Canadian Workers Demand Immediate End to War in Afghanistan

On 29 May 2008, the delegates at the national convention of the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC), representing more than three million workers from every region of Canada and Quebec, voted overwhelmingly to demand that the Government of Canada immediately end its participation in the illegal war in Afghanistan.

This CLC demand represents a significant consolidation of labour power. Several national unions, notably the Canadian Union of Postal Workers (CUPW) and the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) had already adopted policies to oppose Canada’s participation in the war in Afghanistan. However, some powerful unions whose members work in the rapidly expanding Canadian military and development industries could profit from continuing the war. The women and men of these unions made the difficult decision to stand in solidarity with the working people of Afghanistan rather than act on self-interest.

The Afghan War and the Canadian Military

The ongoing war in Afghanistan continues to kill uncounted thousands of Afghan civilians and cause immeasurable suffering due to horrendous injuries, the displacement of people from their homes and livelihoods, home invasions, arbitrary arrests and torture, sexual abuse, and the general humiliation of Afghans. This is an illegal war that cannot be justified by a few extra jobs for Canadian workers.

Since the war in Afghanistan began, Canada has become the sixth largest military exporter in the world, according to data collected by the U.S. Congressional Research Service. Canada is now behind only the USA, Russia, the UK, Germany, and China in export volume. The U.S. manufactures more than all other military manufacturers combined, so comparing Canada’s military industrial complex to the American mega-industry is ridiculous. But, Canada trails China – number five on the list – by only a hundred million dollars worth of exports in an industry that brings billions of dollars into Canada. No one knows exactly how many billions of dollars military exports bring into Canada though. Why not? Because, for the past four years, the Canadian government, citing security concerns, has refused to release much of the data regarding the export of military products to the U.S. – our biggest customer.

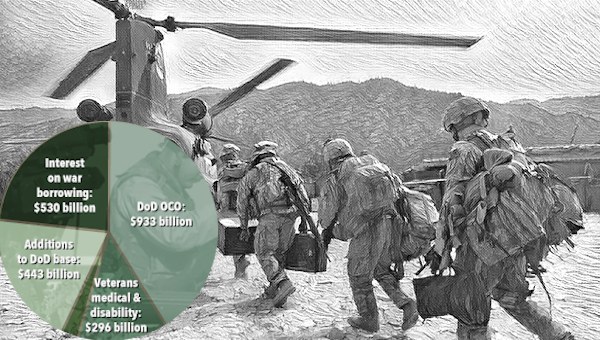

Canada’s own military spending has risen considerably. Since the war began in 2001, Canada rose from the position of 16th to 13th biggest military spender in the world, and from 7th to 6th within NATO, according to a Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives report. Canada’s defence budget projects a 37 percent increase in spending from 2001 to 2010.

The Canadian Association of Defence and Security Industries (CADSI) represents more than five hundred companies. In an interview with a CBC journalist, the CADSI president, Tim Page, claimed his industry represents about 70,000 jobs in over 177 federal ridings. This may not seem like a large number of workers, but it represents significant political power. Many of these high-tech jobs are among the best in the country.

However, the workers who build the weapons and everything else needed for warfare, as well as the service workers who make the Canadian state function, recognise that it is the shareholders who profit most from the rising fortunes of the companies in Canada’s military industrial complex. Corporations such as GM Canada, Bombardier, Bell Helicopter, SNC-Lavalin, CAE Electronics, Pratt & Whitney Canada, Canadian Marconi, and Colt Canada are only a few of the Canadian based military suppliers profiting from the war in Afghanistan.

Canadian Development Aid in Afghanistan

The Canadian development industry also profits from the war and occupation. The one billion dollars Canada has “pledged” to spend on development in Afghanistan, from 2001 to 2011, pales in comparison to the 7.2 billion dollars already spent on the military mission. Nonetheless, a billion dollars is a significant sum. However, most development spending returns to Canada as salaries and expenses. Manufacturers as well as service providers such as construction contractors and airlines profit significantly from the development industry – while the little development spending that actually does reach Afghanistan benefits few Afghans.

When our research group toured five Afghan provinces in 2007, we were appalled by the miserable conditions most Afghans must live in. Even in the safest areas of the country, where there is no excuse for the occupying forces failure to reconstruct essential infrastructure, many Afghans do not have even the barest essentials of clean water and adequate sanitation. In Kabul, where the international forces have occupied the city since 2001, less than 29 percent of the people have access to clean drinking water, according to reports by the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit.

Peter McKay, Canada’s Minister of Defence, frequently claims that over six million Afghan children – one third of them girls – have been enrolled in school. However, his claim is not substantiated by Afghan researchers. Girls represent only 3 percent of students, according to the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission. The children of poor families cannot afford school; they must work to survive. The Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit claims this fact especially inhibits girls from going to school.

When we interviewed people in Afghanistan, their experiences of development sounded very much like what Michael Ignatieff had described in his book Empire Lite in 2003. Ignatieff stated:

The rhetoric about helping Afghanistan stand on its own two feet does not square with the hard interest that each Western government has in financing, not the Afghans, but its own national relief organisations. …These fly a nation’s flag over some road or school that a politician back home can take credit for. … the international’s first priority is building their own capacity – increasing their budgets and giving themselves good jobs (Michael Ignatieff. Empire Lite. 2003).

Since becoming a politician, Ignatieff no longer talks about these issues, but Afghans see this reality every day.

Commercial Exploitation

Despite the fact there is no systemic development of the basic infrastructure necessary for human survival in Afghanistan, massive commercial developments proceed at a rapid pace.

The biggest development to date is the Aynak copper mine just a few kilometres from Kabul. This rich mine site was auctioned, in late 2007, to the Chinese metallurgical corporation MCC for a price of more than 3 billion American dollars. The Aynak deposit is the first of more than 1,400 state owned mineral deposits in Afghanistan slated for privatisation in the near future.

A Soviet geological survey in the 1970s found – and American and British surveys since 2001 have confirmed – massive deposits of almost every kind of mineral wealth exist in Afghanistan, such as gold, iron, uranium, and copper, as well as hydrocarbons, especially coal. Afghanistan is also one of few locations on Earth where the rare element tantalum, also known as coltan, is found. Tantalum is essential in the manufacture of cell phones and laptop computers. The largest previously known source is in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where tantalum mining played a part in the most destructive war, in terms of human casualties, since WWII.

Canadian mining giants are competing with American, British, Russian, and Chinese companies in a scramble for the rich mineral prizes found in Afghanistan. Financial predictions for the Afghan mining industry are in the unfathomable hundreds of billions to trillions of dollars. But, as an article by Antony Benham in the October 2007 issue of “Nature” notes, it is unlikely much of this wealth will benefit many Afghans.

Development of the transportation and energy infrastructure needed by the mining industry is rapidly proceeding, while ordinary Afghans suffer without the most basic necessities of life. Some sceptics claim that even the electricity to be transported by a transmission network currently under construction funded by the Asian Development Bank, is not likely destined for the millions of Afghans without electricity, but will instead be sucked up by electricity hungry ore processing plants.

Whether it is here in Canada, in Latin America, in Africa, throughout Asia, as it is now in Afghanistan, the Aboriginal Peoples who live on the land are perceived to stand in the way of what we in the so-called developed world call development. The environmental devastation that can be caused by resource extraction is well known, but this is a fact known better by those people directly affected who rely on their land for their livelihood than by anyone else. However, the disciplinary power of the modern state is being used to counter any protest, eliminate all resistance, and clear the land of Aboriginal Peoples wherever it is deemed necessary.

The New Afghan Theocratic State

The destruction of the Taliban regime by American armed forces in 2001 effectively silenced opposition and effectively re-instituted a theocratic regime. A theocratic state was first imposed on Afghans in 1992 when the U.S. helped the mujaheddin gain power by financing their war with billions of dollars against the secular Soviet-backed government. American President Jimmy Carter initially began providing military and other support for the mujaheddin Islamic revolutionaries on 3 July 1979, which then drew the Soviet military into Afghanistan 25 December 1979. In coming to power, the mujaheddin declared Afghanistan an Islamic republic. The ouster of the mujaheddin by the Taliban in 1996 brought an even greater degree of social and political repression for Afghans, and intensified the theocratic features of the Afghanistan state, often through brutal means.

Secular Afghans, those of other faiths, and Muslims who believe in a separation of state and religion have been profoundly disenfranchised by the theocratic state that first gained support from the Western powers in the 1990s. They have remained so by the new theocratic state re-established, under the puppet leadership of President Karzai, by a handful of Western leaders in the Bonn Agreement of 2001. The Bonn Agreement was instituted despite a UN Security Council recommendation issued several weeks earlier that urged that “the new Afghan government should respect the human rights of all Afghan people, regardless of gender, ethnicity or religion.”

The Bonn Agreement accomplished, among others, three objectives with profoundly adverse consequences for many Afghans. First, it rewarded the mujaheddin warlords for their decades of services to the USA. Second, it promised the mujaheddin impunity for the many horrendous war crimes they had committed since 1979, which continue to this day during the American-led occupation. Third, it re-instituted the theocratic state as a means of social control.

The U.S. State Department reports: “The government requires all citizens to profess a religious affiliation and assumes all Afghans to be Muslim. According to Islamic law, conversion from Islam is punishable by death.” The U.S. State Department also reports that socialism is illegal in the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, because socialists are atheists.

Afghan political opponents of many progressive stripes must remain underground fearing retribution from both the Taliban insurgents and the ruling mujaheddin regime. In essence, the only substantive difference between the Taliban and mujaheddin regimes is that one is an intolerant authoritarian theocratic regime bent on resistance to the new world order and the other is an intolerant authoritarian theocratic regime willing and well prepared to profit from engagement with the new world order.

Now that the workers of Canada and Quebec have officially declared our solidarity with Afghan workers, it is time to begin building bridges to join our struggles against the new authoritarianism and theocracy in Afghanistan and Western and Canadian imperialism. •

In 2007, Skinner and Afghan-Canadian researcher Hamayon Rastgar, representing the Afghanistan Canada Research Group, travelled throughout much of Afghanistan. They listened to Afghan intellectuals, opposition politicians, and particularly the ordinary Afghan workers and peasant farmers whose views are not represented in the Canadian media (read dispatches on TUAW website). You can see a short video of this research, “Searching for Development in Afghanistan.”