Ontarians for a Just Accountable Mineral Strategy (OJAMS) condemns the Wynne government’s recent decision to begin road construction to the Ring of Fire mineral deposit in 2019 without obtaining the free, prior and informed consent of the Matawa First Nations. This decision is not only in violation of the constitutionally-recognized rights of Aboriginal peoples, but also the Ontario Government’s Regional Framework Agreement with the Matawa First Nations finalized in 2014.

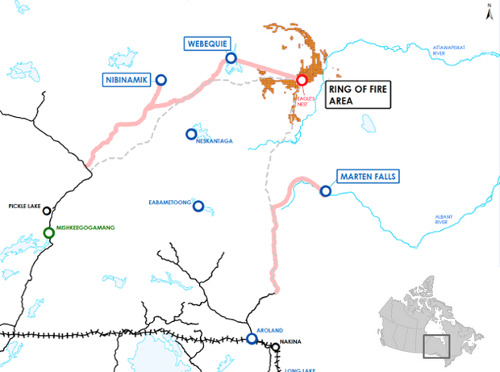

The Ring of Fire is a large, crescent-shaped mineral deposit containing chromium, copper, zinc, nickel, platinum, vanadium and gold. It is located in the traditional territories of the Matawa First Nations in the James Bay lowlands in Ontario’s Far North, site of one of the world’s largest remaining intact forest ecosystems. Hyped as Ontario’s version of the Oil Sands, the deposit has been said to contain $60-billion in mineral wealth. But after an initial staking rush in 2007, development stalled in 2014 following the collapse of the commodities super cycle. While mining industry proponents have blamed onerous environmental regulations and negotiations with Indigenous peoples for the delay, the reality is that the project cannot go ahead without significant public sector support.

OJAMS is composed of people from diverse communities and interests in Ontario that want to see a mineral strategy that:

- Sustains the environment and the resources for future generations,

- Protects the public from the risks associated with mining, smelting and refining,

- Heals the damage already caused by the industry,

- Captures a fair share of the revenues generated by the industry for Ontarians and First Nations, and

- Respects the rights of First Nations to free, prior, informed consent to development on their lands.

For more information, visit our website at www.ojams.ca.

The Ontario government decision announced on August 21, 2017 to fund a road to Ring of Fire mining claims over the objections of most of the Matawa First Nations has the mining and construction industry cheering. But the road is not going to happen unless there is consensus among the Matawa First Nations.

The plan is for three of the First Nations (Marten Falls, Webequie and Nibinimik) to be the proponents of the road project, with the province funding it. However, a condition of the funding is that the road has to service the Noront Ring of Fire claims.

The Ring of Fire is a large, crescent-shaped mineral deposit containing chromium, copper, zinc, nickel, platinum, vanadium and gold. It is located in the traditional territories of the Matawa First Nations in the James Bay lowlands in Ontario’s Far North, site of one of the world’s largest remaining intact forest ecosystems. Hyped as Ontario’s version of the Oil Sands, the deposit has been said to contain $60-billion in mineral wealth. But after an initial staking rush in 2007, development stalled in 2014 following the collapse of the commodities super cycle. While mining industry proponents have blamed onerous environmental regulations and negotiations with Indigenous peoples for the delay, the reality is that the project cannot go ahead without significant public sector support.

Marten Falls is now a shareholder in Noront. In April, 2017, the First Nation was given over 300,000 shares in Noront, in return for “fulfilling certain obligations and arrangements” [which are of course confidential]. With more than 327 million Noront shares outstanding, this is a drop in the bucket to Noront, but a serious compromise of Marten Falls’ position. Was one of the “obligations” that they would not publicly oppose the project? What are the restrictions on selling their shares?

Days after the announcement, Neskantaga and Eabametoong First Nations put out a press release (Aug. 24) stating:

“The reality is that all the roads to the Ring of Fire traverse the territory of our Nations, and nothing is happening without the free, prior, and informed consent of our First Nations,” said Neskantaga Chief Wayne Moonias.

“Neskantaga and Eabametoong First Nations have been actively working to have their rights recognized by Ontario, along with all 9 Matawa-member First Nations, at the Regional Framework Negotiations and the Jurisdiction Table. Both of these processes are intended by our Nations to be collective, community-driven discussions.

“… Citing a ‘divisive’ approach as being behind the Wynne Government announcement, the two communities of Neskantaga and Eabametoong pledged to honour their respective community processes and to ensure that a concrete agreement over First Nations jurisdiction is actually in place as a pre-condition to road approvals. The Elders and Youth of both communities have stated their support for the positions taken by the leadership.”

In May, 2017, Wynne had threatened the Matawa Chiefs

“‘My government announced $1-[billion] to support infrastructure into the Ring of Fire three years ago and if we are going to deliver on that we can delay no further,’ Ms. Wynne said in the letter, which was obtained by The Globe and Mail. ‘While I continue to hope progress can be made, I am prepared to continue to advance discussions with those First Nations that would like to pursue transportation infrastructure through our bilateral processes.’”

She and her government have since pursued exactly that divisive strategy. Her government cut a backroom deal with three of the Chiefs.

The Chiefs of Nibinamik and Webequie scrambled to explain their position. On August 25, they held a press conference in Thunder Bay to “clarify Wynne’s announcement”. Reported APTN:

“Webequie First Nation Chief Cornelius Wabasse and Nibinamik First Nation Chief Johnny Yellowhead said they did not agree to construction of the all-season road, but rather a study of the feasibility of a ‘multi-purpose corridor’ that could include a road, transmission lines and other infrastructure needed to underpin expected Ring of Fire development.”

Noront is Desperate for the Road to be Built

Noront, which now holds 75% of the Ring of Fire claims, is getting desperate for the road to be built. From the beginning of their investment in the Ring of Fire, the company has said the road (which will cost a minimum of $1-billion, and likely much more) has to be paid for by the province.

The company is deeply in debt to Resource Capital Fund ($15-million due at the end of the year), and has already had one extension of the loan. Through one of their subsidiaries, they also owe $25-million to Franco-Nevada, due in 2020.[1]

Federal and Provincial Government Subsidies

Noront has raised the capital it needs to exist through many issues of flow-through shares. This is a federal and provincial program that allows the costs of exploration and development expenses to be claimed by investors that need tax write-offs. The foregone taxes, and the credits that go with them, affect all of us.

The province and the federal government have basically paid for most of the First Nations consultation, paying salaries for the lawyers, technical consultants and community mining advisors, including the Ring of Fire Secretariat, Bob Rae and Frank Iacobucci.

The federal government put in $15.98-million from 2010 to 2016 through the Strategic Partnerships Initiative “to support first nations mining readiness activities in the Ring of Fire. In 2016, the government announced it was extending this program for another three years.

The federal government also funds a program called Comprehensive Community Planning (in the amount of approximately $700,000). This appears to be at least part of the $200-million Carolyn Bennett said would be spent on indigenous children.

What else could have been done in the Mattawa communities if the money were used for supporting kids, housing, water, and sustainable job creation instead? As Bob Rae commented to CBC: “‘This can’t be a process that is driven exclusively on the interests of one project or another,’ Rae said. ‘It has to be seen as responding to a broader concern which is the isolation, the poverty, the real needs of these communities.’”

Former federal Natural Resources Minister Greg Rickford is on the Noront Board.

No Feasibility Study for Ring of Fire Chromite

No feasibility study has been completed on the chromite deposits. Cliffs Resources walked away from the project just as the feasibility study they commissioned was to be finished and sold the project to Noront for $22-million. The only feasibility study undertaken to completion was for Noront’s Eagle’s Nest project; a carrot-shaped deposits of nickel, copper and PGM metals. It made it clear that the project needed the province to put up the road/rail costs or Eagle’s Nest could not be built.

The other question hanging over the Ring of Fire is the need for a ferrochrome smelter to process the ore. The location of the project is again in question, with Sault Ste Marie, Timmins and Sudbury all in competition for it. That smelter cannot be economic without serious electricity subsidies, in a province where electricity costs a great deal to produce.

Conclusion

Ontarians for a Just Accountable Mineral Strategy (OJAMS) condemns the Wynne government’s recent decision to begin road construction to the Ring of Fire mineral deposit in 2019 without obtaining the free, prior and informed consent of the Matawa First Nations. This decision is not only in violation of the constitutionally-recognized rights of Aboriginal peoples, but also the Ontario Government’s Regional Framework Agreement with the Matawa First Nations finalized in 2014.

There is simply no need to rush road construction to the Ring of Fire. Despite all the fanfare, industry insiders know the Ring of Fire is “just another mine.” As the editor of one of the industry’s leading journals, The Northern Miner, put it: “There’s really an oversupply of chromium. You can mine chromium by going to a waste dump in South Africa, so there’s not a great need for a new source.” Should the people of Ontario let its government spend billions of dollars and override the constitutional rights of Aboriginal peoples for something that can be found in a waste dump? OJAMS says no. •