The Decline and Fall of an Old Preamble

(or A Social Democratic Party Becalmed)1

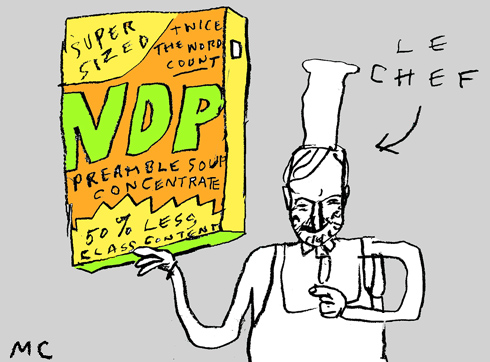

Like the federal Liberal Party leadership race, the NDP policy convention this past weekend proved to be rather anti-climactic. Any expectations (or hopes) for a divisive, soul-searching, battle royale over the identity of the NDP fell flat. With minimal debate and a decisive vote of 960 to 188, delegates approved a new preamble to the party’s constitution based in part on Jack Layton’s final message to Canadians and removed forward looking references to “democratic socialism” and “social ownership.” Instead, the new preamble lists the “social democratic and democratic socialist traditions” as part of the party’s heritage and calls for “a rules based economy” (for both the old and new preambles, see the end of this article).

A Long History of CCF-NDP Modernization

This was not a so-called Clause IV moment. In 1995, the British Labour Party, under Tony Blair, amended its constitution to remove the Clause IV reference to the goal of “the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange.” This wording dated back to 1918 and party members had beaten back the previous attempt in 1959-60 to amend Clause IV. Blair’s success in 1995 was clearly a significant step in the transformation of Labour into a “Third Way” party, distinct from post-war social democracy.

The Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) (the precursor to the NDP), actually had its own Clause IV moment way back in 1956, when it replaced its Regina Manifesto of 1933 and its stirring declaration that “No CCF government will rest content until it has eradicated capitalism and put into operation the full programme of socialized planning which will lead to the establishment in Canada of the Cooperative Commonwealth.” By the 1950s, CCF leader MJ Coldwell considered the Regina Manifesto and such rhetoric to be a “millstone around the party’s neck.” Unlike the British Labour Party leadership that tried unsuccessfully to moderate Clause IV, the CCF issued a much more moderate Winnipeg Declaration.

The NDP has periodically redefined itself ever since. There were notable new NDP statements and self-definitions in 1961, 1969, 1983 and 1995. Heading into last weekend’s convention, the existing preamble to the party’s constitution hardly carried the symbolic or emotional weight of Labour’s Clause IV or the CCF’s Regina Manifesto.

The Social Democratic Legacy

By the time the CCF was transformed into the NDP in 1961, the party had clearly come to accept the broad parameters of a capitalist economy, but with an activist Keynesian fiscal policy, some elements of public ownership in a mixed economy, an institutionalized collective bargaining regime that facilitated the growth of moderate trade unions, and strong support for social programs such as public healthcare, pensions, unemployment insurance and social assistance.

In other words, the NDP from its beginning, under the federal leadership of Tommy Douglas (1961-1971), was a social democratic party. Just to be clear, I’m not using the term social democracy in some sectarian sense as an epithet. Hell, in this political climate, social democracy sounds pretty good, even radical. Historically, when the CCF-NDP said they wanted to reform capitalism, they meant it. But it has to be acknowledged that this social democratic agenda was never anti-capitalist or socialist in the sense of building a society beyond capitalism.

What Does the NDP Stand For?

The real crux of the matter is that since the end of the postwar boom in the mid-1970s and the onset of the neoliberal capitalist offensive soon after there has been less and less room for social reforms within capitalism. Forces on the Left have been on the defensive trying to retain historic victories and existing social programs.

Where there have been important victories, such as the increasing recognition of queer rights, these have been under the rubric of expanded liberal freedom and individualism within capitalism, rather than against capitalism. Struggles for equality within capitalism must continue to be waged and they demonstrate that some reforms and victories are possible. These issues remain quite central to the NDP even if there have been significant bumps in the past.

In this contemporary context, it actually would have been much more useful for the NDP to be seriously debating “social democracy” rather than “socialism” at its 2013 policy convention. Again, I don’t say that to be glib. What political and fiscal room is there for reforms under contemporary capitalism? How exactly, in an era of neoliberal dominance and an ongoing global economic crisis, do New Democrats propose to achieve, in the words of the new preamble, “a country of greater equality, justice, and … sustainable prosperity?” The answers to these questions are far from clear and the NDP hasn’t even attempted to seriously address them. The reality is that under Mulcair the NDP has continued to drift to the right.

The Decline of Socialism Inside and Outside the NDP

Perhaps the real story of the NDP’s new preamble is that it was passed so easily with relatively little mobilization against it. The opposition was weak. The Socialist Caucus and Fightback are tiny groups within the NDP and were unable to mobilize wider opposition to the changes. There are other socialists within the NDP but they are unorganized and, at this convention, seemed fewer in number than in the past.

Historically, left-wing challenges within the party – such as the Waffle Manifesto in 1969, the New Politics Initiative in 2001 and the leadership campaigns of Jim Laxer, Rosemary Brown and Svend Robinson – were able to generate support from 35 per cent or more of the delegates. The much smaller opposition to these changes to the party’s constitution, comprising just over 16 per cent of the delegates, is significant.

Clearly, many members of the NDP and delegates to convention felt defensive about the language of the preamble and feared partisan and media attacks about ‘socialism.’ There is a clear recognition that the NDP stands a chance to win the next federal election and the membership, as a whole, is willing to modernize the party’s language in order to maximize the party’s electoral chances.

Realistically, some socialists in and around the NDP will be less likely to volunteer for or even vote for the NDP in the next federal election. That said, the greatest mobilizing force for New Democrats will continue to be Stephen Harper and his Conservative government.

It’s probably safe to say that the new preamble to the NDP’s constitution is a more accurate and honest description of the party’s ideology and approach to politics than the old one.

Let’s be honest too. Amid the wreckage of neoliberal globalization and the economic crisis, it’s not as if there are thriving or growing socialist organizations outside of the NDP either. That is the larger and more daunting political reality that we face. •

In 2001, Murray Cooke was a delegate to the federal NDP convention, thanks to the Socialist Caucus, and voted for the New Politics Initiative resolution. This article was first published on the New Socialist website.