The Tekel Strike in Turkey

The strike of Turkish workers across the winter of 2009-10 at Tekel, a former state enterprise in the tobacco and alcoholic beverage sector, has attracted the attention of the left and unions around the world. The Tekel workers have demonstrated incredible tenacity and courage in confronting layoffs, flexibilization, and remuneration cuts that have been the result – as well as the intent – of the privatization process. The strike has animated the Turkish union movement, and given renewed impetus to the class struggle in Turkey.

Although the struggle has many features specific to the Turkish context, it has gained wider resonance for the union movement internationally. Struggles over public sector austerity and restructuring are moving to the centre of the political stage as ‘exit strategies’ from the financial crisis begin to set in. Indeed, these conflicts have already burst onto the streets of Athens, Dublin, Lisbon and San Francisco. And they will continue to spread over the coming year. Workers and the left around the world can draw inspiration from the Tekel workers’ struggle. The Bullet here presents two reports, from Sungur Savran and Gülden Özcan, on the current phase of the Tekel strike.

The “Sakarya Commune” Wins the First Round!

After 78 days of resolute and militant fighting, the heroic battle of the Tekel workers of Turkey has now entered a new phase. At the end of January, the government issued a decree that involved some minor improvements to the new employment status of the workers, giving them a month to make the transition to this new status or to lose their jobs all together. The workers and their union refused this new offer, since the casual nature of the employment status remained despite the improvements (the workers could be sacked at the end of 11 months of employment in their new jobs.) On March 1st, the penultimate day before the term recognised by the government expired, the Council of State, a high court in the French tradition that oversees administrative decisions, decided to stay the execution of the government decree, on the grounds that the 30-day period given by the government to make the choice was “unnecessarily restrictive.”

Squeezed between the alternatives of having to accept a status against which they had been fighting for more than two and a half months and joblessness in a country where the official unemployment rate is 14%, with real figures reaching up to 20%, and threatened by the government with eviction from the tents that they had set up in the heart of Ankara, the capital city, the workers rejoiced at having gained a reprieve of unspecified length to carry on their fight. The union they belong to decided that, after 78 days in Ankara, the workers would go back to their home towns to return to Ankara on April 1st to start the struggle anew. So we have entered a new stage that is extremely critical for the future of this fight, which has given an electrifying impetus to class struggle in Turkey.

The Background

Before assessing the present situation and the prospects for the future, it would be in order to summarize the events that unfolded within the last three months so as to give the reader a taste of the significance of this struggle. As we have earlier written, Tekel is a former state economic enterprise of tobacco and alcoholic beverages that was privatized in early 2008 despite the militant struggle of the workers against privatization. The tobacco factories were sold to British American Tobacco, which sacked 12,000 of the workers and closed down the many factories around the country except one, thus making it clear that its real purpose was to conquer the large domestic market of Turkey. The government proposed these workers jobs in other public sector establishments paying roughly half their earlier wages, but more importantly with no job security or social rights. The workers revolted against this, organizing on 15 December 2009 a march on Ankara from 21 provinces of the country. Having survived the ferocious attack of the police on the fourth day of their action in Ankara, the workers spent the next four weeks in front of the building of the trade-union confederation to which their union is affiliated, Turk-Is, carrying out protests and impromptu small demonstrations. Having gained the support of broad sectors of the working class and society at large and having voted unanimously to continue their struggle, the workers forced the Turk-Is bureaucracy to take action, one-hour work stoppages all around the country and a big demonstration in Ankara on January 17th, during which they invaded the podium to call for a general strike (not a legally recognised right in Turkish legislation).

When the negotiations between the government and Turk-Is stalled, the bureaucracy was forced, under the pressure of the force of the workers’ action, to decide, together with other workers’ and public employees’ confederations, on a one-day “solidarity strike” – a general strike in disguise, on February 4th. However, not one single confederation, including the left-wing DISK and KESK, moved a finger to really organise the general strike, so this turned out to be one only in name. There were sporadically workplaces that did spontaneously stop work on that day, but the real action was on the streets. In all the 81 provincial capitals of Turkey, as well as many small towns, there were demonstrations, more than a hundred thousand workers all in all coming out on the streets in support of the Tekel workers. This show of solidarity, despite the machinations of the bureaucracy, forced the government to step back and concede the improvements mentioned above, which nonetheless fell far short of the major demand of the workers, i.e. job security.

The “Sakarya Commune”

In the meanwhile, after the January 17th demonstration, the workers gradually set up tents in the neighbourhood, called Sakarya, in which the Turk-Is headquarters is located. This soon became a full-fledged “tent city,” sprawling across several streets in the heart of Ankara. The workers held night vigils in these tents, taking turns to sleep on makeshift beds, discussing among themselves and with their visitors, mostly organised and unorganised socialists, other workers and labourers, and people from all walks of life. Mornings were quieter as many workers rested in those hours. And in the afternoons and evenings there was constant action, torchlight marches etc. There was incessant political debate. The tent city in Sakarya turned into a Mecca for all kinds of opposition movements and created an immense impetus for an awakening of class consciousness in all, Tekel workers and visitors alike. Everything was shared, from food to beds to ideas. Socialists, ostracised and marginalised by state and society alike since the military coup of 1980, moved like fish in the sea among the workers. A majority of the Tekel workers, most of whom had been rabidly anti-communist up until recently, embraced the support extended to them by socialist parties and groups, avidly discussed socialist ideas with them and rapidly moved away from the mainstream parties they had supported in the past.

Furthermore, the barriers created by the prejudice of the Turkish workers toward the Kurds (looked upon as “terrorists” and “separatists”) was overcome to a great extent. In the heat of the common fight the Turkish workers embraced their Kurdish comrades and cast away their hostility. Another important element was the presence in Ankara of a considerable contingent of women workers. For families with a conservative way of life, where even women who work outside the home are subjugated to strict control by their husbands and male kin, the sight of women workers from provincial cities spending the night sleeping in beds in shared tents was amazing, even heroic.

The prospect of the Turkish government and the usually brutal Turkish police tolerating a “transgression” like the Sakarya “tent city” would have been unimaginable but for the resolve and the tenacity of the Tekel workers. Such was the force and legitimacy of the struggle that the government did not dare to order the evacuation of the area – which would have been, militarily speaking, an easy task for the police, given the docility of the union bureaucracy. This, then, is what I would call the “Sakarya Commune,” a space of freedom and revolt that lasted for 40 days in the form of a “tent city” and for 78 days in all.

The Reprieve

The period between that caricature of a general strike on February 4th and the beginning of March passed with the manoeuvres of the union bureaucracy to bide their time so that the Tekel workers, exhausted and in desperation, would accept defeat. There was one last big action on February 20th, when professional unionists and shop stewards from around the country, joined spontaneously by many ordinary workers and Tekel supporters, numbering some 30,000, descended on Ankara to spend the night in the “tent city.” Then came the decision of the confederations to stage “another” general strike… scheduled for May 26th! When this decision was announced to Tekel workers, one yelled “2010 or 2011?”

The decision of the Council of the State was partially a product of what we call the “political civil war of the bourgeoisie,” pitting the government against the army and the high courts, the two sides obliquely representing the two fractions of the Turkish bourgeoisie, the well-entrenched Westernist-secular fraction and the rising Islamist one. This has confirmed our prognosis that, were the working-class movement to take bold steps in this conjuncture, the breach between the two wings of the bourgeoisie would give it tremendous room for manoeuvre. However, the court’s decision was also the product of the tremendous popularity and legitimacy of the movement itself and may, in this sense, be considered a partial victory. Round one goes, globally speaking, to the workers, who have returned home unvanquished.

However, this opens a very difficult period. The power of the struggle mainly sprang from the force of the collective unity of thousands of workers from all around the country, men and women, Turks and Kurds, occupying, in a certain sense, the heart of the capital. Back in their home towns, no one will hear of them and there is no overall plan of action for the month of March. This is bound to bring the workers back to a psychology of normalcy from the heights of the excitement of successful and tenacious struggle. The union bureaucracy, now including the workers’ own union, which formerly adopted a much more militant stance than the confederations, seems to be bent on putting an end to the movement.

So the days ahead are full of dangers. But the Tekel workers have surprised everyone so much at previous downturns of the struggle that it is too early to predict a petering out of the movement. Hence April 1st, when the workers return to Ankara, may hold in store a pleasant surprise once again.

Whatever the final outcome of the struggle, though, the Tekel fight has already made history by the immensely militant and resolved spirit of the workers in this age that has so often been dubbed post-modern, by their original and creative modes of action and by the repeated challenge they levelled at the union bureaucracy. It has shown once again that workers learn and gain class consciousness in and through action. It has shown the way forward to the fraternity of the Turkish and Kurdish peoples. Finally, it has also awakened broad layers of the working masses to class consciousness, masses who in effect share the same burden of joblessness, contingent work, low wages and privatizations. These have earned it a well-deserved place in the annals of the class struggle, both in Turkey and internationally. •

“Workers are Teaching, Students are Learning”

Gülden Özcan

Students erected the banner “Workers are teaching, students are learning” on one of the tents where TEKEL (Tobacco and Alcohol Monopoly of Turkey) workers were striking over 70 days in downtown Ankara, the capital city of Turkey.

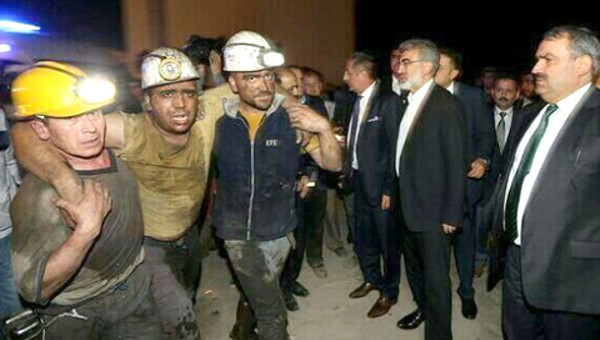

When workers from other cities came to Ankara in mid-December to voice their demands, they didn’t know their stay would last this long. They expected that the government would hear their voices and respect their effort in order not to lose their position as full-time employees of the publicly owned enterprises. But it was not the case. Rather, the police violently intervened as Tekel workers peacefully sought to demonstrate in Ankara. Workers were met with pepper spray, water cannons and were beaten by the police. Shocked and battered, striking workers found shelter in the central building of their union located in downtown Ankara. Then, the story of the seventy eight-day long strike started. They built their nylon tents outside the union building and started to live in these tents under the cold weather. Thousands of their fellow workers came and joined them in the following days. Their numbers swelled to more than 6,000 living in downtown Ankara in their self-made nylon tents.

TEKEL Workers

Having previously been run by the state, Tekel employed 30,000 workers in 110 tobacco processing, 6 cigarette, 19 alcohol beverage production factories, 84 marketing offices, 10 salt producing enterprises, one packaging factory and a silk and viscose factory in 21 different cities across the country. As public sector employees, Tekel workers maintained modest benefits.

In 2002, Tekel shared the same fate as the rest of the state-owned enterprises remaining from the state subsidized economy of the pre-1980 period in Turkey and was put on the fast track to privatization. After they came to power at the end of 2002, the AKP (Justice and Development Party – Adalet ve Kalkinma Partisi) government first divided Tekel into three separate branches (alcohol, cigarette and tobacco), and then one by one sold them off: first alcohol in February 2005, next cigarettes in October 2006 and, finally, tobacco in February 2008.

During the first two phases of privatization, worker layoffs were not in massive numbers as some regulations protected them. They were either relocated in different public sectors with the same rights or transferred to the remaining tobacco processing centres in Tekel. However, in the last phase, in February 2008, the decision for about 12,000 workers employed in the tobacco processing factories was made that they would be laid off over the next two years.

Of course one can ask why these workers had to be laid off instead of working in the same factories with the private owners. However, these privatizations did not have any “reasonable” (even within the reason of neoliberalism) set of regulations that might be expected to serve the aim of improving capacity and developing capitalist enterprises in the country. These tobacco processing factories, for example, were sold with all the equipment, raw materials, installations, yet without the workforce, to British-American Tobacco (BAT). Moreover, with no down payment and a two-year freeze on payments, BAT quickly re-sold the factories to a third party (at a substantial profit) without a single payment being made to the state.

Even though privatization was finalized in February 2008, workers were going to be out by January 2010. In the mean time, workers continued to process stocked tobacco products in these factories. On January 31st, 2010, employees were offered 4/C status.

C-4, as the Workers Call It

4/C stands for item C of the fourth article of the Civil Servants’ Law numbered 657 dated 1994. 4/C was created to employ temporary workers in government jobs that required less than 10-month contract. In 2004, the AKP government approved an amendment to this article that included workers who had been laid-off due to privatization. These temporary contracts have been especially prevalent in education and health care since then. Rather than employing people in full-time, year-round forms of employment, AKP continues to hire recent graduates and health care providers on limited term contracts of less than 10-months.

Tekel workers call this “C-4,” referring to the plastic explosive used to demolish buildings; except in this case, workers livelihoods are being demolished. Some refer to it as a modern form of slavery for the following reasons. Under 4/C workers are limited to between four and ten-month contracts; social benefits are non-existent; employees are barred from any additional outside employment; work-time is dependent upon management provisions; workers are entitled to one vacation day per month; and no overtime pay is granted. Likewise, regardless of age, ability or training, management reserves the right to place workers where they feel is necessary. Moreover, workers cannot register with unions because of the possibility of getting fired or having not renewed their contract in the following year. Depending on their position of employment, workers earn on average between 600, 700 and 800 TL monthly (around $430, $500, $570). Divided into the actual working hours these numbers remain under the minimum wage regulated by the government.

The Other Side of the Coin

It is not only Tekel workers that are suffering from the brutal privatization of Tekel. In the pre-1980 period during the time of state subsidized economy, Tekel was the monopoly that had control over tobacco planting and processing in Turkey. Tobacco farmers like other primary sectors of the economy, received significant subsidization by the state, while remaining especially profitable. As the military regime of 1980-83 moved toward a ‘free market’ system, increased foreign competition began to steadily decrease the market share of domestically produced goods. In 1984 the ban on cigarette imports had been lifted, exposing Tekel to significant competitive pressures. Yet, Tekel continued to dominate the market until 2002, while exporting three-fourths of its tobacco production.

By 2002, tobacco farmers were left without any state support. They were left alone with the global market forces, i.e., European and American tobacco companies. As a result, the number of tobacco farms shrunk, and producers were left with excess supply without a profitable source of sale. These farmers, who have for generations been able to maintain their families, are left with no choice but to leave their villages and migrate to the sprawling cities, thereby joining the mass reserve army of labour. The remaining farmers watch the Tekel workers’ strike and desperately wish them success.

Life in the Tents

For over two years, Tekel workers have resisted against the privatization of their workplaces and the 4/C package. Only after they came to Ankara in such masses and merged their forces, their strength has increased. The solidarity they have shown has become remarkable for general public. In particular, for the left in Turkey, Tekel workers have become the voice of the proletariat that was in great silence for the last two decades. While incidents of workplace militancy have risen, they have been brief and have not garnered much public or media attention. This is similar to Tekel workers in that there had been little media coverage for 30-days into the strike. It wasn’t until 70,000 workers converged in Ankara on January 24th that the corporate media took note of the strike.

Workers have established a little village out of nylon tents in downtown Ankara. Despite the cold winter of Ankara, workers stay tight in these tents and share their workplace experiences. Despite ideological differences and the recent resurgence of Turkish nationalism against Kurds, the solidarity among workers is prominent. Their collective experiences have led to an unimagined camaraderie as Kurdish and Turkish songs have been sang in unison, and workers from fundamental religious backgrounds and former AKP supporters have taken their place in collective working-class resistance grounded in their lived experiences.

Effectiveness of other organized forces has become apparent as the resistance goes on. The left in Turkey was able to mobilize in an effective way around the strike. Halkeveleri (People’s Houses) built their own tent beside the workers’ tents. This tent was later on called “TEKEL University of People” as academics engaged workers in various discussions in this tent. Such interactions between the members of leftist organizations and Tekel workers have helped to narrow the historical gap between working class politics and the workers themselves. Students and youth, few of which have ever witnessed organized working class struggle to such an extent, are mobilizing. In addition, health workers, teachers, academics, artists and, even those traditionally ‘apolitical’ and from a variety of political persuasions, have visited Ankara to show their support. This has included cooking meals, bringing blankets, tea and snacks, and even providing haircuts for workers. As the mainstream media continues to distort the realities of Tekel workers and why they are on strike, the International Labour Films Festival organizers have come together to live-stream the life in the tents through the Internet.

“Funny Games” Played on the Upper Level

Despite the Tekel workers’ commitment to the strike, the AKP government has not stepped back from the 4/C. The great fear of the government is not only Tekel workers, but also some other 200,000 workers who currently work in the state-owned enterprises which are on the list of privatization. If the AKP government steps back from the 4/C now, they will never succeed in employing these 200,000 public employees under 4/C. Moreover, the government fears that Tekel workers will stimulate others to join their cause. Therefore, the negotiated item on the table is not 4/C only, but the future of working class movement.

The unions are not acting in an effective way. The meetings of the Turk-Is management with the government have not come to a solution on 4/C, but after each meeting Turk-Is has tried to leave Tekel workers alone in their struggle instead. Tekel workers’ commitment to the struggle could have been turned into a greater working class movement with the support of the other trade unions affiliated with Turk-Is. Although the four largest unions in Turkey (Turk-Is, DISK, KESK, Kamu-Sen) have announced their support of Tekel workers, they have been unable to come up with a serious action plan. Already frustrated workers have also been confused by the ongoing power games among the executives of their union and unclear position of other unions.

Not a Spectre, but the Vital Reality:

Proletariat on the Stage

Despite these tactics, on February 20th Ankara experienced an unforgettable scene. Over 20,000 people came together and spent the night with Tekel workers. They were chanting, singing, dancing together; it was the voice of working class that is coming onto the stage as a political actor after a long silence. Tekel workers are now teaching again how powerful organized workers can be. The crucial need for a greater working class organization and the need for realist working class politics have become apparent and begun to be discussed more efficiently. In that sense, the Tekel workers have already achieved much although a real solution to their problem will not come soon. •

Gülden Özcan is studying for her doctorate at Carleton University in Ottawa.

Resources: