The Turkish Uprising of May 27, 2013

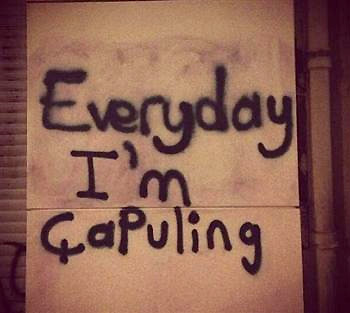

When the Turkish Prime Minister Tayyip Erdogan called the protesters in the streets of Istanbul plunderers (çapulcu) on June 2, he contributed a new verb to the English language. A video clip of the resistance – entitled “Everyday I’m Chapuling” – hit the internet on June 4 with new lyrics written on the pop song “Everyday I’m Shufflin.” And the new English verb was born: to chapul. Soon after, the word moved to the French language and found a place among such words as liberté, egalité and fraternité: chapulité.

The international media have been covering the events of the ongoing uprising that started on May 27 extensively. This article focuses on the reasons behind it as well as on potential outcomes.

The Justice and Development (Adalet ve Kalkinma or AK) Party (AKP) took power in 2002. A darling of Western governments and media until recently, it won three elections in a row, getting about fifty per cent of the votes in the last election in 2011.

Now, the AKP has more than 66 per cent majority in the national assembly, which allows them to pass any law they please; they have the entire police force, which allows them to arrest or suppress anyone they want; they have the entire justice system, which allows them to prosecute whomever they like; they control the Turkish military, which allows them to dream about regional hegemony Ottoman style. And, they control all economic and financial institutions from the Finance Ministry to the Central Bank to shape the economy in their own image irrespective of the needs of the population.

Model of Democracy

The AKP has been presented by the Western media not only as a democratic model for the Muslim world but also as an economic model for Europe during the ongoing global financial crisis. While the austerity based economic model of the AKP has been nothing but a neoliberal speculation and finance-led growth model of development familiar to Indians, what their “Muslim democracy alla turca” means suddenly has become clear even to the Economist, although the Economist itself introduced the concept only two years ago with high praise.

The obvious injustice and police brutality in Gezi Park was just the last drop in a long process of accumulation of discontent against this authoritarian government. Through their social policies, the AKP has been pushing for a conservative Islamic life style threatening in particular women and youth, criminalizing and imprisoning oppositional groups ranging from seculars to Kurds, socialists, and trade unionists. And through their economic policies, the AKP has been imposing their neoliberal agenda by increasingly commercializing public services, creating areas of rent for large corporations, and eroding the living standards and security of a significant part of the working people.

Their growth model depends on cheap labour, and speculative financial capital inflows and a high trade deficit. The share of industrial production is decreasing and becoming increasingly more dependent on the imports of intermediate and capital goods as well as energy. The agricultural production is about to go extinct and even the well-liked Turkish kebabs are now grilled with imported meat from such far away places as Argentina.

The AKP economic miracle of the past decade has risen on two pillars. First, pumping consumption through excessive credit. Second, rent extraction through privatization of the commons from land to public enterprises and natural resources. Neither of these strategies is sustainable and the unemployment rate is above 20 per cent among the youth.

Further, not only the households are in debt up to their neck but also the corporate sector. Although the AKP takes pride in having paid the last installment of its debt to the IMF, Turkey has borrowed increasingly more in the international financial markets during their reign, shifting the foreign debt burden from the public to the private sector. The foreign debt of the private sector has reached such unforeseen levels that Turkish corporations are now vulnerable to currency shocks that may lead to collective bankruptcies.

Rebellion On Many Fronts

Although the Western media present the Turkish Uprising of May 27 only as a rebellion against lack of democracy, nothing can be farther from truth. No doubt this is a rebellion against lack of democracy, voice and representation. But it is also a rebellion against rising inequality, unemployment and the private provision of basic needs as well as against the energy, ecological and food crises and the climate change.

The people in the streets come from many walks of life, age groups (although youth are on the frontlines), religions and ethnicities, and ideologies. There are anarchists in the streets, socialists, ecologists, nationalists, Kemalists, apolitical folks and even some voters of the AKP. Although the labour movement joined the protests with two strikes – the Confederation of Public Workers’ Union Strike of June 4 and 5, and the Confederation of Revolutionary Workers’ Unions Strike of June 5 – there is no massive participation of the Kurdish movement yet.

So, what can be the outcome of the uprising of such diversity with no set of concrete demands?

Perhaps Roger Waters of Pink Floyd in a letter to the protesters in Istanbul answered the question best.

“Your great country stands at the gateway between east and west. Constantinople is legend in the history of civilization. Your resistance today may well be a turning point between all of us and a return to the dark ages.”

Let us hope so. •