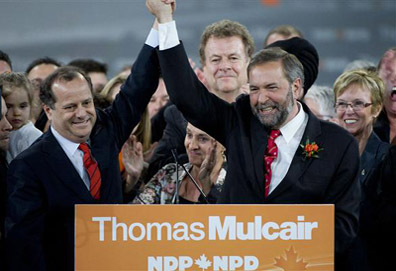

Mulcair’s Victory: What Does It Mean?

On March 24, the membership of the Federal New Democratic Party (NDP) elected Thomas Mulcair to succeed the late Jack Layton as their national leader, who tragically died of cancer in August 2011. With about 65,000 of the party’s 130,000 members participating in the leadership election, Mulcair prevailed over runner-up Brian Topp on the fourth ballot, receiving 57 per cent of votes cast. Mulcair, who was widely expected to prevail, takes over the NDP that had surged to Official Opposition in the Canadian Parliament in the ‘orange wave’ in the May 2011 election under the popular and charismatic Layton. For the first time in the party’s history, the forming of an NDP government is within the realm of possibility.

Layton’s Most Important Recruit

Layton, a native of Quebec, had made winning seats in Quebec a priority under his leadership. In 2007, Layton recruited Mulcair to run for the NDP and appointed him as the party’s Quebec Lieutenant; Mulcair had given a speech at the party’s convention in Quebec City the previous year. Mulcair was a popular Quebec Cabinet minister in the Liberal government of Jean Charest. In June 2006, Mulcair was removed from his position as Minister of Sustainable Development, Environment and Parks due to his opposition to the selloff of lands to private condominium developers. Mulcair was elected in a by-election in September 2007 in the longtime ‘safe’ Liberal riding of Outremont in Montreal; he was re-elected in the 2008 federal election, the first New Democrat to win a seat in Quebec in a general election. Upon entering Parliament, Layton appointed Mulcair as one of the party’s Deputy Leaders, along with left-wing Vancouver MP Libby Davies.

Layton, a native of Quebec, had made winning seats in Quebec a priority under his leadership. In 2007, Layton recruited Mulcair to run for the NDP and appointed him as the party’s Quebec Lieutenant; Mulcair had given a speech at the party’s convention in Quebec City the previous year. Mulcair was a popular Quebec Cabinet minister in the Liberal government of Jean Charest. In June 2006, Mulcair was removed from his position as Minister of Sustainable Development, Environment and Parks due to his opposition to the selloff of lands to private condominium developers. Mulcair was elected in a by-election in September 2007 in the longtime ‘safe’ Liberal riding of Outremont in Montreal; he was re-elected in the 2008 federal election, the first New Democrat to win a seat in Quebec in a general election. Upon entering Parliament, Layton appointed Mulcair as one of the party’s Deputy Leaders, along with left-wing Vancouver MP Libby Davies.

In the 2011 election, the NDP had a historic breakthrough in Quebec, winning 59 of its 75 seats and reducing the Bloc Québécois (BQ), which had held most of the seats in Quebec since 1993, to just four seats; even BQ leader Gilles Duceppe went down to defeat. Layton targeted Bloc supporters by appealing to a common social democratic outlook as well to an ‘asymmetrical federalism’ that would respect Quebec’s place in Canada; by uniting with progressives in English Canada behind the NDP, it was argued, the Conservative government of Stephen Harper, extremely unpopular in Quebec, could be defeated. Mulcair campaigned for the NDP throughout Quebec and was widely credited for playing a key role in the ‘orange wave.’

Having won 103 seats (of 308) in Parliament and over 30 per cent of the popular vote, the NDP became the Official Opposition, not only wiping out the Bloc in Quebec, but achieving their longtime goal of leapfrogging over the Liberal Party and replacing them as the main party of the centre-left; the Liberals under the disastrous leadership of Michael Ignatieff were reduced to just 34 seats. Although the Conservatives only won 5 seats in Quebec, they won overwhelmingly in English Canada and obtained a majority government. It was indeed a bittersweet result for many Canadian progressives. And with the death of Layton, whether the party’s gains in Quebec could be sustained remained very much in question.

The Leadership Contest

The leadership race officially began on September 15, 2011, with the convention to be held in Toronto on March 23-24, 2012. It was based on a One Member One Vote system of voting; the 25 per cent vote delegated to affiliated trade unions had been removed by the party’s federal executive. About 80 per cent of members who participated cast their votes in advance online or by mail based on a ranked ballot; the rest were cast ‘live’ by convention delegates and voters online. The party executive agreed to have a longer leadership race in order to allow leadership candidates to sign up new members in Quebec, where membership numbers were low and no provincial branch exists.

There were seven candidates in the race, including Mulcair, key party strategist Brian Topp, MPs Peggy Nash (Parkdale-High Park, ON), Nathan Cullen (Skeena-Bulkley Valley, BC), Paul Dewar (Ottawa Centre, ON) and Niki Ashton (Churchill, MB), and Nova Scotia pharmacist and businessman Martin Singh. Two other MPs who were elected in 2011, respected First Nations leader Romeo Saganash (Abiti-Baie-James-Nunavik-Eeyou, QC) and former Nova Scotia NDP leader Robert Chisholm (Dartmouth-Cole Harbour, NS), withdrew from the race.

Brian Topp was the first to declare his candidacy. Topp was a key figure under Layton, serving as national campaign director in the 2006 and 2008 elections, senior adviser to Layton in the 2011 election, and among the negotiators of the attempted Liberal-NDP coalition in the fall of 2008; he was elected president of the party in June 2011. He had previously served as deputy chief of staff to the government of Roy Romanow in Saskatchewan in the 1990s. Topp had the support of much of the party establishment, most notably from former leader and elder statesman Ed Broadbent, but also received an endorsement from left-wing icon Libby Davies. In spite of his role in the ‘modernization’ of the federal NDP as well as with the ‘Third Way’ Romanow government, Topp repackaged himself as a defender of traditional social democracy. Most notably, Topp came out in support of raising taxes on wealthy Canadians and corporations, even though under Layton the party had largely embraced anti-tax populism. For many, this ‘left turn’ came across as insincere and opportunistic. Topp also came under heavy criticism for never having been elected to office.

Mulcair, in contrast, pursued more centrist themes in his campaign. Mulcair cited the Third Way government of Gary Doer in Manitoba as the model he wished to emulate. He repeatedly criticized the NDP for ‘outdated’ language and told the Globe and Mail unlike other candidates (particularly Topp), he would not be ‘beholden’ to unions. In an interview with the Globe and Mail, Mr. Mulcair recounted how he informed the Canadian national director of the Steelworkers, Ken Neumann, that he opposed a reserved voting block for unions at the NDP leadership convention in March:

“It was quite clear he wasn’t used to being told ‘no’ by anyone in the NDP. And I said ‘no.’ I said, ‘Why not let the membership decide?’ Mr. Mulcair said of the ‘cordial’ conversation that occurred last month.”

And speaking in the language of Third Way ‘modernizers,’ Mulcair stated in an interview with the Toronto Star:

“We have to renew. We’re one of the only social democratic parties to never have renewed itself. One of the things that we did in Quebec was that we reached out beyond our traditional base. We identified ourselves as progressives but we didn’t stick with some of the 1950s boilerplate.”

Mulcair had the backing of 43 MPs, including the vast majority of Quebec MPs, as well as Premier Darrell Dexter of Nova Scotia and former British Columbia premier Mike Harcourt. Both Chisholm and Saganash endorsed Mulcair. With Mulcair’s much higher recognition and polling numbers in Quebec, there was a strong belief among many party members that Mulcair was the only leader who could hold onto their Quebec seats.

Another ‘modernizer’ was Nathan Cullen, whose central campaign plank was to pursue tactical cooperation with the Liberals in order to beat Harper. Under this proposal, members of the riding associations of “progressive federalist parties” – NDP, Liberal and Green – could vote to have a joint candidate in that riding, which would be chosen in a “progressive primary.” Although this proposal was opposed by the other leadership candidates, the charismatic Cullen was able to make his proposal a central topic of discussion in all-candidates’ debates. Cullen had a particularly strong following among young voters and was very successful in organizing on the Internet, with the online advocacy groups Avaaz and Leadnow.ca supporting his campaign.

Peggy Nash, a former negotiator with the Canadian Autoworkers (CAW) prior to her entry into politics and who later had a stint as party president, pursued more traditional social democratic themes in her campaign. Nash proudly spoke of her trade union background and the crucial role of the labour movement in terms of creating a more egalitarian society, and stressed the need to engage with social movements and to reach out to the disaffected 40 per cent of the population that no longer votes. Nash made proportional representation a key issue in her campaign. She had also had a strong following among the young, with the majority of her campaign workers being under 30. Nash was supported by former federal party leader Alexa McDonough, Left political economists Mel Watkins and Jim Stanford, and many prominent trade union leaders such as Ontario Federation of Labour president Sid Ryan, CAW president Ken Lewenza, and CUPE president Paul Moist.

With regard to the other candidates: Paul Dewar, who was backed by respected MP and NDP Ethics Critics Charlie Angus, saw his chances evaporate when his inability to speak French became increasingly well known; Martin Singh ran on an explicitly pro-business platform and served as a stalking horse for Mulcair; and Niki Ashton (at age 29 the youngest candidate), focused on traditional social democratic themes with a particular emphasis on generational inequality.

Anybody But Mulcair?

In the last few weeks of the campaign, ‘anybody but Mulcair’ sentiment increasingly solidified behind Topp, who repeatedly stated that “we don’t have to become Liberals to win” and warned that Mulcair would remodel the party on ‘New Labour’ lines. In an interview with Maclean’s, Topp stated:

“I think we’re having a debate about two views of the party. Mine is that the orthodoxy thinking that we have seen in Canada in the last 20 years or so has come from Liberals and Tories, who think that if you’ve got billions of dollars lying around in the federal government the best thing to do with them is to give them to rich people through tax cuts and that it makes sense to leave climate change to our children as an issue to deal with and that rising inequality is okay. That’s orthodox thinking in my mind. And new thinking comes from New Democrats who don’t agree with those priorities and propose alternatives. You can get back to a progressive tax system. You can deal with climate change now. You can work on equality now. An alternative view of the party, which I think Tom Mulcair essentially outlined when he launched his campaign, is that that’s wrong. That one of the problems that needs to be fixed in Canada is with our party. That our party needs to be reformed. And that what he has in mind in reforming the party is a reformation of the party somewhat along the lines of what Tony Blair did to the Labour party in the 1990s, which is an attempt to move the party more to the centre, to adopt an agenda that looks more like the agendas that have been pursued by Liberals and Conservatives because, in this argument, it’s the price of victory, the price of power…. Those are the two visions of the party that are before us.”

And in the last week of the campaign, Ed Broadbent came out swinging against Mulcair, expressing concern about his commitment to social democratic principles:

“Tom has talked about ‘boiler-plate’ social-democracy. What does he mean by that? Is he saying that concern about equality is a boiler-plate item? It’s not, it’s a core value.”

And What Were The Differences Exactly?

The discussion of policy details in this race was rather thin, with the candidates mainly distinguishing themselves in terms of articulation and the social bases they sought to mobilize rather than concrete policy differences. Topp’s taxation proposal, while hardly bold, represented a step in the right direction and a break from the anti-tax populism embraced by the NDP in recent years (ironically most likely under his influence as a party strategist!). Nash articulated a more ‘social corporatist’ approach to economic policy that is advocated by much of the social democratic policy community in Canada. And perhaps most interestingly, Ashton called for the creation of a new Crown Corporation that produced generic pharmaceuticals.

To the extent there were policy differences, Mulcair’s positioning was on the right. While opposing corporate tax cuts, he was reluctant to discuss personal tax increases, and his proposed cap-and-trade program would finance general revenues. Although the party had largely deemphasized the issue of free trade in recent years (though Ashton and Nash took more critical positions in their campaigns), Mulcair broke from party orthodoxy and openly embraced free trade. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) has been heavily criticized for its harmful impact on the environment and workers’ rights, yet Mulcair stated he supports NAFTA and even helped draft some of its provisions on professional services. Mulcair’s stance on Israel/Palestine also came under fire from Palestinian solidarity activists, in which his position was closer to that of the extremely pro-Israel Harper government than it was to that of the other leadership candidates.1

On the first ballot, a majority of votes (52.6%) went to ‘modernizers’: Mulcair (30.3%), Cullen (16.4%) and Singh (5.9%), 28.9% went to ‘status quo’ candidates Topp (21.4%) and Dewar (7.5%) and just 18.5% went to ‘Left’ candidates Nash (12.8%) and Ashton (5.7%). Ashton was eliminated and Singh and Dewar dropped out after the first ballot; Nash was eliminated on the second ballot. Yet there was little evidence of a strong left/right polarization among the party membership. About one-third of supporters of the ‘left-wing’ Nash, for instance, went to the ‘right-wing’ Mulcair. And many long-time Left figures in the party, such as Gerald Caplan, James Laxer and Steve Langdon, backed Mulcair. Ideological differences were apparently so negligible that it made sense behind the ‘winner’; Topp’s heavy-handed tactics and anti-‘establishment’ sentiment likely also pushed voters toward Mulcair.

On the first ballot, a majority of votes (52.6%) went to ‘modernizers’: Mulcair (30.3%), Cullen (16.4%) and Singh (5.9%), 28.9% went to ‘status quo’ candidates Topp (21.4%) and Dewar (7.5%) and just 18.5% went to ‘Left’ candidates Nash (12.8%) and Ashton (5.7%). Ashton was eliminated and Singh and Dewar dropped out after the first ballot; Nash was eliminated on the second ballot. Yet there was little evidence of a strong left/right polarization among the party membership. About one-third of supporters of the ‘left-wing’ Nash, for instance, went to the ‘right-wing’ Mulcair. And many long-time Left figures in the party, such as Gerald Caplan, James Laxer and Steve Langdon, backed Mulcair. Ideological differences were apparently so negligible that it made sense behind the ‘winner’; Topp’s heavy-handed tactics and anti-‘establishment’ sentiment likely also pushed voters toward Mulcair.

Unions, too, were all over the place in terms of support. Nash had significant labour support, notably from provincial labour councils and from the CAW and CUPE. Topp was supported by the United Steelworkers (USW) as well as the Communication, Energy and Paperworkers Union (CEP). And in spite of Mulcair’s statement of not being ‘beholden’ to unions, Mulcair received the endorsements of the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) – Canada’s largest private sector union – and the Service Employees International Union (SEIU).

A Break or Continuation?

A majority of those who cast ballots in the NDP leadership contest backed a candidate who ran against the legacy of the party to the extent it exists and pursued a more transparent Third Way campaign. But does this represent a fundamental shift in terms of party ideology and organization, or does it merely represent a continuation of the ‘modernization’ process that accelerated under Layton and the trajectory of social democracy since the 1990s in accommodating neoliberalism?

Opponents criticized Mulcair for stating that the party had not ‘modernized,’ on the grounds that the party indeed ‘modernized’ under Layton, without compromising ideology. There was no recognition that a move to the centre had occurred under Layton.

Yet, as Murray Cooke observed:

“Layton was able to moderate, simplify and carefully package the NDP message. He simply ditched many controversial policies. During the 2004 election, he single-handedly dismissed the NDP’s longstanding support for pulling Canada out of NATO. With each campaign, Layton would focus on a small number of modest reforms. Increasingly, the NDP would speak for ‘middle-class’ Canadians. By the 2011 election, the NDP was proposing to reduce the small business tax to reward ‘job creators.’ Certainly, the 2011 platform was a more moderate program than anything ever offered under any previous federal NDP leader. It became harder and harder for the mass media to depict the NDP as the socialist hordes.”

It is ironic indeed that the NDP establishment was defeated in this race – from the right. Yet the repackaging of the NDP as a modern, progressive party of the centre-left likely means that ideology of the membership has changed in recent years. Murray Dobbin raises two possible reasons as to why Mulcair prevailed. One possibility is that party members

“…like increasing numbers of Canadians in general, simply don’t read as much and that information about Mulcair did not get through to them. To what extent did NDPers devote time and energy to finding out about the candidates? In general, what is the state of member education and engagement in the party?”

A second, and more concerning possibility is that

“NDP members had indeed heard the negative aspects of Mulcair’s politics and voted for him anyway. That’s a very different problem. It reflects what I have observed about the NDP for decades now: its decreasing emphasis on policy and philosophy and the increased – political machine driven – preoccupation with winning seats in elections, often out of context of the political moment and oblivious to unintended consequences. One prominent NDPer I spoke to responded to my shock that he was supporting Mulcair with a sort of football game enthusiasm. ‘I think he can take on the bastard [Harper].’

“Facing a ruthless tough guy? Get your own ruthless tough guy. And possibly create a monster you can’t control. It is as if policy, philosophy, and vision for the country have simply been devalued to the point where they are an afterthought or some vaguely interesting historical relic. There seems to have been a kind of ‘We’ll worry about policies later, let’s pick someone who can win first.’”

As a ‘government-in-waiting’ and with Mulcair at the helm, the path of moderation will likely continue to accelerate. Indeed, Mulcair received especially favourable media coverage and as Derrick O’Keefe revealed, campaign contributions from several figures in the upper echelons of the Canadian capitalist class. These contributors included Gerald Schwartz, the billionaire CEO of Onex and four of the nine members of the Onex board of directors, Anthony Munk of Barrick Gold and Onex, Mitchell Goldhar, the billionaire CEO of SmartCentres and John Sherrington, Vice Chairman of Scotia Capital.

Is the NDP preparing to compete with the Conservatives as a ‘party of business,’ as was the case of Tony Blair’s ‘New Labour’ in Britain? It is apparent that the NDP has ‘arrived.’ In response to Mulcair’s victory, John Ibbitson, Ottawa Bureau Chief of the Globe and Mail, the voice of the Canadian establishment, stated:

“Mr. Mulcair earned a clear mandate to move the party in a new direction, one that acknowledges the challenges facing, not just workers, but business and government itself; that espouses a principled foreign policy while stripping away the pollyanna pacifism of the NDP’s traditional stands; that seeks to improve the environment without disemboweling the economy.

“Call it the New New Democrats, since it was the brand New Labour that worked in Great Britain for Tony Blair.”

And the Globe editorial board praised the election of Mulcair as a triumph for “pragmatism” and encouraged Mulcair to follow through on the path of moderation:

“He will need to move cautiously in order to avoid a splinter on the party’s left, but he must not be stymied by it. The greater risk would be to not do enough to dispel the notion that the New Democrats are a party of the left, one beholden to organized labour, and that Mr. Mulcair is as the Tories would have him, a leftist outside the political mainstream.”

Yet the NDP is unlikely to outdo the Conservatives as the party of business. The economic strategy of the Harper government, of making Canada an ‘energy superpower’ by the development of the Alberta tar sands, is backed by the Canadian capitalist class. Mulcair’s ‘go slow’ approach to tar sands development, wherein the environmental costs would be internalized in order to offset the so-called ‘Dutch disease’ that has driven up the Canadian dollar at the expense of Canadian manufacturing, runs against a key alliance of Canadian capital.2

Canadians are likely to turn against the hard-right Harper Conservatives in the next federal election in 2015, and with the Liberal Party likely on its deathbed, Mulcair is well positioned to become the country’s first NDP Prime Minister. The historical legacy of the party will be diluted further as the party more and more resembles New Labour or the U.S. Democratic Party. Mulcair’s strategy to form government appears to be to squeezing down what remains of the Liberal vote further and appeal to disaffected Conservatives, while taking the traditional social democratic constituency for granted. An anti-Harper strategy is not synonymous with an anti-neoliberal strategy, however, as the NDP, like social democracy in general, has no clear anti-neoliberal strategy in practice. Left to its own devices, the NDP will continue to move further to the political centre. The question for unions and social movements is how can they open up space for a more clearly anti-neoliberal politics, should the Mulcair-led NDP disrupt the hegemony of Harper over the Canadian political scene. •

Endnotes

- Mulcair has pressured the NDP to move in a more pro-Israel direction. In 2008 he led a caucus revolt after Layton criticized the Harper government’s decision not to participate in the United Nations Conference on Racism and pressured the NDP to mute criticisms of Israel’s attack on Gaza in January 2009. In 2010, Mulcair publicly criticized fellow Deputy Leader Libby Davies for stating to a reporter that the occupation of Palestine began in 1948 and joined Harper and then-Liberal Foreign Affairs Critic Bob Rae in calling for her resignation. Unlike the other leadership candidates, he refused to come out in support of the Palestinian statehood bid at the United Nations.

See Sid Shniad and Fabienne Presentey, “Thomas Mulcair: Israel Right or Wrong,” November 30, 2011 and Canadians for Justice and Peace in the Middle East, “Thomas Mulcair unaligned with NDP policy on the Middle East,” February 15, 2012. - John Ivison, “When NDP leader runs into Western public opinion there will be blood,” National Post, March 25, 2012.