The Canadian Election and the War in Afghanistan

Conservative Party leader, Stephen Harper, attempted to remove questions about Canada’s role in Afghanistan from debate during the election campaign by announcing the combat role of the Canadian Forces will end, in 2011, if he is re-elected as Prime Minister.

But let’s be clear about what the current combat role entails. Many Canadian political and military leaders claim the current counterinsurgency war will help bring stability, development, democracy, and the liberation of women to Afghans, which will in turn make Canadians and the people of the world safer. However, Canada is participating in a counterinsurgency war using tactics prohibited by international law. Canada is also participating in a global American-led war with obscured geopolitical and economic objectives. Canadian political leaders have put us in this position to curry favour with the United States and benefit a small minority of Canadians – primarily investors in Canada’s military industrial complex, the extractive industries, construction, transportation, communications, and other industries that can profit from war.

None of the Canadian political parties has produced a clearly focused foreign policy that most people in Canada and Quebec can support in good conscience.

During the current election campaign, the leaders of all the political parties have avoided discussing the issues of the war in Afghanistan and its broad implications for Canadian foreign policy in any depth. The NDP, Green, and Bloc Québécois parties have at least produced platforms advocating withdrawal of Canadian combat troops from Afghanistan. The Conservatives and Liberals advocate holding the present destructive course until 2011.

All parties have avoided discussing Canada’s combat role in Afghanistan in any depth for fear of alienating the small but powerful minority of war supporters. Most grassroots support for the war is generally well-intentioned, but, unfortunately, misinformed by the claims of altruistic intent made by the Government of Canada and Canadian Forces. Some grassroots support for the war, however, displays a disturbing trend towards an emerging North American jingoism.

Big business support for the war is profit-driven. The war is transferring billions of tax dollars to manufacturers and service providers in the military/security industries and many other related industries. The war is also opening Afghanistan to foreign investment and could potentially make all of Central Asia far more accessible for North American businesses.

Successive Liberal and Conservative governments have manoeuvred Canada into a subordinated position deeply integrated within America’s global war-making organisation. Canada’s interests have become aligned with American imperial interests. Yet, no leader of a major Canadian political party has asked why Canada is in this subordinated position as a key support of American imperialism, or laid out clear strategies to break from it.

The Financial Costs of Canadian Militarism in Afghanistan

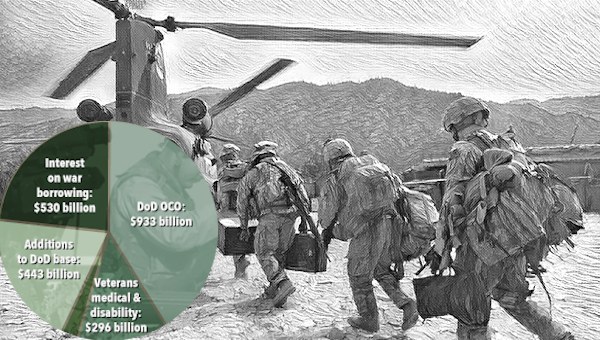

Neither the recent Conservative government nor the earlier Liberal government have been forthright about the priorities for the war in Afghanistan. Even Canada’s Auditor-General, Kevin Page, has had a difficult time getting clear answers from state agencies regarding the costs of the war. Page estimates the cost could reach $14 to18 billion by 2011. The Rideau Institute estimates the costs could balloon to as much as $28 billion.

Canada pledged only $1 billion for development aid for the period 2001-11, little of which, to date, appears to have been spent on substantive human development projects. Independent assessments of Canada’s development role are difficult because the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) and the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT) appear as secretive as the Department of National Defence about how they spend their budgets in Afghanistan.

The gross difference between the Canadian war and development budgets is reflected in the gross difference in scale between actual destruction and reconstruction on the ground in Afghanistan.

It is important to keep in mind that the financial costs of the war borne by most taxpayers are a boom to the corporations profiting from war. Politicians consciously decide to prioritise this economic transfer to war-profiteering corporations over other potential spending in social welfare, environmental protection, and sustainable economic development.

The Human costs to Canadians and Afghans

The body count of Canadians killed in Afghanistan is well publicised in the Canadian media. However, the Department of National Defence is secretive about how many Canadians return from the war with debilitating injuries. The human cost to veterans and their families cannot be accounted. The economic cost to taxpayers could not be accounted by Canada’s Auditor General, because DND has not been forthcoming with its accounts. Canadians know little about the losses suffered by Afghan civilians.

Canadian Forces must be withdrawn from combat not because Canadian soldiers are being killed and injured; soldiers are prepared to sacrifice their lives when they believe their mission is legitimate. Canadian Forces need to be withdrawn from combat because the mission is not legitimate.

Tactics used by the American-led counterinsurgency force, in which the Canadian Forces plays an aggressive part, violate norms prescribed by the Geneva Conventions of War.

American, British and Canadian leaders and NATO officials often express regret for the high levels of Afghan civilian casualties, but routinely blame insurgents for hiding among civilians as the excuse for the deaths, injuries, and property destruction caused by the American Operation Enduring Freedom and NATO forces.

“We are in a different moral category” than the insurgents, said NATO Secretary-General Jaap de Hoop Scheffer, because, he claims, the majority of the Afghan people support the NATO forces (Washington Post, 22 May 2007).

However, the Geneva Conventions of War, amended in 1977 in response to counterinsurgency tactics used by American forces in Vietnam, explicitly forbid the tactics currently used in Afghanistan.

The Geneva Conventions of War state:

“… the Parties to the conflict shall at all times distinguish between the civilian population and combatants and between civilian objects and military objectives” (Article 48); and

“The presence within the civilian population of individuals who do not come within the definition of civilians does not deprive the population of its civilian character” (Article 50-3).

The Conventions do not provide any exemptions for military forces claiming to be in “a different moral category”.

Canadian Forces in Afghanistan use a hundred tanks and an unknown number of even more destructive heavy artillery cannons. When forward operating forces take fire from insurgents, observers report the suspected position of the source of fire to the artillery that is many kilometres behind the forward positions. One shot from a tank or cannon can destroy a home or building and kill or injure anyone nearby. If Canadian artillery forces are not within range, American or British airplanes are called in to do the job. Observers try to determine at a distance whether civilians are in the kill-zone, but ‘collateral damage’ to civilians and their property is inevitable.

If a Canadian police force could bomb a Canadian neighbourhood with impunity, whenever the police suspect an alleged criminal is hiding there, I doubt many Canadians would accept this tactic. Why do we accept it when aimed at Afghans? Why do we accept it when most of the world condemns such a tactic and explicitly forbids it in international law?

When visiting Afghanistan in 2007 as part of a team of independent researchers (read my dispatches), independent observers told us the Canadian Forces do use a “humanitarian” option that sets Canadians apart from the Americans. During large scale search-and-destroy missions, Canadian Forces reportedly will give an evacuation order to inhabitants of a village or specific area. Once the time limit of the evacuation period (often twenty-four hours) has expired, the forces move into the area to search for weapons and insurgents. In order to prevent unnecessary losses soldiers do not search inside suspected buildings, water-wells, food storage structures, etc. Any structure that might house a weapons cache or insurgents is destroyed.

One witness, who works throughout Kandahar with a humanitarian agency, told us that Canadian officers seem truly “mystified” when people “choose” to become refugees after their homes, farms, and businesses are destroyed by the forces that are supposedly liberating Afghans.

Many Afghans believe the West has contempt for Afghans. Innumerable Afghans have suffered through the deaths of loved ones and horrific injuries. Uncounted numbers of people are displaced when their homes and livelihoods are destroyed. Arbitrary home invasions, arrests, detention, torture, sexual abuse, rape, and general humiliation of civilians and loss of autonomy add to the complaints many people expressed about the international intervention. Most people told us that they perceive the NATO intervention as an invasion and occupation of their homeland.

Canada and Great Britain have been the most stalwart supporters of the war, since America’s Operation Enduring Freedom began with its initial invasion on 7 October 2001. The lack of participation by most other states in the counterinsurgency mission is not because other allied militaries are not prepared for combat or because their soldiers are afraid to fight. Other states have resisted participating in the counterinsurgency mission, because the domestic political forces in those states have successfully restrained their military forces from participating in what is widely perceived as a poorly conceived military strategy that violates accepted norms of international law.

Canadian Conservative and Liberal politicians claim that, by fighting in Afghanistan, Canada is supporting its allies. However, in reality, Canada is supporting the U.S. while browbeating more reluctant members of the NATO Alliance to join in adopting tactics of warfare (though these are internationally recognised as illegal)

Canada’s Role in Geopolitics

By going to war in Afghanistan, successive Liberal and Conservative governments have secured a powerful, but nonetheless, subordinate position for Canada within America’s new world order.

One consequence is to vault Canada from seventh to sixth place in the global ranking of arms and military supply exporters. Canada now exports only a few million dollars less in arms than the fifth place arms exporter, China.

Along with American troops, and often other NATO countries, Canadian Forces are on the ground to protect the interests of Canadian investors wanting to invest in the immense wealth of hydrocarbon and mineral resources currently being privatised in Afghanistan and developed elsewhere in the region.

The negative consequence to Canada from this grab for geopolitical power and economic wealth is an incredible cost of legitimacy and international credibility for the margin of independence and legitimacy that Canadian foreign policy once exercised (with recognition of Cuba and a range of older development policies being the most significant examples). Canada is now viewed by many people in the world as an accomplice to American aggression. The mythology of the past that Canadians were peacekeepers was always highly problematic. However, the realisation today that Canada has essentially abandoned peacekeeping and now exercises a most often bellicose and economically opportunistic foreign policy, at the beck-and-call of the U.S., is still jarring for a majority of Canadians. Yet, it is how Canadian foreign policy has evolved over the last two decades with the wider adoption of neoliberal ideology by the Canadian state, the economic integration as a result of NAFTA, and alignment with American geopolitical strategies.

Since its inception, the United States has enacted foreign policy based on a philosophy of revolutionary liberalism. Americans see themselves as inhabiting an exceptional “shining city on the hill.” This gives them the responsibility and thus the right to use warfare to liberalise the rest of the world. Of course there is an immense economic payoff to American investors for their “altruistic” liberalisation mission. This missionary zeal for liberalisation has always been evident in Washington. But it has also infected thinking in Ottawa in recent years in forming both past Liberal and the current Harper Conservative Party governments.

It is useful to look at a key thinker behind the Liberal Party’s foreign policy, Michael Ignatieff, for he frames many of the ways liberals and conservatives, in Canada and outside, have come to identify with the American empire and militarism. In his book, Empire Lite, Michael Ignatieff argues we need to recognise the United States is an empire and that we need to strengthen this empire, so it can be a “humanitarian” empire. Ignatieff uses an argument devised in the 16th century by the Italian philosopher, Machiavelli. His argument claims wars of conquest that use a counterinsurgency strategy such as the current war in Afghanistan and Iraq are inhumane, because, inevitably, such wars cannot be won in the short-term, and thus, will result in long-term suffering.

Ignatieff, like Machiavelli, argues that instead of letting a war drag on over a generation or more, the killing should be done, in Machiavelli’s words, “at a stroke”. A totally devastated state can then be reconstructed rapidly by the victor as the U.S. did in postwar Europe and Japan. This argument for ‘humanitarian’ war is gathering more credibility as the prospects of ‘winning’ the counterinsurgency war against terrorism look further away in the distant future as each day passes.

We might hope that during the current financial crisis, an escalation of the global military strategy might be more restrained because of economic considerations, but history shows examples of wars used to stimulate flailing economies. Growing unemployment could provide the solution to the difficulty of recruiting soldiers in North America. The United States already has bases around the globe and an almost unfathomable arsenal of weapons at its disposal that have yet to be tested in the ‘restrained’ wars the U.S. has fought, since World War II. It is frustrating for some generals to sit on weapons without using them and difficult for manufacturers to justify budgets to build more weapons if existing stockpiles are not used. Since WW II, the United States has never used anymore than a small fraction of the destructive capacity of its arsenal of conventional weapons without even considering the almost unimaginable, but not inconceivable, unleashing of its nuclear arsenal.

The foreign policy Ignatieff advocates in Empire Lite to strengthen the American Empire and remove current democratic restraints that have limited the scale of warfare since WW II could have immense implications in the near future.

With tensions escalating between the United States and Pakistan on the Afghanistan-Pakistan border and aggressive threats made to Iran by the U.S. and Israel, the implications of building an argument to kill a perceived enemy at a stroke is horrific to imagine.

The United States has been fighting a covert war in Pakistan since at least 2004. This war escalated in recent weeks to the point where Pakistani forces allegedly shot at American forces.

Whether Canadian Forces who maintain a long section of the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan participate in the covert war in Pakistan is unknown. Considering Canada’s elite JTF-2 commandoes covertly participated in the initial invasion of Afghanistan, it is conceivable that Canadian Forces could be a part of American covert operations in Pakistan.

During the first U.S. presidential debate, Barack Obama, who is by most accounts the less belligerent of the candidates, stated he would not hesitate to attack Pakistan if provoked. Such an attack on a state possessing nuclear arms would absolutely require the Machiavellian strategy of death at a stroke, rather than the counterinsurgency strategy currently used in the war against terrorism.

Canada and American Aggression toward Iran and Pakistan

What will Canadian politicians order the Canadian Forces to do if the U.S. attacks Iran and/or Pakistan?

The U.S. National Defense Strategy, released in 2008, explicitly outlines a strategy to deal with Russia and China as emerging threats to the United States. At a recent meeting of international relations experts at the University of Toronto’s Munk Centre, Michael Ignatieff described both states as “emerging illiberal empires” whose aspirations need to be contained. The U.S. Defense Strategy advocates engaging Russia and China economically, while forcefully backing this preferred strategy with a secondary strategy of military containment reminiscent of the Cold War.

Canadian politicians have yet to respond to such an explicitly bellicose foreign policy. This is in spite of Canada playing a key role as American ally in fighting a war on China’s border and on the borders of the sphere of influence of both China and Russia?

The National Security Strategy (NSS) of the United States of 2002 and 2006 – the foundational documents of the Bush Doctrine – legitimated the concept of pre-emptive warfare. Canada, almost alone among states, did not formerly protest this radical unilateral amendment to international law.

Often missed within the NSS documentation of the Bush Doctrine is its fourth chapter titled, “Ignite a New Era of Global Economic Growth through Free Markets and Free Trade”. The NSS2002 states:

The concept of “free trade” arose as a moral principle even before it became a pillar of economics. If you can make something that others value, you should be able to sell it to them. If others make something that you value, you should be able to buy it. This is real freedom, the freedom for a person – or a nation – to make a living (NSS 2002, chap. IV).

The Bush Doctrine clearly defines liberal freedoms as dependent upon freedom for capital. Opponents of these “freedoms” are, in the terms of the Bush Doctrine, too easily labelled as terrorists.

While the Bush administration’s term will soon end, its doctrines in the National Security Strategy and the National Defense Strategy are most likely to live on as lasting legacies.

It is startling that the main parties in the Canadian election have barely stopped to ask: what is the global war against terrorism that Canada is a part of really about? Canadians are asked to fight on battlefronts in Afghanistan as well as in the Persian Gulf, the Horn of Africa, Haiti, and elsewhere without a clear idea of what we are fighting for, let alone who we are fighting against.

The leaders of big business in Canada, the United States, and Mexico now advocate even deeper military and economic integration of North America in the proposed Security and Prosperity Partnership (SPP).

We need political leaders who can clearly identify what values are most important to the largest possible consensus of people in Canada and Quebec, rather than merely bow to the wishes of corporate elites. We can remain confident that a majority of people in Canada and Quebec will continue to oppose the war in Afghanistan. They are not prepared to fight a global war led by the United States to expand the freedoms of capital. However, it is not easy to be as confident that any of the leaderships of the major Canadian political parties are prepared to defend the interests of most people against the interests of the leaders of big business and investors in Canada who have tied their interests to American imperial interests.

Either another Conservative or Liberal government, regardless of whether either party form a minority or majority, will continue with the Canadian military intervention. But if the October 14th election produces a coalition of some combination of NDP, Bloc Québécois, and Greens in power, to everyone’s surprise, some opportunities might arise to shift Canadian policy in Afghanistan, the broader Middle East, and our relationship with Russia and China. This would depend upon developing a Canadian foreign policy that is legitimate and in line with the majority consensus of people in Canada and Quebec. An independent Canadian foreign policy would require the assertion of autonomy from the United States, and confront the way the imperial interests of Canadian business and elites have allied with the Bush Doctrines and American imperialism.

Whatever the outcome of the election there is little reason to be hopeful that an independent, equitable and legitimate foreign policy might emerge spontaneously. Developing such a foreign policy will, in fact, depend upon the peace movement and many of the other critical campaigns against the current imperial policy continuing to grow and converge. These movements must penetrate into key sectors such as the union movement and partisan politics. This will remain a crucial political task for the left after the election, with the demonstrations against the war on October 18 being another step in that direction. •