Rethinking the ‘Indian International Student Crisis’

In downtown Toronto, whether it’s the chime of an app alert or the hum of two wheels weaving through rush-hour traffic, the faces you see delivering food, stocking shelves, and filling low-wage shifts are disproportionately South Asian migrants. What official discourse calls an “international student crisis” is not primarily a crisis of numbers but a crisis of labour: a structurally produced, politically managed supply of cheap, precarious workers that Canada’s universities, employers, and state have come to depend on. As federal policy has turned post-secondary education into a revenue engine, and work restrictions wax and wane with labour market needs, hundreds of thousands of international students have been funnelled into the gig economy, warehouses, kitchens, and service jobs that remain deeply undervalued, yet essential to the functioning of everyday life.

The frenzy over “unchecked” migration obscures this reality. Rather than a spontaneous influx of opportunistic newcomers, the recent growth in international student numbers reflects a carefully engineered labour strategy. Students are touted as economic windfalls – high tuition fees that prop up cash-strapped institutions and workers who fill staffing gaps, big and small – yet their precarity is treated as incidental to policy. Poverty wages, debt-financed migration, and the threat of falling out of status are cast as the expected price of pursuing an education here, even as the state and corporations quietly rely on these same workers to power sectors that Canadian workers increasingly shun.

Yet even as international students have become hyper-visible in Canada, their categorization now unknowingly, and quite deceptively, includes those who could not continue their education for various reasons, those who have graduated, and those who have become undocumented. In 2023-2024 alone, nearly 7,000 media articles mentioned international students. Yet this heightened visibility obscures more than it reveals. Much of the furor surrounding South Asian migrants obscures how the figure of the recent South Asian migrant, often collapsed into the label of the “international student,” has become a testing ground for the expansion of precarious and gig labour, as well as for the consolidation of Canadian nationalist sentiment. While the relationship between capital and the nation is complex and contested, their overlapping interests demand a closer reading of the catch-all term “international student,” which deliberately masks questions of labour, class position, and exploitation.

The ‘Other’ in the New Canadian Nationalist Wave

The resurgence of Canadian nationalism in the past year – ostensibly a response to US tariffs – has intensified racial and class anxieties. For the first time since Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada began polling in 1996, a majority of Canadians say there are too many immigrants coming to the country. For the first time, debates about international students featured prominently in the 2025 Canadian federal election campaigns, with both Conservatives and Liberals advocating cuts to international student intake. Public discourse frequently positions recent South Asian migrants or international students as contributors to rising housing prices, job scarcity, and a perceived lack of cultural integration.

So-called “Canada first” rhetoric purports to prioritize the welfare of Canadian nationals. Addressing a press gathering in 2024, Conservative Party leader Pierre Poilievre described the “international student crisis” by stating, “It’s not about immigration; it’s about math.” His claim that the housing crisis necessitates a crackdown on migration obscures structural issues such as corporate greed and the reality that the housing crisis is not caused by immigrant students, many of whom live eight to 15 people in an apartment. Nonetheless, the simplicity of reactionary rhetoric appears compelling, as it suggests that there are simply not enough resources to go around.

This framing also obscures a more uncomfortable truth: the state is not merely failing to manage international student migration but actively relying on it. Senior federal officials have openly acknowledged that international students fill labour shortages in retail, food service, logistics, and other low-wage sectors, while paying exorbitant tuition fees that subsidize underfunded institutions. In this managed system of extraction, students are simultaneously framed as a strain on public resources and quietly relied upon to sustain both the labour market and the post-secondary education system.

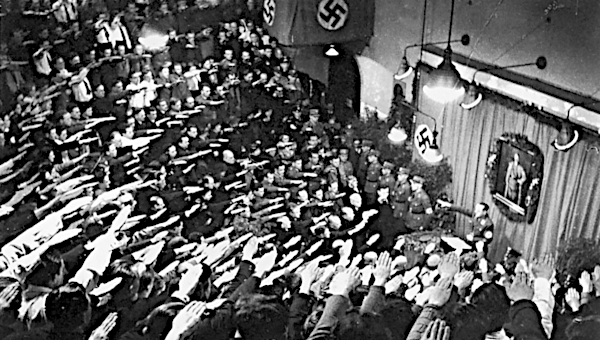

Alarmingly, South Asian international students are also being used as a rallying issue for recruitment and organizing by the far-right in Canada. A rising coalition of white supremacist Canadian groups known as Diagolon launched a hate campaign targeting Indian students. Between 2023 and 2024, right-wing social media platforms such as 4chan, Gab, and Rumble (a video platform that officially hosted the Republican primary debates) saw increases of 122, 251, and 6,300 percent respectively in hate speech targeting Indians. Jeremy Mackenzie, founder of Diagolon, frequently tells his followers that Indians will “take over Canada,” invoking what is known as Great Replacement Theory and using phrases such as “Canindia” and “Canada is no more,” claiming that “Indian criminals” are replacing white Canadians.

In response, liberal and progressive discourses have pointed out the fallacy of these claims and emphasized the contributions international students make to the Canadian economy. In 2022, international students contributed approximately $37.3 billion through tuition, housing, and other expenses. International students pay more than five times the tuition of domestic students and have helped offset provincial funding cuts to education. During the pandemic, restrictions on the number of hours international students could work, typically capped at 20 hours per week, were lifted, and these students were encouraged to serve as essential labourers, while Canadians were asked to stay home. There is a distinct and convenient collective amnesia at play in the public discourse that moved from praising international students as frontline workers during the pandemic to positing them as “job stealers.”

Progressive discourse has also focused on a new wave of racial tensions and harassment on university campuses. What does it mean to think about the “international student crisis” from the left? First, a transnational and transhistorical perspective on student migration has been largely absent. Second, labour has often been treated as secondary to immigration and racial equity, rather than as integral to both. Thinking of this crisis from the left means moving away from treating international students’ precarity as a novel and isolated phenomenon, and instead, situating the current crisis within the longer history of the global circuit of capital, labour, and migration. It also demands centring labour as a constitutive site of struggle, one through which immigration regimes and racial hierarchies are actively produced and contested, not merely intersected.

A Brief History of Migration Politics and the Indian Subcontinent

Understanding the current international student crisis requires tracing the different phases of migration from the Indian subcontinent and the class dynamics that have shaped diaspora formations. Unlike large-scale migration from India to the United States, which has often comprised the socially and economically privileged, Canada’s South Asian diaspora is older and deeply entwined with histories of colonialism and indentureship. This also includes migrations of people of Indian descent from British colonies such as Kenya, Guyana, and Trinidad and Tobago.

In Canada, South Asians, primarily Sikhs, arrived in the early 20th century as British subjects and faced numerous colonial immigration policies, including the disenfranchisement of natives of India not of Anglo-Saxon parentage in 1907, and the “Continuous Journey” regulation of 1908. In the 1960s, racial criteria in the Immigration Act were removed to meet economic demands, enabling the migration of skilled professionals who benefited from a new points-based system centred on occupation, skills, health, and language.

Nonetheless, during what is known as the “long 60s” of leftist political movements – that is, from the rise of Third Worldism at the Bandung Conference in 1955, through the end of the Vietnam War in 1975, to the death of Mao Zedong in 1976 – there was a distinct class consciousness among South Asian migrants and a desire for cross-racial class solidarities, especially among Punjabi farm workers. First-generation Punjabi workers drew clear connections between class struggles in South Asia and their new workplaces and social contexts. The East Indian Defence Committee, founded in 1973 to counter increasing racist attacks on South Asian migrants in Vancouver and Toronto, emerged under Marxist leadership that openly criticized upper-class South Asian community leaders and highlighted the entanglements of racism, classism, and the settler nation. Similarly, South Asian workers participated in the Afro-Asian Latin American Solidarity Committee in Montréal. While the diaspora was heterogeneous in language, class, caste, and migration pathways, migrants from the Indian subcontinent forged strong connections to global class struggles.

Beginning in the 1980s, with Canada’s neoliberalization, there was a shift in migration patterns from India. Canada increasingly attracted relatively wealthy immigrants from the Indian subcontinent until the late 2010s, with the exception of Tamil refugees from Sri Lanka. This period also marked the emergence of international students as a distinct migrant category. From the early 1980s, Canada implemented differential tuition fees for international students, attracting primarily wealthy students and reshaping public perception of international students as affluent foreigners rather than as beneficiaries of foreign aid. In the 1990s and 2000s, post-secondary institutions aggressively recruited international students. A 2012 national report declared international education is “a more valuable export than unwrought aluminum or helicopters and airplanes.” Canada’s 2014 strategy called for institutions to double the number of international students by 2022, reaching over 450,000. During this period, there was also large-scale migration of tech workers from India. More than 80,000 tech jobs were created in the Toronto-Waterloo corridor, which was said to be more than in San Francisco, Seattle, and Washington, DC combined.

Over the past decade, however, migration patterns have shifted again. Since the late 2010s, rising unemployment, the persecution of minorities, the drug epidemic in parts of India, and geopolitical unrest across Nepal, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka have contributed to new waves of migration from more diverse economic backgrounds. In the last few years, new private and often fraudulent post-secondary institutions have emerged, attracting many students from working-class and rural backgrounds who have sold land and other family assets to migrate in search of a better life. There has since been a crackdown on these institutions, leading to closures that have left students stranded and with little recourse for justice.

According to a 2024 CBC report, funeral workers at the Lotus Funeral and Cremation Centre in Etobicoke raised the alarm about rising suicide rates among recent migrants from the Indian subcontinent. The fact that the funeral home repatriates the remains of five to seven student workers every month attests to an epidemic that is largely ignored by both society and the state, and to the unbearable financial and social pressures these workers face. This new working-class migrant group forms part of a global proletariat and offers new ways of thinking about left politics.

Labour and ‘International Students’

International students now constitute a significant segment of Canada’s cheap labour force. From gig work and Amazon warehouses to factories and fast-food restaurants, they are often willing or compelled to work for less than minimum wage. These labourers are intentionally deskilled to remain disposable. Amazon, for example, uses algorithms to organize and manage labour processes, breaking work into simplified and standardized tasks that render workers easily replaceable. Gig work, such as Uber Eats delivery, offers a false promise of flexibility that appears suitable for students; yet most work 10-12 hours a day to make a living, waiting in the busiest parts of the city for their next order on the app and being paid only when they are actively delivering food. They are pitted against one another, constantly competing through algorithmic management while accepting wages below the legal minimum.

There is an urgent need to apply critical pressure to the category of “international students” from a labour perspective. The student designation allows both the public and workers themselves to frame exploitation as a temporary and expected phase of youth. In reality, these workers include graduates, those who are forced to discontinue their education due to financial hardship, and refugees working full-time as cheap labourers. In Toronto’s downtown core, for example, Uber Eats delivery workers range in age from their late-twenties to late-forties. The association of precarious immigration status with the economic, psychological, and social conditions implied by the category of “student” produces a highly exploitable labour subject. The focus on their status as students positions them as a special case and thereby further obscures their role in the nexus of capitalist labour.

Upon closer examination, what is often described in this manufactured common-sense narrative as “unchecked” large-scale immigration appears aligned with the provision of crucial material resources to national and capitalist interests. As economic and political tides continue to shift, these recent student migrants have borne the brunt of anger, including from other working-class communities and from established South Asian diasporas. Rather than simply lamenting the crackdown on students, this moment presents new possibilities for organizing and cross-racial working-class solidarities.

Centring the class position of international students, rather than their student status, places them in a longer historical arc of migrant labour, allowing paths to be forged alongside racialized and non-racialized workers. As transient gig work and transnational capital jostle for cheaper labour and more precarious conditions, this opens new avenues of struggle that do not rely solely on the exceptional circumstances of college shutdowns or shifting immigration rules. Critically, this rethinking allows for what is inevitably needed to confront the ever-expanding corporate hegemony and austerity agendas: the reimagining of labour struggles and the building of collective working-class organizing. •

This article first published on the Canadian Dimension website.