Ontario Election 2018: Right-Wing Populism Prevails Over Moderate Social Democracy

In the June 7 provincial election, Ontario politics took a sharp turn to the right as the Progressive Conservatives (PCs), under the leadership of the populist businessman and former Toronto city councillor Doug Ford, steamrolled to a majority government. The PCs took 40.5 per cent of the popular vote and 76 out of 124 seats in the Ontario legislature, putting an end to the 15-year reign of the Ontario Liberals. The Ontario New Democratic Party (NDP), under the leadership of Andrea Horwath, catapulted from their third-place position to Official Opposition, and received 33.6 per cent of the popular vote and 40 seats. Meanwhile, Premier Kathleen Wynne and the Liberals suffered a catastrophic defeat, receiving just 19.6 per cent of the popular vote and 7 seats – one seat below the threshold for official party status in the legislature.

The PCs last won an election in Ontario in 1999, when the right-wing government of Mike Harris – whose ‘Common Sense Revolution’ included large tax cuts, ‘workfare’, the weakening of trade unions and deep cuts in public spending – was re-elected with a second majority. By the 2003 election, however, the tide had turned strongly against the Tories and the party spent the next 15 years in opposition. During this period, the party was divided between those that wished to continue the Harris approach and those that sought to move closer to the political centre. In the most recent election in 2014, PC leader Tim Hudak, a right-wing ideologue, flirted with ‘right to work’ laws and promised to take the Common Sense Revolution further. His One Million Jobs Plan that called for the elimination of 100,000 public sector jobs in order to eliminate the province’s deficit, as well as the slashing of corporate taxes by 30 per cent in order to attract investment. Offering voters little more than hyper-austerity, the Tories again went down to defeat.

The PCs: The Triumph of Right-Wing Populism, Ontario Style

In the May 2015 leadership race, federal Conservative MP Patrick Brown prevailed over PC MPP and deputy leader Christine Elliott. In spite of Brown’s own socially conservative voting record and support from social conservatives in his leadership run, Brown quickly changed course and set out to remake the PCs as a socially liberal, centrist party that rejected ideological polarization and sought to govern for all Ontarians. In November 2017, Brown released his program, the “People’s Guarantee,” a rather centrist document that included a carbon tax and left much of the Liberal legacy in place.

With the Tories enjoying a wide lead in the polls as they headed into the election, Brown appeared well poised to be the next Premier of Ontario. However, Brown was forced to resign as leader in January in the wake of sexual harassment allegations. This led to another leadership contest that took place in March. In addition, Brown was accused of misappropriating party funds.

In announcing his leadership bid, Doug Ford stated that “I can’t watch the party I love fall into the hands of the elites.” Ford prevailed over ‘establishment’ candidate Christine Elliott, who had the support of most of the PC caucus. While narrowly losing the popular vote to Elliott, Ford won the leadership race due to a points system that weighted votes by riding.

The son of the late Doug Ford Sr., a Harris era MPP and founder of Deco Labels, a multimillion dollar company with operations in Canada and the USA, Doug Ford is a co-owner of the family business and has continued the family tradition of right-wing politics. He was also seen as the brains behind his brother, the late Rob Ford, the infamous mayor of Toronto elected on populist pledges of “respect for taxpayers,” stopping the “gravy train” at City Hall and ending the “war on the car” who later brought notoriety to Toronto worldwide when videos emerged of him smoking crack. Doug Ford entered politics in 2010 and was elected in the low income, multicultural ward in north Etobicoke that had previously been represented by his brother. Doug Ford acted as the ‘co-mayor’ of Toronto during his brother’s mayoralty, and stepped in to run for mayor when his brother received a cancer diagnosis. Ford lost the mayoralty race to the establishmentarian conservative John Tory, but received 34 per cent of the popular vote and carried the working class wards on the city’s periphery.

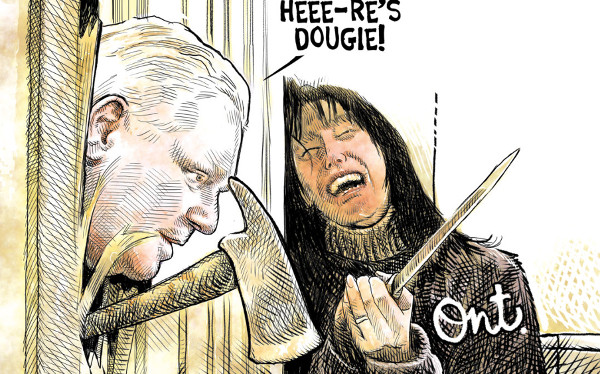

As a wealthy businessman who rails against the “elite,” Ford has inevitably drawn comparisons to U.S. President Donald Trump. While Ford had previously expressed strong support for Trump, he later rejected the comparison and dismissed it as a media fabrication. Like Trump, he is known for his refusal to be ‘politically correct’, denigration of expertise, hostility to the press and bullying behavior. Ford also has a long track record of misogyny. Yet in contrast to Trump and other right-wing populists, racism and xenophobia have not been a central component of Ford’s campaign messaging and Ford has received significant support in many ethnic and immigrant communities (in spite of his past links to, and continued support from, far-right circles).

In his pitch for the leadership, Ford spoke of his key role in his brother’s administration, making the dubious claim of having saved Toronto taxpayers $1-billion. He offered the PCs the ability to win seats in the city of Toronto, where the party had been more or less shut out since 2003 (though former city councillor Raymond Cho was elected as a PC MPP in a Scarborough riding in a 2016 by-election), as well as an ability to appeal to disaffected Liberal and NDP voters, blue collar workers and “populists” across the province.

With Brown out of the picture, the “People’s Guarantee” was declared null and void by all of the leadership candidates, with Ford leading the charge. Appealing to the right-wing base of the party, Ford railed against the implementation of a carbon tax and vowed to scrap the province’s cap-and-trade system (“cap the carbon tax and trade Kathleen Wynne”). And in an appeal to social conservatives, Ford pledged to “stand for parents” and repeal the province’s sex-ed curriculum (“Sex ed curriculum should be about facts, not teaching Liberal ideology”). Upon winning the leadership race, Ford declared that: “The party is over with the taxpayers’ money.”

Ford simplified the PC Party message (and laid it out under the sly platform title, For the People: A Plan for Ontario). Freeze the minimum wage at $14 an hour and instead eliminate the provincial income tax on incomes below $30,00 in order to provide relief to low-income workers. A 20% income tax cut for the ‘middle class.’ Cut the corporate tax rate from 11.5% to 10.5% in order to make Ontario ‘open for business’ and attract jobs. Lower gas prices by 10 cents a litre by cutting the provincial fuel tax and fight the implementation of any carbon tax by Ottawa. Respect the will of parents over ‘special interests’ and replace the sex education curriculum. Lower hydro prices by firing the CEO of Hydro One (“the six million dollar man”) and its board of directors.

In contrast to Hudak’s “100,000 jobs” pledge, Ford vowed that there would be no layoffs under his watch (“Let me be clear: No one is getting laid off”). Rather he would eliminate government waste simply by finding $6-billion in unspecified “efficiencies.” According to Ford, given the fiscal recklessness of the Liberal government, this was a modest goal that could easily be achieved. As he put it in the first leaders’ debate: “When I tell people, ‘My friends, we will find four cents on every dollar of efficiencies,’ they break out laughing. ‘That’s all you can find is four cents in efficiencies?’” In addition, Ford promised to balance the budget within his first term in office.

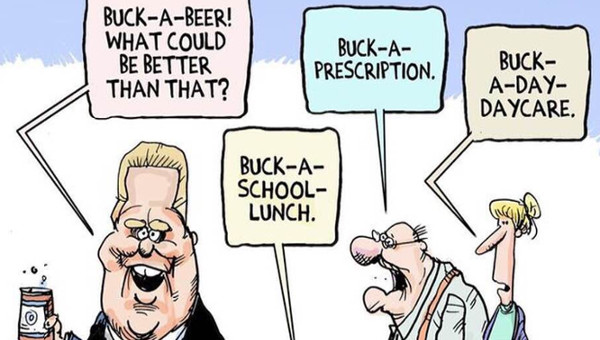

Ford was repeatedly questioned by his opponents and the media as to how specifically he would find ‘efficiencies’ without cuts to jobs and public services, but he repeatedly dodged the question, stating only that a costed platform would appear before June 7. The PCs released a partially costed platform just days before voting day (but not before promising “a buck a beer back to Ontario” – meaning it was legal for brewers to sell at that price).

An analysis of party platforms by economist Mike Moffat found that the PCs were the furthest away from a balanced budget among the parties. According to Moffat: “The promises add up to about $7-billion a year in tax cuts and spending. And it’s not clear where that $7-billion is going to come from.”

In addition to the lack of a costed plan, other controversies dogged the campaign, but they had little impact on the final result. For example, more than one quarter of PC candidates faced lawsuits or police investigations. And three days before the election, Rob Ford’s widow Renata Ford, filed a lawsuit against Doug Ford, alleging that he had mismanaged the family business and cheated Rob Ford’s family out of their inheritance.

Ford received a lukewarm reception in Ontario’s elite sectors, which would have preferred a smoother delivery from a more ‘generic’ conservative. The Globe and Mail, the main voice of the business establishment, refused to endorse its traditional party choice under Ford’s leadership. However, like the ‘never Trump’ movement among certain ‘establishment’ Republicans in the U.S., the impact was virtually nil.

While the PCs had a comfortable lead in the polls at the beginning of the campaign, Ford was seen as a liability to the party brand. The party’s decision to not have a media campaign bus was widely seen as a move to avoid media scrutiny. What looked like a cake-walk soon turned into a neck-in-neck race with the NDP. However, the PCs pulled ahead in the last days of the campaign, benefitting from anti-Liberal sentiment in the province and a sizable constituency of fiscal and social conservatives.

The Liberals: Out of the Game

In their 15 years in office, the Liberals have pursued an approach of ‘progressive competitiveness.’ While implementing some progressive social policy reforms during their tenure, such as full-day kindergarten, this was all done within in a broader framework of keeping Ontario ‘competitive.’ Corporate taxes were kept low, and Ontario maintained the lowest level of per capita spending among the provinces. The Liberals also showed a strong affinity for the use of private-public partnerships for financing investments in hospitals, transit and other infrastructure.

Kathleen Wynne was elected to the leadership of the Ontario Liberal Party and became the Premier of Ontario in January 2013. A former school trustee who entered politics to fight Harris cuts to education, Wynne was first elected as a Liberal MPP in 2003 and went on to serve in several Cabinet portfolios in the government of Dalton McGuinty. The first woman premier of Ontario and the first openly gay premier of any province, Wynne was seen as a left-wing Liberal and expressed a desire to be remembered as the ‘social justice premier’.

In the October 2014 election, the Liberals reversed course from the austerity-focus of the McGuinty governments and campaigned on progressive planks such as taxing the rich, the establishment of an Ontario pension plan, and deficit financing to pay for major investments in transit and infrastructure. While the Tories staked out territory on the hard right, Wynne presented herself as a champion of activist government. The Liberals outflanked a rightward-shifting NDP on the left, which desperately sought to present itself as a party of fiscal responsibility. The ‘bury the NDP’ strategy proved successful, and the Liberals also benefitted from a ‘stop Hudak’ campaign led by the province’s unions. Wynne was able to overcome the scandals of the McGuinty era and led the Liberals to a majority government.

A year later, however, Wynne’s controversial decision to sell off a majority stake of the province’s publicly-owned electrical utility, Hydro One, in order to pay for infrastructure improvements, marked a turning point for her government. The Toronto Star provincial affairs columnist Martin Regg Cohn described it as “the biggest miscalculation of Kathleen Wynne’s time as premier.” The privatization was opposed by over 80% of the population, and Ontarians associated the privatization with skyrocketing electricity bills. And, despite the election’s progressive tones, Wynne governed in her first years in office with the same budget austerity as McGuinty and adopted the infamously neoliberal Drummond report as her policy reference.

But in her last year in office, Wynne again – and confusingly – shifted leftward. While previously lukewarm to the idea of raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour, Wynne soon gave into pressure from the “15 and Fairness” campaign. In May, Wynne announced that the province’s minimum wage of $11.40 an hour would be significantly increased, rising to $14 an hour in January 2018 and again (if the Liberals were re-elected) to $15 in January 2019. The Liberals also implemented changes to Ontario’s labour laws, including card check union certification in certain sectors and supports for temporary workers and some measures to support equal pay for equal work. The Liberals also introduced a pharmacare program for all Ontarians under the age of 25, OHIP+.

In their election budget, the Liberals unveiled a universal childcare program for children aged 2.5 until the start of kindergarten that was widely praised by childcare advocates. It also called for investments in healthcare, mental health and transit. After achieving a modest surplus in 2017-18, the Liberals would return to deficit spending, with a projected six years of deficits. With the slogan “Care Over Cuts,” Wynne and the Liberals sought a repeat of the 2014 election strategy of marginalizing the NDP and presenting themselves as the progressive choice in a two-way race with the Conservatives.

The bump the Liberals received in the polls from the budget soon evaporated. With Wynne’s personal unpopularity and around 80 per cent of Ontarians wanting a change in government, the Liberals fell to third place.

While continuing their attacks on Ford and the Conservatives (“Doug Ford sounds like Donald Trump and that’s because he is like Donald Trump”), the Liberals soon turned their guns on the rising NDP as well. In a meeting with the Toronto Star editorial board, Wynne defended her record, stating that “We really, I believe, run the most progressive government in North America.” While maintaining that the Liberals and NDP shared “similar values,” the Liberals embraced “practical solutions” and did not “let ideology get in the way.” Wynne continued to attack the NDP for being too ideological and too beholden to unions.

In a stunning announcement on June 2, Wynne conceded that: “After Thursday, I will no longer be Ontario’s premier.” Conflating Ford and the NDP as equally risky, Wynne called for the election of as many Liberal MPPs as possible to block a majority government. Wynne maintained that voting Liberal would prevent either party from “acting too extreme” and from having a “blank cheque.”

Given her reputation as a progressive Liberal, it is difficult to believe that Wynne truly believed that an NDP government would be just as bad as a Ford one. However, an NDP victory was more likely to solidify their hold on the centre-left that the Liberals had traditionally occupied and prevent the Ontario Liberal Party from ever recovering. Wynne put the future of her party over the good of Ontario.

The NDP: The Orange Wave Fizzles

Andrea Horwath, a community organizer and city councillor in Hamilton before being elected as an MPP in 2004, has served as the leader of the Ontario NDP since 2009. Under Horwath’s leadership, the NDP, which had spent more than a decade in the political wilderness following the defeat of the unpopular government of Bob Rae in 1995, began to regain traditional levels of support.

Under Horwath, the NDP moved further away from traditional social democratic ideology. In the 2011 election, the party cracked 20 per cent for the first time since 1995, receiving 22.7% of the popular vote and 17 seats. The NDP showed further momentum by then picking up seats in four by-elections in Southwestern Ontario and Niagara region.

Rejecting what many saw as a fairly progressive budget, Horwath pulled the plug on the minority Liberals and forced an election in 2014. The NDP further alienated many of its traditional supporters and ran a populist campaign that positioned themselves to the right of the Liberals. Two of their central policy planks called for a Ministry of Savings and Accountability to find waste in government and tax cuts for small business. The NDP saw its popular vote increase modestly by 1 percentage point and took 21 seats, the same as before the election. The NDP picked up three seats elsewhere in the province, but three Toronto MPPs went down to defeat in an election that seemed to offer little for urban voters. Furthermore, the NDP now had less influence in the legislature as the Liberals went from minority to majority government.

In spite of the wounds of the 2014 election, Horwath made her peace with her critics in the party and easily survived a leadership review. Horwath shifted leftward in her rhetoric and promised to listen more closely to the party grassroots. In April 2016, the NDP belatedly came out in support of a $15 minimum wage, after previously rejecting such calls from activists in order to secure support from small business.

Seeking to avoid a repeat of the last campaign where they were outflanked on the left by the Liberals, the 2018 election platform, “Change for the Better,” moved closer to traditional social democratic positions. It focused on five key themes: (1) drug and dental coverage for all Ontarians; (2) end hallway medicine and fix seniors’ care; (3) cut hydro bills by 30% by bringing Hydro One back into public ownership; (4) take on student debt by converting loans to grants; and (5) making corporations and the wealthy pay their fair share.

“Change for the Better” moved away from the fiscal conservatism of the previous campaign, and run deficits over five years (though smaller than those of the Liberals). New revenues would come from increased personal taxes on incomes above $220,000 and an increase in the corporate tax rate to 13%. It included several positive reforms such as the end of police carding, covering 50% of municipal transit costs, and making it easier for workers to form unions. And certainly the calls for expanded social provision were welcome.

Yet however ‘bold’ the platform may have seemed compared to last time, many of the measures were very modest. The NDP’s childcare plan, for example, offered free childcare for families earning less than $40,000 and above childcare would average $12 a day based on income. Traditionally social democrats have prioritized universality in social programs rather than means testing. The dental plan was a complicated array of requiring employers to provide dental benefits and the establishment of a means-tested government benefit plan. The pharmacare plan would only cover 125 ‘essential’ drugs, with no specified timeline or plan on how to expand from there.

Considering the effort under Horwath to move the party to move to the political centre and present the NDP as a ‘government in waiting’, a surprising aspect of the campaign was that many of the party’s candidates had strong activist backgrounds. And there was more enthusiasm on the Left for the NDP in this election than there was in a long time. Activists that were traditionally skeptical of parliamentary politics, such as Rinaldo Walcott and Naomi Klein, as well as Desmond Cole, came out unequivocally in support of an NDP government to block a Ford government.

Horwath performed well in the first leaders’ debate, where she spoke strongly out against Ford’s claim to find ‘efficiencies’ (“efficiencies actually are cuts and people will pay the price in different ways”). The NDP soon pulled ahead of the Liberals, and by mid-May the NDP was neck-in-neck with the Conservatives. It seemed very possible indeed that the NDP could form the government. The Liberals were on the decline and among Liberal voters, an overwhelming majority had the NDP as their second choice over the PCs led by the polarizing Ford.

With its rise in the polls, the NDP came under greater scrutiny. An accounting error in the NDP platform meant that a projected $3.3-billion deficit in their first year was in fact $4.7-billion. While the NDP still had smaller deficits than those of the Liberals (and almost certainly the PCs!), this likely hurt their attempt to assure skeptics that an NDP government would be ‘fiscally responsible.’ The NDP also came under virulent attack from the Conservatives and the right-wing tabloid Toronto Sun (and similar papers across the province) that essentially served as an arm of the Ford campaign, with a focus on the “radical activists” who made up the party’s candidates (needless to say there was no mention of extreme right-wing candidates such as Andrew Lawton in London). And not surprisingly, the specter of the Rae government was raised, with Ford warning that an NDP government would “annihilate the middle class” and “bankrupt this province” and would be “ten times worse than the Liberals.

Horwath distanced herself from Rae (“We’re in 2018 now. This is not 1990.”). She came out strongly in defence of the NDP’s ‘radical’ candidates. She also strongly defended public sector collective bargaining rights in the face of attacks on the NDP’s ‘rigid’ opposition to the use of back-to-legislation (“It’s a pretty heavy hammer… it’s very much against our values”), and placed the blame for strikes in the postsecondary education sector squarely on the lack of government funding.

With the Liberals out of contention, many traditional Liberal voters turned to the NDP to stop Ford. The NDP received a key endorsement from the Toronto Star, the province’s largest circulating newspaper, which traditionally backs the Liberal Party.

In spite of the NDP’s rise in the polls, the party hardly galvanized Ontarians. While many voters were willing to give the NDP a chance, this support was soft and largely had to do with exhaustion with the Liberals, Horwath’s personal likeability and the deep unpopularity of Wynne. With a more popular program and inspiring campaign, the NDP may have been able to better deflect the attacks from the right, but instead they just seemed to feed the ‘not ready to govern’ narrative. The NDP was unable to dislodge enough residual support for the Liberals. Furthermore, the anti-Liberal narrative that developed over the past few years was mostly a right-wing one about bloated government and wasteful spending. The NDP had spent much of the Wynne period aiding this narrative rather than challenging it, and was unable to develop in such short time a compelling critique of the government from the left.

A Conservative Majority

The map of Ontario on election night was almost entirely blue and orange (see Table 1).

| Table: 1 | Seat Count by Region | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC | NDP | LIBERAL | GREEN | |

| Toronto | 11 | 11 | 3 | – |

| 905 Belt | 26 | 4 | – | – |

| Hamilton-Niagara | 2 | 7 | – | – |

| Southwestern Ontario | 15 | 8 | -1 | |

| Eastern Ontario | 11 | 2 | 3 | – |

| Central Ontario | 8 | – | – | – |

| Northern Ontario | 3 | 8 | 1 | – |

| ** Total (124) ** | 76 | 40 | 7 | 1 |

The PCs were able to obtain the majority by dominating suburban ridings across Ontario, particularly in the crucial Greater Toronto Area, adding to their traditional rural and small-town base. The NDP retained their traditional strongholds with a history of industrial trade unionism and class-based voting, and made significant gains in urban centres across the province. With the PC vote rising across the province, virtually all of the NDP pickups were in Liberal-held ridings (with the remainder being new ridings in an expanded legislature). The NDP came within 1,000 votes of defeating the Conservative candidate in 7 ridings (see Table 2). The Liberals, meanwhile, were wiped off the map outside of Toronto, Ottawa and Northern Ontario.

| Table 2 | Ridings where the NDP came within 1,000 votes of victory | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC | NDP | LIBERAL | Win Margin | |

| Ottawa West-Nepean | 16,591 | 16,415 | 14,809 | 176 |

| Sault Ste. Marie | 13,498 | 13,084 | 3,199 | 414 |

| Brampton West | 14,951 | 14,461 | 7,013 | 490 |

| Brantford-Brant | 24,080 | 23,459 | 5,439 | 621 |

| Kitchener-Conestoga | 17,005 | 16,319 | 6,035 | 686 |

| Kitchener South-Hespeler | 16,510 | 15,741 | 6,335 | 769 |

| Thunder Bay-Superior North | 5,395 | 11,154 | 11,973 | 819 |

| Scarborough-Rouge Park | 16,224 | 15,261 | 8,785 | 963 |

In the city of Toronto, the NDP and Conservatives each won 11 seats out of 25 seats and the Liberals held out in three. The NDP swept the 8 ridings that make up the progressive, but increasingly gentrified city core, including the new, affluent riding of University-Rosedale and the previously ‘safe’ Liberal ridings of Toronto Centre and St. Paul’s (both of which had been vacated by their incumbents). This was a sharp contrast to the 2014 campaign where the NDP underperformed among urban progressives. This time, inner Toronto saw some of the strongest swings from the Liberals to the NDP (see Table 3).

| Table 3 | NDP vote in selected ridings that changed from Liberal to NDP and change from 2014 | |

|---|---|---|

| Toronto Centre | 53.7% | +34.2 |

| Ottawa Centre | 46.1% | +25.6 |

| Toronto-St. Paul’s | 36% | +25.5 |

| University-Rosedale | 49.7% | +25.4 |

| Spadina-Fort York | 49.7% | +23.0 |

| Scarborough Southwest | 45.5% | +21.9 |

| Davenport | 60.3% | +20.1 |

| Hamilton West-Ancaster-Dundas | 43.2% | +18.3 |

| London North Centre | 47.6% | +17.6 |

| Kitchener Centre | 43.4% | +16.6 |

Meanwhile, the PCs took most of outer Toronto, winning ‘Ford Nation’ ridings in Scarborough and the city’s northwest and ridings that voted for John Tory municipally (such as Etobicoke-Lakeshore and Willowdale). In some ‘Ford Nation’ ridings (such as Scarborough North, represented by incumbent Raymond Cho and Ford’s own riding of Etobicoke North), the PCs received over 50% of the vote. Yet not all ‘Ford Nation’ ridings went PC. The NDP picked up three working class ridings (Scarborough Southwest, York South-Weston and Humber River-Black Creek) where they traditionally had a solid base of support but had been won by Ford municipally (and the NDP also came within 1,000 votes of winning in the new riding of Scarborough-Rouge Park which was strong territory for Ford municipally), while the popular Liberal Cabinet minister Mitzie Hunter narrowly prevailed in her riding of Scarborough-Guildwood. Kathleen Wynne narrowly held on to her riding of Don Valley West (the wealthiest riding in the province and one of the weakest areas for Ford municipally), while another popular Liberal Cabinet minister, Michael Coteau, was re-elected in neighbouring Don Valley East.

While the Liberals had won most of the suburbs of the ‘905’ belt that surrounds Toronto in 2014, this time the Liberals were shut out. The PCs won 26 out of 30 seats in this area and swept Mississauga, York and Halton Regions and all but one seat in Durham Region. The affluent northern suburbs of York Region swung especially hard toward the Conservatives, where they received over 50% of the vote. The working class, multicultural suburb of Brampton – bolstered by a beachhead established by federal NDP leader Jagmeet Singh in his election as an MPP in 2011 – represented an exception to Conservative dominance of the 905 region, with the NDP taking three out of its five seats (and came less than 500 votes short in a fourth). The NDP also held onto a seat in the working class city of Oshawa, albeit by a much reduced margin.

The NDP dominated the Hamilton-Niagara region, which includes Horwath’s home city and is an area with a long-standing tradition of working class support for the ‘labour party.’ The NDP picked up St. Catharines – where Liberal MPP Jim Bradley, the longest-serving member of the legislature, went down to defeat – as well as the middle class seat of Hamilton West-Ancaster-Dundas.

Southwestern Ontario was marked by an urban/rural split, with the NDP maintaining the traditional labour stronghold of Windsor and expanding their reach in London and Kitchener-Waterloo, and the PCs sweeping the rural and ‘rurban’ seats. While the NDP under Horwath has put much effort into winning Southwestern Ontario, the party’s gains in the region were modest, picking just up one seat each in the urban centres of London and Kitchener (though the NDP also came within 1,000 votes in two other Kitchener area seats). Fordian populism resonated with many working class voters in the region. The Conservatives picked up Cambridge and Brantford (albeit by just over 600 votes over the NDP in the latter), and easily defended seats such as Sarnia-Lambton that were targeted by the NDP. Another notable development in Southwestern Ontario was the election of Green Party leader Mike Schreiner in Guelph, giving the Greens representation at Queen’s Park for the first time.

In Eastern Ontario, the PCs, to nobody’s surprise, swept the traditionally conservative rural areas. They also made modest gains in the Ottawa area where they won 4 out of 8 seats. The Liberal vote held up stronger in the National Capital Region than anywhere else in Ontario, and three incumbent MPPs were re-elected (the ridings of Ottawa-Vanier and Ottawa South were the only ridings in the province that the Liberals won by more than 10 percentage points). In Ottawa Centre, socialist candidate Joel Harden defeated the province’s Attorney General, Yasir Naqvi, in a stunning upset (the NDP also came within 200 votes of the PCs in the riding of Ottawa West-Nepean). Another gain for the NDP in Eastern Ontario was the ‘university town’ of Kingston, a longtime Liberal stronghold.

The PCs swept the ‘cottage country’ region of Central Ontario, a traditionally conservative stronghold. The NDP won most of the seats in Northern Ontario, a region with a history of class politics and industrial trade unionism. It took two new ridings of Kiiwetenoong and Mushkegowuk-James Bay, established in the north to serve First Nations and francophone communities, and also gained the seat of Thunder Bay-Atikokan from the Liberals (by a margin of 81 votes!) However, the NDP lost its hold in the open seat of Kenora-Rainy River, where former federal Conservative Cabinet minister Greg Rickford was elected.. The PCs also narrowly prevailed over the NDP in Sault Ste. Marie (by 414 votes), a seat they took in a by-election last year. The Liberals narrowly hung on in the riding of Thunder Bay-Superior North (with the NDP losing by just over 800 votes).

The Ford electoral coalition thus included the traditional Tory base in rural and small-town Ontario, affluent suburbanites and much of the working class, as well as significant support from immigrant and racialized communities in the GTA. The NDP pulled together a cross-class coalition that comprised of a sizeable number of highly educated, ‘liberally minded’ professionals in urban centres and much of the ethnically diverse ‘new’ working class, in addition to their traditional working class and union base.

It is important to stress that a majority of Ontario voters oppose Ford and cast votes for more progressive parties. However due to the workings of the ‘first-past-the-post’ (or single-member plurality) electoral system, the Conservatives prevailed in a majority of the seats. The PCs clearly benefitted from vote-splitting between the NDP and Liberals. In 20 ridings alone, the combined NDP and Liberal vote exceeded that of the PC winner by a margin by at least 5,000 votes.

Challenging Ford’s ‘Populist Austerity’

Ford was sworn in as Premier on June 29. His slimmed down 21-member Cabinet includes the right-wing Vic Fedeli, who served as the party’s interim leader after the departure of Patrick Brown, as Finance Minister. Ford’s main leadership rival, Christine Elliott, was appointed as Deputy Premier and Minister of Health. Although Elliott has an image as a Red Tory, she tacked right during the leadership race and has long been an advocate of a greater role for the private sector in healthcare. Ford rejected appeals from First Nations leaders to retain a stand-alone Minister of Indigenous Affairs (a recommendation of the Ipperwash Inquiry). And in spite of Ford’s promise to diversify the PCs, Ford’s Cabinet choices were overwhelmingly white and male (just seven women and one racialized person) and drew heavily from rural Ontario.

In his first days in office, Ford has begun to quickly act on his agenda. One of Ford’s top priorities is lowering the gas tax, which would deprive the government of about $1-billion a year for transit and infrastructure. Ford also announced a public sector hiring freeze that will certainly cripple the ability of government to provide quality public services. The government has also made the decision to remove OHIP+ from young people whose parents have private coverage, a setback in terms of the movement toward pharmacare. Ford has also moved to strengthen police powers, reversing new police oversight laws recently introduced by the previous Liberal government. And in a move pandering to their right-wing base and nativist sentiment, the Ford government has expressed its intention to withdraw from a federal-provincial agreement to help resettle asylum-seekers.

As Andrew Jackson has recently noted, “a major part of Ford’s base, like that of Trump, is made of disaffected and insecure working class voters who welcomed his message that he would stand up for them against the insiders and the liberal elites. He appealed to these voters with classic ‘pocket book’ promises to cut taxes and to lower the cost of living… These promises seem to have resonated more strongly than the expansion of public services promoted by the Liberals and the NDP, even though Ford’s promised tax cuts would primarily benefit the upper middle-class.” Certainly, Ford will have to implement drastic cuts to public services that working class Ontarians depend on to finance tax cuts. While Ford’s allure will likely wear off among ‘soft’ voters as he governs as a more ‘orthodox’ conservative than he campaigned on, progressives will have to make a renewed case for the importance of public services and collective provision over dependence on the market, and the taxes needed to finance them.

The NDP can be expected to speak out against many Conservative government policies. And several candidates with solid activist backgrounds, such as Joel Harden (Ottawa Centre), Jessica Bell (University-Rosedale), Jill Andrew (Toronto-St. Paul’s), Bhutila Karpoche (Parkdale-High Park) and Rima Berns-McGown (Beaches-East York), were elected, and these MPPs can articulate the demands of social movements in the legislature. Riding associations could be transformed into community action hubs rather than simply be electoral machines. However, the pressure to conform to the norms of parliamentarism will be immense as the NDP will seek to present itself to reassure more centrist voters and present itself as a responsible ‘government in waiting.’ With a large Conservative majority, however, the NDP will have little ability to reverse the overall course, and its parliamentarist focus, if its past actions are at all a guide to the present, will do little to support broad activist organizing across the province.

A broad-based resistance movement outside of the legislature to the hard-right Ford government is essential. A revitalized labour movement is key, as the ‘social unionism’ that led to the “Days of Action” in the Harris years has given way to an extremely divided and conciliatory, ‘business unionist’ approach across all unions (no matter what their rhetoric is). The $15 and Fairness campaign organized a rally in Toronto in defence of recent labour law changes (and attended by much of the NDP caucus). The Workers Action Centre has announced its attention to pressure 16 PC MPPs in ridings where a $15 minimum wage likely has broad support. As the Ford government will certainly prove disastrous for cities (and ‘efficiencies’ will certainly be found by downloading cuts to cities), municipal elections in Toronto and across the province this fall also represent opportunities to elect left and progressive candidates and begin to form a network of ‘rebel cities’ in opposition to the Ford regime. Perhaps, if stronger community-based infrastructure can take hold and revitalized social coalitions form, the labour movement in Ontario might yet again return to leading social struggles and the political space for a radical opening suddenly appear. •