Mayor Ford versus CUPE Locals 79 and 416: Some Thoughts on Strategy

As the Canadian government and its provincial equivalents take part in the global push for austerity, its after effects have significantly strained the fiscal and political dimensions of municipal governance. More than a year after right-wing populism swept through the City of Toronto, the agenda of the Rob Ford Administration has shown itself to be as administratively vacuous as economically delusional. Notwithstanding reality, however, public sector workers still continue to suffer from widespread resentment and political antipathy. This is why Ford and council, with the support of Toronto and Canada’s ruling classes, continues to be so forceful with respect to layoffs, service cuts, asset sell-offs and so on. Despite Rob Ford’s calamitous slide in popularity, significant reforms are threatening to fundamentally overhaul the delivery and quality of public services in the city.

In preparation for a major showdown with public sector workers in Toronto – one of the few remaining bastions of union strength and workplace precedent-setters in Canada – the City appears hell-bent on a 2012 lockout as CUPE Locals’ 79 and 416’s contracts expire at the end of 2011. Rob Ford has unmistakably revealed where the ‘fat’ now lies: “The gravy is in the number of employees we have at City Hall.” Having been unable to find any evidence of irresponsible spending, inefficient service delivery and unproductive workers, city employees and the users of its services are now enemy number one at City Hall. Since taking office Toronto’s public service has already been reduced by more than 2,300 workers, mostly from leaving vacancies unfilled, including the recent announcement of 1,200 layoffs, with plans to further reduce the city’s workforce by another 5000 positions over the duration of Rob Ford’s term.

Undermining Social Infrastructure

Ford has revealed in the year since his election that he’s ideologically fixated on “Selling the City,” and so despite the rhetoric of ‘efficiencies’ the cuts keep piling up. As budget consultations have heated up in the months preceding Council’s January 2012 final vote, it has been revealed that the City is sparing no effort to reduce services and delivery standards, layoff employees and undermine the social infrastructure of the city.

Ford has revealed in the year since his election that he’s ideologically fixated on “Selling the City,” and so despite the rhetoric of ‘efficiencies’ the cuts keep piling up. As budget consultations have heated up in the months preceding Council’s January 2012 final vote, it has been revealed that the City is sparing no effort to reduce services and delivery standards, layoff employees and undermine the social infrastructure of the city.

Recent plans for cuts include: plans to close three city-run daycares and seven community pools; sub-contract the private sector to build the Eglinton-Scarborough LRT (in part pushed by the Ontario Liberals’ “alternative financing and procurement” P3 agency[1]); contract-out snow ploughing, salting, street sweeping and road work (affecting 70 permanent positions and 170 seasonal positions); cut 12 after-school care and 58 student nutritional programs; eliminate no-charge recreational programs for underserviced children, youth and seniors at 22 priority centres; close 12 community centres and eliminate nearly 60 per cent of the city’s full-time youth outreach workers from 29 to 12 (affecting roughly 180 positions); slash sixty-two bus and streetcar routes, including raising fares by 10-cents, leading to longer wait-times and more densely crowded buses; dismantle two or three of the cities HIV/AIDS programs and three drug prevention centres; close three shelters, and contract-out an additional five more (affecting roughly 220 full-time equivalent positions); and raise property taxes by 2.5 per cent. All this, and more, is in the face of a $140-million year-end budget surplus for 2011; and if past underestimates are any indication, could top $200-million by years end!

As Locals 79/416 enter bargaining, reports suggest the City is seeking concessions in the realm of a 10 per cent cut in pay and benefits, the removal of job security provisions, reductions in hours of paid-work, modified duties and sick-time coverage, layoffs, privatization, contracting-out and the use of scab workers in the event of a lockout. As argued before, these contract negotiations will not only be the test of the Ford agenda and whether conservatives can consolidate their hold over Council, but reveal whether the Toronto and Canadian labour movement as a whole is up to the task of fighting back effectively.

This setting requires some exploratory thinking on a progressive labour strategy, in particular for CUPE Local 79 (and related to 416), given the harsh fact that the economic crisis has so far strengthened reactionary forces and efforts to reconstruct neoliberal policy frameworks. Such rethinking has broader implications for unions and community activists as a whole. The political failure of Local 79 and 416 to galvanize support throughout the 2009 civic workers strike, which was a failing of the broader labour and progressive community (and particularly revealing the political slide into neoliberal urbanism of the NDP councillors and the prior David Miller administration), needs to be kept in mind. The public backlash that followed led to the election of Rob Ford, and therefore discussions of a progressive strategy are ardently needed.

A Turning Point Struggle

for Canadian Public Sector Unions?

Two recent videos, the first “Toronto Emergency Warning,” and the second “CUPE National: Move Your War Room to Toronto Now,” warn of Canadian unions confronting a “PATCO moment” – a reference to the Airline Pilots’ union strike in the U.S. crushed by Ronald Reagan, setting in train the massive retreat of U.S. unions. The videos argue that Mayor Rob Ford has openly declared class war on Torontonians, and warning Canadian labour that CUPE Local 79/416’s fight is their fight is not enough; hence the need for CUPE to take a more active and interventionist role by moving their headquarters to Toronto.

While there will of course be meetings, promises of support and demonstrations, the question is what CUPE as a union is prepared to do. Will it in response consider disrupting the city in a way that puts pressure on Ford directly and also indirectly via the city elite? Will it be able to garner some modest public support in light of 2009’s backlash? With a general strike (at least at present) still off the agenda, these recent videos try to reveal where potential openings lie for workers and community activists. This may include, as the videos make note, a slowdown in one section one day, another a few days later, the removal of services for half a day somewhere else, sit-ins, a teach-in with clients a different day, and eventually, rolling days of action across the city. It must be recalled that we are speaking about a movement that has been stumbling along for so long and is still on the defensive even after a profound economic crisis that should have put it on the offensive. How can it possibly and suddenly act so decisively? The point is we need to take the risks while we still have some capacity to do so, or risk continuing along the several decade long union impasse and decline in general living standards.

While there is certainly good reason to be critical of CUPE National’s ability to coordinate the working-class as a whole, let alone in conjunction with Locals 79 and 416, the 2002 and 2009 strikes made it painfully clear that the Locals cannot go into this fight alone. Even with the support of community groups, social justice activists and other unions, the mobilizational capacities, resources and organization, including public support just wasn’t there. Furthermore, with CUPE National confined to the sidelines, the strike was almost entirely run by Local 79/416’s Executive Committees, while also resulting in an overwhelming majority of rank and file members being left out of the loop. A call for solidarity without substance is mere posturing. Transforming our unions internally and its relationship to others affected by the concerted push for austerity, means coming to terms with what we’re up against and the inadequacies of past bargaining strategies. In this vein, we’re all trying to figure out what is possible and necessary.

Local 79: Up to the Task?

With the recent (and unexpected) experiences of Wisconsin, the Arab Spring and the Occupy protests inspiring a wave of radical activism, it is crucial that CUPE Locals 79 (and 416) develop some broader strategies for fighting back. Of course, the related question here is how to ‘frame the message’ and strategize around it; in other words, the so-called ‘public relations’ war. First and foremost, the issues of bargaining and keeping the service public should be put at the forefront of the unions’ demands. Why can’t the bargaining message in this round simply be the following: ‘We have no collective bargaining demands. Our only concern is to keep the service in public hands and not hand it over to the 1 per cent. We just want to keep doing our work in a fair and equitable manner.’ Could this translate into a positive public reaction while laying the foundation for encouraging connections between public services and public workers? Might this reveal the multi-layered linkages with the users of those services and communities?

Let’s take the issue of garbage collection as one example. Past experiences have shown this to be a lightning-rod for public and media attention. While representative of a minority of workers on strike in previous years, it is without question the most visible and conflict-ridden source of frustration (not to mention the major source of leverage and point of attack for the union). Suppose the city follows through with a lockout and brings in private garbage collectors to scab (as we know the company has already been chosen under the table, perhaps illegally through a bidding process). In addition to exposing what happened in other similar cases – underbidding and then falling services and escalating costs – the union movement would be at war and need to stop the garbage trucks. This would require, for example, the capacity and organization of community pickets, car cavalcades blocking the trucks and so forth.

The message would be that ‘we’d like to pick up the garbage and like you we’re trying to hang on to our jobs; tell Ford to back down from his attempt to lower working-class standards and favour his 1 per cent friends and we’ll be back doing what we should be doing.’ No doubt people will be angry but perhaps this gives us a shot at channelling the anger against Ford in a way that we failed to do in 2009. In this context, maybe it is also possible to re-direct the right-wing media’s emphasis on ‘jobs for life’ away from resentment into other questions. For example, what is wrong with working people wanting to hang on to decent-paying jobs providing services we all need? And that Ford really wants to end job security so he can cut services: why else make such a fuss since population and garbage are growing, especially when the evidence shows that garbage privatization is no cheaper or more efficient but to the contrary?

Unfortunately, Local 79’s executive committee is still struggling to move beyond the limits of past strikes and to re-think the way union organization needs to adjust to the new climate. The turn in the Miller regime toward neoliberalism already demonstrated that the old clientalistic relations between union leaders and progressive city councillors is gone. They could do nothing to prevent the decline of the city, the consolidation of neoliberal urbanism and the needless decision by the City Executive to force a strike. Like the 2009 organizational failure of 79/416, with contracts set to expire in about one week the union has failed to thoroughly inform members of concessionary demands leaving many rank and file workers in the dark. How can union members get politically motivated if they don’t know what’s happening? To date, the single most important organizational initiative that Local 79 has undertaken in the two years since the last strike has been redesigning its website (though even the members only portal offers less information than one can get in the Toronto Star). Besides Local 79’s “Taking Care of Toronto’s” bus, radio and television adds, the union has remained virtually silent in the media, for example, failing to come out against Councillor and chair of the Community Development and Recreation Committee Giorgio Mammoliti‘s plans for studying the contracting-out of childcare and recreation services.

Once again, most members are unaware of the Local’s proposals going into collective bargaining, few, if any, educational materials are available to members or the public, and beyond stewards, no picket captains have been trained. Further, and most importantly, members are not being mobilized to make the connections between the services they provide and the communities they serve.

With President Ann Dembinski set to retire at the end of the month, will incoming President Tim Maguire step up to the task and create a bolder public image? Will the union rely less on winning over the so-called ‘mushy middle’ set of councillors – we’ve seen the failings of this approach clearly in 2009 and, more recently, with the contracting out of a portion of garbage and snow removal? Rather than relying on a business unionist approach to collective bargaining, executive members should be focusing on maximizing input from its membership and making the connections to the communities affected by privatization and cutbacks.

Strategy Moving Forward

On this note, we need to be clear of the limitations of Local 79/416’s past job-action strategies which relied in good part on filling dump sites and then preventing trucks from leaving waste facilities. Besides the public’s obvious frustration, a majority of workers do not work in waste disposal which meant, for example, that part-time/seasonal recreational staff, building inspectors and administrators with little to no experience with waste management, were tasked with shutting down these facilities and devoting their energies in arguably futile ways.[2] Perhaps there’s a way of using these highly skilled workers’ knowledge and abilities in ways that demonstrate their important contributions to city services? There were certainly other picket lines throughout the city, such as at social services centres and councillors’ offices, but maybe there are new forms of strike action that could reorient the publics’ perception away from the stigma of a ‘garbage strike’ and toward a ‘public services strike’ or a ‘strike against privatization.’ Locals 79 and 416 are both very diverse unions with public health nurses and educators, health inspectors, child and elder care workers, by-law enforcement officers, building inspectors, court and social services administrators, water treatment, Emergency Medical Services, housing, road maintenance, animal services and so on. But maybe this is not as well known as it should be. Is there a way of targeting and demonstrating the other services that these workers supply? In other words, is there a way of utilizing striking workers so that a broader connection could be made between services and communities, privatization and public goods?

Let’s consider child care and recreation (something I’ve been involved with as a part-time employee with the city of Toronto over the last decade). Ford has been very clear in suggesting that Toronto’s 24,000 child care spaces should be privatized. He recently moved to eliminate 2000 subsidized spaces that were previously cost-shared with the province. As such, affordable child care remains one of the most sorely needed services in the city (and the country) with nearly 20,000 children still wait-listed. With over 650 city-subsidized child care centres in the city, perhaps workers and users of those services could come up with new and creative ways of continuing to provide some interaction with children in need of care, youth, adults and the elderly in the event of a lockout or strike. This may include after-school recreation at supportive schools, family events at city parks and public spaces, reading circles at union headquarters, coffee shop talks, flying squads that engage with the public on transit or at malls, outdoor art exhibits and so on.

“Why not reclaim or occupy community centres as central spaces of the community via city provider-community user alliances?”

Still further, since community centres are located at the heart of various neibourhoods, they serve as important spaces for the exchange of information and discussion. Why not reclaim or occupy community centres as central spaces of the community via city provider-community user alliances? This could bring together issues related to child care, recreation, libraries, arts and culture, and connect those to waste disposal, road maintenance and public health for instance. It is unlikely in the event of a strike or lockout that CUPE Locals 79 and 416 could be successful by focussing (once again) almost exclusively on waste collection. The political potential of an ‘occupy’ community centres in coordination with community groups and activists, particularly in light of hundreds of millions in service cuts and over $23-million in new user-fees is just one potential option in a host of other choices.[3]

This might begin with communities demanding more decision making power with the programs and events held at their centres, leafleting campaigns outside recreation and daycare centres, ice rinks, ski hills and so forth, pressuring local councillors and mangers, sit-ins, park protests, educationals and the creation of community caucuses. Since the latter in particular are locally rooted the potential exists for city-wide alliances and the development of an integrated set of demands. In short, any job action should be about most effectively demonstrating the many skills and competencies of city workers in ways that connect them with the communities they are rooted in, and the value in keeping them public. Past experiences show that this is not only possible but most successful.[4]

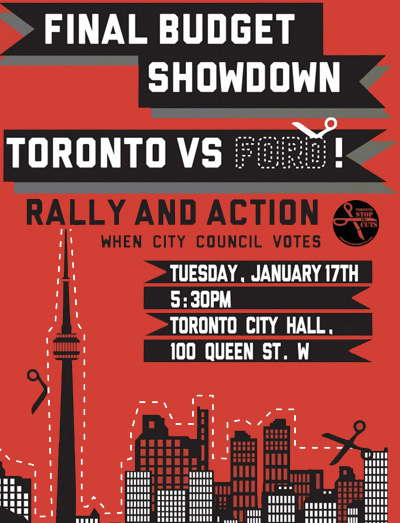

Making the Connections

Finally, in addition to uniting with other unions’ campaigns for public services, there may be ways of inclusively (unlike indirectly with past strikes) coordinating action with community organizations that reinforces existing campaigns, or takes on initiatives the unions are not in a position to do. Without exaggerating current capacities, this may help through our networks to connect with, along with whatever outreach CUPE and the labour council does, activists in other unions and in the community. And rather than only having union-sponsored forums, it might be useful for the unions to reach out to concerned allies like the Toronto Environmental Alliance, Stop the Cuts, Greater Toronto Workers’ Assembly and other groups. Community allies can be more radical in their messages and pamphleteering – as long of course as it supports and doesn’t undermine existing campaigns – than can many confined by official trade union structures. This could be a particularly important and effective space if cultivated collectively. Recent positive developments include CUPE Ontario’s Keep Toronto Public community meeting (although unfortunately only open to CUPE members), the Stop the Cuts Final Budget Showdown, the recently founded Public Transit Coalition, and Social Planning Toronto’s Together Toronto campaigns.

Building our movements in ways that mutually reinforce critical struggles in and around our unions works on at least three intersecting levels: (1) Building the capacities of the entire union to fight back against concessionary demands, and demanding more from our leadership; (2) Developing a movement inside the union that pushes for enhanced democratic participation and control, a radically feminist, antiracist, class-struggle oriented political praxis, and engaging with struggles that affect our communities. (3) Building up a cadre of workers and activists that embody intellectual understanding and are active.[5]

The City of Toronto has been in a steady state of decline in the quality of its public planning and services and social infrastructures for several decades now. In many respects, Toronto now has the shoddiest public spaces and infrastructure of any major North American city, even while growth pressures strain existing capacities. The foremost strategy of the Ford Administration and neoliberal urbanism is to try to make do with even less public spaces, and to leave as much room as possible for market forces to accommodate the continual pressures of urban growth.

The central obstacle in the way of this strategy further advancing is city workers and their collective union organization and the communities of users who depend upon the services they provide. Toronto civic workers face a historic test, which may well set a precedent nationally, given the pivotal place of city workers in public sector unions. Given the push for austerity across all levels of government, public workers and services are under attack from all angles. In appeasing the interests of capital by all too familiarly demanding that working-class standards of living further decline, the battle lines have been drawn and the forces of attack readied. Time will tell if a major resistance is in the cards. •

Endnotes:

1.

For an analysis of Ontario’s push for austerity see Carlo Fanelli and Mark Thomas, “Austerity, Competitiveness and Neoliberal Redux: Ontario Responds to the Great Recession.”

2.

More than a month into the strike the ineffectiveness of trying to fill waste management facilities became all the more clearer. While some facilities were certainly filled to capacity after six weeks, and communities up in arms about hazardous waste seeping into parks and putting their communities at risk, other facilities near industrial areas had the space to keep piling waste for at least another month. Also, given the utter chaos and disorganization that marred most picket lines, rather than engage with those being affected by the strike, workers themselves had little information as to why we were on strike. See Julia Barnett and Carlo Fanelli, “Lessons Learned: Assessing the 2009 City of Toronto Strike,” Bullet No 298.

3.

These suggestions arose through informal talks with friends and family members. For instance, should job action be taken, with parts of snow plowing recently contracted-out (and more on the horizon) what if the unions’ strike headquarters decided to put together a snow-plowing unit that plowed the driveways and sidewalks of the elderly and disabled, or in communities more generally. This would give those whose services have been affected by the strike and those whose jobs have been affected an opportunity to discuss what’s at stake and begin making those connections with others. Since Animal Services is an important part of the city, what if workers held ‘animal appreciation days’ and brought their animals out to the picket lines for morale and to publicize the other services we supply, or offered health and fitness assessments provided by professionals. What if recreation workers like hockey or ski instructors held mini-camps in parks or community centre parking lots. These are just a few small-scale ways more efficient use of workers might be had, rather than having them stand limitedly on a side-walk.

4.

For example, striking museum workers in Ottawa and Gatineau put together regular cultural events that normally would have taken place inside the museum, but held them outside instead. These events were open to the public and provided the workers with an opportunity to organize and work together on the picket line in a fulfilling way. The successful execution of the events, such as the one honouring veterans on Remembrance Day and the “picket line tea party” held in celebration of Prince Charles’ visit to Canada contributed in a substantial way to workers’ ability to maintain their spirits throughout the strike. The events also demonstrated the skill and creativity of workers to the public, as well as presented them as a valuable and productive force. This was especially clear when the Museum of Civilization opened the “Afghanistan: Hidden Treasures” exhibit and the workers created their own featuring themselves and entitled “Striking Treasures.” As striking workers gained confidence through concerted action, and the support of the community mounted, there was a clear turn toward class-struggle unionism as the connections between the employed and unemployed, communities and workplaces, became all the more clearer. See Priscillia Lefebvre, “Post-Strike Musings: Assessing the Outcome of the Museum Workers’ Struggle.” (For an updated and expanded version see the latest issue of Alternate Routes). See also Hilary Wainwright, “Resistance Takes Root in Barcelona.”

5.

See also Greg Albo and Herman Rosenfeld, “What Should We Do To Help Build a New Left?,” Relay No. 28, October 2009.