More than 12,000 Ontario public college faculty were on the picket line rather than in their classrooms on Monday morning after talks between the Ontario Public Service Employees Union (OPSEU) and the College Employer Council failed to produce a tentative collective agreement.

“On October 14, we presented Council with a streamlined offer that represented what faculty consider to be the bare minimum we need to ensure quality education for students and treat contract faculty fairly,” said JP Hornick, chair of the union bargaining team. “We carefully crafted a proposal that responded to Council’s concerns about costs in a fair and reasonable way.”

“Unfortunately, Council refused to agree on even the no-cost items, such as longer contracts for contract faculty and academic freedom,” she said. “This leaves us with no choice but to withdraw our services until such time as our employer is ready to negotiate seriously.”

Hornick said Council is committed to a “Walmart model of education” based on reducing the role of full-time faculty and exploiting underpaid contract workers who have no job security beyond one semester.

OPSEU President Warren (Smokey) Thomas called the current impasse “regrettable” but said college faculty have the full backing of the union’s 130,000 members and their $72-million strike fund.

“Our union has a track record of getting deals done without work stoppages,” he said. “Unfortunately, that has not happened in this case. Nonetheless, I encourage the colleges to get back to the table so we can wrap this up swiftly, for the good of students and faculty alike.”

OPSEU represents professors, instructors, counsellors, and librarians working at 24 public colleges across Ontario. To view the union’s most recent offer, please visit www.collegefaculty.org.

Either Invest or Face More Turmoil at Ontario’s Colleges and Universities

John Peters

Ontario college faculty at Seneca, Humber, Centennial, and George Brown College are now on strike in Toronto, as well as across the province, affecting 24 colleges and more than 200,000 full-time students, and hundreds of thousands more enrolled on a part-time basis. This follows a strike at Laurentian University in Sudbury in early October. These are but the latest stories in the never-ending upheaval across Canada’s and Ontario’s post-secondary education sector.

Since 2008, there have been 20 faculty association strikes and countless others led by unions representing other members of the university and college community, including those recently at York University (2009, 2015) and the University of Toronto (2015). In Ontario’s college sector, this is the second province wide strike of faculty since the 1980s, but there have been many other smaller labour conflicts at Ontario’s colleges.

For many Canadians, all this may seem a little strange. Professors are better known for chasing neutrinos down mine shafts, or for holding events celebrating Margaret Atwood, than for walking picket lines. Yet one doesn’t have to look too far for reasons why faculty and graduate students are striking – it is of course about money. But not in the usual sense that we think about money during strikes.

Rather, the first big financial issue is that Canadian governments have cut public funding of universities and colleges. In public speeches, government officials talk in lofty terms of their investment in public post-secondary education. But the reality is rather different. Canada has actually cut its public funding since 2008, and now we rank in the bottom half of advanced economies, spending well below what Denmark, Norway, and Sweden invest in their public post-secondary teaching, research, and innovation.

The picture is the same in Ontario, where the provincial government has reduced public funding for universities and colleges and now ranks last in public per-student funding in Canada.

Walmart-ization of Colleges

The second thorny issue relates to how quickly university and college administrators’ have seized on the “modern and efficient” business models for university operation.

On the basis of ostensibly saving money, “Run the universities and colleges like a corporation” has become the new mantra, often followed by the equally faulty idea that students are the “new customers” and that faculty have to work harder to serve them better.

The outcomes? None that is surprising. Ontario universities and colleges rely more on tuition fee increases and student debt than any others in Canada.

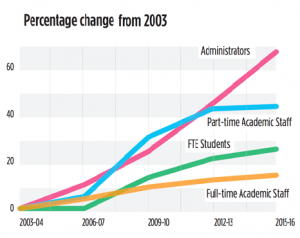

Universities and colleges have also hired more six-figure administrators than ever before, doubling their numbers of administrators and more than doubling their administration costs into the millions over the past decade.

Universities and colleges have also appointed corporate executives to their boards of governors to oversee new arcane financing arrangements, while turning to the private sector for lawyers to dispense advice on how to run negotiations and seek concessions from their faculty.

Ontario universities and colleges rely more on tuition fee increases and student debt than any others in Canada.

Now university and college administrations across Canada (often following government directives) have opted for the next step in their new “education as a business” model – arguing that they need to cut costs and increase workloads. Typically, this has led to program and staff cuts, while also ballooning class sizes and hiring more part-time and temporary faculty.

But for faculty this has meant the agonizing choice to either allow the administration to erode the quality of education, or defend the quality of public education and go on strike. It doesn’t have to be this way.

Reinvesting for the Future

Rather than cutting funding, governments need to make the choice to reinvest in post-secondary education. The federal government’s current transfers to post-secondary education are shameful: less than 0.2 per cent of GDP. Cash-strapped provincial governments’ public investments on post-secondary education are only modestly better.

Publicly invest and eliminate tuition fees, as most West European countries do, and the federal and provincial governments can actually claim to be supporting universities as “drivers of innovation.”

Universities also need to stop thinking about themselves as being private businesses. They are not. The more practical solution is for universities and colleges to operate like public institutions again – letting professors and students have a say in how their institutions are run, and ensure that universities operate on a not-for-profit basis.

Establish public university and college boards to ensure accountability, cut executive salaries, eliminate private endowments and business appointees, and have business actually step up and hire students into apprenticeships and internships, and we can again be on the path to making our universities better places for teaching, discovery, and engagement. •

John Peters is an associate professor of labour studies at the School of Northern and Community Studies, Laurentian University. This article first published by the Toronto Star.

Faculty at Ontario’s Colleges Just Went on Strike. Here’s What They’re Fighting For.

Thousands of faculty at 24 colleges in Ontario are heading to the picket line in a battle over the explosion of precarious work at Ontario’s college campuses.

The 12,000 professors, instructors, counsellors and librarians represented by the Ontario Public Service Employees Union (OPSEU) were forced to strike after management rejected a final offer from the union to end systemic job insecurity at Ontario’s colleges.

In its rejected final pitch to the College Employer Council, OPSEU listed the following asks as bare minimum requirements for striking a deal:

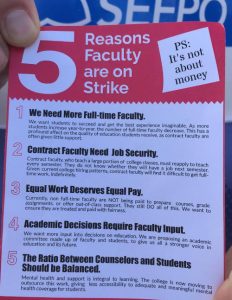

- Colleges agree to end their dependence on temporary contract work by adopting a 50:50 ratio between full-time and contract faculty.

- Colleges agree to increase job security for part-time faculty.

- Colleges grant academic freedom to faculty, giving them a stronger voice in academic decision-making and protect the integrity of their work.

The union’s demands highlight the increasingly insecure working conditions for faculty at Ontario’s colleges and the erosion of quality as the provincial government has reduced funding.

Here are a few reasons why the working conditions facing faculty at Ontario’s colleges is actually a symptom of what’s being called Ontario’s “Walmart model of (postsecondary) education.”

The Rise of Contract Work at Ontario Colleges

According to data from the College Employer Council, part-time contract instructors now make up a staggering 70% of all Ontario college teachers.

In the last decade alone, the number of part-time contract teachers at Ontario colleges have exploded, growing at more than double the pace of full-time academic staff.

Meanwhile, the number of college administrative staff has increased by more than 77% – working out to one administrator for every three full-time faculty members (Ontario high school’s have one administrator per 12 teachers, by comparison), something OPSEU suggests is a symptom of how Ontario’s “college education is being re-shaped according to a corporate model.”

College Teachers are Struggling to Make Ends Meet

Even though they’re doing the same work as full-time faculty, teachers working on contracts are paid well below Canada’s median income earning an average of less than $30,000 per year with no benefits or job security.

What’s more, those teachers are usually assigned classes at the last minute with no no time to prepare or meet with students, plus many college teachers in Ontario are forced to overload their teaching schedules or work multiple jobs just to make rent and pay their bills.

And as one contract instructor points out, under existing working conditions, many college teachers are effectively earning little more than minimum wage:

“Course development (some of which I have done from scratch) and maintenance (keeping up with current research) is time consuming, as is marking of tests and assignments, student contact (whether in person or my email), upkeep of online resources, and administrative functions.

“When I factor these activities in, I am likely making just over the provincial minimum wage.”

Trapped in a Cycle of Job Insecurity at Ontario Colleges

Another problem facing contract faculty is there is no “recognition of seniority.”

OPSEU points out contract instructors are forced to reapply for the same jobs each semester – regardless of how good they are or how long they’ve taught a course, experience and seniority don’t offer contract faculty a clear path to full-time positions.

“Too often in the current context,” OPSEU notes, “these faculty are left trapped in an ongoing cycle of short-term contracts.”

Rising Class Sizes at Ontario Colleges

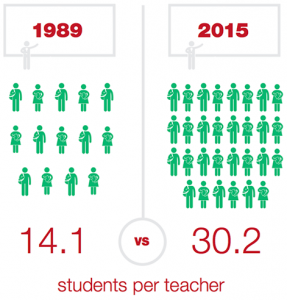

At the same time as colleges have shifted to part-time contract faculty, the number of students enrolled in college courses has exploded.

College enrollments have doubled since 1989, yet there are now “roughly 1,000 fewer full-time faculty to teach 100,000 more students” than there were 28 years ago.

As a result, this is undermining the integrity of Ontario’s college system – Ontario college students are now “paying more for reduced access to securely employed and fairly-compensated faculty who can focus on students’ needs in the short- and long term.” •

This article first published by the Press Progress.

Ontario College Strike 101

Chris Grawey

On Monday, October 16, the 12,000 members of OPSEU’s College Academic Division – professors, instructors, librarians, and counsellors at Ontario’s 24 public colleges – hit the picket line after the College Employer Council rejected OPSEU’s final offer on October 15. OPSEU’s membership gave the bargaining committee a 68% strike mandate in September.

The final offer presented by OPSEU’s bargaining committee was a direct response to the Council’s concerns and it includes three central issues:

- 50:50 ratio of full-time to contract faculty

- Job security for partial-load faculty

- Academic freedom

The three proposals would be beneficial to both faculty and to students, as improved working conditions for instructors – through enhanced job security, more full-time positions, and greater academic freedom – would lead to better learning conditions for students. Faculty are also loudly calling for lower paid contract faculty to have Equal Pay for Equal Work and that this provision be part of the Ontario government’s Bill 148, the legislation containing the $15 minimum wage and other labour reforms.

The strike will be faculty’s fourth in the Ontario college system’s fifty year history, with each previous strike lasting four weeks or less. An academic year has never been lost due to a strike.

With that being said, in the event of a prolonged strike, colleges should financially compensate students for lost class time, as many students are struggling and should not be forced to pay for cancelled classes. The colleges should not be profiting from the labour dispute.

How We Got Here

The labour dispute can best be understood by starting with the broad political and economic trends over the past 40 years. During this period, the economic and political elites in this country have shifted to the right on economic policy and ideology. This shift to the right entailed cutting taxes for corporations and the wealthiest, privatizing public assets, signing free trade deals, underfunding and gutting social programs, and attacking trade unions.

By comparison, from the 1950s until the 1980s, most jobs were premised on the standard employment relationship that consisted of full-time permanent status, good wages and benefits, mostly 9-5 hours of work, and one job for life. Over the past four decades, with the shift to the right on economic policy, many of these jobs have been lost due to technological change and the offshoring of production, while many of the jobs created are precarious ones centred in the service and retail sectors which are premised on low-wages, a lack of benefits and part-time, temporary and/or contract status where hours are unpredictable and people are forced to survive by working multiple jobs.

These policies have resulted in unprecedented levels of wealth and income inequality and record-high corporate profits. Ultimately, the rich have gotten richer at the expense of ordinary people.

Underfunding, Tuition Hikes, Precarious Jobs

Post-secondary institutions have not escaped these trends. For instance, government funding has declined substantially and there is a greater reliance on the private sector. In 1992, 77% of college funding came from the government. By 2013, funding from the government for Ontario’s colleges and universities fell below 50%.

This funding shortfall has resulted in Ontario holding the distinction of having the lowest funding per-student and the highest university tuition fees. According to 2012 data, Ontario colleges are funded at rates 21% below the national average.

From 1993 to 2013, undergraduate tuition fees at universities outpaced inflation by 572% and college tuition fees outpaced inflation by 318%. In addition, from 1993 to 2015, tuition fees tripled for undergraduate students in Ontario. Outrageous fee hikes have left students with average debt loads in the tens of thousands of dollars in a less than desirable labour market.

As students have been getting ripped off, so have our instructors. This is apparent with the explosion of precarious contract jobs. Currently, over 70% of instructors are contract faculty with no job security and benefits. Average pay for a contact faculty member with a full-time teaching load is less than $30,000.

While college enrollment has nearly doubled since 1989, full-time faculty numbers have dropped, resulting in 1,000 fewer full-time faculty to teach more than 100,000 more students.

Contract faculty are also not often paid for preparation time or for grading assignments, which means that many instructors earn around the minimum wage when factoring in these added responsibilities. From semester to semester, contract faculty must apply for work at the college, despite the fact that many have been teaching the same courses for many years. Often, they are not informed until the last minute whether they will be teaching, which means they have minimal time to prepare for the school year.

Because of this, many of our instructors are forced to work two or three jobs to make ends meet. In addition, these trends have led to the departure of many highly talented and educated instructors from the college system to seek employment opportunities elsewhere.

The union’s proposal for a 50:50 ratio of full-time to contract faculty, and job security for partial-load faculty, are a step in the right direction to alleviating the problems contract faculty must confront on a daily basis. If won, these proposals would be a great improvement for many instructors that will improve college education.

A Bloated Administration with Corporate Blinders

While working conditions have declined and students’ tuition fees have skyrocketed, there has been a significant increase in the number of administrative positions. From 2002 to 2015, administrative positions at Ontario colleges increased by more than 77%. Many of these positions are completely unrelated to actual education.

This expanding bureaucracy of college governance replicates a corporate boardroom model that has no place in an education system. Front-line college workers are largely excluded from the decision-making process, including important education decisions. Administrators and the Board of Governors are making important decisions on admissions, instructional methods, and staffing when they possess no knowledge or expertise on the matter.

OPSEU’s proposal on academic freedom would permit faculty to make academic decisions about their courses and research, rather than the out-of-touch Board of Governors whose actions on tuition fees and casualizing college jobs are in direct opposition to the interests of college workers and students. The Board of Governors’ financial decisions are about rubber-stamping the larger political agenda talked about earlier. Their decisions are not about improving the quality of the education offered to students.

Post-secondary institutions have been transformed into top-heavy bureaucracies that reflect this corporate culture. Government underfunding and the corporatization of education governance has led to CEO salaries for school presidents; Boards of Governors and Trustees that consist of elites and powerbrokers; the casualization of the college workforce; ballooning tuition fees; larger class sizes and less access to instructors; dismantling of entire programs; publicly-funded research that subsidizes corporate agendas; treating students as consumers, transforming degrees into commodities bought and sold; and the narrowing of education down to nothing more than a means to a job in a lousy employer-dominated labour market.

Who Should Students Blame?

Many students have expressed their frustrations with the strike, as the disruption to their semester and loss of class time will impact their day to day lives and educational experience. There is no denying this fact.

However, anger directed at faculty members who are exerting their democratic rights is misguided. For many years, faculty have been raising their grievances with the Ontario government and the College Employer Council with no action from either party. During this time of inaction, more full-time positions have been lost and more contract positions have been created.

With no action from the government or from the Council, the instructors’ backs are against the wall and they have no alternative but to take strike action. These decisions are never taken lightly. Nonetheless, this is the only avenue to take to get the Council to seriously negotiate and for the faculty to improve their working conditions. To think otherwise reveals a degree of naivety to how the government and the Council function and operate.

It is clear that the government and the Council’s inaction and unwillingness to listen to the concerns of workers over the years are responsible for the labour dispute. If you were a worker with little to no job security, low compensation for work performed, and struggling to make ends meet, what would you do?

College Workers and Students United

Students recognize the importance of their instructors in helping them obtain a specific skill set and the required training and qualifications to pursue meaningful employment opportunities that consist of good working conditions and livable wages. The question then to be asked is: if students attend post-secondary with the intent of finding meaningful employment after graduation, then why do the vast majority of instructors who help them achieve their goals deserve less than this?

Ultimately, the faculty deserve our support, as the majority of graduates entering the labour market will confront the same employment struggles that our instructors are currently confronting – low-wages, no benefits, part-time/contract status, and high levels of stress – whether we are paralegals, tradespeople, or in the tech field.

Until we come to that realization that workers and students struggles are interconnected, the bosses will continue to divide and conquer and working people will be fighting over crumbs. The capitalists who consistently attack workers in the private sector – by union busting, introducing labour-saving technologies, by shipping jobs overseas, and by opposing and lying about a $15 minimum wage in Ontario – are the same ones who sit on Boards of Governors and Trustees and vote to raise tuition fees. They are the same lot who have been unwilling to seriously negotiate with faculty.

If workers and students want to address precarious work and growing levels of inequality, and abolish tuition fees, we must mobilize and be ready to take on the bosses and the government. History demonstrates that the capitalist class never handed anything to workers and students without sustained pressure from below.

At this point in time, students can support the striking faculty by showing up to the picket line, by forming student/worker alliances, and by writing letters to administrators and the Council to exert pressure on them to get back to the bargaining table and negotiate a fair deal. •

Chris Grawey is a Mohawk College paralegal student. This article first published by Rank and File.