“Restore our democracy” has become a mantra among American progressives. Populist writers are desperately trying to shake people from their passivity amidst mounting political and ecological crisis. But in crafting a vision of a better future they often appeal to idealized, romantic notions of America’s past.

Chris Hedges recently attributed the rise of Donald Trump to a “corporate coup” that happened “more than two decades ago,” leaving Trump in command of a state devoid of meaningful democratic input or checks – a situation he refers to as “fascism.” His antidote is the Green Party, whose leaders Ralph Nader and Jill Stein “saw this dystopia coming” but were foiled by “elites” and “so-called progressives” who “succumbed to the idiotic mantra of the least worst.” Similarly, Bernie Sanders’s recent op-ed in the New York Times ends with a call for the Democratic Party to “break loose from its corporate establishment ties and, once again, become a grass-roots party of working people, the elderly and the poor.”

These kinds of interpretations rely on naive civics-textbook notions of the history and workings of the American state; they support political strategies of either reforming the Democratic Party or voting for the Green Party, while concealing the shortcomings these approaches entail.

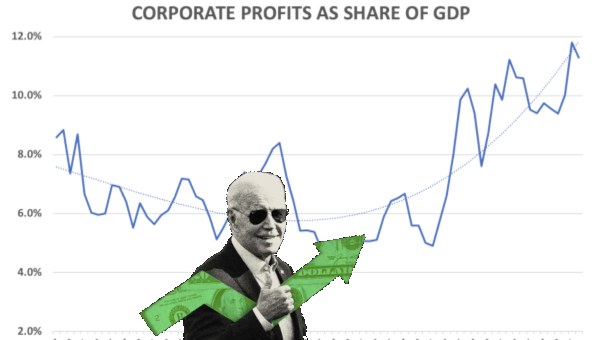

Looking back over American history, it is clear that no “corporate coup” has taken place. The American state is a capitalist state and has been since at least the late nineteenth century. Indeed, in some respects, the state is more democratic than it has been at many points in the past.

Still, Trump’s far-right nationalist chauvinism could present capital with a far-right path to cope with the crisis of neoliberalism. At base, the rise of Trump’s authoritarian populism is the result of the social dislocations wrought by thirty years of neoliberal devastation visited upon working-class communities. But it is also a consequence of the failure of the Left to formulate a credible transformative strategy – a failure evident in the ahistorical romanticism of Hedges and others.

The logic of “Make America Great Again” must not be countered with more nostalgia. We need a bold vision for the future that honestly accepts the uncertainties it entails.

Neoliberalism: A Corporate Coup?

It is easy to understand why populists, on both the right and the left, rely on an idealized American past in laying out their vision for the future: it makes the struggle ahead appear more realistic – as simply regaining what we once already had rather than pursuing an untested utopian vision. But getting somewhere better will require an honest assessment of the structures of U.S. power.

The idea that neoliberalism is the result of a “corporate coup” echoes the classic “pluralist” view of the American state which dominated mainstream scholarship from the 1960s until it was decisively refuted by neo-Marxist state theorists Ralph Miliband and Nicos Poulantzas in the 1970s. According to the pluralists, competing interest groups – including business and labor – organize themselves within “civil society” to influence a passive, neutral state. Power is polyarchic, with no one group dominating the “political system.”

Populists assume that this system worked more or less as advertised until a few decades ago, when corporations’ superior organizational cohesion and command over resources allowed them to essentially take over the state, corrupting an otherwise ideal liberal democracy.

This framework is a fantasy. The American state is a capitalist state whose function is and has been to organize the political hegemony of the capitalist class. Since individual capitalists are motivated by the pressures of competition rather than broad class-wide concerns, a relatively autonomous state is needed to secure the long-term interests of the system as a whole.

The historical trajectory of the American state demonstrates this role. The U.S. state has played a dynamic and active role in politically organizing corporate power – the opposite of the pluralist view assumed by the populists. This has included playing a leading role in forming “lobby” groups like the Chamber of Commerce and Business Roundtable. Liberals often assume these entities organize themselves and act upon the state independently, but this is a misreading of history.

The modern American state began to take shape in the late nineteenth century, a process that corresponded with the organization of large bureaucratic corporations. Though its initial weakness forced it to rely upon bank-dominated cartels and trusts to stabilize highly volatile markets, state capacities steadily expanded, evidenced by the establishment of the Interstate Commerce Commission in 1887 and the Department of Commerce and Labor in 1903.

Granted, those staffing the new commerce department quickly found that their lack of resources and capacities required them to rely heavily on the input of bankers and corporate managers, who they sought to integrate within the policy-making process by facilitating the organization of the Chamber of Commerce in 1912. But as the state grew stronger, its ability to play a proactive and independent role in organizing capital was steadily enhanced.

By the New Deal period, the U.S. state was strong enough to intervene to reduce bank power within corporate governance systems, empowering internal managers instead. Amid the most severe capitalist crisis to date and intense class upheaval, Roosevelt established the Business Advisory Council by executive order. Made up of top executives from the nation’s largest firms and funded by corporate donations, the BAC became a valuable tool to organize support for the massive deficit spending and institutional expansion Roosevelt deemed necessary (even though he found the body “useless from the point of view of facts and policies”).

The need to produce war material led the state to deepen coordination with the largest manufacturing firms, administered by the War Production Board and later the Office of Defense Mobilization. General Electric CEO Charles Wilson (or “Electric Charlie”) became so powerful in his position at the head of the ODM that the press referred to him as the “co-President.”

But the state’s function of organizing capital was by no means limited to periods of crisis. Despite the “de-control” of private enterprises after the war, the emergence of a state-capital institutional complex comprised of the leading state agencies and the largest corporations, now multinational in scope, was unmistakable. The development of new technologies for military and consumer purposes required greater integration among state agencies, universities, and corporations – a process planned and encouraged from within the state defense and science policy apparatus. The most dynamic corporations have continued to rely heavily on this state-led “innovation system,” spinning off technologies paid for by taxpayers into consumer and industrial products.

Later, the abject failure of Nixon’s and then Carter’s wage and price controls to break the 1970s inflation crisis by disciplining workers into accepting wage restraint brought a need for new ideas. It was within increasingly prominent agencies like the Treasury and Fed that a resolution was devised, based on integrating global financial markets and internationalizing production to break the power of unions and restore profitability. Coordinating internationally integrated production networks also meant empowering finance, which became increasingly politically and economically hegemonic as institutional barriers to the movement of value were dropped.

Developing a framework wasn’t enough: these agencies also needed to organize capital in support of it. This occurred most prominently with the formation of the Business Roundtable in 1972 at the encouragement of Secretary of Treasury John Connally and Federal Reserve chairman Arthur Burns. In the end, the roundtable succeeded in building a consensus among the most significant representatives of the capitalist class around the neoliberal framework largely advanced by Treasury and the Fed.

The tilt of the Democratic Party toward neoliberal reforms must be understood in this context, as a consequence of what James O’Connor identified in the 1970s as a “fiscal crisis of the state.” The sustainability of state spending on social programs was always dependent on long-term growth. When this slowed, a fiscal crisis emerged which, in the context of inflation, could only be resolved by increasing taxes or making cuts. Democrats pursued the latter choice. And as the globalization of production and corporate attacks weakened the labor movement, workers were increasingly unable to mount any serious opposition.

In short, the neoliberal variant of capitalism was not the result of a a “corporate coup.” It is the result of the familiar, systematic workings of a capitalist state seeking to resolve a crisis and restore the system to “health.”

Trump’s Rise

However, to say that the last thirty years of neoliberal policy were not simply the result of a “corporate coup” does not mean that Donald Trump is simply a “boilerplate” Republican. If he were, how could we explain the tremendous fight the GOP establishment waged against him?

Trump did not receive a single donation from a Fortune 100 CEO, while a broad range of top military brass and establishment Republicans – including George Bush, Mitt Romney, Colin Powell, Paul Ryan, Hank Paulson, Bill Kristol, and others – either endorsed Clinton or suggested they couldn’t support Trump. All this indicated a wide-ranging consensus among the capitalist class behind Clinton, founded upon maintaining the status quo abroad (“free trade” and militarism) and multicultural pluralism at home – a consensus which involved rejecting Trumpism as unacceptable.

But in the face of the delegitimization of neoliberalism, and the crisis of the state that has accompanied it, people did precisely what mainstream elites told them not to do. They elected Trump.

Yet Trump’s victory was hardly a bolt from the blue. Neoliberal restructuring laid the administrative, institutional, and social groundwork for the emergence of his authoritarian populism, including the erosion of liberal democratic institutions, the concentration of state power in the executive, increasing precarity and middle-class decline, and the delegitimization of the media system and state mechanisms of political representation.

Key state agencies – especially the Federal Reserve – have been carefully insulated from democratic oversight that could corrupt their “technocratic” management of competitive markets. Indeed, central bank “independence” and regulatory “autonomy” have been central to the neoliberal program for state reorganization.

Similarly, what Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin call the “internationalization of the state” has further concentrated power in these agencies and hollowed-out democratic institutions. Over the past three decades these agencies have become deeply entangled with transnational institutional regimes established through “free trade” agreements. These agreements effectively “constitutionalize” neoliberalism, locking states in to protecting corporate and investor rights against the environment and labor, regardless of the will of the population.

The rise of the Clintonite–Democratic Leadership Council wing of the Democratic Party cemented bipartisan support for the neoliberal variant of capitalism, a political expression of both the corporate consensus and the weakness of labor. And since, as Chomsky and Herman have shown, the corporate press is systematically confined to the range of elite political views, this neoliberal consensus was hardly contested within mainstream discourse.

But dissatisfaction with the elite consensus was by no means eliminated. It was registered first from the right in the form of the Tea Party, which emerged in consequence of the decades of hollow nationalism emanating from the GOP that did little to improve the lives of its “base.” But the 2008 financial crisis created an opening for the Occupy movement to promote a more progressive narrative of class struggle, illustrating the failure of both parties to present meaningful alternatives to increased working-class indebtedness and precarity. This sharply accelerated the delegitimization of neoliberal ideology, both political parties, and the media system.

In the run-up to November’s election, this crisis was on full display. While Bernie Sanders was suppressed and sidelined by the Democratic Party, Trump found fertile ground to articulate and nurture the popular anger and anxiety that accompanied these huge structural changes but could not find expression within hegemonic political discourse. In conditions of typically low turnout – 50 percent of the country did not vote at all – Trump was able to assemble enough of a base, mostly white men, to win the election.

A Risky Gamble

The electoral success of Trumpism has offered capital a tempting new ideological means to cope with the legitimacy crisis of the state: an authoritarian populism that can enable hard-right market-building policies, but which also provides space for the mobilization of fascistic political movements.

Yet, the incoherence of Trump’s policy paradigm – in some ways contradicting neoliberal capitalism, in others reinforcing it – makes it a risky gamble for a capitalist class seeking to hold the neoliberal project together despite mounting contradictions. Moreover, given the American state’s indispensable role in “superintending” global capitalism, the possible impact of Trumpism on its ability to manage and contain economic crises is also a serious concern.

The key question for capital is the degree to which it is willing to accommodate Trump’s extreme nationalism, which may threaten the international economic integration that has been central to the neoliberal project. But despite the widespread opposition of the capitalist class to Trump’s electoral bid, capitalists appear to be discovering that they can work with Trump.

For his part, Trump is clearly trying to appeal to dominant sectors, especially finance. As one Goldman Sachs executive recently put it, “If I’d have known how good Trump was going to be for Wall Street, I’d have campaigned for him.” The executive was referring to Trump’s emerging policy agenda, which has also triggered what market analysts are calling a “Trump rally” as the S&P 500, Dow Jones, and Nasdaq indexes all hit record highs in the weeks after the election.

That Trump seems ready to take up the regulatory agenda of the financial sector indicates how unlikely it is that his isolationist rhetoric will be reflected in the erection of barriers to the free movement of capital that has been the hallmark of the post–World War II American empire. Instead, Trump’s statist authoritarianism – restrictions on immigration, intensified policing of poor people, and a crackdown on internal dissent – will likely go hand-in-glove with market-oriented restructuring.

Famed Keynes biographer and political economist Robert Skidelsky recently compared Trump to the fascist regimes of the interwar period, suggesting that “Trumpism may be a solution to the crisis of liberalism.” This is particularly true if he is able to resume economic growth by implementing his promised $1 trillion infrastructure expansion program which Senate Democrats have indicated they may be willing to support. This could help solidify his base and earn him support from broader segments of both capital and labor.

It would also follow in the footsteps of European fascist regimes of the 1930s, which were organized by capitalist classes who had no other path out of crisis. By foreclosing democratic institutions, these regimes were able to protect the power of capitalist classes by implementing policies only possible under conditions of extraordinary state autonomy. Hitler was a great Keynesian.

But Trump’s economic program will not be carried out in twentieth-century Weberian bureaucratic fashion. It will bring not the return of Keynesian macroeconomic management, but rather the expansion of market mechanisms.

Trump’s infrastructure program, if implemented, will be market-centered and conducted through “public-private partnerships.” This would create massive state-subsidized investment opportunities for Wall Street in privatized public infrastructure, which can remain a stable source of profits long into the future – similar to the program currently being carried out by the Trudeau government in Canada.

Moreover, far from enlarging welfare state protections that could redistribute wealth and strengthen labor, these policies will be accompanied by tax cuts and the further marketization of social services, including Medicare and public education. This will result in the upward redistribution of wealth and larger deficits – the latter of which can later be used politically to further impose austerity.

But Trumpism – now amplified by the state apparatus and increasingly “normalized” – will certainly open space for the neo-fascist right to mobilize and build. The discursive power of the presidency to frame reality has diffuse, decentralized social effects, forming a lens through which people see and understand the world around them – instigating and encouraging dynamics and logics that appear to emerge “from below.” And if he fails to deliver, his regime is likely to move to the right, a scary prospect indeed.

So even if Trump’s rhetorical bluster becomes simply another way to implement familiar economic policies, these will have taken on an alarmingly authoritarian and chauvinistic ideological apparatus to support them. The foundations of neoliberalism have included right to individual self-expression, pluralism, multiculturalism, freedom of the press, and so on – all things Trump has expressed strong antipathy toward.

“As Trumpism is “normalized” within the state ideological system, the taboos that led capital to initially eschew Trump are broken and the political culture changes.”

Given this, the degree to which the political-discursive shift represented by Trumpism could be called “liberal” in any sense is strongly in doubt. If Trumpism is a liberalism, it is one that has given up on most limits on state infringement upon individual freedoms in order to protect the power of capital. As Trumpism is “normalized” within the state ideological system, the taboos that led capital to initially eschew Trump are broken and the political culture changes.

Indeed, though the political conditions may not quite resemble those of 1930s Germany, one should not underestimate the suddenness with which liberal institutions – dependent to a tremendous extent not merely on formalized processes but also an informal “political culture” – may deteriorate.

While it appears Trump is ramping up for a massive voter suppression effort, the extent to which he may be willing and able to discard constitutional protections is deeply frightening. David Clarke Jr, who has been interviewed for the job of Homeland Security Secretary, has suggested subjecting up to one million Americans deemed “enemy combatants” to military tribunals and detention. He has also publicly argued that the Black Lives Matter movement “will join forces with ISIS.”

As internal dissent is increasingly labeled in this way, the reactionary statism of Trump and those around him could take on terrifying dimensions. This is especially so given that Obama has left Trump a state with power more concentrated in the executive than ever before. This includes a vast, secretive intelligence-security apparatus increasingly beyond institutional constraints like judicial oversight.

The 2012 National Defense Authorization Act signed by Obama authorizes the indefinite military detention of American citizens deemed “terrorists” by the president without a shred of due process. The act was later amended to assert the right of the president to maintain secret “kill lists” of those (including U.S. citizens) to be targeted for death without charges or trial – so long as they are not on American soil. What will these powers mean for President Trump?

No Nostalgia

The lesson is clear: we cannot simply “restore our democracy” by voting for either the Green Party or the Democrats. Only a strong, class-based movement capable of clarifying the causes and consequences of neoliberal capitalism can defeat the Right and put a progressive break with the political and economic program of the past thirty years seriously on the agenda. Moreover, only a party grounded in such a movement has any real hope of capturing and transforming the state.

For Hedges, the answer is easy: vote for Jill Stein. But this fails to offer a convincing explanation for why the Greens have been unsuccessful. The simple truth is that the Green Party has forsaken the kind of organizing necessary to build a serious base in favor of presenting the “right” arguments every four years, when they suddenly appear to contest presidential races.

This strategy assumes an ideal liberal conception of the state: that elections are expressions of the democratic will of the population, in which she who makes the most persuasive case wins. Moreover, without the support of a broad social movement or party structure, it is almost unthinkable that a single individual placed in the White House could do much.

Sanders’s call to return the Democratic Party to an earlier state as a mass people’s party is equally fanciful. Though democratic institutions have been hollowed out in the neoliberal period, the role of the state has always been to organize the capitalist class. Moreover, the expansion of the New Deal welfare state in the postwar period, and the rising standards of living associated with the “Golden Age” of capitalism that lasted until the 1960s, were the result of class struggle and unionization, not an imagined mass-popular character of the Democratic Party that has somehow disappeared.

Seriously contending with the looming social, ecological, and political crises – and the potentially rising neo-fascist tide that threatens to worsen them – means doing much more than restoring an idealized American democracy. Nor is it enough to simply beg people to vote for the Greens in the hope that somehow this will eventually build “on its own” to a level where Stein (or whomever) has a chance to win office.

Instead we need to organize a socialist movement from the ground up that cannot simply be sucked into electing establishment Democratic candidates every election cycle. This is where the conversation needs to begin – a conversation that progressives are still largely failing to seriously engage in. •

This article first published on Jacobin website.