies in their favor through blackmail.

In 2006, the Sandinista parliamentary group voted hand in hand with the right-wing MPs in favor of a law totally prohibiting abortion. It was under the presidency of Daniel Ortega, who refused to call the measure into question, that the prohibition was included in the new criminal code that entered into force in July 2008. There are no exceptions whatsoever to the prohibition, including cases of danger to the health or the life of the pregnant woman or pregnancy resulting from rape. This retrograde legislation was accompanied by serious attacks on organizations defending women’s rights, who have been among the most active in the opposition to the Ortega government. In another very troubling development, references to the Catholic religion have been systematically used by the regime, in particular by Rosario Murillo who has made a point of denouncing women’s rights organizations and the support they receive from abroad in their struggle for the right to abortion as being “the Devil’s work.”

In 2006, the Sandinista parliamentary group voted hand in hand with the right-wing MPs in favor of a law totally prohibiting abortion. It was under the presidency of Daniel Ortega, who refused to call the measure into question, that the prohibition was included in the new criminal code that entered into force in July 2008. There are no exceptions whatsoever to the prohibition, including cases of danger to the health or the life of the pregnant woman or pregnancy resulting from rape. This retrograde legislation was accompanied by serious attacks on organizations defending women’s rights, who have been among the most active in the opposition to the Ortega government. In another very troubling development, references to the Catholic religion have been systematically used by the regime, in particular by Rosario Murillo who has made a point of denouncing women’s rights organizations and the support they receive from abroad in their struggle for the right to abortion as being “the Devil’s work.”

Nicaragua can still be characterized by its very low wages. ProNicaragua, the official agency promoting foreign investment in the country, brags about “[t]he minimum wage [being] the most competitive at the regional level, which makes Nicaragua an ideal country to set up labour-intensive operations.” Over the recent years, labour insecurity starkly increased: informal economy represented 60% of the total employment in 2009, a figure which stood at 80% in 2017. No progress was made toward a diminution of social inequalities, and the number of millionaires increased. The growth in wealth produced was not distributed to the toiling classes but benefitted the big national and international capital, with the help of Daniel Ortega’s government. Furthermore, the latter and his family also became richer.

The main trigger of the social protests that started in April 2018 was the announcement by Ortega’s government of neoliberal measures to be taken concerning social security, in particular, pension reform. These measures were advocated for by the IMF, with which Ortega had maintained excellent relations since he took office in 2007. In a statement published in February 2018, the IMF congratulated the government for its achievements: “Economic performance in 2017 was above expectations and the 2018 outlook is favorable … Staff recommends that the INSS [Nicaraguan Social Security Institute] reform plan secures its long-term viability and corrects the inequities within the system. Staff welcomes the authorities’ efforts to alleviate INSS’ financing needs.”

The most unpopular measures were a 5% decrease of the pensions meant to finance medical expenses and a limitation of the annual indexation of these pensions over the inflation rate. Future pension benefits for the close to one million workers affiliated to the pension system were meant to be based on a less favorable calculation, which would have resulted in cuts in pension benefits that could have been as high as 13%.

These measures sparked a mass protest movement, at first mainly composed of students and young people. The movement quickly joined with other protests, in particular with the mainly peasant- and indigenous-based movement against the construction of a transoceanic canal meant as an alternative to the Panama Canal that would endanger large parts of the environment and livelihoods.

Eventually, Ortega gave up on these reforms. This was not before he had initiated a criminal spiral of repression which resulted in more than 300 protesters being killed by security forces and pro-regime militiamen. Now joined by parts of the population horrified by the government’s repressive response, the protests radicalized, eventually demanding the fall of the regime.

The government accused the protesters of being right-wing “golpistas” and “terrorists” working toward regime change with the support of U.S. imperialism. The government was, however, unable to provide any non-fabricated evidence to support such claims. In fact, the United States, which has little to say about Ortega’s neoliberal economic policies, took rather timid sanctions in reaction to the repression so far. Similarly, the examination by the U.S. Senate of the Nicaraguan Investment Conditionality Act (NICA) of 2017, which deserves to be denounced as an imperialist policy impinging on Nicaragua’s national sovereignty, was not sped up during the events of Spring 2018; it finally passed the Senate as late as end of November 2018 and became a law on 20 December 2018.

Furthermore, Ortega and Murillo strengthened their use of religious fundamentalist references and denounced the protesters as having “Satanic” rituals and practices, as opposed to the rest of the Nicaraguan people, “because the Nicaraguan people are God’s people!” On 19 July 2018, during the rally organized on the anniversary of the Sandinista revolution to try and strengthen his legitimacy, Ortega repeated these absurd claims and called on the Catholic bishops to exorcize the protesters and chase out the devil which supposedly had taken possession of them.

By the middle of July, the policy of terror led by the government allowed the latter to regain control of the streets. Since then, massive arrests have taken place and several hundreds of people, labelled as “terrorists” by the government, are still imprisoned. Human rights associations are not permitted to enter the prisons, nor are the lawyers of some of the detainees. Some of them were tortured and forced to give false confessions supporting the claim according to which the regime faces a foreign-led plot aimed at removing it by force.

By Means of Conclusion

The Sandinista revolution started as an extraordinary experience of social liberation and renewal of national dignity in a dependent country whose status as a backyard for U.S. imperialism had been accepted by its authoritarian, dynastic rulers for decades. The achievements of the Sandinista government between 1979 and 1990, however, did not go far enough. While they allowed for significant improvements of the living conditions of most of the Nicaraguans, they did not break with the export-oriented extractivist model, which was dominated by the big capital, nor did they significantly promote the active participation of the masses in the economic and political decision-making processes. The political institutions and the internal organization of the FSLN were not developed as tools that could have empowered the masses, an error which allowed for the FSLN degeneration during Ortega’s road back to power.

This understanding of the Nicaraguan revolution and its degeneration stresses the need for revolutionaries and socialist activists to encourage the broadest possible participation of the masses in the fight for their emancipation, as well as to help ensure their self-organization. A corollary to this idea is the need for revolutionaries to struggle against the bureaucratization of their organizations’ leadership – which begins with building organizations that respect internal democracy. This was strongly underestimated by the FSLN, which remained a political-military organization after it had seized power and waited until 1991 before it organized its first congress as a political organization. While the Sandinista leadership made the right choice when it recognized the victory of the Right in 1990, the subsequent steps taken by the FSLN leadership under Daniel Ortega were clearly meant for him to come back to power for power’s sake. The left-wing of the FSLN, which organized as critical currents during the 1990s, was too timid in its opposition to these moves.

Finally, the international Left needs to have a materialist analysis of social and political processes, and shall not cling to fantasized ideas of experiences of really existing socialism. The evolution of the FSLN and the policies led in Nicaragua since 2007 should be analyzed for what they are rather than on the basis of what Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo presumably stood for as FSLN activists during the 1970s and 1980s. In this sense, Ortega and Murillo’s deepening of the neoliberal policies pursued by their right-wing predecessors, as well as their total ban of abortion should be denounced by the international Left. Furthermore, the Left should strongly denounce the criminal repression currently organized by the regime against protesters and demand the immediate release of all political prisoners. When adopting such a stance, the Left should in no way compromise itself by supporting a right-wing, pro-imperialist opposition. On the contrary, this stance should be accompanied by an effort to link with and reinforce the critical Sandinistas and other members of the progressive opposition to Ortega and Murillo, in particular the youth who mobilized strongly since April 2018, the feminist movement, and the peasant and indigenous movement who opposed the project of transoceanic canal and other destructive projects linked with the export-led capitalist model. •

This article first published on the International Viewpoint.org website.