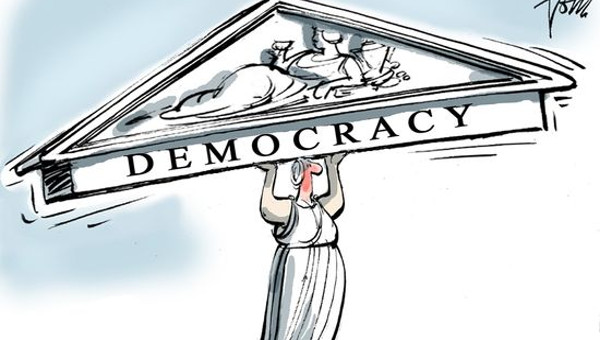

There is no doubt that the near majority obtained by Syriza in the elections last month represent a point-of-no-return for Europe. This is the result most feared by the rulers of several countries and, above all, by the financial powers that have undertaken an intense campaign of threats, based on the idea of an increasingly liberal Europe, according to which a victory by Syriza would endanger stability and (purported) economic growth. But it is also the most desirable result for those who have a different conception of Europe, one of solidarity and democracy instead of competition and of decisions coming from on high – ‘Another Europe’ of social justice and popular participation that in recent years has become increasingly difficult to believe in.

Beyond the internal and external challenges that will confront the Alexis Tsipras government, and beyond the reaction that will come from the political-financial authorities, the electoral campaign and its conclusion already provide some helpful ideas in attempting to construct an idea of Another Europe.

Beyond the internal and external challenges that will confront the Alexis Tsipras government, and beyond the reaction that will come from the political-financial authorities, the electoral campaign and its conclusion already provide some helpful ideas in attempting to construct an idea of Another Europe.

There is undoubtedly, above all, a clear sign of rejection of the arrogance of those who presently govern Europe – indifferent as they are to every warning coming from the citizens of Europe. Indifference to the indicators of an EU in a very deep crisis of legitimacy; to the dramatic collapse of trust in its institutions from 2008 to the present; to the two-thirds of European citizens for whom Europe evokes negative sentiments; to the elections that have above all punished the kindred members of the European People’s Party. The

institutional response has been to continue with the politics and policies, which have not only become unpopular, but also ineffective.

No More Fear

The results of the Greek elections testify to the fact that, increasingly, the high-handed diktats from national and international financial institutions – most recently from the Bundesbank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) – no longer elicit fear, but rather indignation at the violation of every semblance of democracy and national sovereignty, as well as for their obvious failure to deliver the promised but perpetually elusive economic growth. The rejection is all the stronger the more the increasingly opaque powers – the various Troikas, Eurogroups, or indeed, banks – demand from the poorest countries not only the implementation of strict budget standards, from which the most powerful countries get a pass, but also the imposition of ‘reforms’ (i.e. deregulation of labour markets, dilution of worker rights, reductions in social services) whose efficacy no one has yet proved.

In a situation of humanitarian emergency, the threats coming from these institutions have not produced submission, but rebellion. In contrast to the arrogance considered by many to be illegitimate and ineffective, Greeks have voted in majority for a party that is not Eurosceptic, but that proposes a different vision of Europe. Apart from the election results, with support for Syriza greater than expected though not such as to guarantee an absolute parliamentary majority, the aspiration for Another Europe originates from the

process that was started in 2011 and continued on to 2015. The discourse of fear coming from governments and financial institutions was counterposed with a discourse of hope – pragmatic in the demand of rebuilding the minimal conditions of well-being and democracy, but also with regard to breaking with the policy evolution of recent decades. Throughout this process the importance was

confirmed for the left of maintaining a connection between social movements and political (i.e. party) representation in the defence of rights that rulers have defined as out-dated, but which citizens still consider essential. This is a message that goes beyond Greece, as does the passion and enthusiasm that these elections have sparked on the left, above all in southern Europe.

Turning Point for the European Left

From this perspective the elections in Greece are also a turning point for the European left. Of course it remains to be seen to what extent these

positive emotions for a first victory on the left against austerity can transform into an alternative project in the various European countries, which without copying Syriza, is able to build a winning strategy on the streets, but also inside institutions.

What is certain is that, unexpectedly, precisely when institutional opportunities seemed the most closed to social movements opposing austerity policies and demanding social rights in Greece, but also in Spain, political parties connected in different ways to innovative, dynamic and successful social movements, have emerged after the defeat of centre-left parties – who moved rightward – but also of

the far-left remnants of the past. In Greece and Spain government handling of the crisis produced the collapse of the centre-left parties, which lost members and voters. For the first time opportunities to govern are opening for new parties of the left – radical but pragmatic, not populist but aimed at creating a popular vision that is not Eurosceptic but interested in the idea of Another Europe. If a positive project for Europe can be revived, it will begin with these new seemingly non-ephemeral forms for demanding civil, political and social rights. •

This article was originally published by sbilanciamoci.info and Il Manifesto.

Translation by Sam Putinja.