Drumming Up a Healthcare Crisis

The Drummond Report’s Implications for Health Policy

In a Maclean’s interview in November 2008, former TD Bank Chief Economist (2000-2010) and head of the eponymously titled ‘Drummond Report’ spoke truer than he might have then known. Don Drummond, who spent 23 years in the Federal Ministry of Finance, was asked if he missed “being in the middle of the action,” to which he replied:

“There’s definitely a buzz from being there when the economy is turbulent, and I would be surprised if there weren’t people in the government who didn’t take some perverse…pleasure’s the wrong word, but interest in what’s going on. You don’t wish for anybody to lose their jobs or investments, but it is fascinating and there is an adrenalin rush; it taxes your analytical skills and your knowledge of history, looking back to see if there are parallels. It’s great when everything’s going smoothly, but more exciting when it’s not” (author’s emphasis).

Where to start? Drummond makes it clear that whether on Parliament Hill or Queen’s Park, reputations are made or broken in a crisis. His name became equivalent with fiscal pragmatism after he helped Prime Minister Paul Martin return the federal government to an operating surplus in the late 1990s. Able to enjoy the feral experience of the Ministry of Finance during a crisis, Drummond’s composure made him one of the most decorated public servants, the type for whom privatization is his most public utterance.

The Right Man for the Job

So it is of little wonder why Ontario’s Premier Dalton McGuinty would pluck Drummond from his retirement in 2010 to head the “Commission on the Reform of Ontario’s Public Services.” The report, a two-volume, 500-odd paged tome containing 362 recommendations, gives us the “hard answers and difficult solutions” (p. 15) to put the public services for Ontarians back on the “path to sustainability and excellence.”

The essence of the Drummond report is that he presents “hard answers” to fallacious problems. Conditioned by the bankerly orthodoxy of the Ministry of Finance, Drummond rehashes every troupe and pretext from the Mike Harris years. The old gruel is served lukewarm:

“To meet its own goal of a balanced budget in seven years, the government will have to cut program spending more deeply on a real per capita basis, and over a much longer period of time, than the Harris government did in the 1990s” (p. 10).

Before we are able to discuss Harris-style cuts, then and now, we ought to examine critically the theory and practice of this Commission. We can then turn to the real problems pestering the public healthcare system in Ontario.

Consultancy Politics

Drummond’s enthusiasm for the Harris years is grounded in not just what Harris did, but how he did it. In a study of the Canadian economy during the 1990s, he claims that what the federal and provincial governments did, it was both more successful than the ruling class foresaw and less painful than the underclasses claim it was.

“However, at the very worst, the charge against deficit elimination is that there was some short-term pain to secure substantial long-term gain”1

Patience is a virtue, Drummond told those who were downsized, and yet when the long-term gains never materialized for Ontarians, Drummond replied we need a second round of cuts before we all reap the refinements. Consider the following statement in light of the one above:

“The government must set out a 20-year plan with a vision that all Ontarians can understand and accept as both necessary and desirable – a plan that will, though it involves tough decisions in the short term, deliver a superior healthcare system down the road” (p. 15, author’s emphasis).

Taking his own work as inspiration, Drummond has no quarrel about quoting himself, over a decade later, or refashioning his earlier turn of phrase to absolve himself of the false conclusions he drew from the 1990s. The short-term cuts produced no perceivable “long-term gain” for Ontarians according to the numbers in the 2012 Drummond Report. Are we now to trust that “tough decisions in the short term” will produce “a superior healthcare system down the road”? How is this demagogy permitted?

The Drummond report, though, is but one expression of the larger question over the role of consultants in the new business of government, the outsourcing of debate and policy-making, and the recruitment of so-called consultancy experts to lend credibility to ‘tough answers.’

In Riding the Third Rail: The Story of Ontario’s Health Services Restructuring Commission, 1996-2000 (2006), the authors, themselves members of the Hospital Services Restructuring Commission (HSRC) throughout its four year existence, explain in flat tones the benefit to government of these commissions.

“The strategy of putting the commission at arm’s length, insulated from the influence of politicians, was an effective one, for the HSRC could make decisions that the government itself could not, at least not in a timely fashion” (2006: p. 231).

“Government’s currently feeble approach to governance…would be greatly enhanced by the use of arm’s-length bodies, a genuine devolution of responsibility and authority to organizations…such devolution would allow, even require, governments to concentrate more on governance/leadership – what is to be done and the results – and less on managerial issues – how it will be done, issues better handled by people on the ground” (2006: p. 232).

Perhaps more revealing than the HSRC CEO, Duncan Sinclair, intended to be, he makes clear the best governments are the ones that leave democracy and policy to the unelected experts and busy themselves with the task for tendering P3 contracts, without asking too many ‘how’ questions. The essence of consultants in neoliberalism is to lend ‘objectivity’ to public-private partnerships, which is to say, to continue the trend of subsidizing corporate profits by embarking on a PR campaign that presents this as a wholly new but ‘tough’ answer.

The Substance of the Drummond Report:

Completing the Harris Revolution

For all the reverence Drummond piles on the Harris revolution, he is not content with being a mere reincarnation. While assimilating the ‘successful’ aspects of the Harris revolution, Drummond is quite conscious of the fact that Harris, after having succeeded on many fronts, was ultimately thwarted in the healthcare overhaul.

“After the 1995 election, the Harris government substantially reined in spending, with the exception of healthcare; the two most dramatic moves were a 22 per cent cut in social assistance rates and a downloading of program responsibilities to municipal government, with a partial fiscal offset from other changes in Ontario-municipal relations and the induced reductions in overall welfare expenditures” (p. 9).

Like Bill Clinton to Ronald Reagan, Tony Blair to Margaret Thatcher, Gerhard Schroeder to Helmut Kohl, liberals publicly proclaim the government as an ‘activist’ for the powerless but proceed in making the state into an ally for those already rich and safe. The essence of the Drummond report, indeed of the McGuinty government for which it is in the service of, is both reassurances for the rich and populism for the poor.

At the beginning of the Drummond Commission, he outlines his 5-part mandate:

1. Advise on how to balance the budget earlier than 2017-18.

2. Once the budget is balanced, ensure a sustainable fiscal environment.

3. Ensure that the government is getting value for money in all its activities.

4. Do not recommend privatization of healthcare or education.

5. Do not recommend tax increases (p. 11).

All but one of these mandates is followed-up by a single affirming sentence to uphold the mandate. When it comes to mandate 4 however we find: “We interpret this to mean that healthcare must be kept within the public payer model. We do not interpret it as denying opportunities for private-sector delivery of services, if that is more efficient.” Equivocation of this caliber helps explain Drummond’s popularity among Ontario’s upper crust.

It was mentioned earlier that Drummond’s “hard answers and difficult solutions” are only solutions to fallacious problems. And the following is a step-by-step explanation as to why this is so.

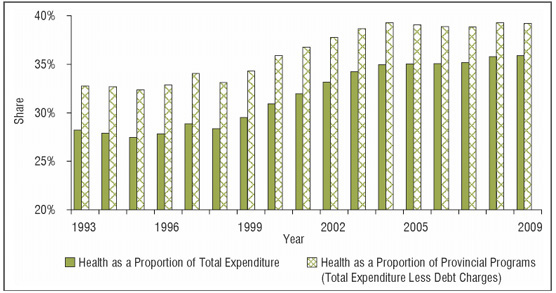

I. Healthcare is the Biggest Item in the Ontario Government’s Budget

This claim preys on fear and prima facie deception. Healthcare is the biggest portion of the Ontario government’s budget but it is not because of irretrievably spiraling costs nor imprudent sums of money being put into the budget envelope. Healthcare is the biggest item of the government’s budget because of the cuts made to other budget items.

But what is the basis of this estimate? Healthcare expenditures have been stable if not stagnant over the McGuinty era, with the bulk of increases coming under his Tory predecessors, which ended in 2003. This is according to Canada’s national authority on health indicators. Canadian Doctors for Medicare provide an important analysis of the same chart:

“Almost all of the growth in healthcare’s share of provincial budgets can be attributed to the simple arithmetic of an essentially constant numerator and a decreasing denominator. Deep cuts in federal transfers to the provinces in the mid-1990s were compounded by provincial tax cutting policies in the latter part of the decade, causing significant reduction in total provincial budgets” (p. 4).

Spending hasn’t been out of control, cutting has; and the true meaning of a government deficit, between what the wealthy really pay and what they ought to pay, is what should be debated if the McGuinty government hadn’t franchised democracy to TD economists.

But the stagnation in public healthcare spending isn’t the whole story – it is just what the government tenders. Costs are indeed going up, currently at $75.5-billion for total health expenditures (including insurance and user fees), 6th highest in the OECD.

II. “The healthcare system is costly,”

“the system isn’t as public as most people think”

These are treated as distinguishable problems in the Drummond report (p. 154) but when placed together as separate but dependent clauses of the same statement, the true essence of the problem is glaring.

Rising costs are bred in the bone of privatization and this is doubly clear in the long-term care and pharmacare sectors. It has never been sufficiently explained by those who favour privatization how the introduction of shareholders value and their marketing schemes will translate into savings and front-line care. Now it should become clear why the former CEO of the HSRC says the best governments don’t ask ‘how.’

The government-consultancy-business trichotomy is at work in the long-term care sector and provides an understanding the connection between privatization and squandered public money. Shelley Jamieson, the former chair of the Ontario Health Providers Alliance, was appointed to the HSRC, which recommended, in brief, hyper-privatization of services like long-term care.

In the midst of her tenure on the HSRC, she was made the CEO of Extendicare Care, the biggest U.S. multinational operating in Canada. Between Extendicare, Central Park Lodges, and Chartwell, 40 per cent of the 20,000 new long-term care beds announced by the Harris government went to these three companies.

From lobbyist to consultancy and into the CEO of a multinational trust fund, Jamieson completed the trifecta when McGuinty appointed her as Ontario’s Cabinet Secretary in 2007 (the most senior public service position in Ontario). She was previously deputy minister of transportation, where accountability is only to the Privy Council (meaning the premier and cabinet).

| Figure 2: Long-Term Care beds by province and ownership, 2008 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province | Non-profit beds | For-profit beds | Total beds | % Non-profit | % For-profit |

| BC | 17,028 | 7,588 | 24,616 | 69% | 31% |

| Alberta | 10,230 | 4,424 | 14,654 | 70% | 30% |

| Sask. | 8,273 | 671 | 8,944 | 92% | 8% |

| Manitoba | 7,280 | 2,553 | 9,833 | 74% | 26% |

| Ontario | 35,100 | 40,100 | 75,200 | 47% | 53% |

| Quebec | 35,638 | 10,453 | 46,091 | 77% | 23% |

| NB | 4,175 | 216 | 4,391 | 95% | 5% |

| NF | 2,747 | 0 | 2,747 | 100% | 0% |

| NS | 4,190 | 1,796 | 5,986 | 70% | 30% |

| PEI | 578 | 400 | 978 | 59% | 41% |

| Canada | 125,239 | 68,201 | 193,420 | 65% | 35% |

It is stating the obvious to say that Jamieson was responsible for implementation of privatization of long-term care in Ontario, one of the most rapidly growing healthcare markets in the country.

Ontario has become the largest market for long-term care and this has meant huge user fees for residents and huge profits for the shareholders, while contributing to the diminution of the quality of care found in these homes. Far from this being mere ideology, an insurmountably large amount of studies confirm a negative correlation between the proprietary status of long-term care homes and the quality of care found inside these assets – I mean homes.2

As CUPE researcher and Left Words blogger Doug Allan has demonstrated, user fees in Ontario long-term care homes are 10% higher than the Canadian average. And this figure has been steadily climbing as for-profit long-term care homes have been able to add beds that charge hire user fees.

| Figure 3: Private funding as a percentage of total LTC expenditure (2011) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homes for the Aged | Ontario | % of total | Canada | % of total |

| Total, income generated in operating residential care facilities | 4,855,498 | 13,700,780 | ||

| Co-insurance or self-pay | 1,472,995 | 30.3% | 3,018,147 | 21.9% |

| Differential for preferred accommodation | 148,171 | 3.1% | 205,316 | 1.5% |

| Total | 33.4% | 23.4% | ||

*Numbers in thousands (000s); Statistics Canada, Residential Care Facilities Survey, taken from Table 8-7, CANSIM table 107-5508.

The Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care subsidizes long-term care at a rate of roughly $154 per resident per day (per diem) with residents paying a sliding scale from $0 to $58 in user fees per diem. This money goes into 4 envelopes: nursing, services, food, and accommodations. Every long-term care bed receives this subsidy regardless of ownership structure. The stock in trade of corporate profiteering is to move as much costs into nursing, services, and food and while putting surplus money into the accommodation envelope. This last envelope is the only envelope where surplus money is rendered into profit, all other surplus from the envelopes is rebated to the government.

The true fiscal crisis afflicting long-term care is that the public sector is increasingly subsidizing corporate profits. Private long-term care facilities unduly shift costs (like incontinence supplies) into staffing envelopes and bolster profits taken from the accommodation envelope.

The rising costs of pharmaceuticals are no surprise to readers of The Bullet. In the U.S., pharmaceuticals give lobby money predominantly to President Obama and Mitt Romney, and they do it presumably without the intention of having their candidate create a single payer-model. In Canada, between 2003 and 2005 alone, premiums for private drug plans increased by 15 per cent. This is double the price increase of the drugs themselves.

As the Canadian Doctors for Medicare explain, as a proportion of total health spending, public sector drug plans cost 1.3%, private sector plans cost 13.2%. If ever there was a stat to make the case for a universal drug plan, this is surely it.

Alternatives to the Drummond Report

Drummond’s critics are the way we are not because of an aversion to the tough answers, only to the wrong ones. Ontario’s healthcare system suffers from opaqueness and mystery, especially in the sectors where the system has been captured (as in market share) by monopoly trusts.

Instead of the privatizations that Drummond calls for (Recommendations 3-5, 14-7, 15-7, 16-6, and 17-5 to name a few), there are three main sources of cost increases that the left has advised would provide sufficient savings in the long-term:

1. A universal and public drug plan to contain costs (see above);

2. Transparency in long-term care homes;

3. Enforcing the Employer Health Tax

Figure 4: EHT revenue and exemption cost

Source: “Closing the Employer Health Tax Loophole” in First Do No Harm: Putting Improved Access and Accountability at the Centre of Ontario’s Health Care Reform, Ontario Health Coalition, February 10, 2012, p. 49.

Somewhere in the law’s fine print is a loophole through which employers with huge payrolls are able render public money into non-taxable private wealth. The Ontario Health Coalition’s economist Hugh Mackenzie has calculated that closing this loophole would return $2.4-billion to the public purse.

Transparency moreover would mean the public is allowed to examine the books of the for-profit homes that our government tenders money to. Currently, the public is deemed unfit to know the deliberations in these boardrooms or the profit side of their ledgers. By legislating these homes to come under some form of public scrutiny, the public money going to unproductive labour can be retrieved.

Of all the time I have spent researching healthcare and covering the debate, the more I have realized one simple fact: the more eloquent and enticing the argument for privatized healthcare is, the more it should raise your suspicion. The claims made by the Ontario Health Coalition (OHC) are modest and well researched. They require no new levies or taxes and avoid the arid austerity of cut and slash politics. •

Endnotes

- Drummond, Don “Deficit Elimination, Economic Performance and Social Progress in Canada in the 1990s” Review of Economic Performance and Social Progress, Volume 1, p. 140.

- Harrington, Charlene et al “Quality of Care in Nursing Homes: An Analysis of Relationships among Profit, Quality, and Ownership” Medical Care, vol. 41. No. 12 (Dec. 2003), pp. 1318-1330; Comondore, Vikram et al “Quality of care in for-profit and not-for-profit nursing homes: systematic review and meta-analysis” BMJ (2009), 339:b2732-b2732.