The New (Canadian) Imperialism, in Honduras – An interview with Tyler Shipley

Tanner Mirrlees interviews Tyler Shipley about Ottawa and Empire: Canada and the Military Coup in Honduras (Between the Lines, 2017). They discuss pertinent topics such as: the meaning of Canadian imperialism, the Canadian State’s coercive and persuasive power, the gap between Canadian foreign policy words and deeds, Canada’s foreign policy ideologies, the Canadian news media, pedagogy, and popular culture.

Tanner Mirrlees (TM): Your book is a focused, lucid, and valuable contribution to current research on the 2009 coup d’etat of the democratically elected president of Honduras, Manuel Zelaya. What inspired you to write this book? How did you select Honduras as your book’s focus?

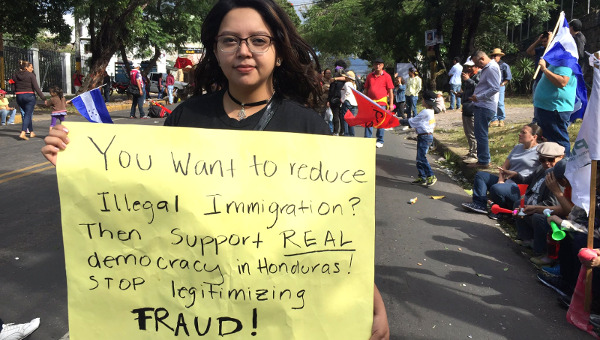

Tyler Shipley (TS): The whole project was, in a way, an accident. I was in Guatemala in 2009 when the coup took place, and it was headline news in Central America for months, so it was impossible to miss the gravity of the situation. My first trips to Honduras that year were not research trips at all but, rather, were to participate in the larger solidarity efforts by progressives across the hemisphere. I went to Honduras to try to help the peaceful resistance movement in whatever way I could. I joined marches and demonstrations and documented the violence of the military government that had taken over. I was dumbfounded that Canada would so deeply implicate itself in supporting a violent dictatorship. I knew at that moment that this was a story that needed to be told in detail.The moment that I knew I needed to write about this in more detail was when I realised that the Canadian government was steadfastly on the wrong side. I remember, in particular, in November 2009 when the military government (which had just abducted and overthrown a President) held “elections.” Most of the international community refused to even play along with the idea that this government which was killing people and attacking its opposition could possibly hold legitimate elections. I was in the country while the process took place and it was very evident to most Hondurans that it was a sham, in fact, an overwhelming majority of the population refused to even participate. And the next day, I remember blinking at the TV, watching the Canadian government congratulate “the Honduran people” on holding “mostly fair and free elections.”

TM: What was your main goal in writing this book?

TS: If there is any one primary purpose of this book it is to shatter the myth that Canada is out there doing good in the world.

TM: Your book, in addition to doing that, is excellently researched and eminently readable. Packed with data, the voices of the Honduran people afflicted by the coup, and personal anecdotes, the book is cogent and accessibly written. When did you start research for this book? How did you go about writing it?

TS: Thanks Tanner! It was very important to me that the book be written clearly and in a way that would engage a wide audience, because academic work is only valuable insofar as it can be mobilized to change the world (for the better, one hopes). In this case, it helped that my research was so rooted in talking with people. Between 2009 and 2015 I travelled to Honduras several times and did interviews with activists in the social movement that represents a wide cross-section of Honduran society. I took seriously my responsibility to accurately reflect the analysis and opinion of ordinary Hondurans in the popular movement, and so a lot of my work was in simply reflecting their words and analyzing the debates that exist within the movement.

I also spent a lot of time going through the historiography on Honduras. While the historical sections of the book are fairly brief, I don’t think it would have been appropriate to put this work out there without a solid sense of Honduran history. It’s so often the case that colonial powers try to deny, erase, or re-write the history of a people they are conquering. In Honduras, that often manifests as Canadian politicians saying “Honduras has a traditional culture of violence” which suggests that if there is violence in Honduras it is because Hondurans are just naturally violent. Looking at Honduran history, one sees that violence has been brought to that country by colonial powers for centuries, and this pattern is repeating itself again today.

Finally, I immersed myself in the discussions that have taken place in Canada about this country’s role in imperialism. Ultimately, the book is about Canada’s role in the world, and I am staking a position within those debates. In my view, the Honduran coup fits a pattern that has emerged wherein Canada is behaving as an imperial power in the world, distinct from the U.S. but in cooperation with it, and so I spent a lot of time with the scholarship on Canadian foreign policy and especially on the question of Canadian imperialism.

TS: The primary agents of the coup in Honduras were the oligarchy (a group of super rich families that dominate Honduran economic and political life) and the military, which has seen its influence diminish since the late 1990s and saw the coup as an opportunity to re-assert its importance to the oligarchy. These forces wanted to stop the program of social reform undertaken by the Zelaya government (2006-2009) which was responding to an organized popular movement demanding change. The coup was supported primarily by the U.S. and Canada, which have significant geopolitical and business interests in Honduras that were threatened by the social movement (and, by extension, the Zelaya government).

TM: What were the main reasons for the Canadian State and corporate class’s implicit support for the coup? More broadly, what are Canada’s “interests” in Honduras?

TS: Canada seeks, in Honduras, a compliant partner in neoliberalism. The Canadian government, reflecting the needs of Canadian capital, wants a government in Honduras that will support the interests of Canadian businesses operating there. Zelaya was fine until he started to interfere with Canadian profits. The most important sectors here are mining, garment manufacturing, and tourism. In the former case, for instance, the Zelaya government upheld a moratorium on granting new mining concessions while it tried to write a new mining code that would better protect labour and the environment. Canada prefers a government like the one that took over after the coup, which cracked down on popular protest, lifted the moratorium, and invited Canadian mining companies to help write the new mining code. Not surprisingly, that new mining code didn’t protect labour or the environment, making it easier for Canadian companies to steal land, build mines that poison the water supply, and take all those profits back to Bay Street without paying taxes to support the Honduran state infrastructure.

TM: The social consequences of Canada’s diplomatic and corporate presence in Honduras are…

TS: Disastrous! Canada’s support for the military coup has made things worse for so many Hondurans. Remember, prior to the coup, Hondurans were mobilizing to fight back against the oligarchs and neoliberalism. Millions of people have been fighting against these things, for decades. But the coup provided an opportunity for the state to crack down hard against those mobilizations. The list of people detained, harassed, assaulted, tortured, kidnapped, even killed, is long and growing. This violence unleashed in 2009 and continuing in 2017 is taking place with direct Canadian complicity.

TM: Your book makes an important contribution to emerging theorizations of and grounded research on Canada as an imperial power. In “Chapter 5 – Middle Power or Empire’s Ally,” you extrapolate from the focused and contemporary case study of Canada’s support for the military coup in Honduras to discuss Canada’s broader and older imperial dynamics. Can you elaborate upon what you mean by “Canadian imperialism”? What are the key characteristics of the Canadian imperial project in Honduras?

TS: There is a pervasive belief, even among critical-minded Canadians, that when Canada gets caught up in bad things in the world, it is a product of our dependence on the United States. Linda McQuaig described this as “holding the bully’s coat.” The assumption is that Canada would do good in the world, but we need to placate the U.S., and so we find ourselves making terrible decisions because we don’t want to upset Clinton, Bush, Obama, or Trump.

I don’t accept this. Following the careful analysis of Jerome Klassen and others, I argue that Canada pursues imperialist project because it is in the interests of the Canadian capitalist class. Full stop. Of course, this often means cooperating with the United States, because it, too, is pursuing an imperialist project. But, as I detail in the book, Canada has a very powerful and concentrated class of super rich, who exert tremendous influence over the state. They expect the Canadian government to protect their ability to make profits abroad, and they almost always get their wish. In fact, the Canadian government articulated in 2013 that its primary concern when making foreign policy decisions was the interests of Canadian businesses abroad. It’s not a conspiracy, they are quite open about it.

This is very clear in Honduras, where mining capital (but also sweatshop employers like Gildan or tourist mega-developers like Randy Jorgensen) has benefitted tremendously from the successful prosecution of the military coup. Had Canada thrown its diplomatic weight into criticizing the military coup and demanding the restoration of democracy, which we might have expected it to do, this would have been bad for business. So, instead, Canada sided with the dictatorship, overlooked the body count, ignored the abuses of human rights and the shutdown of the critical press in Honduras, and helped the oligarchy carry out the coup successfully. This fits my definition of imperialism; it uses Canada’s power to interfere in the democratic sovereignty of another state, for the

benefit of the wealthy classes in Canada, and to the detriment of most people in Honduras.

TM: That is a helpful definition of Canadian imperialism, so let’s move on to discuss the instruments of imperialism. The political and economic actors driving imperial projects harness tools of coercion and persuasion to achieve their interests. Did the Canadian imperial project in Honduras entail the Canadian State and corporate class using violence and consent-building to compel and cajole the subordination of Hondurans? Do any concrete examples come to mind? Or is this too simple a read of Canadian imperialism?

TS: Well, one of the interesting aspects of the Honduran case – at least in terms of Canadian imperialism – is that there hasn’t been any significant need for direct violence by the Canadian state. In other cases, like Afghanistan or even Haiti, Canadian interests have been facilitated by direct intervention. But here, Canada relied primarily on the Honduran oligarchy and military to do all of the “dirty work” necessary to support Canada’s interests.

Essentially, Honduras was engaged in a major episode of class struggle, with the ruling oligarchy trying to re-assert its dominance over an increasingly defiant and organized movement of Hondurans from subordinated classes. The movement was made up of primarily working people and peasants, who asserted themselves not just along traditional class-based organizations (ie. trade unions or campesino networks) but also through Indigenous, Garifuna, environmental, feminist, queer, student, and other specific and/or regional networks. This social movement was slowly gaining the upper hand, and the coup was an attempt by the oligarchy to immediately regain control, as their normal representative (the President) had increasingly succumbed to the pressures placed by the social movement. The coup wasn’t really a blow to the state, then, as much as it was a blow to the social movement and the popular classes of Honduras.

Canada’s interests were served by quietly supporting the ruling class in this round of class struggle. Canada worked hard to frame the crisis as though it were a showdown between rival political factions, President Zelaya on one side, coup-President Micheletti on the other. This erased the central role of the Honduran masses, and made it seem as though it was a squabble between two politicians with the people “caught in the middle.” Canada also repeatedly “called for restraint from all parties” and implicitly blamed President Zelaya for the crisis. This was a cynical manipulation. As I describe it to my students, it was as if I were teaching a class and someone burst into the room and started punching one of the students, and my reaction was to say “everyone needs to settle down here!” Everyone? That doesn’t make sense.

Of course, it did make sense from the standpoint of Canadian capital, which wanted to facilitate the coup and make sure there was not enough international pressure to block its successful completion.

TM: Your book shows there to be a huge “credibility gap” between what Canadian foreign policy and business elites say about Canada’s diplomatic and corporate presence in Honduras and what is really happening on the ground in Honduras. How big is the gap between what elites say “Canada is doing” in Honduras and what representatives of Canada are actually doing there?

TS: Yes, as I noted above, this disconnect is very significant in the Honduran case. The Canadian government claims, on its website and in its public statements, that it helped Honduras resolve its political crisis in 2009. This is utter nonsense. Canada supported those who carried out the coup and helped them consolidate it over the ensuing years. So yes, the gap is enormous.

TM: What are some significant examples of the “word and deed” disconnect?

TS: I’ll highlight three. In 2010, Canadian Minister of State Peter Kent went to Honduras to meet the (coup-)President and congratulate him on his victory in the (sham) elections. His statement enthusiastically endorsed the Honduran government for moving past the crisis. In the weeks leading up to Kent’s visit, three prominent activists in the resistance were assassinated, one of them hanged, in direct retribution for their political opposition. Peter Kent’s office knew about this, because open letters were sent to him detailing what was happening. With a straight face, he praised the government for respecting human rights.

In 2011, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper travelled to Honduras to sign the Canada-Honduras Free Trade Agreement. While there, he praised the good work of Canadian corporations, suggesting that they could stand as a model of corporate social responsibility that Honduran companies could follow. He had been inundated with reports and letters in the weeks leading up to his visit from activists in CODEMUH, a women’s organization that works on behalf of employees in the Gildan Activewear sweatshops in Honduras. These sweatshops are brutally exploitative, and CODEMUH has documented hundreds of workplace injuries, while Gildan typically uses injuries as justifications for lower pay or layoffs. Naturally, then, Stephen Harper praised Gildan in particular and toured one of its facilities.

Finally, a Canadian lawyer with experience in the foreign service and working with mining companies was offered by Canada to sit on the Honduran “Truth and Reconciliation Commission,” struck to add a veneer of legitimacy to the new government following the coup. The Commission was widely criticized in Honduras for being utterly disconnected from the social movement that was under attack, but Michael Kergin, the Canadian on the panel, was enthusiastic about his participation and used the opportunity to suggest that Zelaya was the real problem. The

military, he insisted, may have gone too far in kidnapping the President, but the President himself was the real problem and Honduras was better for having moved past it all.

So in each case, Canadian officials obscure the truth and deflect attention away from the class conflict and struggle that was at the centre of the Honduran crisis. In this way, they shield the oligarchy and Canadian capital from being held accountable for their crimes against Honduran people.

TM: I feel a great deal of shame now knowing that Canadian officials did this in the name of Canada. It also makes me think about how imperialism entails much more than capitalist expansion supported by State diplomacy and military violence. In Culture and Imperialism, Edward Said (1993) showed how imperialism involves corporate and governmental practices, but practices supported, legitimized and justified by ideas and beliefs about the national self and the other. In addition to being a stellar political-economic study of Canadian imperialism, your book highlights the importance of culture and ideology to Canadian imperialism. What, in your assessment, are the key culture-ideologies supporting Canada’s presence in Honduras and Canada’s global conduct more broadly at the present time?

TS: I think this cultural stuff is a really crucial piece, and it is odd to me that there isn’t more critical work on Canadian culture. I begin all my courses about Canada with a discussion where I ask students to talk about what they think Canada represents. The answers range from hockey and maple syrup to peacekeeping and generosity, all with a fundamental assumption that Canada has good intentions in the world. This idea of Canadian “goodness” is deeply rooted. Although many people think it is built in comparison to the U.S., I think it goes deeper and, in fact, comes out of Canada’s colonial legacy.

TM: How so?

TS: Canada is founded upon colonialism and genocide, there’s no way around this fact. The national culture is rooted in the Anglo-Canadian vision of itself as a saviour of civilization, come to rescue the Indigenous people from their savagery and settle this “vast empty land.” The discourse of “saving” Indigenous people existed right alongside the open willingness to destroy them. As one Canadian politician put it, “the Indian must disappear before the march of civilization.”

TM:Can you give a few examples of how Canada’s colonial legacy informs the imperial culture-ideologies of the present, and how these pervade foreign policy “common sense”?

A horrifying vision of Canadian cultural superiority is reflected in so much of Canadian foreign policy in the past 150 years.Whether in support for Britain’s Boer War in South Africa, sympathy for Nazi Germany in the 1930s (Prime Minister King said that Hitler would do great things in 1938), or more recent events (like the torture and murder of Somali children during Canada’s “peacekeeping” mission in the 1990s), there is always a kernel of certainty that Canadians represent civilization and order. Afghanistan? We helped them develop democracy and we liberated women. Haiti? We provide relief to the poor and help them build infrastructure. Honduras? We helped them resolve their political crisis. In each case, we tell ourselves that we are the good guys. By extension, we make assumptions about the other. We assume Afghans are backwards, irrational, religious zealots, or that Haitians are bloodthirsty maniacs who can’t run a functional state. By the way, these aren’t exaggerations, they are reflected in actual Canadian statements, especially by soldiers and others who deliver Canadian “help.”

TM: But so much of the everyday culture of Canadian imperialism is reproduced in the hearts and minds of Canadians in far less brazen and obvious ways.

TS: Yes, much of this is packaged up for the average Canadian as hokey, down-home, Canadiana. Gosh, we’re so humble, we always say sorry. Aw shucks, we just like us some hockey and beer, eh? We sell ourselves a myth that we are unassuming and well-intentioned, and then when the Canadian military intervenes somewhere, we assume it does so on the basis of “good Canadian values.” The pervasive nature of Canadian nationalism is such that we are asked to celebrate the Canadian military at nearly every major sporting event without thinking twice about it. Because the assumption is that we are doing good in the world. As we always have, right?

TM: Well, as your book shows, this is not the case! But still, I wonder, how concretely does public consent to the culture of Canadian imperialism get engineered? In Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of Mass Media, Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky (1988) (in)famously conceptualized the North American news media as a propaganda model that, as result of five interacting filters, works to manufacture the public’s consent to U.S. imperial policy. In Chapter 2 and elsewhere throughout the book, you present examples of Canada’s mainstream newspapers – The Globe and Mail in particular – parroting as opposed to probing the claims and statements of Peter Kent, the Minister of State of Foreign Affairs for the Harper Administration during the 2009 coup. Why do you think Canada’s leading newspapers mirrored Kent’s position on Honduras? How to explain this coincidence? In the context of the coup in Honduras, did the Canadian media operate as a “propaganda system” for the Canadian state and capital, manufacturing public consent to an elite consensus? Or were there examples of journalists acting as watchdogs of as opposed to lapdogs for power?

TS: On this question, I’ll only offer a tentative answer, since I haven’t done a systematic analysis of the Canadian media.

TM: No worries! Much more critical political economy research on the nexus of Canadian foreign policy and the news media as a propaganda model is needed.

TS: Yes, and my sense here is that the mainstream Canadian media has been more or less content to parrot the Canadian state on Honduras, largely out of self-imposed ignorance. The skeleton crews that represent most major news outlets can barely keep it together enough to provide critical coverage of local affairs, where experts are plentiful and critical analysis is easy to find. Media outlets don’t have desks in poor Latin American countries and I doubt there are more than a handful of people in the Canadian mainstream media who could say anything substantive about Honduran politics. As such, they rely on outside experts, and they aren’t inclined to go through the pages of the Socialist Register to find their experts! So, yes, the Canadian media replicates the Canadian government’s basic position and critical perspectives only come through once in awhile, without nearly enough weight or consistency to make a dent in public opinion.

TM: I wish Canada’s journalists would seek out the expertise of you, Greg Albo, Todd Gordon or Jerome Klassen when covering Canadian foreign policy. Unfortunate for the public sphere and democracy, they don’t. Instead, they rely upon sources controlled by the State (the foreign policy publicity apparatus) and capital (coin-operated foreign policy think tanks). When journalists tell us what to think about Canadian foreign policy (agenda setting) and how to think about it (framing), they are often being played by more powerful political and economic organizations. In Publicity and the Canadian State: Critical Communication Perspectives Kirsten Kozolanka (2014) and other researchers examine this problem. Now that I’m thinking about the dynamics of the publicity State and the propaganda model, I wonder: has your book taken any “flack” from the powers that be?

TS: Well, yes I certainly have had my fair share. The Winnipeg Sun took a go at me several years ago for daring to criticize the militarization of Canadian hockey culture, and I know from Freedom of Information requests that the Canadian government is reading my work. So, let me take this opportunity to say hi to the unfortunate CSIS bureaucrat who is reading this!

TM: I might as well say hi too given that some Big Data for Big Security State algorithm has likely profiled and linked me to you as a result of this interview. Anyhow, as research, your book conveys knowledge about the bad conditions that underpin Canada’s support for the military coup in Honduras. As praxis, it provokes readers to do something about these bad conditions. Did you have an intended audience in mind when writing this book?

TS: I think I’m writing this book to an audience of intelligent and critical-minded people who don’t know about Honduras but aren’t willing to blithely accept anything the Canadian government tells them. So, happily, that’s a lot of people.

TM: I hope so. What impact, then, would you like your book to have upon readers within and beyond Canada?

TS: The Canadian government has done a good job of helping the Honduran dictatorship stay out of the news. This book tries to put the story back in the centre of attention, and asks readers – especially Canadians – to grapple with the reality of what Canada is doing. I hope that it will galvanize support for the continuing resistance movement in Honduras, which desperately needs the rest of the world to pay attention.

“In 150 years, “Canada” has most often served the collective class power of the Upper Canada elite. I hope my book will help to pierce the armour of Canadian exceptionalism and better equip us to confront class power in Canada that sells itself to us as red mittens and Don Cherry.”

I also hope it will push people to re-think what it means to be Canadian, and here I’m speaking both to mainstream Canadian culture but also the left in Canada. We have to dispense with the myth that Canada always already means well. We have to forego the idea that democracy, freedom, or peace are essentially “Canadian values.” The Canadian State has consistently and often brutally stood against all of those things when the power of Canada’s corporate class was challenged. In 150 years, “Canada” has most often served the collective class power of the Upper Canada elite. I hope my book will help to pierce the armour of Canadian exceptionalism and better equip us to confront class power in Canada that sells itself to us as red mittens and Don Cherry.

TM: Well said. Discourses of Canadian exceptionalism are routinely mobilized by the Canadian Right and the liberal Left to whitewash history and transform the actuality of class inequality, conflict and struggle into a story of happy unity. More than ever, we need to interrogate how the sign of the Canadian nation is articulated to power, how it is mobilized to serve and obscure social class power in Canada, and possibly, do a better job of articulating this sign to progressive projects. This is a political challenge and a pedagogical one. Speaking of public pedagogy, on Thursday May 4, your book launched in Toronto at Another Story bookshop. The event was packed with colleagues, community members and students. You are a very popular professor! That said, naming, teaching and inspiring critical thinking in students about “Canadian imperialism” seems tough, especially given the myths that close the public mind to reality. How do you teach “Canadian imperialism”? How do students react to your teaching? Shock? Disbelief? Denial? Anger? Or, do students thirst for knowledge that debunks the myths of Canadian foreign policy? Can you recall any notable “teachable moments” for doing a pedagogy of Canadian imperialism?

TS: Actually, I find it quite easy to talk to students about this stuff. You really just have to respect people and know that they are all bringing ideological baggage into the classroom and that doesn’t make them stupid or immoral. When you start from there, and when you make sure that students (or any other audience for that matter) have space to work through these things on their own (including pushback, denial, disbelief, etc) then you just let the facts speak for themselves. I never teach a class on Canadian foreign policy with an expectation that everyone will accept my particular take on everything, and I start every class with the assumption that they do not. I present an unvarnished version of Canadian history, curated not from the perspective of the Canadian elite but, instead, from the standpoint of their victims. It means that they hear a completely different set of facts, stories, and opinions from the ones they are used to hearing, and it gives them an opportunity to compare those different versions of Canada.

So I welcome students’ honest reactions. I expect pushback and encourage it, and I ensure that students know they are respected, even if they disagree with something I’m saying. Some of my best students are the ones that enter the class really pumped up about Canada, because I allow students to develop their own critiques, interrogating the gap between what they are typically told about Canada and what I present to them. They’re smart people, and they often develop their own lines of critique that are every bit as sharp – sometimes sharper – than my own.

In my experience, students definitely appreciate the shattering of these myths. Most often, students express a sense of “I knew it was too good to be true” and, in fact, a confirmation of things that at some level they already guessed. This is partly a product of demographics, of course; I am not teaching at the University of Toronto or some other institution where I would be more likely to encounter a demographic that really is part of the Canadian elite. My students tend to come from demographics that would be more receptive to a critical take on Canada. For instance, I have had working-class Muslim students talk about the discomfort they feel at a Toronto Maple Leafs’ game when an arena full of people is cheering for Canadian soldiers in Afghanistan. So, in a way, I’m lucky: I get to learn from my students, whose analysis of these things can be more piercing and productive than my own.

TM:: Thank you for sharing these tips on best practices for doing a critical pedagogy of Canadian imperialism. Some of my pedagogy (and much of my research) centers on how the U.S. Empire mobilizes the cultural industries to produce war-glorifying militainment. Given my interest in the U.S. case, your book’s “Conclusion” intrigued me, as it highlights the Canadian military’s multi-million dollar PR budget and touches upon how effective the Canadian Forces is at embedding itself in professional sports, TV ads and even video games. “What’s to be done” about the creeping militarization of Canadian culture at the present time? How to respond to this trend?

TS: This is I think one of the major ideological battlegrounds in Canadian culture right now. I’m a hockey fan and I’m buried pretty deep in the culture of the sport, and there is a reason it has been chosen as prime ground for military culture. There are so many ways in which the dominant ideology in Canadian hockey chimes with the new Canadian militarism. The glorification of violence, the constant assertion of Canadian superiority, the deeply patriarchal culture, and so on. At the same time, when you dig beyond the surface, there are a lot of hockey fans who have the capacity to be smart and critical.

TM: But how can progressives reach these savvy fans and attract them to a better politics?

TS: I think there is some value in being connected to cultural institutions like hockey, in order to push a different line within that culture. Here, as anywhere, you have to earn people’s respect if you want to open their mind to a different perspective. So, for me, that means knowing the game, understanding its culture, and respecting people within it. That way, when I say “Don Cherry shouldn’t be using his pulpit to promote the military” people might listen, because they know that I also think the offside challenge is a stupid rule, Malkin is an underrated superstar, Vancouver needs to trade Tanev, and the NHL needs to take head injuries seriously.

TM: This is really helpful advice, and it kind of brings to mind what the late but great Stuart Hall (1981) said about the significance of popular culture to socialist struggles in his important essay, “Notes on Deconstructing ‘the Popular’.” Between the notion of popular commercial culture being either a manipulative instrument used by capitalist elites to ideologically brainwash the masses or a direct expression of working class experiences, Hall conceptualized popular culture as a site of struggle for and against socialism: “popular culture is one of the sites where the struggle for and against the powerful is engaged. It is partly where hegemony arises, and where it is secured.”

TS: Exactly! We need to be in these cultural institutions, battling against the creeping militarization and other manifestations of right wing politics like Islamophobia through popular culture. It’s hard work. It means engaging with people, disagreeing with them, challenging them. But it is very important, especially in a moment of surging far-right politics, to build the ideological base for progressive politics. And you can’t do that by hiding in a university tower writing articles that seven people will read. You have to be in the world, dealing with people, making clear arguments, speaking plain language.

I hope this book will help us to do that. I hope it provides some of the information and analysis we need to go back into the cultural and political institutions of this country and win people back to progressive politics.

TM: Well, Tyler, your book is a vital resource in this regard. I will surely return to it in my teaching and research in the years to come. Thank you so much for doing this interview, and I look forward to reading and learning more from you in the future. •

References

- Gordon, Todd. 2010. Imperialist Canada. Winnipeg: ARP Press.

- Gordon, Todd, and Jeffrey R. Webber. 2016. Blood of Extraction: Canadian Imperialism in Latin America. Blackpoint: Fernwood Publishing.

- Hall, Stuart. 1981. “Notes on Deconstructing the Popular.” In People’s History and Socialist Theory, edited by Raphael Samuel, 227-41. New York: Routledge.

- Herman, Edward, and Noam Chomsky. 1988. Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. New York: Penguin-Random House.

- Kellog, Paul. 2015. Escape from the Staples Trap: Canadian Political Economy After Left Nationalism. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Klassen, Jerome, and Greg Albo, eds. 2012. Empire’s Ally: Canada and the War in Afghanistan. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Klassen, Jerome. 2014. Joining Empire: The Political Economy of the New Canadian Foreign Policy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Kozolanka, Kirsten, ed. 2014. Publicity and the Canadian State: Critical Communication Perspectives. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Mirrlees, Tanner. 2016. Hearts and Mines: The US Empire’s Culture Industry. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Said, Edward. 1993. Culture and Imperialism. New York: Vintage.

- Shipley, Tyler. 2017. Ottawa and Empire: Canada and the Military Coup in Honduras. Toronto: Between the Lines.