Two Essays by Sotiris

(1) Beyond ‘Realism’:

Greece, the challenges for the Left and the need for a radical strategy

For the past three years Greece has been at the same time an experiment in neoliberal social engineering and a laboratory of movements and collective struggles. For the first time in many decades we have the case of a country entering a phase of profound social and political crisis that has the potential to turn into a crisis of hegemony opening up the social and political space for a sequence of social transformation. That is why the Greek case brings forward not only the depth of the crisis of the project of European Integration, the extreme violence of contemporary neoliberal policies, but also the need for a redefinition of left-wing or radical politics that could go beyond simply resisting austerity toward a new conception of a socialist alternative.

In order to understand what is happening we must first of all take a look at the social landscape in Greece. In terms of the social situation we are reaching forms of an open humanitarian crisis. Recession has reached proportions that can only be compared to the consequences of major warfare or of the 1930s Great Depression with a -25 per cent GDP contraction in the 2008-2013 period. Unemployment is at 27 per cent with youth unemployment at 64 per cent, creating a “no future” generation and leading to increased migration, including a “brain drain.” Real wage reduction is at -30 per cent for most of the workforce, with new wage cuts coming in the near future. Health indicators are already showing signs of deterioration along with an impressive rise in suicides. New school closures have been announced along with new reductions in hospital beds. Increased homelessness, soup-kitchens and widespread drug use, also give an image of social devastation.

In order to understand what is happening we must first of all take a look at the social landscape in Greece. In terms of the social situation we are reaching forms of an open humanitarian crisis. Recession has reached proportions that can only be compared to the consequences of major warfare or of the 1930s Great Depression with a -25 per cent GDP contraction in the 2008-2013 period. Unemployment is at 27 per cent with youth unemployment at 64 per cent, creating a “no future” generation and leading to increased migration, including a “brain drain.” Real wage reduction is at -30 per cent for most of the workforce, with new wage cuts coming in the near future. Health indicators are already showing signs of deterioration along with an impressive rise in suicides. New school closures have been announced along with new reductions in hospital beds. Increased homelessness, soup-kitchens and widespread drug use, also give an image of social devastation.

Political Earthquake

In terms of the political crisis there has been a growing estrangement of the large segments of the popular classes from pro-austerity parties and the political system. This found its expression in negative feelings and attitudes toward the political system, mainstream parties and a growing feeling of anger and distrust toward the European Union, including Greece’s participation in the Eurozone. Large segments of the popular classes, of workers, employees, peasants, youths, members of the “professional classes,” small businessmen, have turned their back on mainstream parties, leading to a political earthquake in the May June 2012 elections when both PASOK and New Democracy suffered great losses and SYRIZA came close to winning the June election and gaining governmental power. One can see the same elements of an open political crisis even in opinion polls. SYRIZA and New Democracy are running neck and neck for the first position, whereas the once dominant PASOK is polling between 6 and 8 per cent.

However, treating these tectonic political shifts as the simple result of social crisis and the deterioration of social conditions is far from providing a full image of the situation in Greece. Without a unique and without precedent sequence of struggles and collective practices of resistance and solidarity, without a strong movement, which has been close to a modern version of a “protracted people’s war,” we would not have experienced these political earthquakes. It was exactly through these collective experiences of struggle, this feeling of anger turned into hope, this feeling of confidence and of being part of a people in struggle, expressed in concrete practices such as a demonstration, a clash with the police or a popular assembly, that people were again re-politicized, re-radicalized, moved to the Left. Were it not for the mass strikes, for the continuing struggles in many sectors, for the hundreds of solidarity initiatives, and for the many forms of resistance and disobedience, the political landscape would have been much more different.

I would like to insist that when we talk about the experience of struggle in Greece, we are not talking simply about mass riots and whatever catches the attention of international media, but about a much more complex set of collective experiences and struggles. Apart from general strikes, we have had a whole series of labour confrontations both in the public and the private sector. To give an example, despite efforts from the government including continuous parliamentary ‘coup d’etats’ (in the form of ‘special legislation

measures’), the government is far from reaching the quota for public sector lay-offs dictated by the Troika. Teachers in Secondary Education massively voted in favour of striking during the university entry exams, forcing the government to issue an authoritarian ‘back to work’ order. In Universities there have been important struggles in the past months against mandatory closures and mergers of Departments and Schools, struggles that in some cases, such as the Athens University Faculty of Letters, were victorious. In Chalkidiki, in the North of Greece, local communities are still waging a heroic struggle against environmentally disastrous Gold mines, despite being treated as terrorists by the police and the justice system. At BIOME, a factory near Salonika we are already witnessing the first successful example of a self-managed factory. In many cities local citizen initiatives and popular assemblies are working with the farmer’s cooperatives in order for cheap quality agricultural products to be available to working people. Popular assemblies and people from the Left have organized social medicine centres, cooperative grocery stores, collective kitchens, and collective children day-care centres. Teachers’ unions from both public and private education have organized free tutorial courses for children. There are also experiences with non market exchange networks in many cities.

At the same time there has been a flourishing of anti-fascist initiatives and demonstrations, along with struggles against the exploitation of immigrant workers. Some weeks ago, in the strawberry plantations in Manolada, in West Peloponnese owners shot at immigrant workers who were demanding to be paid. The reaction was not only impressive demonstrations which united Greek and immigrant workers, but also an impressive organization drive toward the first such union of agricultural labourers in Greece.

I am stressing this because in many instances the Greek Left and especially SYRIZA acts as if political power and consequently an end to austerity and a beginning of social transformation will simply come as the ‘ripe fruit’ of worsening social conditions. Nothing is further from the truth. Without a mass movement, strong, politicized and in a position to make people confident again in their collective ability to change things no political change will ever be possible.

What is more important, is that time matters! Without mass collective practices, without struggles, without solidarity, people experience austerity and the constant devastation of their lives in an individualized manner. This doesn’t breed rebellion. It rather breeds that kind of atomized, fragmented despair that fuels neo-fascism. If we look at the people following the neo-fascist Golden Dawn we will see that leaving aside these people that come from the traditions of the Greek far right, most of the people supporting Golden Dawn are people who are channeling exactly this kind of individualized despair toward the extreme reactionary discourse of Golden Dawn and its ersatz ‘solidarity only for Greeks.’

I know that many people will raise the objection that simply building a strong movement is not enough, since despite three years of general strikes (more than 25 since the Spring of 2010), mass occupations, impressive protests such as the Movement in the Squares from May to July 2011, big street clashes, various forms of civil disobedience to tax hikes, successive governments have managed

to pass one austerity bill after the other. Doesn’t this stress the fact that only through a political solution, only through a change in what concerns governmental and political power, can we find a way out of the vicious circle of austerity, recession and unemployment?

Post-Democracy?

It is obvious that Greece has entered what one might describe as a post-democratic condition. The traditional forms of political pressure that could force a government to step back from introducing reactionary measures through a calculation of the political cost, do not apply to Greece anymore. On the contrary, we have entered a condition of limited sovereignty, with the EU-IMF-ECB ‘Troika’ dictating measures regardless of their social cost and with Greek governments simply capitulating to these demands, under the pressure of the dominant fractions of Greek capital. Without a political breakthrough, without a sharp change in the political balance of forces in favour of the forces of labour and other popular classes, there can be no end in sight in the politics of austerity. We need such a broad popular alliance under the hegemony of the force of labour that will take governmental and political power and open up a political sequence of social transformation in a socialist direction. In sum what we need is to actually try and think how today’s dynamics of anger, contention and protest can be turned into a highly original revolutionary process, revolutionary in the sense that it must challenge fundamental aspects of capitalist social relations and highly original because we cannot think about it in terms of ready-made conceptions.

Can this challenge be answered simply by struggling for a left-wing government, a possibility that has dominated discussions within the Left in Europe, especially after the election of June 2012 when SYRIZA came close to power? First of all, this possibility represents the depth and the extent of the political crisis in Greece, the tectonic shifts in relations of political representation, as a result of the social crisis but also of the impressive series of struggles and collective practices of resistance, protest, disobedience and solidarity. At the same time it brings forward the centrality of the question of political power in the current conjuncture in Greece. However, although the whole

question of a possibility of a left-wing government opens up the question of political power, this does not mean that SYRIZA, at least in its current policies and strategic proposals is the answer. That is why it is important to rethink questions of political and governmental power.

The first question arising when discussing such matters refers to the question of the program of any attempt to fight for political power. For many people, questions of political program might seem like a luxury. For them what we need is to unite forces around simple demands, around this necessary ‘no to austerity,’ instead of endless discussions on the program. However, there are aspects of the political program that do not represent ideological obsessions but attempts to come to terms with important material constraints for any potential left-wing politics. Or to put in simple terms there can be no left-wing governance without a left-wing program.

To give perhaps the most important example, the question of the relation of Greece to Eurozone and the European Integration project in general is not an ideological obsession from the part of some tendencies of the Greek radical Left. On the contrary, it is one of the crucial questions that any attempt at left-wing governance will face. The European Union today is not simply turning

more neoliberal (especially if we consider the embedded neoliberalism of the European Integration project since the Single European Act of 1986), it is also turning into a highly undemocratic process, openly calling for limited sovereignty for countries in the European South, creating conditions of a ‘race to the bottom’ of austerity, recession and unemployment, using in many instances an openly neo-colonial rhetoric on the need to “reform those lazy Southerners.” The euro is not simply a currency, but represents a whole set of institutional restraints and obstacles to any progressive policies. At the same time it is an imperialist strategy. The euro as common currency in an economic area marked by sharp differences in productivity and competitiveness acted as an extra “comparative advantage” for the capitals of the hegemonic European social formations, such as Germany and as an “Iron Cage” of capitalist modernization for peripheral social formations. In a period of economic crisis it also enhances structural imbalances, inequalities and divergences, thus contributing to the debt and the general economic crisis of countries such as Greece.

The Euro also forms the material ground of all forms of blackmail that any left-wing or progressive government will face in Greece. To put simply it is not possible to negotiate or take a firm stand against the austerity measures imposed upon Greece when the Eurogroup controls monetary policy, when the European Central Bank controls the liquidity of banks, when a country remains dependent upon loans from the ECB and the IMF. Regaining monetary sovereignty, as a form of democratic social control of an important aspect of the economy is a necessary precondition for any potential progressive solution to the Greek problem.

I know that the counterargument is that a left-wing government, armed with the support and aspiration of the electorate will be in a position to take a firm stand against the EU-IMF-ECB Troika, renegotiate successfully, obtain important concessions and put an end to austerity. However, I think that this is as close to a fantasy that we could get! That is why Cyprus offers an important example and a warning that we cannot avoid taking into account. What happened in Cyprus? The EU-IMF-ECB Troika imposed a very aggressive austerity program. The Cypriot Parliament rejected this program, under the pressure of the people who were demonstrating in the streets. The Cypriot government went to Brussels to renegotiate, taking a firm stand and demanding a better deal. However, it was also determined to stay within the monetary and institutional framework of the Eurozone. The result was that it got an even worse deal than the original in terms of recession, austerity and unemployment. How can we be certain that a SYRIZA government determined to get rid of austerity while remaining within the Eurozone, will not get the same treatment and succumb to the same kind of blackmail? The argument that Greece is ‘too big to fail’ does not hold, since by now it is obvious that most countries, central banks and international organizations are in a position to withstand the bankruptcy of a country like Greece.

I know that the counterargument is that a left-wing government, armed with the support and aspiration of the electorate will be in a position to take a firm stand against the EU-IMF-ECB Troika, renegotiate successfully, obtain important concessions and put an end to austerity. However, I think that this is as close to a fantasy that we could get! That is why Cyprus offers an important example and a warning that we cannot avoid taking into account. What happened in Cyprus? The EU-IMF-ECB Troika imposed a very aggressive austerity program. The Cypriot Parliament rejected this program, under the pressure of the people who were demonstrating in the streets. The Cypriot government went to Brussels to renegotiate, taking a firm stand and demanding a better deal. However, it was also determined to stay within the monetary and institutional framework of the Eurozone. The result was that it got an even worse deal than the original in terms of recession, austerity and unemployment. How can we be certain that a SYRIZA government determined to get rid of austerity while remaining within the Eurozone, will not get the same treatment and succumb to the same kind of blackmail? The argument that Greece is ‘too big to fail’ does not hold, since by now it is obvious that most countries, central banks and international organizations are in a position to withstand the bankruptcy of a country like Greece.

On the contrary, the unwillingness of the leadership of SYRIZA to even consider the possibility of a rupture with the European Integration process and the mechanism of debt-ridden austerity, leads it to make proposals that are not only out of touch with the reality of power relations in the international plane, such as the proposal for a “New Marshal Plan” for Europe, but would also lead to an even greater dependence of the Greek economy on the funding from international organizations.

Exit From the Eurozone?

There is nothing nationalist or chauvinist in opting for the exit of Greece from the Eurozone. Unless we think that it is nationalist and chauvinist to fight for a rupture with the violence of neoliberalism and the imperialist character of the monetary and fiscal architecture of the Eurozone. As for the argument that it is better to wait for a pan-European movement to get rid of austerity, I believe that this argument misses an important aspect of social struggles in Europe, namely the uneven character of their development. Not all movements are equally radicalized and politicized and adopting such a strategy of waiting for a Pan-European movement will mean that the people in Greece will endure many more years of austerity and social devastation. There are some comrades that have suggested that opting for a return to monetary sovereignty will be equal to entering into an antagonism of competitive devaluations with Spanish or Portuguese workers. I also think that this is far from the truth. Getting Greece out of the Eurozone is not about competitive devaluations but about protecting large segments of the popular classes against the systemic social violence of the free movement of capitals and commodities across the European Union, about regaining democratic social control of the monetary policy and the economy in general, and about attempting to rely on the collective effort of working people to build an alternative future instead of being prey to the embedded neoliberalism of the European Integration Project.

Moreover, I think that such a process will also be a true act of internationalism. Wouldn’t it be a message of hope and a proof that social change is possible if social movements in a country of the

European South managed to break away from the Eurozone and begun a process of social transformation? Wouldn’t this be the first step in getting rid of the euro and all the neoliberal and undemocratic framework of the European Union? Wouldn’t this open up the way for new forms of cooperation based on respect for democracy, popular sovereignty and common effort for a better future?

In light of the above, recent interventions in the debates within the European Left in favour of a strategy of exit from the Eurozone, are more welcome. The decision of AKEL to consider the possibility of Cyprus exiting the Eurozone, the report by Heiner Flassbeck and Costas Lapavitsas [Ed.: see below for more on this report] on the crisis of the Eurozone, and the public intervention by Oscar Lafontaine in favour of a potential “Grexit,” all these represent a welcome change and open up the space for a real discussion of radical alternatives.

I do not want to suggest that the question of an alternative policy for Greece is limited to questions of monetary policy. Nor am I criticizing SYRIZA in the name of some abstract ‘anti-capitalism’ like the one offered by the Greek Communist Party who talks about socialism but only in another time, since today ‘conditions are not ripe.’ What I am trying to suggest is that any possibility of an end to austerity must start with a set of urgent measures that are immediately needed in order to avoid social disaster and at the same time open up the way for a radical transformation of Greek society in a non-capitalist direction. These measures should include apart from the immediate exit from the Eurozone and potentially the EU, the annulment of debt, the nationalization of banks and strategic enterprises and redistribution income in favour of the forces of labour including a re-establishment of full trade union rights to organize and collectively bargain. Institutionally, this process should not be conceived in terms of remaining within the contours of existing legality (both national and European). On the contrary it will require a new ‘Constituent Process’ and deep changes that should include limitation to capitalist ownership, the right to occupy and self-manage abandoned or closed enterprises, and new and extended forms of social and workers’ control. It is on the basis of such measures that we can really start thinking about radical changes in a socialist direction, in the sense of extended self-management, alternative forms of non-market distribution, new forms of democratic social planning, socialization of knowledge and expertise, new forms of democratic participation at all levels of decision-making.

Implementing such measures will not be easy and it will require a new collective ethics and a strong sense of common effort and participation. That is why it is necessary to think of this challenge not in terms of governance but of a movement, of a collective process of transformation. Moreover, only a strong movement from below, in the sense of extended forms of trade union action, of forms of popular democracy from below, of networks of solidarity, of forms of self-defence, can mount a successful resistance to all forms of formal and informal sabotage and counter-attacks from the part of the forces of capital, the justice system or the repressive apparatuses of the State.

Revolutionary Strategy

All these bring forward an important question. It is not possible to deal with questions of left-wing government and its relation to the movement without opening up the question of a revolutionary strategy in the 21st century. Contrary to the position held by both SYRIZA and the Communist Party, that today there is no point in talking about revolutionary changes (in the case of SYRIZA in the name of the immediate need to avoid social disaster and in the case of KKE of the situation not being ripe enough), I want to stress that what has been happening in Greece in the past three years in terms of social protest and contention, of open political crisis, of people abandoning mainstream parties and politics and being ready to accept radical solutions, of a demand of profound social and political change, of an acceptance of the need for new social and political configuration beyond ‘actually existing neoliberalism,’ is the closest we could get to potentially pre-revolutionary situation. Of course, the situation is in a way unripe and immature, but hasn’t this been the case with all sequences of major social and political transformation? However, this need for a new – and necessarily original – revolutionary strategy should not lead us to a dogmatic reproduction of either the ‘democratic road to socialism’ position or the traditional insurrectionary conception of the revolutionary process. On the one hand we need to take into consideration that in advanced capitalist societies with developed forms of civil society institutions and extended apparatuses of hegemony it is necessary

to conduct a modern version of ‘war of position,’ a complex attempt at creating forms and institutions of counter-power and counter-hegemony from below in a new and original form of a ‘dual power’ strategy. On the other hand we need to find ways to accelerate and intensify processes of political and potentially hegemonic crisis and take advantage of any opportunity to bring reactionary governments down under the pressure of the movement and use the window of opportunity opened by the possibility of a left-wing government along with an escalation of struggles and confrontations with the logic of capital on all levels.

What is needed is an attempt to transform contemporary dynamics within Greek society into something close to an “historical block” to use Gramsci’s term, not simply an electoral alliance, but the encounter between an alliance of the subaltern classes, a radical anti-capitalist program, in the sense of an alternative narrative, and new collective forms of organization and experimentation. Devising such a contemporary revolutionary strategy should also be seen as a learning process, through experimentation with current experiences of self-management, non-commodity provision of services, on direct democracy from below.

However, most tendencies of the European Left do not even attempt to open up this debate, remaining entangled either in “realist” proposals for a progressive governance that will not challenge the power of capital or the current architecture of globalized capitalism, or in revolutionary fantasies about “storming the Winter Palace.”

And this is the problem with SYRIZA leadership’s strategy. They treat the question of governmental power as a means to bring forward progressive reforms and gradually put an end to austerity. To this end they take for granted all the institutional constraints of the Eurozone and the bail-out loan agreements. That is why they moved from a position of complete renunciation of the loan agreements to a position of “renegotiation.” That is why they have been trying to develop a better understanding with representatives of big business, including media barons. That is why there have been references from the part of SYRIZA to sound entrepreneurship and socially responsible ‘investments.’ I do not wish to deny the radicalism and the good will of many comrades in SYRIZA and their commitment to socialist politics, but the truth is that the current strategy by SYRIZA is far from answering these challenges.

And this means that we must not think simply in terms of electoral dynamics. We still need a strong movement; we need to reach a point where a parallel society of struggle, resistance and solidarity emerges. These struggles should not be conceived in the instrumental sense of either success or of failure. As I have already mentioned, traditional calculations of movement pressure do not apply to Greece. We need more to think in terms of a protracted peoples’ war in which the crucial point is not whether there is ‘victory’ in the sense of an austerity bill not passing because of a mass strike, but more in terms of a constant attrition of the government and the Troika, of delays or blockages in aspects of the austerity measures, and of a growing collective confidence within the movement that in the end we can win. Solidarity in the sense that people can be confident that through the collective practices they will avoid having their electricity cut-off, their home auctioned, that they will be able to cater for basic needs from food, to medicine to tutorial courses for their children, is extremely important, since it brings back confidence to collective struggle and the ability to build a better future.

At the same time, these collective practices must be seen also as the emergence of forms of popular power from below, as forms of an emerging contemporary form of dual power, as forms of

self-defence against the aggressiveness of the government and the forces of capital. Underestimating the importance of a strong movement and prolonged struggles means underestimating the dynamics of the class balance of forces. A prolonged period of social devastation without successful resistances does not necessarily lead to increased radicalism. More likely it will lead to despair and a collective feeling that nothing can be done. That is why political decisions regarding movements are crucial. The recent developments regarding the Secondary Education Teachers’ strike are in this sense revealing of the deficiencies of tactics of the Left. The decision of the leadership of SYRIZA to agree on calling off the strike, instead of attempting to break the government ‘back to work order,’ was an expression not only of a deep rooted reformism but mainly of a conception of politics as electoral politics, not as an attempt to influence the real balance of forces. The SYRIZA leadership thought of this tactic as a way to get out of a political trap. In reality this decision only reinforced the government’s rhetoric that it is in a position to pre-emptively smash a movement. What can remain after such a confrontation are not only anger and protest against authoritarian measures, but also disappointment and a feeling of futility.

Above all, we need to think of this whole process not simply as an attempt by a progressive or benevolent government to save society but as a mass movement for the experimentation with new forms of organization of production, education, health. We need to make use of the collective experience and knowledge that have emerged in the movements and struggles of the past years for this experimentation that cannot be left to specialists, even from the Left. The crisis and austerity in Greece have been a catalyst for many people, who faced with extremely aggressive policies are obliged to think differently. When the government is dismantling public education, militants in education trade unions are forced to think how we can operate schools differently. When the public health is in ruins and is kept in place only by the efforts of doctors and other health workers, then public health unions face the question of what it means to actually run a truly public health system oriented toward improving the quality of life. This is exactly the kind of collective experimentation that can provide as with concrete answers regarding a contemporary socialist strategy.

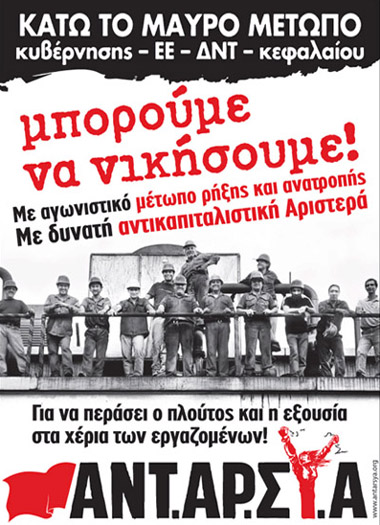

Are there signs of such processes in Greece today? Or have we arrived at an impasse and there is no other alternative than simply waiting for the next general election in the hope that the Left will get the mandate to form a government? I think that we are far from this. We may not have had in the past months the kind of social explosion that gain the attention of international media, but everyday struggles continue in the form of small and big battles in various sectors, solidarity initiatives, and anti-fascist demonstrations. At the same time, things are changing in the trade union movement, the Left is on the rise in important unions such as in public education and public health and this opens up the possibility for a radical reorientation. Moreover, there is an open debate regarding the question of the political program and there are signs of mass appeal of a radical anti-EU, anti-euro position, especially after the experience of Cyprus. The current dialogue between ANTARSYA, the front of the anti-capitalist Left, and other radical groups in Greece, opens up the way for a ‘third pole’ in the Greek Left that will insist on the actuality of such a radical political alternative, in an attempt to change the balance of forces within the Left.

What is to be done? I think that the answer, at least for all of us in the Greek Left, in ANTARSYA and other radical formations, that do not opt for a tactic of simply hoping that we will somehow push SYRIZA to the Left, and at the same time do not want to engage in a destructive and sectarian criticism (like the one coming from the part of the Greek Communist Party), is to attempt to deal with the real challenges: To elaborate on the necessary transition program. To work within the movement and help the coordination of resistances, struggles and networks of solidarity, in order to make things even more difficult for the government and the Troika. To experiment with forms of self-management, self-organization and popular democracy from below.

Therefore, we are far from the end of the movement. I think that despite the efforts from the part of the government, the Troika, the forces of capital to suppress collective practices, and despite the effort of the leadership of SYRIZA to channel this dynamic into a fruitlessly ‘realist’ strategy of renegotiating austerity, Greece is still the most advanced laboratory of struggle and radical

alternatives in Europe, and I hope that it will soon send a message of hope to working people all over Europe. •

This text is based on two presentations at the “Marx is a Must” Conference in Berlin (9-11 May 2013), organized by the Marx 21 network, and first published on his blog at lastingfuture.blogspot.gr.

(2) Exit From the Eurozone

The elephant in the room or why we cannot have socialism based upon EFSF recapitalization

Panagiotis Sotiris

The report by Heiner Flassbeck and Costas Lapavitsas on the crisis of the Eurozone has been an important step in re-opening the euro debate within the European Left.

The political significance of the report was made even more evident by the fact that it was published by the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung, and was endorsed by the leadership of Die Linke, especially after Oskar Lafontaine had also recently insisted on the need to consider the exit from the Eurozone as a potential solution for countries of the European South such as Greece. It follows the decision by AKEL the Cypriote left-wing party to propose Cyprus’ exit from the Eurozone, a proposition based upon scientific advice offered by amongst others Lapavitsas and Flassbeck.

The report itself is not a radical or Marxist manifesto. Although Lapavitsas has a strong Marxist background, the report is marked by Flassbeck’s much more Keynesian approach. Moreover, it is not a report with an a priori hostility toward monetary union or currency coordination for Europe, nor is it filled with anticapitalist references. On the contrary it seems to take the internationalization of trade and capital flows as granted. However, it is exactly this kind of critique from within aspects of the dominant economic paradigm that makes it even more interesting.

This does not mean that it is not a radical critique of the dominant economic policies within the Eurozone. Rather, it is a devastating deconstruction of the contradictions, fallacies, and shortcomings of the economic and financial architecture of the Eurozone. Particularly important is the emphasis on the inability of inflation targets without real wage convergence to create a balanced common currency area. Moreover, the two writers highlight the direct causal connection between the imbalances in the Eurozone and trade deficits and also with increased public debt. This makes evident the fact that European leaders insist on denying: the euro itself as common currency is part of the problem of the economic crisis in the European South.

It is also interesting that the position the two writers take in regard to potential solutions within the Eurozone. They show convincingly that given the obvious inability to reach an actual political union in the EU it is not possible to have that kind of redistributive mechanisms that could tackle the problem of productivity and competitiveness divergence. At the same time they remind us that there is no point in thinking in terms of transfers between countries because this could lead in a certain form of dependence of the countries receiving this kind of transfer funding.

On the basis of these assumptions the two writers insist on the need for an orderly and prepared exit from the Eurozone and in this sense a dismantling of the current financial and monetary architecture of the Eurozone. To this end they also deconstruct the argument that such a move, which would necessarily include measures such as capital controls and restrictions to bank transactions, is not possible, by pointing to the developments in Cyprus where the EU accepted the imposition of capital controls as a means to avoid the complete implosion of the Cypriot banking system. In this sense the taboo has already been broken.

In light of the above it is really interesting to see the reactions of the Greek Left and especially SYRIZA regarding these positions. As with the case of the change of AKEL’s adoption of the exit from the Eurozone strategy, SYRIZA leadership chose to politely refuse such proposals, despite the appeal of this position in the large segments of the electorate of the Greek Left. In many instances representatives of the leadership’s position within SYRIZA have criticized the exit from the Eurozone as being nationalist and in opposition to class politics.

However, the problem is that the dominant narrative of SYRIZA leadership that the main target must be pan-European cooperation of the Left and social movements aiming at a break of austerity while remaining within the Eurozone, comes in contrast with the decision of other parties of the European Left to discuss the possibility of an exit from the Eurozone.

The argument from the part of SYRIZA leadership that opening the debate on the exit of the Eurozone would offer pro-austerity forces the chance to put pressure on SYRIZA, alienate segments of the electorate (who remain ideologically attached to the euro), and consequently jeopardize a possible election victory, misses the main point. As long as the Greek Left does not challenge the euro as the central node for the current particularly European version of the neoliberal “There Is No Alternative,” the political debate will remain cornered in a discursive terrain that is much more suitable to systemic pro-austerity forces than to social movements. This helps pro-austerity forces, both politically and electorally. In contrast, working toward the break with the Eurozone opens up the political space to work and experiment with radical economic and social alternatives that go beyond the limits of neoliberal capitalism and can help the Left emerge as an actual political alternative and not just an electoral outlet for protest. Moreover, it is not possible to have radical changes without some form of rupture with the current financial, monetary and institutional framework of the Eurozone and the dominant strategy within the EU.

In the long run, everyone would agree that we cannot have socialism based upon EFSF and ECB recapitalization. •