Saskatchewan Party leader Brad Wall has earned a major place in Saskatchewan’s political history. On April 4 he broke the back of the NDP, the province’s “natural governing party” since 1944. Until Wall’s first victory in 2007 the CCF/NDP ruled the province, suffering only two interruptions. Liberal Ross Thatcher defeated Woodrow Lloyd’s CCF in 1964 and 1967, only to be crushed by Allan Blakeney’s NDP in 1971. Tory Grant Devine defeated Blakeney in 1982 and 1986, only to be wiped out by Roy Romanow’s NDP in 1991. Until Wall’s victory over Lorne Calvert’s NDP in 2007 the CCF/NDP ruled the province for 46 years from 1944 to 2007. Both Thatcher and Devine became minor footnotes in Saskatchewan’s history. Wall will not suffer this humiliation. He made history by winning a third term.

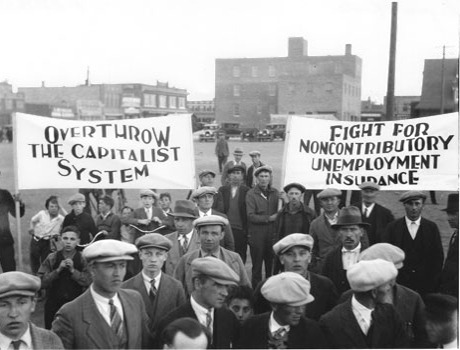

Wall did not just win an election in April. He accomplished what political scientists call a “structural realignment” in the electoral coalitions of the province. The last time this happened was in 1944 when, from 1932 to 1944, the Farmer Labour Party and then the CCF carefully fashioned an unprecedented coalition around a socialist program uniting the province’s middle class farmers with the urban working class. T.C. Douglas’ majority was won in rural Saskatchewan, where elections were won or lost in 1944, as a majority of farmers voted socialist. The CCF’s support among the urban working class turned that majority into a sweep of the province. This farmer/labour electoral coalition, due to its inherent fragility, was carefully tended by the CCF/NDP and lasted well into the 1970s, becoming the foundation of the party’s long success.

Wall did not just win an election in April. He accomplished what political scientists call a “structural realignment” in the electoral coalitions of the province. The last time this happened was in 1944 when, from 1932 to 1944, the Farmer Labour Party and then the CCF carefully fashioned an unprecedented coalition around a socialist program uniting the province’s middle class farmers with the urban working class. T.C. Douglas’ majority was won in rural Saskatchewan, where elections were won or lost in 1944, as a majority of farmers voted socialist. The CCF’s support among the urban working class turned that majority into a sweep of the province. This farmer/labour electoral coalition, due to its inherent fragility, was carefully tended by the CCF/NDP and lasted well into the 1970s, becoming the foundation of the party’s long success.

Changing Demographics, Changing Class Compositions

The bricks for Wall’s structural realignment were laid from the 1970s to the 1990s. The class structure of rural Saskatchewan changed dramatically, characterized by a rapid growth of larger and larger farms, whose owners developed a clear market-oriented/capitalist ideology, and a rapid decline of middle level farmers, the rural base of the traditional CCF/NDP coalition. The successful challenges from the Liberals in the 1960s and the Tories in the 1980s ate away at the party’s rural electoral base. As the NDP’s rural base shrank, with ebbs and flows, its urban base grew. Accelerated rural depopulation increased the weight of the urban vote, enhancing the political significance of the NDP’s solid urban working class base. The NDP’s traditional coalition was in crisis as NDP support in rural areas began to disintegrate while the importance of its urban base increased.

NDP Premier Romanow made a fatal strategic error in the 1990s when he wrote off much of rural Saskatchewan as hostile territory for the NDP, tying the party’s electoral future to a primary focus on its urban bastion. Rural Saskatchewan received careful attention only in certain areas, especially those with significant smaller urban centres, in order to win the handful of rural seats necessary to win majority governments. Romanow’s second strategic error was to abandon social democracy and embrace pro-capitalist neoliberalism, turning his back on the party’s raison d’être since 1932. When the CCF arrived on the scene the province’s politics deeply polarized between the left-leaning, democratic socialist CCF and the pro-capitalist Liberals and Tories.

The failure of the Liberals and then the Tories to fashion a permanently successful right-wing, pro-business, anti-CCF/NDP electoral coalition led to the founding of the Saskatchewan Party (SP) in 1997, for the first time uniting the province’s right-wing in one party. This ongoing ideological polarization between the social democratic NDP and the right-wing pro-business option kept the province’s politics vibrant and the electorate deeply engaged. The decisive victories of Blakeney in 1971 and Romanow in 1991 resulted in no small measure from this ideological polarization. Voting actually meant something in those days.

When Romanow won in 1991, like Blakeney in 1971, he promised a return to social democratic principles and the reversal of the neoliberal excesses of the Devine years. But in an act of disillusioning betrayal, upon victory Romanow embraced neoliberalism and continued its remorseless implementation. When Romanow crashed in 1999, almost losing to the SP, he was able to cobble together a coalition with two Liberals MLAs to stay in power. He resigned in 2001. In his successful campaign for leader Calvert distanced himself from the Romanow years, called the discouraged and disillusioned home to fight the good fight, and promised a return to basic social democratic principles. Calvert won a hotly contested, polarized election in 2003, an election everyone expected him to lose. But upon winning his own mandate as premier, Calvert reverted to the now hegemonic position of the federal NDP and all other provincial sections of the party – qualified, critical support for neoliberalism.

Institutionalizing Neoliberalism

The stage was set for Wall’s march to power. The contest was now between two neoliberal parties with nothing of substance distinguishing them. The question became who could administer a pro-business, non-interventionist government and manage a capitalist economy most successfully: the NDP, promising neoliberalism with a human face and compassion, or Brad Wall who, unlike his predecessor Elwin Hermanson, promised the same compassion combined with an enthusiastic commitment to grow the economy to unprecedented prosperity. The NDP never stood a chance. The NDP was already shut out of rural seats, where Wall enjoyed easy sweeps. The focus was therefore on the NDP’s urban seats: the SP took 3 of 27 in 2003; 10 of 27 in 2007; 20 of 27 in 2011; and 22 of 30 in 2016. The NDP was dead in rural areas, where the SP routinely won seats with 70 per cent. The NDP’s urban base is now a shambles. Wall’s structural realignment is much more decisive than that of Douglas in 1944. During its years as the natural governing party the CCF/NDP won over 50 per cent of the vote in four elections (1944, 1952, 1971, 1991). The SP under Wall has already won three (2007, 2011, 2016) – the last two with over 60 per cent, something never achieved by the CCF/NDP.

Wall came to power as a Sunshine Premier – things were already pretty good and he promised to make them better. He would grow the economy and make Saskatchewan stronger. The province’s resource economy, already doing well, began to boom. The NDP had cleaned up the Devine mess; established fiscal stability; balanced budgets; trimmed social programs; implemented all the tax and royalty concessions demanded by business; kept the lid on labour rights; and socked away $2-billion in a fiscal stabilization fund for rainy days. Things only got better under Wall, as he presided over the most sustained economic boom in recent history: potash hit $900/tonne in 2008; uranium $70/lb in 2011 and oil $107/barrel in 2014. Money poured into the provincial treasury and Wall spent it on increased program spending and cutting taxes even further. Wall spent like it was a never-ending boom.

The boom began to bust, as resource booms inevitably do. By 2016 oil had fallen to $26; potash to $300; uranium to $26. Experts predicted poor demand and low prices for all three until at least 2020. Wall staved off the worst of the impact by running up deficits, heavy borrowing, emptying the stabilization fund, and ransacking the Crowns for increased revenues. He successfully hid the full extent of the bad news, gaining his history-making third term in April.

The next chapter in the Sunshine Premier’s political story will be quite different, putting to test the resilience of the structural realignment in voting behaviour Wall so successfully fashioned. •