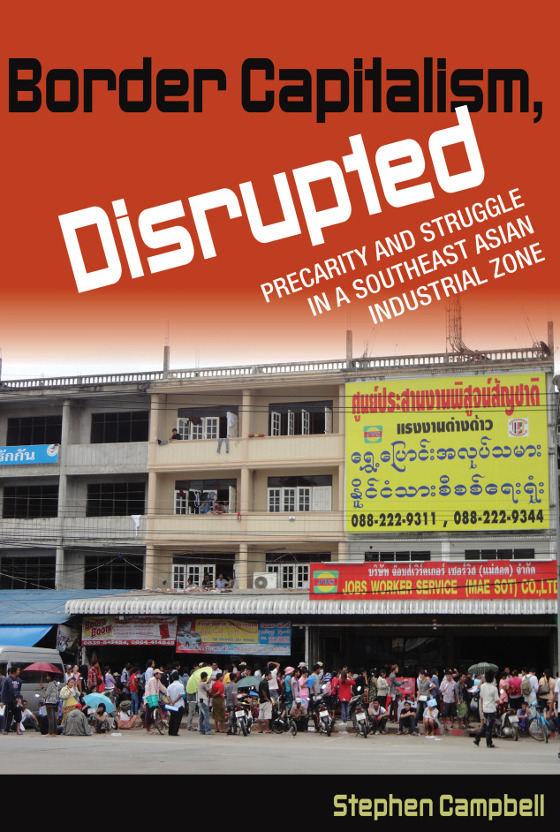

Border Capitalism, Disrupted

Precarity and Struggle in a Southeast Asian Industrial Zone

Through to the back of the cremation grounds where the fields of sugarcane begin, Ko Soe and I coast our bicycles to a stop. It is mid-December, and the sugarcane stocks are tall now, taller than us. Somewhere amid these fields Myanmar migrant workers from the nearby Apex garment factory are hiding. We know this because Ko Soe had only minutes ago been talking with one of them by phone, but then the connection had died; presumably this worker’s phone had run out of power. So now we dismount and look around for an entrance into the fields. The sugarcane is far too dense to walk through, even if we were to leave our bicycles behind. Uncertain how to proceed, we soon spot a man standing, looking at us from the edge of the fields where some car tracks come to an end. Ko Soe calls out and, as we approach, explains to the man that he, too, had worked at Apex, having quit only a few months prior. “We’ve come to see the workers’ situation,” he adds.

The man, whom we now see to be in his early twenties, leads us down a narrow path walled by stocks of sugarcane. When the trail reaches a small stream, we lift our bicycles and carry them along the watercourse until, as directed by our guide, we lay them aside and jump across the brook to an isolated patch of banana trees. It is here that we begin seeing the migrants, bunched together with their baskets of food and clothing, standing, idling, chatting with each other, and reclining on woven mats laid out on the ground. Some of the men are smoking. Others chew quids of betel. A few young children are milling about, and I even spot a couple of babies being held. To my left a young women lies on her back reading a Burmese romance novel. An older woman, speaking by phone to a migrant friend elsewhere, laughs as she explains her predicament. Someone else brings out a tin of biscuits and passes it around to share. The migrants waiting here smile and greet us, thanking us for coming.

The man, whom we now see to be in his early twenties, leads us down a narrow path walled by stocks of sugarcane. When the trail reaches a small stream, we lift our bicycles and carry them along the watercourse until, as directed by our guide, we lay them aside and jump across the brook to an isolated patch of banana trees. It is here that we begin seeing the migrants, bunched together with their baskets of food and clothing, standing, idling, chatting with each other, and reclining on woven mats laid out on the ground. Some of the men are smoking. Others chew quids of betel. A few young children are milling about, and I even spot a couple of babies being held. To my left a young women lies on her back reading a Burmese romance novel. An older woman, speaking by phone to a migrant friend elsewhere, laughs as she explains her predicament. Someone else brings out a tin of biscuits and passes it around to share. The migrants waiting here smile and greet us, thanking us for coming.

Hiding in the Fields

There are, perhaps, about fifty migrants here – mostly women – crowding out small patches of open ground among the banana trees. Although Apex had, I was told, employed upwards of three hundred workers only a few years earlier, the workforce seriously declined when large groups quit in a series of disputes over unpaid wages; others left following the recent closure of the factory’s weaving department. Hence, the migrants hiding here are all that are left, among whom are a handful I know from my previous visits to the factory.

In response to our enquiries about their situation, the migrants tell us that they fled into the sugarcane field this morning while it was still dark, taking with them supplies of rice, boiled eggs, pickled tea, and packaged snacks they had prepared the night before. Initially, they say, the Apex factory owner, who is based in Bangkok, had given instructions that the workers were not to stop production despite news of impending raids. At the last minute, however, the personnel manager got cold feet and told the workers they should temporarily hide out in the nearby sugarcane fields because neither he nor the owner could guarantee their security. The migrants we are speaking with ask us, in turn, what we know of the raids elsewhere, and they name a factory nearby where they have heard the police who came up yesterday from Bangkok have already arrested the workers.

Today is December 15, 2012, one day after the deadline for undocumented migrants in Thailand to register for temporary passports and work permits, thereby escaping their status of illegality. Like the vast majority of the more than 200,000 Myanmar migrants in Mae Sot, in northwest Thailand’s Tak Province, those hiding here amid the sugarcane lack documentation for legal residence and work in Thailand. And like most everyone else in Mae Sot’s migrant community, they knew the registration deadline was approaching; billboards had been put up, and loudspeaker-toting pickup trucks had toured the town, announcing in both Burmese and Thai that those not registered by December 14 would face up to five years in prison, with fines up to 50,000 baht (just over $1,600 U.S.). Government officials in Bangkok had further announced that over one million undocumented migrants would be deported. At other factories in Mae Sot, workers had fled across the nearby border to Buddhist monasteries in the Myanmar town of Myawaddy to wait until the Bangkok police departed. Everyone seemed to know it would only last a few days; this was not the first registration deadline to pass, nor was it the first time raids had been conducted in Mae Sot.

Although most Mae Sot migrants knew in advance of the registration deadline, only a small minority had actually applied for passports and work permits. For the majority, the cost of obtaining these documents through any of the area’s many private passport companies was prohibitive – more than they could save in a year. While it was possible for employers to advance the money to cover the cost, this was not a common practice in Mae Sot. Most factories, such as Apex, simply avoided immigration hassles and potential raids by paying off the local police with monthly fees deducted from the wages of the undocumented migrants they employed. This was, presumably, why the Bangkok (and not Mae Sot) police had been entrusted with the task of enforcing the current registration deadline. In the end, however, very few raids actually occurred in Mae Sot when the registration deadline passed. Out of some four to five hundred factories in the area, I heard mention of only two where such raids apparently took place. And shortly thereafter, the Thai Ministry of Labour announced a three-month extension to the registration period.

Had the threats of raids, arrests, and deportations all been for show? Or had the Thai government heeded humanitarian appeals for an extension to the registration period, such as that voiced by the head of the International Labour Organization? Perhaps policymakers in Bangkok had recognized that mass deportations would have severely undermined Thai industry. In any case, the migrants I met in the sugarcane field went back to work a few days later. They did not, to my knowledge, ever register for passports or work permits while employed at the Apex garment factory, despite the extension granted.

The Social Production of Border Capitalism

The central contention of this book is that the Mae Sot industrial zone, as a spatialized regulatory arrangement, has shaped and made possibly certain forms of class struggle – the effects of which have disrupted and transformed the site’s border capitalism. This argument contrasts with analyses that would see the regulatory arrangement of such zones as being fixed in advance by state policies – developmentalist, neoliberal, or otherwise. I therefore analyze Mae Sot as a dynamic social space – a politically charged space – whose movement is born of the site’s internal contradictions. This is, moreover, a movement that persistently threatens to disrupt the site’s existing social relations, whose conditions of possibility were, in part, born of antecedent class struggles.

The on-the-ground regulation of migrant labour in Mae Sot can thus not be read off of official state policies. Rather, the everyday regulation of migrants in Mae Sot remains contested at the local level, persistently reshaped, and often ambiguously understood by the migrants to whom it applies. As a designated Special Border Economic Zone, Mae Sot’s spatially bounded regulatory arrangement, proximity to the Myanmar border, and distance from central Thailand have enabled a particularly acute situation of despotism organized around the optimization of low-wage, flexible labour for the purposes of capital accumulation and border industrialization. Yet the ways in which migrants have responded to the forms of regulation they confront have forced regulatory actors – such as employers and local government officials – to adjust their regulatory practices accordingly. It is in this way that border capitalism, as both situated relations of production and a spatialized regulatory arrangement, is socially produced.

The argument I advance here is clearly inspired by the work of Henri Lefebvre. But I draw more specifically from the operaista (workerist, often glossed as autonomist Marxist) tradition that grew out of Italian factory workers’ struggles in the 1960s. Writing in an early issue of the workerist journal Classe Operaia, Mario Tronti laid out a critical approach to understanding capitalist development – whether it be technological change, capital relocation, regulatory reform, or the reorganization of the labour process. The particularities of capitalist development, argued Tronti, were best understood not as neutral technical innovations but as reactions to the threats to capital accumulation and managerial prerogative being posed by concrete working-class struggles. As Tronti maintained,

“We too have worked with a concept that puts capitalist development first, and workers second. This is a mistake. And now we have to turn the problem on its head, reverse the polarity, and start again from the beginning: and the beginning is the class struggle of the working class. At the level of socially developed capital, capitalist development becomes subordinated to working-class struggles; it follows behind them, and they set the pace to which the political mechanisms of capital’s own reproduction must be tuned.”

Building on Tronti’s innovations about the primacy of workers’ struggles in catalyzing capitalist development, Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri have extended the argument to account for multiple cycles of restructuring: “Workers’ struggles force capital to restructure; capitalist restructuring destroys the old conditions for worker organization and poses new ones; new worker revolts force capital to restructure again; and so forth.” It is along such workerist lines that I analyze in this book the transformations that have occurred in Mae Sot’s regulatory and industrial landscape.

Taking stock, however, of workerism’s achievements and shortcomings, Steve Wright has pointed out that workerist analysis (at least in its earliest years) was limited by an often narrow focus on collective struggles at the point of production, thereby neglecting “the world beyond the factory wall.” How, we therefore need to ask, are the struggles of subordinate classes outside the workplace related to the reproduction and transformation of capitalist relations at the point of production? And further, how do such struggles affect the broader regulation of proletarian populations? To address these questions I bring into the analysis of capitalist restructuring, along with factory strikes and workforce socialization, struggles over migrants’ mobility outside the workplace, and migrants’ everyday evasion of – and engagement with – the police. The book’s overarching narrative presents these various struggles as constitutive moments in the transformation of Mae Sot’s regulatory geography, at the scale of the workplace and at the scale of the industrial zone.

It needs to be stressed at this point that labour struggles on the border have never been wholly spontaneous outbursts – automatically generated, as it were, by Mae Sot’s regulatory arrangement. Rather, they have emerged out of gradual processes of migrant subjectification and class formation – what I refer to in chapter 5 as everyday recomposition – that are grounded in the relations and experiences of migrants along the border. Particular workplace struggles in Mae Sot have also typically entailed extensive deliberation and planning “behind the scenes” among the workers involved, as in the case I examine in chapter 6. For these reasons, within the circuit of regulation → struggle → new regulation, there are countless agentive moments in which individuals have intervened and influenced the process of Mae Sot’s regulatory transformation. •

This was excerpted from the book Border Capitalism, Disrupted, Cornell University Press (2018), with the author’s permission.