Politicizing Public Transit in Toronto

According to the Toronto Star, the reason why the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) is in such a lackluster state is because of “politics trumping sound transit planning.” Wouldn’t it be great, the Globe and Mail asks us to wonder, “if we could get politics out of public transit?” Yes, answers the Torontoist, it really would be great: “Politics should be removed from transit planning.” So, follows up the activist group Scarborough Transit Action, “How do we get the politics out of transit planning?”

The sway of politics in transit policy is blamed for incentivizing vote-chasing behavior. Instead of relying on expertise and evidence to arrive at decisions about transit infrastructure, those who occupy Toronto City Hall and Queen’s Park base their decisions on the need to attract voters. This is why everyone from the Ford brothers to Kathleen Wynne and John Tory eventually got behind the $3.35-billion 1-stop Scarborough subway. Even the federal government agreed to help fund the wasteful project.

The sway of politics in transit policy is blamed for incentivizing vote-chasing behavior. Instead of relying on expertise and evidence to arrive at decisions about transit infrastructure, those who occupy Toronto City Hall and Queen’s Park base their decisions on the need to attract voters. This is why everyone from the Ford brothers to Kathleen Wynne and John Tory eventually got behind the $3.35-billion 1-stop Scarborough subway. Even the federal government agreed to help fund the wasteful project.

It’s no surprise, then, that transit activists are being won over to the idea that politics should be sidelined in transit policy discussions. Many have come to believe that if only transit experts were allowed to do their jobs without interference from vote-seeking politicians, an evidence-driven transit policy could be adopted and Toronto could build the kind of world-class transit system it deserves.

Evidence-Based Decision Making

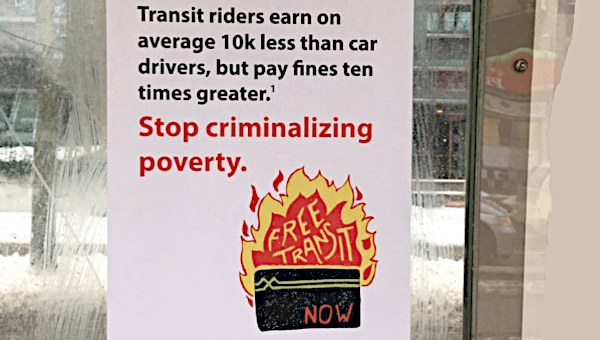

Attractive as such an outlook may seem, transit activists should be wary of buying into it. The truth is we need more politics, not less, in order to address Toronto’s transit woes. That political elites can toy with transit policy for the purpose of vote-seeking is not an indication that the issue of public transit is burdened by an excess of politics. Rather, it shows that there is a lack of substantive political engagement with the issue, including a lack of an informed citizenry that has the opportunity and capacity to participate in transit policy discussions.

Far from being a hindrance to evidence-based decision making, politics is the best means to achieve it. A lively political sphere can bring together expert advice, data and scientific projections, as well as discussion on the needs and experiences of residents to arrive at informed transit policy decisions. This is, anyhow, what historical experience shows.

Consider, for instance, the case of 1970s Bologna, a city in northern Italy, where substantive political engagement helped to bring about radical reforms to public transit. Over the course of a two-year period, neighborhood “traffic committees” brought together residents, transit experts, and political representatives to design and implement reforms to the city’s public transit:

“In spring 1972, hardly an evening passed without debates in some assembly hall somewhere between workers and students, shop owners and housewives, on Bologna’s traffic future… Scientific surveys of the volume of traffic in the city and of the behavior of the people involved in traffic, measuring of noise levels and air pollution played an equal part in the process.”1

The result was the creation of an urban environment far less dominated by the private automobile, meaning there was less congestion, less pollution, and fewer accidents. On streets where children played, car traffic was limited or banned completely. What’s more, a partially-free, wide-reaching public transit network was put into place.

In Bologna, it was openly recognized that “every traffic question has a political side too.”2 Transit issues were seen as inherently political not only in the sense that they required active public engagement, but also because transit policy was seen as a terrain of political contestation. It was understood, for instance, that car manufacturers had an interest in derailing the creation of a well-functioning public transit system.

No Politics-Free Zone

In Toronto, those who say that politics has no place in transit planning seem to have dreamed away the contested nature of transit policy. If we’re serious about reforming transit in this city, we don’t have the luxury to engage in this sort of dreaming. There’s no politics-free zone where beautiful, picturesque, evidence-based transit policy roams and thrives.

To believe that there is means falling for a trap the political elite have set for us. According to them, there is such a politics-free zone: it’s called the market. The impoverishment of the political sphere in Toronto is such that even our politicians want to pretend that they’d rather not engage in politics. And selling off our transit assets and services to profiteering firms is, apparently, the most apolitical of all possible things.

Rather than trying to depoliticize transit policy, transit activists have to push for the opposite. We have to take up the task of building an active political sphere in which rational discussion can take place and evidence-based decision making can happen. This means that transit activists have to become organizers. We have to build institutions that allow regular people to engage with transit issues and develop their capacities. And, ultimately, we have to organize to win power in City Hall and Queen’s Park – because if the political elite would rather not engage in politics, we’ll have to do it instead. •