Tunisia’s Ongoing Revolution

An eventful two months have passed since mass protests toppled former Tunisian President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali – largely out of the media spotlight once the revolution spread to Egypt, but with great importance for the struggle for democracy and justice, in Tunisia and beyond. In December and January, a nationwide movement emerged in Tunisia, led by workers, students and the unemployed, calling for the hated autocrat to go. After just four weeks, the Tunisian people achieved what had seemed impossible: they challenged a 23-year dictatorship backed by a massive, brutal security force – and won. In doing so, they also exposed the complicity of the French and U.S. governments, which were both long-time allies and defenders of Ben Ali’s corrupt regime right through his final days.

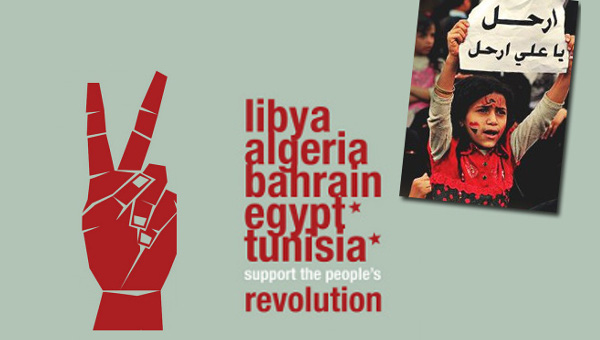

When Tunisians’ nonviolent demonstrations forced Ben Ali to flee to Saudi Arabia on January 14, the victory immediately gave confidence to emerging protest movements across North Africa and the Middle East. In Egypt, where a struggle against President Hosni Mubarak had been brewing for over a decade, the lesson was clear: if Ben Ali and his security forces were not invincible, than Mubarak could be ousted as well.

Mass demonstrations began in Egypt less than two weeks after Ben Ali fled, and 18 days later, Mubarak joined Ben Ali in the dustbin of history.

Protests Spread

The economic clout and geopolitical importance of Egypt and Libya, where the U.S. and European governments have gone to war, will likely keep these countries at the center of the media spotlight.

But Tunisia provides important lessons for anyone who hopes to learn from the struggles, debates and conflicts within an unfolding revolutionary situation. In particular, Tunisia offers insights into what it means for hundreds of thousands of people, if not millions, to actively take part in trying to transform society from the bottom up.

The movement against Ben Ali was driven in large part by demands for democratic political reforms and an end to the country’s oligarchic rule. But growing anger over soaring food prices, inadequate wages and widespread unemployment – especially in the interior of the country – fueled the struggle as well.

Thus far, the interim Tunisian government, which replaced Ben Ali’s administration, has proven hostile to enacting reforms that would significantly alter Tunisia’s economic inequality. New political freedoms have been won, but these incredible victories have only come about because the interim government has been faced with protests and workers’ strikes – on an almost daily basis.

In the process, successful actions organized by both workers and the unemployed have gone beyond the political limitations imposed by the interim government. As those most exploited in Tunisia take matters into their own hands, they raise the possibility of working class people playing a more fundamental role in setting the economic and political priorities of the country. Furthermore, with political opposition parties just now emerging from decades of illegality, many perspectives, including radical and socialist ideas, rapidly gained a new hearing.

As one New York Times reporter observed, “Avenue Habib Bourguiba, the broad thoroughfare in central Tunis named after the country’s first president, resembles a Roman forum on weekends, packed with people of all ages excitedly discussing politics.”

If anything, the toppling of Ben Ali has proven to be only the opening round in a revolution that is now involving even greater numbers of Tunisians, who are actively and collectively tackling larger questions about what to do next.

Chalenging the Status Quo

Ben Ali and his second wife, Leila Trebelsi, were the most visible representatives of the government’s ostentatious and thuggish rule. Their departure emboldened many Tunisians who felt, for the first time, that through their actions they had been able to play a direct role in challenging longstanding inequality and subjugation.

Any hope for significant change would be nearly impossible without clearing out all those closely tied to the former administration, as well as the old ruling party, the Rassemblement Constitutionnel Démocratique (RCD). Thus, demonstrations and workers’ strikes over the past two months have continued unabated, primarily targeting politicians, police chiefs and business executives still desperately trying to cling to power. A popular slogan has aptly captured the difficult task faced by protesters: “The dictator has gone, but the dictatorship is still here.”

However, on March 7, Tunisians moved one step closer to removing the remnants of the old government. In response to ongoing demonstrations, interim Prime Minister Beji Caïd-Essebsi announced that he would be forming a new temporary government free of any members of the former regime. On the same day, he disbanded the long-feared secret police used by Ben Ali to monitor, torture and imprison opposition activists.

These gains did not come easily. Initially, Mohammed Ghannouchi, an accomplice to Ben Ali who had served as Tunisian prime minister since 1999, took the reigns of the interim government. Similarly, the acting president, Tunisia’s speaker of parliament, Fouad Mebazaa, is another erstwhile RCD leader.

While Ghannouchi promised new elections in line with constitutional guidelines, he refused to set a concrete date after pushing them back to September. Even more offensive, in his first interim cabinet, he reserved all major ministries for previous Ben Ali appointees. Not surprisingly, Ghannouchi is known among protesters as “Mr. Oui Oui,” a derisive play on words mocking his history as a “yes man” for Ben Ali.

Attempting to maintain some shred of legitimacy, these former RCD leaders resigned from their disgraced party soon after Ben Ali’s fall. But protesters dismissed this purely symbolic gesture and continued to press for an interim government free of all former ruling party politicians.

In response, representatives from the General Union of Tunisian Workers (UGTT) and another opposition appointee resigned from the first interim cabinet. In late January, Tunisians began a new round of daily protests, managing to break through police barricades and barbed wire in the capital of Tunis to march directly on Ghannounchi’s office, until they faced a stand-off with the Tunisian army. On January 22, approximately 2,000 police officers joined the demonstrations, rather than fire on them.

Caravans of unemployed Tunisians from cities and towns in the interior of the country continued to descend on the capital in defiance of curfew regulations. Over the past two months, many remained camped out in the Qasbah section of Tunis, where federal government buildings are concentrated, determined not to leave until all former RCD members were banned from the administration.

Tunisians have also taken it upon themselves to remove symbols of Ben Ali’s mafia-like rule. At one demonstration, a state employee used steel cables to begin tearing down the letters marking the old RCD headquarters. Outside of the capital, thousands of Tunisians also visited the opulent homes of the former ruling family, taking with them whatever useful building materials and furniture remained – or simply marveling at the grotesque excess. The façade of one mansion was spray painted with the words: “This is the people’s home.”

Faced with resilient demonstrations, Ghannounchi and his ministers conceded a number of reforms to the protesters. Some of Ben Ali’s extended family, former ministers and the former heads of both the police and presidential security forces have been arrested. All previously banned political parties are now legally recognized, and the transitional cabinet has proclaimed a general amnesty for all political prisoners.

At the beginning of February, interim Justice Minister Lazhar Karoui Chebbi claimed to have released over 2,000 inmates held by the old regime, many of them political prisoners. But activists remain unsatisfied, as hundreds of Tunisians remain jailed under Ben Ali’s bogus “anti-terrorism” laws.

Taking a cue from the U.S. “war on terror,” the regime used these repressive statutes to broadly target any political opposition, in particular, members of Islamist and socialist organizations. When Chebbi attempted to appease protesters by publicly declaring plans to extradite Ben Ali from Saudi Arabia in order to stand trial, family members of detained Tunisians surrounded the minister, demanding the release of their loved ones.

Some of those political prisoners released from prison in recent weeks have begun documenting the brutality they faced. Testimonies have now revealed that detainees were tortured not only by Tunisian Interior Ministry agents, but also by interrogators from the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), which worked closely with Ben Ali.

Interim Government

Still unable to quell the resistance to his rule, at the end of January, Ghannouchi reformed his interim cabinet, reducing the number of former RCD members from 10 to just three, and promising that he would leave politics as soon as new elections took place. While few Tunisians were satisfied with the continued involvement of leaders from Ben Ali’s regime, the announcement of the new interim government initially caused the size of demonstrations to shrink.

Tunisian army Gen. Rachid Amal, popular for siding with the protesters during Ben Ali’s final days, asked protesters to accept the newly announced cabinet. Amal has declared that the Tunisian military will not directly intercede in the political process, but his appeal for calm was precisely the kind of intervention that helped Ghannouchi and his RCD allies momentarily regain their footing.

However, the announcement also exposed the fissures between some opposition and union leaders who, like Amal, encouraged Tunisians to accept Ghannouchi’s promises – and the vast majority of the protesters who rejected Ghannouchi outright.

On February 5, hundreds of people surrounded the police station in the town of Kef and the demanded the resignation of its chief, a Ben Ali ally. Police shot and killed two protesters and left 17 injured, but the police chief was arrested and the interim government found itself once again on the defensive. Attempting to assuage anger, the interior minister, Farhat Rajhi, declared the dissolution of the RCD the next day. Less than a week later, a Tunisian judge ordered the party to be dissolved and its funds confiscated.

Shortly thereafter, Foreign Minister Ahmed Ounaiss had to resign when his staff refused to work with him any longer. According to one Foreign Ministry employee, Ounaiss “was not worthy of the revolution” after he praised French Foreign Minister Michelle Alliot-Marie, a key supporter of Ben Ali.

Toward the end of February, mostly young, unemployed Tunisians reoccupied al-Kasbah Square in Tunis. Frustrated with the slow pace of change and Ghannouchi’s refusal to step down, oppositionists and trade unionists organized the largest demonstrations of the revolution on February 25. Between 100,000 and 200,000 people marched in Tunis, while another 100,000 took to the streets in the Sfax, an important industrial city, and site of multiple general strikes since December.

The weekend became a bloody one – with Human Rights Watch reporting that police officers and security forces beat protesters with the aid of “scores of young men in street clothes, some of them masked, clutching clubs, wooden planks and table legs.” The RCD may have been officially dissolved, but the fragmented regime showed that it was still capable of unleashing a flurry of violence and intimidation. Five people were murdered and hundreds injured.

The brutality recalled the struggle against Ben Ali, when police and security forces killed over 200 demonstrators in just four weeks. But now, new attacks were taking place under the command of the interim government, and many Tunisians’ patience had run out. By Sunday, February 27, protests re-emerged, and Ghannouchi was forced to resign.

Ghannouchi’s fall was yet another embarrassment for the U.S. government. Just a week earlier, Sens. Joseph Lieberman and John McCain met with Ghannouchi on a diplomatic mission, praising the interim prime minister and offering their support to his administration. The visit showed that U.S. leaders are focused on finding a willing collaborator to step into Ben Ali’s shoes, and have little interest in listening to the demands of the Tunisian people.

Interim President Fouad Mebazaa has named Beji Caïd Essebsi as the country’s new prime minister. The 84-year-old Essebsi is a lawyer and was a former minister under Tunisia’s first president, Habib Bourguiba, but found himself politically marginalized during Ben Ali’s rule.

Essebsi’s first moves are a promising response to the protests: dissolution of the state secret police, and the appointment of an interim government free of RCD politicians from Ben Ali’s administration. Furthermore, Essebsi appears to have ceded another of the protesters’ major demands: the election, in July, of a constituent assembly to draw up a new national constitution. This has been a slogan raised by many left-wing parties as well as Ennahdha, the country’s largest Islamic party, all recently emerging from years of illegality.

However, Essebsi is an experienced political operator and his promises should be acknowledged with great caution. He honed his administrative tactics under the one-party rule of Bourguiba, and is not connected to the movement in the streets. As Alain Pojolat wrote for the French paper Tous à nous, Essebsi is as “cut off from social reality as his predecessor.”

In a recent speech, Essebsi has implied that some former RCD leaders should play a role in future political decisions, and that criticism of the security forces has been overstated – a ridiculous claim to make as Tunisians still mourn those killed by police in recent weeks.

Solidarity and Independent Self-Organization

Still, with one of the main goals of the demonstrators finally met, the atmosphere in the country has been celebratory. Many opposition leaders are now hastily preparing for the July elections, and those who have taken to the streets in the past four months will likely take part in these campaigns.

However, since December, Tunisian society has fundamentally changed in a way that cannot be measured solely by observing official political reforms and appointments. For many people, especially workers, the importance of solidarity and independent self-organization has become a crucial point of pride.

During the 48 hours immediately following Ben Ali’s departure, Tunis and other cities became the sight of a bloody last-gasp attempt by security forces to sow confusion, fear and division. Even those Tunisians uninvolved in the protests now became the target of beatings, shootings and sniper assassinations at the hands of well-armed thugs still loyal to the ruling clique.

However, urban residents rallied together to defend themselves, especially in poorer neighborhoods that bore the brunt of the police backlash. Young men, along with some young women, worked together setting up roadblocks against intrusion and harassment by security forces loyal to the RCD. They exchanged cell phone numbers and worked in shifts, even during the state-imposed nighttime curfew.

Wary of being harassed for violating the curfew, neighborhood activists in Tunis reached an agreement with sympathetic army soldiers: those at the roadblocks wearing white t-shirts would be allowed to remain out past curfew.

With municipal workers temporarily unable to perform their duties, neighborhoods also came together to organize collective street cleaning and garbage removal. Bakers in Tunis limited each customer to five baguettes, in order to prevent hoarding by their better-off customers, while fruit and vegetable sellers put up signs on their carts inviting passers-by to take produce even if they couldn’t pay. Farmers from outside of the capital began to go door to door, offering each household a liter and a half of milk.

Within a week of Ben Ali’s fall, a spirit of collective responsibility and organization began to emerge on an even larger scale. Across the country small cities and towns, such as Siliana and Sidi Bou Ali, came together to elect provisional councils charged with organizing local affairs. With the RCD collapsing, these elections often took place at mass meetings of thousands in town squares, where friends and neighbors became nominees for various committees: liaisons with the army, cleanliness, logistics and even “awareness” and “orientation” committees.

In February, the interim government attempted to stifle these democratically elected committees by appointing new regional governors across the country. As socialist journalist Jorge Martín reported, 19 of the 24 new appointees were connected to the RCD, causing local protests and strikes to break out immediately in regional capitals. Within just a few days, demonstrators had expelled five of the new governors.

In response, the interim government agreed to consult with the national Tunisian trade union federation, the UGTT, before announcing new governors. While this compromise is an attempt by the interim administration to gain political legitimacy through the approval of the trade union leadership, it also reflects the very real power that workers have been exhibiting in the streets and workplaces of the country.

Most crucially, Tunisian workers have begun to assert control over key enterprises, especially those formerly under partial state control and those owned by the Trebelsi family – a murky distinction in many cases. The political power of the former regime was tightly intertwined with its direct domination of the national economy.

In cooperation with the International Monetary Fund, Ben Ali privatized 160 national services and industries during his reign, with most being sold off on the cheap to those in his close family circle. WikiLeaks recently released a 2006 memo from the U.S. ambassador in Tunisia providing a detailed picture of how each family member monopolized control of certain industries, establishing, in essence, personal economic fiefdoms. The memo estimated that half of the country’s economic elite was related to Ben Ali.

Thus, workers have played a key role in dislodging members of the old regime by challenging their economic grip on the country.

Within days of Ben Ali’s flight, the nearly 700 workers at the major Tunisian insurance company, Société Tunisienne d’Assurances et de Réassurances (STAR), went on strike, and forcibly expelled their CEO from his office while singing the Tunisian national anthem. These actions were repeated by workers at Tunisia’s national oil distribution company, Société Nationale de Distribution des Pétroles (SNDP), where the CEO was known to have granted the Trebelsi family control over a number of profitable gas stations.

Executives soon found themselves escorted out of their offices at the National Agricultural Bank (Banque Nationale Agricole) and Tunisie Telecom. The workers at Tunisia Telecom went on strike in mid-February after they received documentation of the salaries of the 65 highest-paid company executives.

These are major companies, with SNDP and Tunisie Telecom ranked as the fourth- and fifth-largest companies in the country. The head of Tunisia’s tax office was also booted by his employees, and at the Banque de Tunisie, workers prevented managers from returning to their offices, in order to stop the flight of bank funds and the destruction of incriminating documents and files. Journalists at La Presse de Tunisie, a newspaper formerly under the control of Ben Ali’s regime, elected their own editorial boards from among their co-workers, and informed executives that they will no longer control paper’s tone or content.

By ousting their bosses, workers have not only scored important symbolic victories. They have also started to root out the former economic dominance of the Ben Ali’s family, thereby simultaneously weakening the former cabal’s political influence of over the interim government. By taking these first steps toward democratic control of their workplaces, Tunisians are raising the possibility of a revolution that could provide much more than electoral freedoms.

While these actions reflect a new level of confidence and militancy among Tunisian workers, it is not surprising that many were already at least nominally organized under the auspices of the UGTT. Despite decades of complicity and accommodation with the regime on the part of the national UGTT leadership, the rank and file of the union federation has not hesitated to challenge their bosses or the regime over the past few months.

In recent discussions, both Alhem Belladj and Nizar Amami, members of the Ligue de la Gauche Ouvrier (League of the Left Worker) in Tunisia have argued that the initiative being taken by rank-and-file activists and locally elected union leaders should come as no surprise. As Amani points out, “This is not an accident, because for several years now, we have seen federations calling strikes without the approval of the general secretariat.”

The current escalation of workers struggle has opened a debate within the Tunisian labour movement. After Ghannouchi announced the formation of the new interim cabinet, UGTT leaders voted not to join the government, preferring to stay among the left-wing opposition. However, the Administrative Council, in a highly contentious vote, simultaneously decided to accept Ghannouchi as the temporary head of the government.

Thus, some members of the UGTT bureaucracy tried to maintain credibility with the rank and file by refusing to join an interim government overseen by a former RCD apparatchik, but simultaneously pleaded with demonstrators to temper their protests of Ghannouchi.

This willingness to compromise was immediately challenged by many local sections of the trade union federation. For example, UGTT workers in Sidi Bouazid and Sfax moved ahead with plans for short-term general strikes against the interim government, and there is now a petition calling for the election of new national union leadership. Unionists have marched on the headquarters of the UGTT to demand that General Secretary Abdesselem Jerad resign. After collaborating with Ben Ali through his final days in office, Jerad has now been pressuring local unions to end strikes and return to work.

Hafaiedh Hafaiedh, general secretary of the Tunisian Union of Elementary School Educators pointed out that the elected representatives of many of the largest and most active unions, including his own, all voted against the proposal to accept Ghannouchi’s government. These unions, along with the regional federations in places like Sfax, Bizerte and Jendouba all played a key role in forcing Ghannouchi’s resignation.

With workers taking matters into their own hands, organizing general strikes and expelling the executives of major enterprises, it is likely that the UGTT will continue to be pushed by its members to play a role in organizing opposition to any signs of retreat from the new interim government.

Since the legalization of previously banned political opposition parties at the end of January, those organizations most brutally repressed by Ben Ali’s regime have been slowly regrouping. Essebsi’s recent promise to hold elections for a constituent assembly has been a key victory for many of these emergent parties.

One of the organizations pushing most forcefully for a new constitution has been the “January 14th Front,” a coalition of eight left-wing groups, which is most visibly led by the Tunisian Communist Worker’s Party (PCOT).

The PCOT’s adherence to a Stalinist political tradition is a critical impediment to building a truly democratic mass organization, but the direction and influence of it and other radical parties may shift in the face of a constantly changing political situation. A rally organized by the January 14th Front drew as many as 8,000 people in Tunis in mid-February, showing a large opening for radical politics.

The question of a genuine socialist tradition in Tunisia has often obscured by the membership of Ben Ali and the RCD in the Socialist International, a body that includes France’s Socialist Party and the British Labour Party. In fact, it wasn’t until January 17, after Ben Ali had been deposed by mass demonstrations, that the Socialist International finally decided that perhaps the dictatorial RCD shouldn’t be included in a formation that calls itself “socialist.”

The January 14th Front provides a possible alternative to the absurd notion that the RCD could have represented “socialism” in Tunisia, but the coalition is still in the process of working out its positions, as each constituent group struggles to reorganize after years of illegality.

In a recent speech, Alhem Belladj, from the League of the Left Worker – a member group of the January 14th Front – stated that the organization had begun to assert itself as an explicitly anti-capitalist formation. However, she cautioned that the nascent grouping was only beginning to raise more concrete economic and political demands. In the face of a deep crisis of unemployment and rising costs of living, the potential exists for socialist ideas and ideas of workers direct control of the economy to become concrete.

Also in the process of reforming is al-Nadha, the main Islamic party in the country. Sheikh Rachid Ghannouchi, a long-time leader of al-Nadha, returned to Tunisia in late January, after two decades of forced exile. After a strong showing in the 1989 legislative election, over 30,000 al-Nahda members and supporters were jailed by Ben Ali’s government during the 1990s.

Upon Rachid Ghannounchi’s return, he called for a more thoroughly democratic reconstruction of the national government, including a new parliament and constitution. Despite the predictable U.S. hysterics about “Islamist” parties, he and the party’s new secretary general Hamadi Jebali have both insisted that al-Nahda is committed to maintaining a democratic, pluralist state and legal system.

Lately, U.S. press outlets like the New York Times have ignored most of the major protests shaking Tunisia. Instead, they have used their minimal coverage of events in the country to largely propagate Islamophobic fears regarding the direction of the revolution. In particular, after a protest in Tunis against city brothels led by a small group of demonstrators, the U.S. media has raised alarms about the potential future treatment of women.

Completely ignored in this empty speculation is the significant leadership role being played by women workers in the Tunisian protests, especially in municipal labour strikes. As in the struggles across the region, sexism has been dealt a significant challenge by the crucial collaboration of men and women in the face of repression. Media claims of an impending wave of women’s oppression at the hands of Islamic parties also ignore the fact that al-Nadha’s leaders have been clear that they are not calling for the implementation of restrictive policies, such as the forced veiling of women.

Perhaps more importantly, al-Nahda, like all of the parties reforming after years of repression, has only a small base of support. The political field in Tunisia is wide open at this point. While it once had a strong foundation, al-Nahda will ultimately be limited by the party’s continuing commitment to maintaining capitalism in Tunisia. While leaders have raised criticisms of the extreme concentration of welath that marked Ben Ali’s regime, they have been reluctant to propose concrete economic changes to deal with inequality.

As Tunisian postal worker and trade unionist Nizar Amami points out, the revolution has thus far been pushed by mass protests and strikes because of the relative non-interference of the army – a starkly different situation than what the people of Libya and Bahrain are facing. But the army has not been passive, clashing with protesters after the appointment of new governors in February and at other demonstrations over the past month.

The upcoming elections and the writing of a new constitution will be important milestones in the Tunisian revolution. However, it is unlikely that these political changes will confront the deep material inequity present in Tunisian society.

This is why the recent wave of workers expelling their managers, strikes for more jobs and major pay increases, and the direct democracy taking place in town squares across Tunisia have all created important new possibilities for the revolution.

Whether radicalizing workers will be able to discard the conservative leadership of the national trade union federation, and whether the January 14th Front could come to represent the aspirations of the Tunisian working class and unemployed is still undetermined. With former activists just now being released from jail and political breathing space opening up for the first time in decades, new organizations are likely to emerge in the near future.

The struggle for the future of Tunisia is ongoing and is likely to continue over the course of many more months. For the time being, momentum remains with the Tunisian demonstrators – women, men, young, old, employed, and unemployed – who continue to taunt their former leaders with the chant: “You stole the country’s wealth, but you will not steal the revolution.” •

This article first appeared on Socialist Worker.