Out of Sight – Out of Mind

Toronto’s ‘Streets to Homes’ Response to Homelessness

The City of Toronto’s ‘Streets to Homes’ program is a finalist for one of two awards that will be presented during the celebration of United Nations’ World Habitat Day. These annual awards are given for “practical and innovative solutions to current housing needs and problems.” ‘Streets to Homes’ is an initiative that focuses on placing people who are on the streets in housing units, and is presented as a bold and vital step that can actually eliminate the destitution of poverty in Toronto.

“Streets to Homes is helping us to end street homelessness,” Toronto Mayor David Miller has claimed. “It is making Toronto a more inclusive city, and the world is taking notice. This recognition is a tribute to both City staff and our community partners, who have worked together tirelessly and seamlessly to help some of our most vulnerable citizens.”

As I write this article, the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty is preparing to take a delegation to the office of the Coroner of Ontario to challenge the death of yet another person whose homelessness had been ‘solved’ by ‘Streets to Homes.’ He was dumped in substandard accommodation in an outlying part of the city without the supports that would enable him to survive. He perished in that setting.

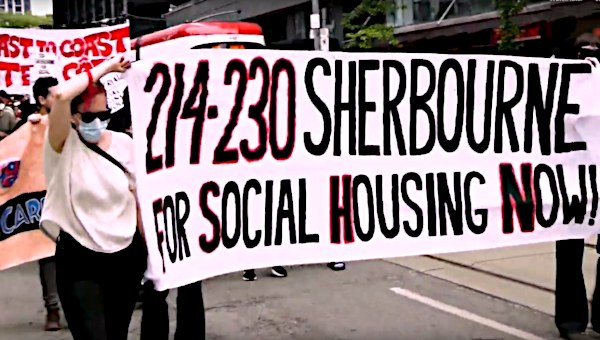

There is a glaring contradiction between the ‘Streets to Homes’ initiative as it is presented by its boosters in Toronto City Hall and the quiet, hidden misery that plays out in the lives its ‘success stories.’ Even viewed, simply and immediately, as a program that has put some 1,500 homeless people into housing units over three years, there is much that is flawed and even shameful about ‘Streets to Homes.’ However, the bigger question and the greater outrage lies in its role in both concealing and serving an agenda of driving the poor and homeless from the centre of the city in the interests of redevelopment. Before we can grasp the significance of ‘Streets to Homes,’ we must first look at the essential nature of this process and the ways in which it is being pushed forward.

Urban Redevelopment and the Poor

Redevelopment in Toronto is proceeding under conditions where the scale and depths of poverty have already been increased by declines in real wages and the removal of important elements of social provision. Unemployment insurance has been gutted, social assistance rates slashed and the governmental initiatives that once generated housing for low income people have been scrapped. Some 70,000 people sit on waiting lists for social housing in this city, while the housing stock they wait to occupy crumbles for lack of basic upkeep.

It is under these regressive conditions that poor communities find themselves targeted by upscale redevelopment. Decades ago, developers focused on generating suburban sprawl but the driving down of property values in the central area that this facilitated, created, over time, a reverse process. Since these are market forces and not rational planning, this process has turned into a frenzied drive to create an oversupply of upscale housing.

The developers’ appetite for profits may be unlimited but urban space is decidedly finite. Much of the territory slated for redevelopment is already spoken for. Poor people have created homes and neighbourhoods. Public housing projects have been constructed. People marginalized by deindustrialization and social cutbacks have moved into the city centre where they stand the greatest chance of surviving. These low income populations are, therefore, in the way and, as peasants were once driven out to make room for sheep grazing, so poor and homeless people are today removed to provide space for luxury condos.

Middle class professionals moving into these contested areas are not comfortable with the evidence of social destitution around them. The merchants who cater to the new occupants want to be free of the homeless. The logic of investment, property values and ‘quality of life’ demands they be removed. An unholy alliance of business interests, higher income residents, media, cops and politicians is formed to take on this job. Since it is the municipal level of government that has been developed to carry out the public functions that are most closely related to the needs of property investment, City Hall has a central role to play in this regard.

Toronto City Council and the

Urban Clearing of the Poor

We can only be struck by the fact that this process of social exclusion reaches its peak when a majority of the seats on Toronto City Council are occupied by those who have long been viewed as its ‘progressive’ wing. Sadly, however, David Miller and his closest collaborators on Council are organizing to further the clearing out of the poor and homeless with an effectiveness that greatly outdoes the halting efforts of the last Mayor.

Miller is able to put a gloss of social enlightenment on the ugliest acts of social injustice. He looks pained when intolerant people talk about the homeless in mean spirited terms. To him, they are ‘some of our most vulnerable citizens’ who need to be cured of their ‘street homelessness’ by way of the ‘tireless’ and ‘seamless’ work of ‘Streets to Homes.’ This is a telling starting point. The issue is not the economic and political decisions that have led to poverty and hardship. It is the ‘illness’ of ‘street homelessness’ that must be tackled and that only requires that the homeless not be on the street or, more exactly, that that not be seen by those with money and influence who don’t want them there. If their removal from the scene can be organized in a way that appears decent and caring, so much the better, but that is a secondary matter. The key concern is to get rid of visible homelessness. It this regard, ‘Streets to Homes’ is a dubious velvet glove in a very iron fisted operation.

The most direct method of discouraging homeless people from staying around is, of course, to set the cops on them. However, City Council tells us that it is not in favour of the ‘enforcement option’. It has developed caring approaches to ‘street homelessness’ and panhandling that will work much better. These claims notwithstanding, it is important to note that the institutions directly under the control of the City are, in fact, heavily involved in the ‘enforcement option’. City bylaw officers go after poor street venders and homeless people looking for places of shelter all the time. The City has even made clear that it will now target the people who collect up empty bottles and cans for the deposit money on the grounds that such items have been left out for collection by the City and these ‘scavengers’ are taking municipal property.

When it comes to the Toronto Police, however, we are witnessing a massive, unrelenting and escalating drive to force out homeless people. Tickets are being given out to panhandlers under the Safe Streets Act in hugely increased numbers and people are going to prison under this legislation. It is supposed to be legal to panhandle but it has become routine to give out ‘aggressive panhandling’ tickets to people sitting quietly on the sidewalk. The OCAP office has even dealt with homeless people who have been given Safe Streets tickets when they weren’t panhandling. It may be true that these cops don’t act under the direct instructions of City Council but it is the members of that body who have chosen to increase the police budget to over $800-million and it is David Miller who boasts that there are more cops on the streets than ever before. These additional cops will, as a matter of course, persecute the homeless on behalf of the Business Improvement Associations.

Streets to Homes or to Slums?

When we draw up a balance sheet for ‘Streets to Homes,’ it is important to consider that the resources for this initiative have been found by changing priorities and by withholding funding for long standing and vital services for the homeless. Despite the official line from City Hall officials that there are enough beds within the homeless shelter system, people are being turned away from these places every night. Five shelters in the central area have been closed with only inadequate replacement of the lost beds. This also translates into a loss of 340,000 meals for people on the streets. These cuts mean worse overcrowding, violence and illness. The strategy is to remove the services people need when they are homeless, to cut back on things like street patrols, drop-ins and emergency shelter and, then, to simply repeat that ‘Streets to Homes’ is working and homelessness is going away.

In its day to day operations, ‘Streets to Homes’ plays a very significant and direct role in this process of removal. One study based on the program’s own figures, showed that 36% of housing placements were in outlying parts of the City. This, however, massively understates things, since the statistics that were released defined the central area as the pre-amalgamation City of Toronto and East York. This would mean that a chunk of those who were not moved, literally, to the suburbs would nonetheless be placed in neighbourhoods a very considerable distance from the support networks and services that had enabled them to survive in the past. Certainly, it appears that a majority of people being placed in units by ‘Streets to Homes’ are being dumped outside of the gentrifying and contested areas they were unwelcome in.

The people that OCAP has contact with confirm this notion of a reckless process of removal that pays scant attention to the needs of those exiled to suburban poverty and isolation. We talk to people who have no food and no way of accessing it and who find their way back downtown in an effort to survive. We talk to others who have been placed in tiny, scantily furnished apartments in neighbourhoods where they know no one, without access to public transport or any conceivable form of recreation and who sink into a lonely and depressed state.

The housing conditions that are being experienced have given rise to an unofficial name for the program of ‘Streets to Slums.’ We have seen people living in conditions that would not be tolerated in a jail or homeless shelter. To drop people without income into deplorable housing and provide them with no real support is a recipe for despair and tragedy. Despite the huge waiting list for public housing in Toronto, people are even being put into Toronto Community Housing under ‘Streets to Homes.’ The rule is that, if a public housing unit is refused three times, it can be allocated to someone through ‘Streets to Homes.’ For a place to be rejected several times by people who have waited years for rent geared to income housing, you can be sure it is in shameful condition. Yet each human being warehoused in places desperate applicants have rejected is held up before the City and, now, the world as another admirable statistic, another ‘success.’

Toronto’s Urban Policies:

Serving Redevelopment Not the Poor

The great shame of the ‘progressive’ majority on Toronto City Council is that they have accepted, with their ‘Streets to Homes’ initiative, the agenda of the capitalist classes for redevelopment as an inevitability to which they must submit. It’s quite true that the higher levels of government carry most of the blame for the gutting of social provision and the proliferation of poverty and destitution. That, however, does not excuse Toronto’s present course. Year by year, the Police budget becomes more and more bloated while public housing falls apart.

That the Province has abandoned this housing stock is true but why should it be more of a priority to unleash record numbers of cops on poor communities than to divert resources in order to maintain public housing stock? Indeed, the City has brokered arrangements under which thousands of units of Toronto Community Housing are being demolished to build ‘mixed neighbourhoods’ Regent Park is being recreated as a condo development with, supposedly, a portion of the housing reserved for rent geared to income residents. Even as Phase One of the development goes up, the actual number of public housing spaces has been reduced and no one in touch with reality could imagine that this is anything other than a process of destroying public housing. That such a course will fuel homeless is painfully obvious.

Lack of decent income is the greatest factor in putting people on the streets. Record numbers of economic evictions are taking place and appallingly low social assistance rates are the key reason for this. True, City Council has passed resolutions that call on Queen’s Park to restore welfare rates to the real level they stood at before Mike Harris took power. However, such gestures count for very little when municipally run welfare offices operate on the basis of denying benefits whenever they can. If the City were to adopt a policy of full entitlement and ensure that people were told of all available benefits and granted them to the greatest extent possible, economic evictions would decline significantly in Toronto. Yet, City Council has approved measures of welfare ‘case management’ that will ensure that people in need will get as little as possible.

‘Streets to Homes’ is another component of this general political direction. Those driving redevelopment want the contested areas of the City cleared of the homeless and models of ‘solving’ the homeless crisis and ‘rehabilitating’ those who have fallen into ‘street homelessness’ have been thoroughly developed in the major U.S. cities. This is now adapted for use in Toronto and given a name that conjures images of reclaimed lives. The ugly truth is that resources that could actually deal with homelessness are serving the needs of redevelopment. To the extent that it is possible, the homeless are to be pushed out. Some will be driven off by police intimidation. Some will find the shelters and services they need no longer available and leave in despair. Some will be dumped in outlying areas without support in places that have four walls and a ceiling but make a mockery of the word ‘home.’

‘Streets to Homes’ is dishonest to the core. It deserves to be exposed and challenged, not handed awards. In place of an inhuman agenda that drives the homeless from view, we need the solutions to homelessness that will come, not from adapting to upscale redevelopment, but from mobilizing communities to fight it. •

Resources:

- Raise the Rates: The Vital Struggle Against Ontario’s Sub-Poverty Welfare System by John Clarke

- ‘Poverty Reduction’? Reforming without Reforms in a Neoliberal World by John Clarke

- Importing Blair’s Failure: Ontario’s Poverty Reduction Strategy by Bryan Evans

- Treading Water: Four Years of Ontario’s Liberals by Bryan Evans