Capitalism, Colonialism, Canada: How the Past is Before Us

On January 13, Bryan D. Palmer, one of Canada’s most celebrated labour historians, will be giving the inaugural lecture at the opening of the Leo Panitch School for Socialist Education. In this essay, Palmer introduces the themes he will be elaborating in his talk.

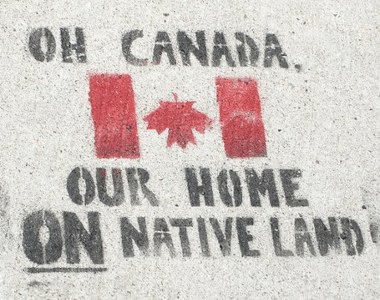

Capitalism and colonialism are the undeniable foundations of modern Canada. As reciprocal systems of appropriation and accumulation, they combined to produce the hegemonic hold of an ethos of possessive, acquisitive individualism, structuring economic development, state formation, and the social relations of everyday life.

In focusing on capitalist development and colonization as it relates to indigenous peoples, dispossession, and coercive assimilation, the central political question is when and how did struggles that linked class-based, potentially anti-capitalist, mobilizations mesh with anti-colonial indigenous movements? Such combined challenges to capitalism and colonialism have been rare, but are very much on the political agenda of our current conjuncture.

The capitalism/colonialism coupling struck blow after blow at indigenous sensibilities associated with what has been called the dish with one spoon, a generalized set of beliefs that, however differentiated across the diversity of indigenous political economies and the ecologies that so influenced them, underscored a communal as opposed to privatized societal organization.

Primitive Communism

Indigenous peoples operated, as Lewis Henry Morgan noted in the mid-19th century, in fundamentally different ways than those associated with the profit system of mercantile and then industrial capital. For First Nations, the public domain constituted what Morgan, and Karl Marx, designated a “primitive communism,” in which practices of hospitality were generally present. This was recognized by European interlopers and colonizers, who early on concluded that indigenous peoples of the North American continent, unlike themselves, “held all things in common.” Among these “things,” land was of course central, a material foundation on which collective relations and understandings of shared, egalitarian, relations might develop.

Introduced to the Parisian French Court and urban life in an Empire’s metropole in 1649, two “Savage Indians” were shocked that grown men would prostrate themselves before a child King, Louis XIV. They were aghast that the city exhibited such disarmingly contrasting displays of wealth and poverty, since, in their “primitive” understandings all were “equaliz’d in the balance of Nature, and not one to be exalted above another.” When these observations were reported in England, an editor denounced the indigenous men as “two Heathen Levellers.” Capitalism/colonialism versus the commons counter-posed material orderings of everyday life.

To explore the inseparable nature of capitalism and colonialism in the making of modern Canada, it is necessary to historicize the development of these twinned systems of accumulation. The following periodization is indicative of discernible trends. The 1500-1790 years were ones of capital cravings and the coming of colonialism. The next 100 years, 1790-1890, witnessed capitalism’s consolidation, the founding of the Canadian nation state, and a tightening of colonial constrictions on indigenous peoples. These processes accelerated and intensified over the course of 1890-1960, as modern, capitalist Canada took shape and the last regional outpost, the North, was colonized. And, finally the last 60 years or so commenced with the first sustained attempts to fuse anti-colonialist and anti-capitalist struggles in the New Left, only to see that climacteric shattered with the neoliberal assault on trade unionism and the evisceration of the left, leaving indigenous peoples to continue to wage struggles against capitalist colonialism into the 21st century.

From Colony to Nation

The century that reached from 1790-1890 witnessed the transformation of British North America, a patchwork quilt of colonial outposts, into a Confederated Canada that was a capitalist nation state. What is often lost sight of in the march from colony to nation, and the creation of a much-heralded “peaceable kingdom,” is the extent to which this process unfolded through often bloody confrontation. Capitalist and colonial imperatives were sandwiched between moments of rebellious resistance in the 1830s in Upper and Lower Canada and the first 1869-1870 stand of Riel and his Métis followers. Both armed uprisings failed, but they were not without momentous consequences. The former birthed responsible government and charted the path to a more democratic order. The latter instituted a Métis provisional government headed by Riel and was critical to bringing the West into Canada. Ironically, the Riel rebellion was committed to wresting the freedoms of the capitalist marketplace from the infringements on free trade of the infant state’s surrogate, the feudal monopoly of the Hudson’s Bay Company, and insisting on the rights of the original founders of Red River to a say in their governance.

The capitalist/colonizing project of the 19th century would be characterized by a relentless assault on indigeneity. Liberated from the unequal exchange of Empire-First Nations relations and mercantile capital’s reliance on indigenous peoples to harvest pelts, the consolidating capitalist order could materially move, not only to dispossess indigenous peoples of lands, but to tighten the noose of cultural denigration and further structure First Nations as wards of the capitalist colonial state, an agent of supposed civilizing betterment. Legislation such as the Gradual Civilization Act (1857) and the Indian Act (1876) did just this, bookending the British North America Act (1867) and sanctifying Confederation. The 1857 enactment set out the terms on which a century and more of state policy toward indigenous peoples would rest. It proclaimed the desirability of removing all legal distinctions between indigenous peoples “and Her Majesty’s other Canadian subjects,” insisting that the deserving path to aboriginal citizenship necessarily ran through the individual acquisition of property and the renunciation of “Indian” status, identity, and ties to traditional, collectively-occupied, lands. Involvement in the Canadian body politic, through voting, was deemed denial of indigenous being. Any “Indian so declared to be enfranchised … shall no longer be deemed an Indian.”

None of this happened without conflict. Prime Minister John A. Macdonald wrote in the mid-1880s to a future Minister of Finance and Receiver General and provincial premier, Charles Tupper, that the governing Conservatives were not in a “flourishing state.” He cited “Riel, the Knights of Labor, Home Rule, and the Scott Act” as serious challenges. If the emerging class conflict of these years harboured socialist intellectuals and critics of capitalism, fomenting strikes and mobilizing political campaigns in ways unprecedented in previous decades, the Métis-led war of resistance in the Canadian west culminated in an armed, anti-colonial uprising. There were suggestive links between the two main currents of opposition in the mid-1880s, but they were fragmentary and fleeting. The simultaneous sidetracking and defeat of workers’ and indigenous/Métis rebels indicated a fundamental divide. Workers were drawn into accommodations of the state, left internationally divided amidst splits and differentiated strategic directions, quieted by economic depression in the 1890s. Riel and his army of redressers, force on to their insurrectionary stand, were militarily vanquished, their retreat mandated by the superior forces and technologies at the disposal of the capitalist state, not the least of which was a transcontinental railway. This state had come a long way in enhancing its power since 1869-1870.

A class mobilization struggling to find its anti-capitalist voice and an anti-colonial uprising unsure of how to confront an increasingly entrenched state both went down to what might be considered defeats. These 1880s uprisings were overdetermined, in part, by their limitations, one measure of which was their separation from one another. The difficulty we have, a century and more later, in grasping what was missed in this road of common struggle not taken is itself a reflection of what was repressed and lost, as well as what has been validated and vindicated, in the promise, possibility, and passing of 1885-1886.

Over the course of the 20th century, the state and capital shifted their approach to indigenous peoples from one of generalized “contention to negotiation and enterprise,” especially in the post-1960s years. That tumultuous decade ended, not only with the October Crisis in Quebec, but with a successful Red Power repudiation of the state’s policy of coercive assimilation, epitomized in the White Paper call of Pierre Elliott Trudeau and Jean Chretien to jettison the Indian act and forever bury indigeneity and its claim to unique status within Confederation. Not unlike the response of the state and capital to World War II and post-war labour militancy, Canada’s ruling class and its apparatus of governance reoriented their approach to challenges waged against their power, opting less for the stick of coercion and more for the carrot of enticement.

Into the 21st Century and Idle No More

By the 1980s and 1990s and into the 21st century, there were nevertheless occasions – such as Oka, Ipperwash, Gustafsen Lake, and Elsipogtog – when First Nations-led confrontations took nasty, repressive turns: for each indigenous band placated and co-opted, there would be another alienated, drawing the short reconciliation straw. The militancy of Red Power, born of 1960s radicalizations, nonetheless managed to still resonate in indigenous stands. The oppositional forces behind such campaigns and conflicts, like the wildcat strikes of the mid-1960s, necessarily battled on many fronts, challenging capital, the state, and the bureaucracies and institutions within the indigenous political mainstream that benefitted from state largesse and bought into the politics of recognition and the rhetoric of reconciliation. A militant minority of indigenous activists occupied the same precarious terrain that a militant minority of the working class once inhabited.

Indigenous peoples had sufficient fight in them to launch Idle No More in 2012, a mobilization that, like the rejection of the state’s White Paper in 1969, was precipitated by a refusal to accept federal government legislation, the Jobs and Growth Act. This bill, an invasive reconstruction of 60 previously passed acts, threatened to undermine treaty rights ensconced in the Indian Act and weakened significantly a number of environmental laws that curbed the twinned capitalist and colonial for-profit exploitation of land, resources, and waterways. Mushrooming throughout Canada and the world, Idle No More proclaimed, as had Red Power in the 1960s, that a pan-Indian movement of resistance could indeed step outside of the boundaries of indigenous-state relations, however conciliatory they may have appeared in 21st-century Canada.

Without a re-envisioning of the revolutionary purpose that has historically, albeit all too rarely, surfaced in indigenous and non-indigenous alliance around intransigent opposition to the inseparably entwined structures of capitalist and colonial subordination, the opponents of these systems of debasement will remain divided and, consequently, enfeebled in their resistance, limited in the transformative possibilities they must, together, bring into being. If centuries of history from 1500 to the present indicate how daunting is the task before those who recognize the dire necessity of this anti-capitalist, anti-colonial politics, the current moment is one that cries out for the realization of what has so often seemed unattainable. •