The Crisis in Manufacturing Jobs: Struggling for Answers

- Manufacturing in the Canadian Economy

- Should We Give Up On Manufacturing Jobs?

- An Alternative Program

- Rethinking Unions

- Community Responses: The Example of Windsor

The last weeks of May have seen major demonstrations of workers’ discontent with the crisis that has been unfolding in Canada’s manufacturing sector. Some 52,000 jobs have been lost in the manufacturing sector since January alone. The demonstrations were kicked off on May 23 by protests by the USW at nine plants, as part of its ‘Jobs Worth Fighting For’ campaign linked to the Ontario Federation of Labour. The USW actions included plant occupations, notably at doormaker Masonite, which is shutting down its Mississauga plant to move its production to U.S. facilities with the loss of 300 jobs.

In Windsor nearly 40,000 turned out on May 27 from unions and the wider community to protest the loss of manufacturing jobs and the economic crisis that has been besetting Windsor. The demonstration was led by the CAW locals, but also included support from other unions, such as CUPE, the teachers’ unions, and the Chatham-Kent District Labour Council. The demonstrators marched from several Windsor streets and converged at the Ford Test Track. Remarkably, the demonstration was larger than the October 17, 1997 Days of Action area general strike against the neoliberal policies of the then provincial government of Mike Harris. The demonstration was followed by another in Oshawa the same day by General Motors workers and the local community.

And on May 30th, the Canadian Labour Congress and affiliated unions brought several thousand angry workers out to Parliament Hill as part of their ‘Made in Canada Jobs’ campaign. The CLC-led demonstration focused on the impacts of the high Canadian dollar – now at about 93 cents to the U.S. dollar – and the impact of NAFTA and proposed trade deals with countries like South Korea.

Up to this point, there has been a near complete absence of either union or political action. What has unfolded is predominantly a series of union concessions, government subsidies, calls for opening East Asian markets for North American exports and demands for improved severance for laid-off workers. Both the provincial and federal governments have almost completely withdrawn from active industrial policies. They have focused on cutting wage, social and tax costs for capital, even further accelerating the rate of tax write-offs for new capital investment and expanding free trade agreements, including the project of deep integration with the USA.

It is clear that the crisis in the Canadian manufacturing sector is intertwined with the larger neoliberal policies that have come to dominate politics and the impasse of the union and socialist movements. The protests by workers over the past weeks illustrate well the deep-seated frustrations. And they allow for wider debate about the campaigns and politics that will need to develop. These are, in our view, quite dependent on a sustained period of union renewal and the formation of new organizational and political capacities within the socialist movement.

The Canadian Labour Congress (CLC), spurred on by initiatives from the Canadian Auto Workers (CAW), United Steelworkers (USW) and Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union of Canada (CEP), has moved to place Canada’s devastating loss of manufacturing jobs on the national agenda. This initiative is significant for a number of reasons.

- To begin with, it asserts that the problem manufacturing workers face is more than cyclical; the problem will remain even if the economy ‘strengthens’.

- In addition, the campaign extends to all of manufacturing, not just any particular sector, and so holds out the prospect – already too-long delayed – of building bridges across unions.

- And by looking to build strength in the community as well as the workplace, the campaign addresses a crucial mobilizing space which unions have so far not sufficiently or adequately addressed.

Judging from the CAW, where the campaign has, by spring 2007, been more developed, the enthusiastic membership response seems to have breathed some new life and hope into the union. It is clear that a good many local leaders, disheartened with the never-ending demands of concessions and frustrated with waiting for the next corporate threat or devastating announcement, have been anxious for such fightback campaigns.

But will the campaigns deliver? The most recent attacks on jobs and working conditions are not new; corporations and governments have, over the past three decades, radically stepped up their aggressiveness. Yet, no counter-response has to date emerged from Canadian unions to match that corporate radicalism. If we do not convincingly show that we are not going to keep taking this; if we do not lead a fundamental challenge to how the potential of our country is used; if we do not build a campaign broad enough and powerful enough to actually compel Canada’s corporate and political elites into making concessions to us – then we should not be surprised that tomorrow offers only more of the same.

The issue of jobs, as well as the more general issue of what is happening to working people, will not be reversed without a much deeper rethink of the labour movement’s vision and direction, structures and strategies. This pamphlet tries to contribute to that missing discussion. It begins with some background to the very useful information unions have been disseminating [see the web-sites of the respective unions]. We then turn to a discussion of alternatives. Ultimately, however, we have to supplement any alternative policies with an alternative politics – a new way of ‘doing’ that builds our collective capacity to understand, strategize, and act to place new options on the national agenda. Amongst other things, this will mean reinventing our unions.

Manufacturing in the Canadian Economy

1. The loss of manufacturing jobs is not just a Canadian problem.

Over the last quarter century, capitalist development has meant a general shift from manufacturing jobs to service sector jobs. The actual number of manufacturing jobs fell in virtually every developed country – by 11% in Germany, 15% in Japan, 25% in the U.S. and almost 50% in the UK. The one exception to this trend was actually Canada – though the increase in Canadian manufacturing jobs was very small (under 2%) and over the past few years it too has, as Canadian unions have emphasized, been falling dramatically.

| Manufacturing Jobs Developed Capitalist Countries |

|

|---|---|

| Change 1980–2006 | |

| CANADA | 2% |

| GERMANY | -11% |

| ITALY | -11% |

| AUSTRALIA | -13% |

| JAPAN | -15% |

| USA | -25% |

| FRANCE | -31% |

| SWEDEN | -36% |

| UK | -47% |

2. The manufacturing job loss is about more than trade.

Trade is obviously a factor in the job loss. Over the last thirty years but especially since the early 1990s, the developing world – which was previously relegated to providing resources to the developed capitalist countries – has come to include a few large countries that are major manufacturers. The impact of this on our jobs should, however, not be exaggerated. About 85% of our imports still come from the developed countries rather than the developing ones. And in the crucial auto industry, the job loss is, increasingly, not a result of imports but the loss of market to companies like Toyota and Honda with factories increasingly located here. (This should, of course, not obscure the intensification of corporate attacks on workers’ wages and conditions as international competition grows and corporate options spread).

3. More goods are being produced with fewer workers.

The fact is that the real value of good produced in Canada – output in manufacturing adjusted to exclude the effect of inflation – is about double what it was a quarter century ago (this is also true in the USA). But the rapid growth in productivity per worker (more technology, the restructuring of work, the old-fashioned but more sophisticated pressures for speed-up, and, to some extent, longer hours) has led to an increase in production without a corresponding growth in the number of workers.

China is the most stunning example of this effect of productivity and restructuring. In spite of its remarkable rise as a global manufacturer, the number of manufacturing jobs in China has actually fallen by some 15 million over the past decade – more than the sum of manufacturing jobs lost by all the developed capitalist countries combined! The explanation for this apparent paradox lies in China’s shutting down of tens of thousands of small manufacturing plants in rural areas (the legacy of Mao’s emphasis on local self-sufficiency) and concentrating them in larger, more ‘efficient’ operations. As well, China has privatized and ‘rationalized’ its former publicly-owned operations.

Should We Give Up On Manufacturing Jobs?

Of course not – the very fact that manufacturing jobs are scarcer than ever makes it all the more important to fight to keep what we still have. Manufacturing is so important in part because manufacturing jobs remain the best-paying jobs. As well, though only one Canadian job in seven is now in manufacturing, if we include manufacturing’s spin-off jobs, the impact on the larger economy is much higher. And retaining a manufacturing capacity – the skills and knowledge to make things we need – is fundamental to also building any alternative society.

At the same time, we should not have any illusions about ‘high tech’ manufacturing necessarily implying more manufacturing jobs overall – as vital as this is to future productive capacities. The U.S. is the world’s foremost high-tech producer, yet the share of manufacturing jobs in total jobs is even lower in the U.S. than it is in Canada (11.8% in the U.S. versus 14.4% in Canada) – and the pressures there on the working class are even harsher than what workers face in Canada.

The on-going restructuring of industry means, moreover, that even when the total number of manufacturing jobs is not falling, individual jobs are still shifting from plant to plant, company to company, across sectors and across regions. It does not mean very much to tell a 50-year old steelworker in Hamilton that he may have lost his job but that Honda is hiring young workers in Alliston, or that a computer chip factory outside of Ottawa is looking for engineers, or that the Quebec aerospace industry is expanding.

The reality we confront is that:

- Most of the manufacturing jobs that were lost aren’t coming back;

- Many current manufacturing workers will in the future be forced out of manufacturing into other sectors;

- Even within manufacturing, its ‘elite’ status relative to other sectors is under attack.

The above points raise three sets of questions that have profound and inter-related implications for what manufacturing unions do and how they do it. They are worth summarizing before we turn to alternatives.

1. What kind of society do we want?

In defending ourselves we have traditionally focussed on protecting or expanding the existing structure of production. But when we look to the future, it is clear that demanding more of the same is not good enough, and not really desirable. We need to keep raising a prior and more basic question: What kind of society do we want and what does this imply for the kind of jobs we could and should be struggling to create?

2. Can we win if the working class remains so fragmented?

Unions are oriented to raising the standards of a particular group of workers. At best, this tended to ratchet up the standards of others. This seemed to work for a while, but it now dangerously isolates workers who did earlier move ahead. And it offers no long-term protection for the growing ranks of former manufacturing workers who have been ‘dislocated’ and have now moved into non-union service sector jobs or become unemployed. Stopping the decline in unionization is one answer, but it is not enough. Solidarity in raising the standards of all working people through the ‘social wage’ as expressed in universal health care, decent pensions, unemployment insurance, higher minimum wages and welfare rates, is increasingly the key to even hanging on to past gains. In self-defence as well as in the name of solidarity, the old strategy of moving ahead in the unionized sector and hoping this will set standards for others will have to give way to a new emphasis on setting standards with and alongside the rest of the working class in unorganized and precarious sectors of work and also those without work.

3. Are community struggles an add-on or fundamental to class struggles?

Unions have never ignored the community, but the site of struggle for unions has primarily been the workplace. This will always remain central to introducing workers to, and developing their confidence in, the possibilities of collective action. Yet, if working people are more than ‘just workers’ and have broader community and cultural interests, doesn’t strengthening the relationship between the union and its members require substantially expanding the representation of workers’ needs in the community? Is this not especially important as plants close and union members no longer have jobs – but remain in the community? And is this not all the more crucial as the extent of what we are up against demands a greater reliance on community allies?

It is clear there are no easy and comfortable solutions to what we face. But if the problems we face are large, we also have to consider bolder solutions, and ones that do not just cater to the corporations. A common contradiction is identifying the corporations as the source of our problems – and then putting forth ‘solutions’ that strengthen those same corporations and end up weakening unions and workers.

An Alternative Program

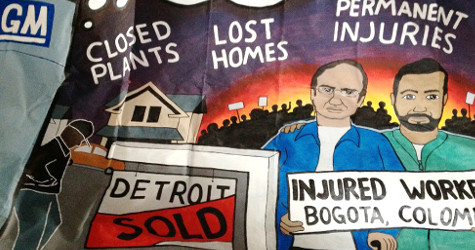

1. Fighting Plant Closures.

In a society based on competition and the unilateral right of corporations to do what is best for them, plant closures are ‘natural’. Our role, however, must be to challenge the legitimacy of actions which, in

taking away the tools and equipment we need, robs us of our productive potential and ability to meet our needs. Direct resistance in the form of plant takeovers – as both the CAW and USW have recently done – must become more common (even ‘natural’) if we expect politicians to take the loss of manufacturing jobs seriously.

Yet, even when workers do take plants over, they are usually limited to using it as a bargaining chip to defend or improve benefits. As important as this defensive measure is, we also need to develop a capacity to keep these plants in operation, including the capacity to convert them to some of the many products we currently import, or do not produce enough of, or those products we might need as environmental restructuring and other social changes occur.

2. Reducing Work-Time.

The essence of unionism is negotiating the price and conditions of labour rather than the creation of the jobs themselves. But sharing existing work through reducing the hours of full-time workers has been a traditional union focus for the opening up of full-time jobs. It is rather ironic that with all the recent advances in technology and productivity, and with more family members in the workforce, hours of work for full-time workers have gone up rather than down and the issue of reduced work-time has largely faded from the agenda – except where it serves the corporate purposes of flexibility and the lower earnings and benefits of part-time work.

Reduced work-time is about more than new openings for some and leisure for others. It is also a condition for the mobilization needed to affect change; workers drained by overtime confront additional barriers to genuine participation. This concern was at the core of building the Canadian labour movement in the latter part of the 19th century. It can now contribute again to labour’s revival.

3. Developing Sectoral Strategies.

We can not solve the jobs issue by addressing closures one at a time. We also need to develop longer term strategies for each sector. This might start with some of the proposals from earlier ‘industrial strategies’, such as a continental autopact to regulate the corporate commitment to jobs in each of Canada, the USA and Mexico; a return to public ownership in aerospace; up-stream processing of resources in Northern mining communities and in the forestry sector; committing the billions governments spend on goods – from hospitals to furniture and office supplies – to greater local purchasing. But we also need forward looking strategies that reform public and industry planning capacities; establish public ownership, and end corporate subsidies without adding to public control; push ahead innovation capacities in key sectors of new value-added; and that guide the production of use-values for human needs – such as in housing, libraries, healthcare, parks and recreational facilities, public transport – apart from market criteria. All the planning for future production now takes place only in corporate bureaucracies, and not even in governments, and certainly not with the objective of developing workers’ control and input into production.

4. Incorporating ecological concerns and responsible production.

Yet, as noted above, we will also have to take on creatively transforming what we do, not just defending what we did. This is where the ecological crisis comes in.

Responding to environmental concerns will be a dominant issue for the rest of this century. This goes beyond tighter standards in particular sectors; everything will change. Cities and transportation will be transformed, as will how our homes are heated and what kind of appliances we use. Some industries will fade while others will expand and new ones will emerge. For all the concerns about the environment threatening manufacturing jobs, all kinds of new products will be demanded by environmental-driven change – wind turbines and blades, solar panels, public transit equipment, new vehicle engines, reconfigured appliances, anti-pollution factory equipment, energy-saving motors and machinery, new materials for homes and offices. A serious job strategy would have to develop the capacities to provide these new products in an effort to move toward more ecologically-responsible production. And in such planning, we should not wait to see if Canada’s private sector will find this direction profitable. The need is clear, we have the potential to address it, and governments should directly create the public companies to bring those needs and potential together.

5. Linking Manufacturing and the Public Sector.

In the public sector, resisting privatization is not only a matter of job security and standards, but also a matter of confirming the advantages of goods and services provided on the basis of need, not profit (in terms of quality, value, access, and commitment to stay here). A credible public sector represents, therefore, both an ideological challenge to corporate ‘logic’ and a vehicle for addressing manufacturing jobs in a way quite distinct from the dominant bias in favour of private ownership to develop the Canadian economy. Canada’s aerospace industry, for example, was developed and sustained through public ownership in the critical years when the private sector refused to do so.

But it is ultimately self-defeating to automatically define the public sector in itself as ‘good’. Given the power of business and the dominance of capitalist values in our society, the public sector faces great pressure to become more commercialized and to operate, even without privatization, on private-sector lines. Unions must therefore lead the struggle for a particular kind of public sector. Working towards this would mean public sector workers identifying their most important allies as often also being their clients – as the Public Service Alliance (PSAC) did when some time ago it prepared pamphlets for the unemployed on receiving their rights when dealing with the government, or when the Canadian Union of Postal Workers (CUPW) offered to deliver cheques to retirees during a strike against the post-office, or when Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) Hydro workers led the campaign against privatization of our electricity). More generally, it means public sector workers and unions fighting for a greater responsibility in the management of a public sector that could establish itself as a more democratic and effective alternative to corporate control.

6. Linking Workers and Unions with Community Strategies.

The issue of economic development has a regional as well as sectoral dimension. The focus in each community will differ – the response in Toronto will differ from that necessary in southern Ontario auto towns or in northern Ontario in mining or forestry communities. However, two common issues that would have to be taken on are: What kind of structure might effectively address the issue of manufacturing jobs or jobs to replace manufacturing? How will this be financed?

(a) Job Development Boards

The creation of local Job Development Boards would introduce a community planning capacity and guarantee (much as the right to basic schooling is now a taken-for-granted right) decent jobs for anyone willing to work, or the training leading to future work. These boards would include a research and engineering capacity and an educational component on economic literacy so people could more comfortably participate in the discussions. It would survey the community to establish needs and productive capacities; hold public forums to prioritize ideas and proposals; engage the community in discussions on local needs and possibilities; block corporate attempts to remove plant and equipment from the community and prepare conversion plans for the production of new goods; and develop plans to upgrade the community’s economic and social infrastructure (transportation, clean water, sewage, environmental clean–up, schools, child care, services for the aged sports and culture) – much of which would also require local materials and equipment.

(b) Financing

If the federal government could so easily find the funds to send Canadian troops to support the American invasion of Afghanistan, why couldn’t it find funds for socially useful projects at home? If governments can readily provide subsidies to corporations like Ford (which did not in fact protect Windsor’s Ford engine facilities), why can they not provide funds for Windsor’s broader economic and social development? If a developing country like Venezuela can take advantage of its oil riches to address inequality and development in its country and region, why can a developed country not use its own abundant oil wealth to do the same?

The federal government currently has a budgetary surplus that it is largely – and wrongly – committing to tax cuts favouring the rich. That surplus and a special levy on all financial institutions (banks, investment houses, and insurance companies) could support a federal Social Investment Fund to finance the Job Development Boards. The money exists; the point is to mobilize the political power to access it.

Would this also mean higher taxes on working families? It might. But we should not run from this possibility. Taxes – equitably distributed – are an essential and solidaristic tool to advancing our goals.

7. From competition to democratic planning.

Meaningful democracy is about more than a form of government: democracy should also consider the form of society and social relations. It is in the economy that decisions are made about which goods and services are made, if we have jobs and investment, how the work is done, and who gets what. This obviously shapes our communities, choices, relationships – our lives. If the main elements of our economy are in a few private hands, and the basic decisions are dictated by their private profits, then – even if other important democratic rights exist – it is a pretty limited democracy that we live in.

The condition for moving on is that we place the issue of public control over investment, and democratic planning of the economy, on the agenda once again. It is only in that context that we can really start addressing the future in a way that does not condemn us to dependence on private corporations whose failure to deliver on a greater and more meaningful quality of life has already been demonstrated.

8. Ending NAFTA.

If corporations are free to subvert workers and unions in workplaces by moving or threatening to move their production, then they will frustrate any attempt to do things differently. This is where taking on ‘corporate freedoms’ – which undermine our freedoms – becomes fundamental. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) is not, as some argue, to blame for all our frustrations. But its explicit reduction of society to a collection of individuals connected by markets, and its ideological and material endorsation of corporate rights and freedoms, stand as barriers to extending our rights and freedoms. Taking on NAFTA is fundamental to any program of change.

9. From alternative policies to alternative politics.

The problem of course is not just identifying better policies but whether we can actually build the collective power to change things. Can we organize ourselves to overcome the bad ideas that have ruled our lives and start experimenting with new ideas that hold out some hope? What vision of society are we fighting for and how specifically might we organize ourselves to actually move closer to those goals? These are perhaps the most difficult issues of all. They are also the most important in the sense that without some answers – not necessarily ‘the’ answer, but at least some clear signposts – it will be near impossible to develop and reproduce the confidence to keep any campaign going, never mind extending it.

To many young activists, unions have become part of the problem, not the solution and they have focused their energy on building ‘social movements’. But however such movements might start, sustaining them will depend on the resources, organizational base, and strategic centrality of the one oppositional group that can do more than protest and in fact shut down production. The radical changes these movements demand will happen alongside unions or they will not happen at all. But if unions are to inspire this lesson, they will first have to transform themselves.

Rethinking Unions

1. Long-term visions are also needed.

Unions, reflecting their members’ immediate needs, are biased towards the short-term. The point, however, is not that the short-term and long-term are in opposition; ignoring the longer-term means that we repeatedly face the same limited and demoralizing options capitalism puts before us. Including the longer-term is about expanding those options and getting a larger perspective on daily pressures.

The issue is therefore how to bridge the two: how does what we do today weaken or strengthen our capacity to fight tomorrow? How do we defend ourselves in terms of immediate concerns, while also building the kind of unions and social movements we so desperately need for broader changes?

2. Concessions and fighting for alternatives do not mix.

It’s in this context that concessions – past gains given back to the corporations without a fight (or even sold by unions as ‘trade–offs’) – are so dangerous. Concessions implicitly teach the members, and suggest to the public, that it’s those past gains which are the cause of the problem, and so giving them up becomes the alternative and marginalizes discussions of other options. Moreover, once formal concessions are made in the collective agreement, management is in a position to further exploit this newly acknowledged weakness of the union through the informal mechanisms of aggressively attacking everyday working conditions and rights independent of what is or isn’t in the collective agreement.

The result is that the confidence of workers in taking on their employer is derailed, and the union is left vulnerable – understandably – to membership ambivalence about the unions’ very relevancy. So more than specific losses in benefits and rights are involved; the future capacity of the union to engage in struggles is also undermined.

3. Lobbying can never replace mobilizing workers and unions.

Similarly, a strategy based primarily on asking politicians to do something for us, even one based on organizing the occasional petition or protest, will bring us very little immediately nor contribute to building our future strength. If we take our own rhetoric seriously – that we’re facing something new and the threat is on a scale not seen before – then our response will have to match the scale of what we face, and to do so in novel ways. Of course we need to talk to politicians. But mobilizing, as opposed to lobbying, means concentrating on building our base and that even lobbying carries a weight beyond ‘relationships’ to corporations and politicians. It includes:

- providing the information and analysis local union leadership needs to get a handle on the issues with a level of confidence that encourages them to take that understanding to the members;

- engaging union activists and members in strategic discussions about what we must and can do;

- developing new cores of activists who are effectively organizers in the workplace and the community; and

- building the kind of collective capacity that can confront corporations and politicians with a measure of counter–power they can’t ignore.

4. Are existing union structures adequate?

Unions have been involved in impressive struggles of late – the minimum wage campaign in which the Metro Toronto Labour Council was so prominent, the drive by UNITE-HERE for a master agreement in the hotel sector among its predominantly immigrant women membership,

CUPE Ontario’s courageous step beyond collective bargaining and domestic issues to raise the rights of Palestinians for national self-determination (resolution 50). But none of this has added up to something that holds out the promise of reversing recent trends. What kinds of changes within unions are necessary to get beyond this impasse?

- What would transforming our unions imply for how we allocate resources in the union (e.g. what the research and education departments do, the role of the staff beyond bargaining, how much is invested in movement – building)?

- What does it mean for how we relate to and activate union members (including the development of the skills and confidence essential for real participation)?

- What does union renewal suggest for how we interact with other unions and with the community, and to what we expect of labour councils and labour centrals?

- How would it affect how we approach organizing – is it about adding members or building the working class to become collectively more powerful?

- How would union renewal shape how we think about ‘politics’ and also help push us past the broader impasse of the left and the socialist movement?

5. Social class exists beyond unions.

In their campaign on manufacturing jobs, the CAW has noted that it cannot overcome the crisis on its own and that broadening each union’s base across unions, and across the various social groups active locally, is absolutely crucial. To that end, it has argued for holding social forums in each community. This is a welcome step. But if we see the problem as not just the latest crisis in manufacturing, but as our general lack of effective power, then it is important to be more ambitious and think about permanent institutions through which class issues can be addressed.

The social forums might, along these lines, be seen as the start of a permanent structure – the Windsor Assembly on Restructuring the Community (or WARC) for an example – for representatives of union locals and community groups to meet on a regular basis, elect an executive, plan campaigns, run educational sessions, establish committees where people with particular interests could focus on common projects, and link up with allies beyond the community (e.g. in a fight against NAFTA).

If successful, this would of course raise further issues such as developing and maintaining the core of activists necessary to keep any organization going, and more systematic coordination across communities. But these and other issues are part of the dynamics of building a new movement. The immediate question is whether there is enough concern, interest and commitment to take some immediate steps towards coming together with a serious intent to challenge where we have been and where we could go.

Community Responses: The Example of Windsor

Although Canada’s average unemployment rate is at historically low levels, in Windsor is over 10% (about 15% if we include those who have dropped out of the labour market over the past year), and things look to get worse. Auto jobs can and must be fought for, but everyone concedes that even in the best scenario, this will not solve Windsor’s jobs crisis. The option of trying to become a tourism and convention haven that caters to business and the rich (satirized in Michael Moore’s ‘Roger and Me’) has become a default position for many de-industrialized cities in crisis, but Windsor can set its sights higher.

An alternative for Windsor might best begin, as suggested earlier, by asking: What kind of community can we imagine in Windsor? What is it that people here need in terms of goods and services? What capacities do we have (skills, machinery, tools)? What would it take to put together these needs, capacities, and potentials?

It seems useful to start with needs that have already been identified. Like other cities, Windsor has a long backlog of postponed municipal projects: roads and buildings that need repair; sewage and water supplies that need upgrading; warnings that if electrical generation concerns are ignored black-outs will surely come; improvement and extension of public spaces like parks, the waterfront and sports facilities; service gaps in quality childcare and supports for an aging population.

As well, Windsor has one of the highest rates of cancer in North America and addressing this has, tragically, been largely set aside. Windsor in particular cries our for the kind of environmental/social/jobs agenda some have long advocated: linking industrial clean-up, strong environmental standards, waste management and the creation of green spaces to Windsor’s abundance of facilities, tools and skills which can be converted to manufacture the environmental products that the future will demand (e.g. solar panels and wind farms, energy-saving appliances, new building materials, the massive project of recycling cars, the extension of public transit). Letting Windsor suffer through a job crisis and the destruction of a community, when Windsor can become a model of what could be done, would be a crime.

The election of a ‘Windsor Job Development Board’, recognized by the municipality, might be the first step towards focussing on a plan to relieve the crisis in Windsor. Along with this, Windsor could demand that $100-million be injected by the government to facilitate the creation of this Board and to introduce the emergency infrastructural jobs that Windsor, like other municipalities, has sitting on shelves awaiting some funding. That $100 million would of course only represent a first instalment. •

Also available as PDF format.