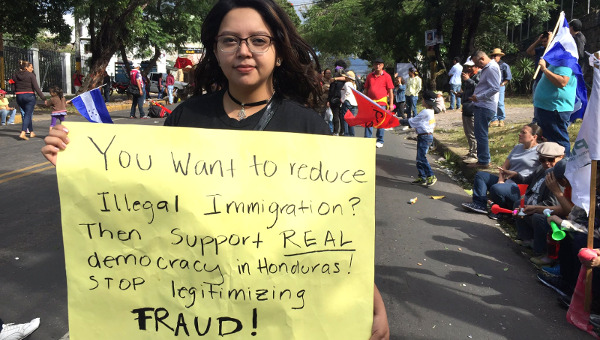

The dictatorship that rules Honduras is in the process of stealing another election, and the Canadian government is doing precisely what it has done the last two times the Honduran dictatorship stole an election: nothing.

Actually, to say Canada is doing nothing is far too generous. In fact, Canada has been arguably the biggest supporter of the de facto government of Honduras, which took over the country in a coup d’etat in 2009, and which has plunged the country into a political, economic, and humanitarian crisis in the eight years since.

As I documented in detail in my recent book, Ottawa and Empire, Canada was instrumental in undermining efforts to restore the legitimate government of Honduras after the military kidnapped the President and seized control of the state in June 2009. While most of the world responded with revulsion to the spectre of military dictatorship in the small Central American country, Canada issued statement after statement suggesting that this was not a coup but a “political crisis” and that the President himself was partly to blame.

Flash forward eight years, and the international media is filled with reports of electoral fraud and political violence in Honduras. Bolivian President Evo Morales denounced the “flagrant fraud in the presidential elections of the Central American country,” the EU and OAS have both demanded a recount and, even before the elections began, The Economist released an audio recording of Honduran officials planning to steal the election as ‘Plan B’ if they didn’t win.

But Canada’s Minister of State Chrystia Freeland has so far issued one tepid statement calling on “all parties to resolve any disagreement peacefully.” It’s an old Canadian obfuscation.

Canada and the Coup

In 2009, then Minister of State Peter Kent consistently repeated the mantra that “all parties” needed to show restraint and negotiate a peaceful solution to the crisis in Honduras. If one knew nothing about Honduras, the statements sounded like classic Canadiana; just another example of Canada asking people to be nice to each other and trying to build peace.

But the reality in Honduras was that the democratic system and the rule of law had been overturned by a military force doing the bidding of the Honduran oligarchy. This new dictatorship was literally killing people in the streets for demanding the restitution of democracy, and the eight years of repression that followed have been some of Honduras’ darkest. So, when Canada called on “all parties” to show restraint, it was in fact creating a deeply misleading impression of what was happening in Honduras. Over many years of research and interviews in Honduras, I met almost no one who agreed with Canada’s interpretation of events.

But in November of that year, this new dictatorship held elections to try to build its legitimacy.

Most of the international community rejected this farce out of hand. The United Nations, the Carter Centre, most international organizations refused to even send representatives to the country for the elections. As they rightly noted, opponents of the regime were being arrested, tortured, and killed. Hundreds of candidates from other parties had dropped off the ballot knowing the election would be stolen. And the Honduran people vowed to boycott the process entirely.

And yet, when the predictably fraudulent results came in, Canada was quick to “congratulate the Honduran people” on holding “relatively free and fair” elections.

The Eight Year Nightmare

Over the next eight years, the regime consolidated its position in Honduras using violence. Activist networks had their leaders targeted for assassination and disappearance; critical media outlets had equipment attacked, signals disrupted, and journalists threatened; impunity for police and military violence opened up space for unchecked activity for criminal gangs.

All of this helped the dictatorship to maintain its hold on power, and it used that power to reward itself and its allies. Austerity measures were imposed on working people, new laws were passed to give local and foreign capital even greater ability to exploit Honduran land and resources, and public funds were looted for the private wealth of the oligarchy.

How did it pull this off? With a little help from its friends, of course.

No country – save perhaps the United States – did more to facilitate the rise of the Honduran dictatorship than Canada. Canada was the first country to send its leader to meet with the regime. Canada signed a free-trade agreement with it, sent a representative to sit on a sham “Truth Commission” about the coup, and Canada argued for Honduras’ re-integration into the Organization of American States and other international organizations.

Canada heaped praise on the regime for resolving the political crisis, which was remarkable, given that the way it resolved the crisis was by killing and intimidating anyone who opposed its dominance of the country. Canadian investment in the country exploded, as companies like Gildan and Goldcorp seized the opportunity to extract profits from a country in crisis. Canada even helped to train Honduran police and military in the tactics of repression they would use against their own people.

Somewhere along the way, the dictatorship stole another election (2013), allowed Honduras to become the murder capital of the world, passed a law allowing private companies to run city-states within Honduran territory, became even more deeply entangled with large criminal networks, and saw tens of thousands of people plunged into abject poverty.

It did all of this with a wink and a nod from Canada, which is now one of the largest sources of foreign investment in Honduras.

The Rise of JOH

Throughout this period, the Honduran social movement has remained steadfast and determined in its opposition to the dictatorship.

In addition to national demonstrations against the government directly, Hondurans have fought to protect their pensions, Indigenous people have fought to protect their territories from mining companies, women have fought against sexual violence and workplace exploitation, communities have opposed privatization of public services, farmers have battled agribusiness over access to land, Garifuna people have organized to resist theft of their territory for cruise ports.

All the while, the regime has consolidated its hold on power and cracked down on this dissent. In 2012, right wing Head of Congress Juan Orlando Hernández (nicknamed JOH, pronounced “ho” in Spanish), who had supported the 2009 coup, carried out a “technical coup” in which four supreme court judges were sacked overnight and replaced by judges loyal to him. The next year, JOH became the President in another round of fraudulent elections. It was a tough blow for the social movement which had put much of its energy into trying to win the elections with its new political party, LIBRE.

That same year, JOH created a new military-police unit, and made sure it was given preferential access to resources, vis-à-vis the armed forces and the national police. It was a play to create a special force loyal to him personally, which he would need if he were to try to extend his stay in office. After all, the military had been convinced to overthrow President Zelaya in 2009 on the (false) claim that he was planning to change the constitution to stay in power for another term.

Sure enough, as JOH stacked the various branches of civilian and military authority with his supporters, he made his play in 2015, amending the constitution to allow himself to run for re-election. The irony was palpable, but Canada issued no statements about this.

This was remarkable, given how much ink Canada had spilled trying to convince the world that the 2009 coup was necessary because Manuel Zelaya planned to run for re-election. This demonstrably false claim was made by Canadian government officials on many occasions, and was repeated by Canada’s representative on the Honduran Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Interesting, indeed, that Canada was so concerned by the prospect of Honduran Presidents running for re-election in 2009 but totally disinterested in the same issue in 2015. It is especially noteworthy because, unlike Manuel Zelaya, the government of Juan Orlando Hernández had been rocked by massive national protests on several occasions, including a wave of protests called the “Torch Marches” in 2015 after it was revealed that he had stolen money from Honduran workers’ pension funds to finance his election campaign.

Power Play

The dictatorship clearly has friends in high places, but it may nevertheless be pushing its luck.

The 2016 murder of Honduras’ most popular activist, the internationally-recognized Berta Cáceres, drew the largest amount of global media attention to Honduran politics since the 2009 coup. While the regime initially worked hard to try to portray the attack as random gang violence, it

was immediately clear that Cáceres was assassinated for her political work, most notably leading the community resistance to the Agua Zarca hydroelectic dam project.

As the 2017 elections neared and JOH indicated that he would, indeed, be running for re-election, he found himself facing a groundswell of opposition not just from the political left but also from disaffected sections of the right.

In order to defeat JOH, a complicated alliance was forged between the party of the movement, LIBRE, and a right-wing anti-corruption party led by TV personality Salvador Nasralla. This decision was not taken without detractors in the movement, who openly and astutely questioned the logic of the alliance, but it did make JOH’s chances of winning a legitimate election slim.

But, just as they had in 2009 and 2013, opponents of this electoral strategy insisted that the regime would not suddenly play by the rules after eight years of breaking them. So far, it appears that they were right again.

The Present Crisis

Despite overwhelming evidence that Nasralla won the election, JOH has declared victory and the Electoral Tribunal has refused to release final vote counts. As the electoral fraud played out, Hondurans yet again took to the streets in protest, and the dictatorship again used violence to quell the demonstrations. Over a week later, fourteen people have been killed, many more injured, but the protests have not ceased.

After a 19-year-old girl was killed last week, Canada’s Chrystia Freeland

finally issued a statement but, as noted above, it contained more obfuscation of facts than condemnation of the regime:

“Noting ongoing delays in the publication of final, definitive election results, Canada insists on the need for election authorities to complete the vote count without interference. Canada also calls for calm and urges all parties to resolve any disagreement peacefully, transparently and in line with the highest democratic and human rights standards.”

Nothing in this statement held the regime accountable for the violence it had unleashed or the fraudulent claim that it had won the election. Instead, Freeland misleadingly characterized the crisis as being caused by “all parties” interfering in the vote counting process. Freeland cannot claim ignorance to the reality of what is happening in Honduras, as she has already received several open letters from Canadian and Honduran organizations demanding that Canada take a strong stand on this matter.

What Now?

Even despite Canada’s support, JOH’s hold on power may be weaker than it appears. As Honduran police and military were called upon to carry out the regime’s repressive will, cracks in the apparatus began to appear. Last week, sections of the Honduran national police refused to carry out the crack down against protestors.

While some optimistically believed this to be a sign that the police were with the people, such a naïve assumption must be set aside. In a report I produced for a Norwegian NGO in 2016, I noted that the police are deeply corrupted by organized crime and fully committed to broadly carrying out the will of the oligarchy. They are, however, frustrated by the lack of resources they are receiving from the JOH government.

Resentment between the factions in the ruling apparatus have emerged as JOH has made his push for a personal dictatorship. He anticipated this as early as 2012 when he worked towards the creation of the military-police unit. Over the past four years, he has showered that organization with resources and counts upon its loyalty. While he has so far maintained the allegiance of the traditional Honduran military, he is aware of it’s discomfort with his tampering with the constitution and running for re-election.

Fractions between the repressive forces in Honduras are mirrored by divisions within the oligarchy itself. As organized criminal gangs have infiltrated the state, it has become impossible to separate ‘clean’ politicians from ‘dirty’ ones. While many in the oligarchy are perfectly comfortable with this, there are those who feel that it undermines Honduras’ ability to be a functional capitalist state attracting foreign investment.

Salvador Nasralla, who undoubtedly garnered the most votes in this election, is in many ways reflective of that latter position. Known to be of the political right, his presence in opposition to JOH does make a wider rebellion within the police or military more likely.

This remains, however, an improbable outcome.

The New Canadian Imperialism

The sad reality in Honduras is that despite naked fraud and violence, the dictatorship now centred on Juan Orlando Hernández will, in all likelihood, wait out the current cycle of protest and opposition. When international attention has died down, as it has already begun to do, JOH will consolidate his position, swiftly and mercilessly punish those who opposed him, and continue running Honduras as his personal fiefdom; a narco-state over which he presides with violence and fear, to the benefit of a handful of wealthy families in Honduras and foreign businesses.

Many of those foreign businesses are based in Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver. Canada’s support for the Honduran dictatorship over these eight years has been part of a broader dynamic in Canadian foreign policy; a turn to what many have called a new imperialism.

This Canadian imperialism uses Canada’s diplomatic, political, and military power to create a world of profitable opportunities for Canadian capital, whether in Honduras, Haiti, Afghanistan, or elsewhere. It cuts across party lines, having been a guiding principle for not just the Conservative government but also the Liberal administrations that came before and after.

Canadians who believe that their country is a good citizen of the world would do well to take a closer look at the nightmare in Honduras. After all, it is a nightmare Canada has helped create.

For more information and solidarity efforts, consult the Honduras Solidarity Network or the Latin American and Caribbean Solidarity Network. •