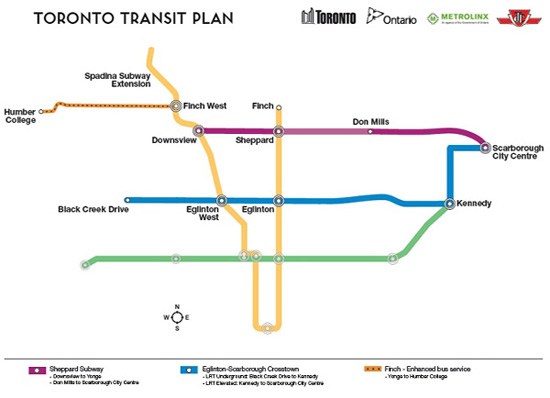

It seemed all our transit woes in Toronto were finally behind us. Mayor Rob Ford’s cancellation of Transit City had galvanized the mushy middle. In February, Toronto Council ignored his call for subways to vote in favour of four Light Rapid Transit lines (LRTs). At long last, the residents of Malvern and Jane and Finch in Toronto’s northern suburbs were going to get some much needed public transit. In retrospect this was only the lull before the storm. No one suspected that it signified the end of locally controlled, maintained and operated public transit. Two months later, the Ontario provincial government made the announcement that Metrolinx, a provincial arms-length agency meant to coordinate regional planning, was taking over for the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) Expansion Department. Construction of $8.4-billion worth of LRTs was being pushed back to 2014. They needed the extra time to pursue Alternate Funding Procurement (AFP) otherwise known as a public-private partnership (P3).

The TTC Expansion Department had already begun to oversee work on one of the Eglinton Crosstown LRT in 2011. However, a municipal transit authority with 50 years experience was going to be replaced by the province’s regional transit agency and a yet to be determined, multinational consortium. Metrolinx added the formality of a “positive value for money assessment” as if to claim an objective analysis would be carried out to compare private and public procurement. But in reality, the die had been cast. TTC staff was forced to clear out of their Eglinton office in July and Metrolinx staff moved in. Toronto’s new transit was going to be delivered through a crown agency with no experience in large transit infrastructure projects and no protocol for public consultation.

The TTC Expansion Department had already begun to oversee work on one of the Eglinton Crosstown LRT in 2011. However, a municipal transit authority with 50 years experience was going to be replaced by the province’s regional transit agency and a yet to be determined, multinational consortium. Metrolinx added the formality of a “positive value for money assessment” as if to claim an objective analysis would be carried out to compare private and public procurement. But in reality, the die had been cast. TTC staff was forced to clear out of their Eglinton office in July and Metrolinx staff moved in. Toronto’s new transit was going to be delivered through a crown agency with no experience in large transit infrastructure projects and no protocol for public consultation.

Set up to replace the Greater Toronto Transportation Authority by the Dalton McGuinty government in 2006, Metrolinx had already earned a reputation for being secretive. With a board of directors stacked with bankers, real estate company executives, a hotelier and various other business types, they were accustomed to closed door meetings, and relegating the public to a scripted agenda with no opportunity to depute. Another crown agency, Infrastructure Ontario, would be responsible for the ‘value for money assessment.’ They continue to use this skewed cost estimate despite an obvious bias toward privatization. The public cannot even verify the accuracy of their numbers. The P3s corporate confidentiality always trumps citizen’s right to know.

Privatization Trumps Public Transit Debate

Now that Metrolinx was conducting negotiations with the province of Ontario, City Councillors would need to sign a Master Agreement to hand over control of city right of ways, property and scope design (number of stations, length of transit line etc.). This would have been the only opportunity for the public to weigh in on privatization. But the fact that they were going to have to foot the bill didn’t matter. Council members, anxious to secure the funding for LRTs, refused to facilitate any kind of real and meaningful consultation with constituents. Nor would they discuss the findings of the American Public Transit Association report commissioned by TTC staff. The report concluded that such a huge ($8.4-billion) project would create less competition, not more and could result in “loss of public control.”

In September, Metrolinx let the other shoe drop. Operation of new LRTs would also be privatized. Although they later agreed to return responsibility to the TTC, this back room deal, brokered by the centre-left Councillor Joe Mihevc, was just a temporary fix. In ten years Metrolinx could negotiate a new contract with the private sector. There wasn’t much in it for TTC workers either. Most of the good jobs are in the maintenance of public transit, not in operations.

But as far as pro-LRT members of Council and their media allies were concerned, privatization was no longer the issue. Besides, the Province had threatened to withdraw funding if they didn’t go along with AFP. Even the Public Transit Coalition, an organization set up expressly to warn voters about the pitfalls of privatization during the 2010 municipal election was strangely quiescent. On November 1st, Council voted 31 to 10 in favour of the Master Agreement. According to TTC Commission Chair Karen Stintz, attempts to defer approval or ensure veto power over scope design, were met with similar threats to renege on funding, from Minister of Transportation, Bob Chiarelli. Provincial bullying had worked like a charm.

With Council more than willing to play the victim, given their timidity and lack of direction since the Ford election, it’s not hard to see how the public interest got lost in all the political arm twisting. But Toronto is not some small town in the middle of nowhere. Toronto is two and a half million people who generate billions of dollars in revenue for the Province. How do our municipal representatives justify their willingness to roll over and play dead? Especially when dealing with a leaderless, scandal ridden, minority provincial government. They obviously felt no obligation to defend the TTC’s jurisdiction over one of the largest public transit systems in North America.

Increased Costs with P3s

We could have another provincial election in the spring. If we end up with a Conservative or NDP government at Queen’s Park, what guarantee do we have that this agreement will survive? Many of us are old enough to remember when Mike Harris filled in the hole for the Eglinton subway in 1995. Tim Hudak is threatening to divert the money toward subways. If he wins, Mayor Rob Ford may still get his wish. Either way, there has to be a huge public outcry or trade agreements like NAFTA and the soon to be ratified Canada Europe Trade Agreement (CETA) will ensure P3s with foreign consortia continue to funnel profits out of our local communities and into offshore tax havens. Recent research on P3s in Ontario, conducted by Matti Siemiatycki and Naeem Farooqi of the Geography and Planning Department at the University of Toronto, conclude they cost 16 per cent more than regular government infrastructure projects.

The Canada Line in Vancouver is touted as a shining example of privately designed, built, financed, maintained and operated mass transit. However, closer examination reveals rising costs of almost $500-million. There are fewer station stops than originally planned and the public is on the hook for any shortfall ($21-million) in ridership targets. The Federation of Canadian Municipalities is against P3s. They want increased, long-term funding to be independent of privatization.

Ridership on the TTC is increasing each year with a projected 528 million in 2013. This trend continues despite the fact that transit users bear the financial burden of provincial underfunding through fare hikes and service cuts. Soon they will be forced to subsidize the private sector’s bottom line as well.

Where do we find people in Toronto with the courage to make similar demands on higher levels of government? It will certainly not be from among members of Toronto City Council. The concocted spectre of “no LRTs without P3s” was good enough for them to abandon their responsibility for local control and public accountability.

But this will just put more pressure on the people living in Malvern and Jane and Finch – neighbourhoods where good working-class jobs are scarce and poverty levels keep rising. Privatization of our public transit system will only exacerbate the hardship and inequality that has already taken up residence in Toronto’s outer areas. •